The shores of Lake Arlington aren’t all that picturesque, especially on the Fort Worth side, where the rocky shoreline borders a massive parking lot and the summer sun reflects off both, making people feel like they’re inside a microwave oven. A stray dog nosing about in trash on the beach completes the postcard.

But on this particularly hot day, the 40 or so men gathered by the lake for barbecue apparently felt they’d found some inspiring scenery after all. Holding beers, 40-oz malt liquors, and food, they cheered and whistled for the two swimsuit-clad women strutting their stuff on a nearby dock.

But on this particularly hot day, the 40 or so men gathered by the lake for barbecue apparently felt they’d found some inspiring scenery after all. Holding beers, 40-oz malt liquors, and food, they cheered and whistled for the two swimsuit-clad women strutting their stuff on a nearby dock.

Doing their best to block out the catcalls, models Ryan “Pumpkin” Youtsey and Miss Joa posed for a magazine shoot. A young, laughing couple, the man in a white hat cocked just left of center, looked on, while a professional-looking 30-ish woman offered advice to the photographer and stepped in occasionally to pour more bottled water on the models’ chests.

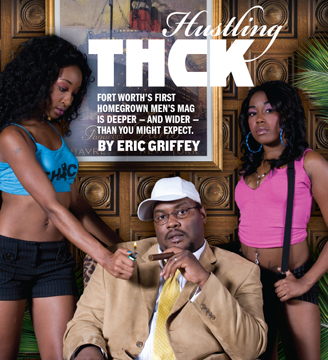

Magazine publisher and co-founder Claudia Davis DaRobi was tossing the water. The man in the hat was Mason Flint, 28, the large, energetic, and good-humored co-founder of the magazine in question. “Don’t smile,” he told the models in mock sternness. “I hate smiling.” The shoot was for THCK Reloaded – pronounced “thick,” with the silhouette of a zaftig woman standing in for the “I.” The initials stand for “True Hustlers and Corporate Kings,” and it’s Fort Worth’s first men’s magazine.

If the name, the gritty scene, and the shape of the silhouette seem odd for a men’s magazine, you’re getting the right picture. THCK specializes in dichotomy. Trust Cowtown to birth what is surely the first men’s magazine in the country where the publisher doesn’t like too much cheesecake, and the text is all about people who’ve made it from the wrong side of the tracks to the side of the “corporate kings.” Think hip-hop meets Fortune meets Hustler meets Big is Beautiful. And you’ve got THCK, a publication that’s hot on the local party scene and gaining a national reputation as well – while depending on back-of-the truck distribution.

The magazine, now in its second year, profiles people who have turned away from a life of “hustling,” which could mean drug sales, gang life, or any number of illicit lifestyles, to use those street skills instead in legitimate entrepreneurial pursuits. In the accompanying photos, the “corporate kings” are draped with models whom, in DaRobi’s words, she’s “pulled off the pole” of topless clubs – women who are a lot curvier than any model you’ll find in a Victoria’s Secret catalog. “We don’t have size 0-4 models in our magazine,” said Flint.

DaRobi said the models themselves in some cases have become advertisements for the magazine’s message, using their photos in THCK as a starting point for modeling careers, rather than going back to dance in the clubs again. THCK’s print distribution is about 10,000, but the magazine’s web site has had well over one million hits. Flint and DaRobi do the lion’s share of the writing, design, marketing, and most other jobs of a small startup publication. And thus far, it’s a labor of love. The pair do all the distribution, driving from city to city, club to club, party to party, passing out the magazines and their promotional DVD, featuring the girls partying with rappers and various hustling/corporate king-types.

In Fort Worth, THCK is becoming synonymous with turning the party out. The magazine recently hosted promotional events at two local clubs. They bring a small army of women who pass out the DVDs, show their talents on the dance floor, and clink a champagne flute or two in the VIP lounge. Inside its glossy pages, however, THCK is more than just scantily clad women and reformed criminals. It also covers business news, social issues, and the rap scene. Some of the content is Fort Worth-oriented, such as the stories on local rappers, but much more of it is aimed at a national audience. An upcoming issue, for instance, will deal with the theme of war: the war in Iraq, the war on drugs, gang wars, etc. Beneath its veneer of hip-hop braggadocio, Flint and DaRobi say, their magazine is all about making a positive impact in the community. They see it as a guide for men who are looking to escape the “trap,” a term used to describe boarded-up, abandoned buildings used as drug houses, where people end up trapped inside.

Other issues have told the stories of men like Rodney Brown, who used to distribute cocaine and heroin in Fort Worth but turned his life around while in prison. Flint and DaRobi say they hope such articles will inspire other people stuck in the “trap” – and just to make sure those people will read the stories, they position women in bathing suits all over their pages. As DaRobi explains, young urban men are more likely to read about hustlers who have turned their lives around if there are half-naked women on the cover. “We give you what you want to see, but you will see what we have to say,” said DaRobi, who was dressed in a business suit and talks quickly, with a polished PR/marketing vernacular: “I’m a conservative woman, but in order to get the attention of our target readers, the guy that is stuck in the trap right now, we have to have a beautiful woman with a size 40 waist telling you to how to transition from the trap to the world. They’re going to listen.”

The bi-monthly mag is separated into four major sections. “From the Trap to the Boardroom” features the people who have made that transition. “Street Heat” reports on up-and-coming musicians, rappers, and bands, and there are also sections on entertainment and technology.

The magazine operates on ad revenue alone. It’s distributed for free – for now. And while it isn’t necessarily aimed solely at African-Americans, most of the featured business owners, rappers, and models are black, and issue stories lean heavily toward concerns of the black community.

THCK’s message-driven thong-a-thon is a part of a growing trend in the hip-hop culture, of young streetwise types starting their own businesses. The trap-to-the-boardroom motif particularly resonates with rappers. Rapper Jay-Z, a former drug dealer, is CEO and owner of a major record label, has his own brand of vodka and clothing, started the 40/40 Club restaurant/lounge, and owns part of the New Jersey Nets basketball team. Rapper and former gang member 50 Cent invested in a company called Glaceau, which distributes vitamin drinks and was just sold to Coca-Cola for $4.1 billion. Flint and DaRobi want to capitalize on that current fashion for entrepreneurship.

For Flint, though, that move up from illicit to legit isn’t just a fad. It’s a key part of his life story.

For Flint, though, that move up from illicit to legit isn’t just a fad. It’s a key part of his life story.

“The magazine is Mason,” said DaRobi. “He’s a hustler and grinder from the trap.”

When Flint, a Lubbock native, moved to Weatherford in eighth grade, he found himself one of the few black students in an almost all-white town, but readily accepted because of his basketball prowess. “I thought, ‘I’m going to school with all these white people,'” he said. “But I was accepted. With playing basketball, it was the ultimate front. Nobody ever knew that I sold drugs.”

He said he sold cocaine and marijuana to his “preppy” white friends and estimates that he was making about $5,000 a month at age 19. He also enjoyed going to all the parties and being “that guy” who could get drugs. He was never arrested and never spent any time in jail but still was no stranger to the trap – he regularly traveled to Fort Worth to pick up product in just such houses.

But Flint said he decided after high school that the drug-dealing life wasn’t for him. He didn’t have any big life-changing moment or realization – just kind of outgrew the lifestyle. He went to Remington College in Fort Worth and, during his time there, applied for an internship with the company that published the Diversity Directory: the Fort Worth Area Black Pages, a guide to black-owned businesses.

That magazine’s founder and publisher was DaRobi, a Georgia native who grew up in Fort Worth near Polytechnic High School. She graduated from Paul Quinn College in Dallas with a degree in marketing and set out to realize her childhood dream of being a magazine publisher. She has worked for several local publishing companies, including Thompson Publishing Group and Knowles, a publisher of law textbooks. She took a chance on Flint because she was a friend of his sister. A few years older than Flint, she admits to being a micro-manager. She had no idea what a trap house was, let alone that her new intern had done business in one.

“The thing that got me is that Mason was the first person in his family to graduate college,” said DaRobi.

She encouraged Flint to think about what kind of magazine he would want to start. His answer was simple: He wanted a booty magazine. DaRobi and Flint decided to collaborate. What they came up with is a magazine that would combine the social conscience of the Diversity Directory with Flint’s vision of mostly naked butts. “I can’t lie to you – when we first started THCK, I was thinking booty, booty, booty, women, booty,” said Flint. “But what she did is, she morphed it into what it is today.”

Flint and DaRobi said that they frequently knock heads over the half-naked women all over the magazine, but agree that the two elements are compatible. DaRobi has to “pull Mason back,” when the photo shoots get too racy. “As black males, we have to be drawn in by something,” said Flint, referring to the THCK models. “You can’t just say ‘Hey, here’s a magazine about business,’ unless you’re in business. The people we profile are different. It’s people who have been in the pen for 15 years and then come out and want to change their lives. We profile women who are different, too.”

Flint and DaRobi said that they frequently knock heads over the half-naked women all over the magazine, but agree that the two elements are compatible. DaRobi has to “pull Mason back,” when the photo shoots get too racy. “As black males, we have to be drawn in by something,” said Flint, referring to the THCK models. “You can’t just say ‘Hey, here’s a magazine about business,’ unless you’re in business. The people we profile are different. It’s people who have been in the pen for 15 years and then come out and want to change their lives. We profile women who are different, too.”

For the first few months, the two operated the magazine out of their living rooms and traded small percentages of ownership in the company for photography work, design help, and all of the other technical aspects of the magazine. The seed money of $15,000 came from their own pockets.

The next step was finding the models. When DaRobi says that she has pulled women “off the pole,” she’s not exaggerating by much. She is banned from a couple of area strip clubs for recruiting their dancers.

Some of the ex-dancers have revived their modeling careers with the help of their work at THCK. “Pumpkin” Youtsey, for instance, had been trying to make it by herself in the modeling world but fell into a job as a stripper. Seduced by the late-night party lifestyle that goes with being an exotic dancer, she developed a drinking problem. She said that the difference between stripping and nearly nude modeling is more than just a few pieces of clothing. “They kind of pulled me away from dancing,” she said. “I don’t have to dance anymore. They got me a lot of modeling exposure, they’ve set up photo shoots for me, and video shoots. They’ve put me in the business.”

When she was a dancer, she said, her life was all-night parties and binge drinking. Now she is pursuing her modeling career full-time and hopes to one day be featured in Playboy. In the meantime, she intends to keep working as a THCK model.

During the six years he spent in a federal prison for selling drugs, Rodney Brown decided to make some changes in his life. He said he’d been making more than $10,000 a day selling cocaine and other drugs – but paid a high price in constant fear. He realized that, with help from God, he could apply the same skill set that made him such a successful drug dealer to building a legitimate business – and a feeling of safety. “When I hustled and sold drugs, I was literally scared every day,” he said. “Whether it was the woman I was lying next to or the man I considered to be my right-hand man, they could come in and kill you and take everything you have or set you up. They know when you’re getting your supply, they know when you are going to have a lump sum of money, they have the upper hand. In the streets there are no rules; there are no ethics and codes.”

During the six years he spent in a federal prison for selling drugs, Rodney Brown decided to make some changes in his life. He said he’d been making more than $10,000 a day selling cocaine and other drugs – but paid a high price in constant fear. He realized that, with help from God, he could apply the same skill set that made him such a successful drug dealer to building a legitimate business – and a feeling of safety. “When I hustled and sold drugs, I was literally scared every day,” he said. “Whether it was the woman I was lying next to or the man I considered to be my right-hand man, they could come in and kill you and take everything you have or set you up. They know when you’re getting your supply, they know when you are going to have a lump sum of money, they have the upper hand. In the streets there are no rules; there are no ethics and codes.”

Brown said that he was on the run so much that he never really had time to think about whether he liked the life he was leading. Prison offered him an opportunity to decide where he wanted his life to go when he got out, and it gave him a chance to get right with God, just as he had been as a child. “When I was incarcerated, I had a chance to analyze things in my life, and I began to realize that before I could have a relationship with God, I had to start practicing self-discipline,” he said. “I had to start saying ‘No, I’m not going to do this.’ ” Brown, who had done some construction work before prison, earned an associate degree behind bars. After his release, he said, he received a $30,000 inheritance and used it to go into business for himself, remodeling and refurbishing homes. To earn extra money, he worked for Nick Zeigler, a local construction contractor.

After only a few months, Zeigler was sufficiently impressed with Brown to make him his business partner. Eventually, Brown went back out on his own, using a $300,000 loan from Zeigler to start his own construction business. His company, R. Brown Construction, has grossed well over $11 million over the last two years, he said, giving him a legitimate claim to the “corporate king” title.

After only a few months, Zeigler was sufficiently impressed with Brown to make him his business partner. Eventually, Brown went back out on his own, using a $300,000 loan from Zeigler to start his own construction business. His company, R. Brown Construction, has grossed well over $11 million over the last two years, he said, giving him a legitimate claim to the “corporate king” title.

His success and dramatic turnaround made him the archetypal subject for THCK and the subject of their first cover. On the magazine’s DVD, Brown is portrayed as the ultimate example of how to go “from the trap to the boardroom.” Brown believes that a publication like THCK, appealing to urban youth, is long overdue. “That magazine means something,” he said. “They’ve got something good that is going to benefit others in the community.”

In the tradition of underground hip-hop, THCK has adopted the proverbial back-of-the-truck style of distribution. But their truck gets around. DaRobi and Flint realized that, though Fort Worth was their home, they needed to reach a national audience. The promotional version of THCK featured Miami hip-hop hustler turned corporate king, Rick Ross, so they wanted to throw a launch party in Miami. With a little financial help from a friend of DaRobi, the two grabbed a stack of their newly minted magazines and headed down to Florida. They both said they were so broke that they went three days without food just to promote THCK in that city. But they did have a budget for throwing a massive party that was attended by such hip-hop royalty as Ross, Trick Daddy, and Flavor Flav.

News of their party and magazine spread quickly throughout the Florida hotspot, so much so that during a stroll down South Beach, another hip-hop legend introduced himself to the pair in an unusual way, DaRobi said. “We were in Miami in South Beach, walking down the beach, and this red Avalanche with suicide doors [opening away from each other] pulls up, and they said ‘THCK Magazine?’ and Birdman and his people jumped out of the car and asked to have their picture taken with us,” said DaRobi. “I said that’s our role – we’re supposed to be getting our picture taken with you.”

They have taken their proverbial truck to other cities such as Dallas, Houston, and Denver to pass out the magazine, to party, and to extend their reach. “As long as we centered our business [just] in the city of Fort Worth, we struggled,” said DaRobi. “I wanted to make sure that it was based in Fort Worth because I am from Fort Worth.” Now with a few advertisers signed up, they have a little money trickling in, but most of their out-of-town promoting excursions are still paid for out of their own pockets. Locally, their messages of success and social justice seemingly haven’t reached very far yet. Members of the local Black Chamber of Commerce and other community leaders hadn’t heard of the magazine.

They have taken their proverbial truck to other cities such as Dallas, Houston, and Denver to pass out the magazine, to party, and to extend their reach. “As long as we centered our business [just] in the city of Fort Worth, we struggled,” said DaRobi. “I wanted to make sure that it was based in Fort Worth because I am from Fort Worth.” Now with a few advertisers signed up, they have a little money trickling in, but most of their out-of-town promoting excursions are still paid for out of their own pockets. Locally, their messages of success and social justice seemingly haven’t reached very far yet. Members of the local Black Chamber of Commerce and other community leaders hadn’t heard of the magazine.

However, in the club scene, THCK is at least on the radar. William Powell, owner of the Aqua Lounge in downtown, said that he has heard of THCK, though he hasn’t seen it yet. As an owner of a club that books hip-hop acts, he welcomes any magazine that promotes them. Matt Sonzala, a prominent blogger and music journalist who now lives in Austin, said he hadn’t seen THCK but thought the concept could work – though it’s a chancy field. “I see a lot of those magazines, and most of them don’t last very long,” he said. “They aren’t very high quality, and there’s not much to read about, and quite often they do fall back on scantily clad women.” The trick to staying in business, he said, is distribution and backing.

The two founders predicted that in a year’s time, their print circulation will be five times what it is now. They are working on a deal to get THCK distributed in area 7-Elevens. In Fort Worth, the THCK machine is constantly on the move. DaRobi and Flint hosted a “corporate kings night” at Bent Lounge in downtown Fort Worth, and recently hosted an event at Club Axis that is still raging on in the imaginations of those who attended. During a trip to a local barbershop, DaRobi realized that THCK’s reputation had begun to grow.

“This one barber in there asked if it was the ‘real’ THCK magazine or just some local version,” said DaRobi. “It was good when he realized that I wasn’t just the marketing rep. It’s funny because your reputation can outgrow who you actually are.”