Nestled behind a row of trees across from the TCU soccer fields on Bellaire Drive South is a quaint limestone building with large wooden doors.

Compared to the university’s newly furnished athletic facilities and the swanky houses that cast their shadows on the rocky edifice of the structure, Trinity Episcopal Church seems an anachronism, harkening back to some pre-industrial village scene on a greeting card. Inside, the stone walls and high wooden ceilings crossed by beams are elegantly set off by striking renderings of biblical scenes on glass. Rows of wooden pews face the altar, which is wreathed in flowers and shimmering from the reflection of the lighted candles. Father Fred Barber’s white robes and metal-rimmed glasses give him a striking, somewhat erudite appearance. The message of his sermon this Sunday is how to live and share the gospel of Christ. His strong, kindly baritone reverberates off the walls and ceilings. “We do not pretend to know the mind of God,” he says. “On the one hand are Presbyterians who believe in predestination. On the other hand are the Baptists who believe in man’s free will. And then there is us, right in the middle. We just don’t know.”

Compared to the university’s newly furnished athletic facilities and the swanky houses that cast their shadows on the rocky edifice of the structure, Trinity Episcopal Church seems an anachronism, harkening back to some pre-industrial village scene on a greeting card. Inside, the stone walls and high wooden ceilings crossed by beams are elegantly set off by striking renderings of biblical scenes on glass. Rows of wooden pews face the altar, which is wreathed in flowers and shimmering from the reflection of the lighted candles. Father Fred Barber’s white robes and metal-rimmed glasses give him a striking, somewhat erudite appearance. The message of his sermon this Sunday is how to live and share the gospel of Christ. His strong, kindly baritone reverberates off the walls and ceilings. “We do not pretend to know the mind of God,” he says. “On the one hand are Presbyterians who believe in predestination. On the other hand are the Baptists who believe in man’s free will. And then there is us, right in the middle. We just don’t know.”

The ritual solemnity of the service unites the parishioners as they pray and take communion together. Bells chime. The congregation makes its spoken responses in the words of the Book of Common Prayer. To the uninitiated, this Holy Communion service at Trinity Episcopal Church calls to mind the pageantry of centuries ago. But this rich tapestry, threaded with strong strands of tolerance and freedom from clearly defined dogma, is threatening to unravel. The American-based Episcopal Church and the worldwide Anglican Communion of which the church is a part are engaged in a bitter struggle over the roles of homosexuals and women within the church. This long-simmering disagreement broke out into open warfare in 2003 with the consecration of the openly gay V. Gene Robinson as the Bishop of New Hampshire. Since then, the events in this intense and increasingly less polite fight have often seemed more like something you might read while standing in the checkout line in the grocery store than in the annals of a denomination that intuitively searches for the “middle way.”

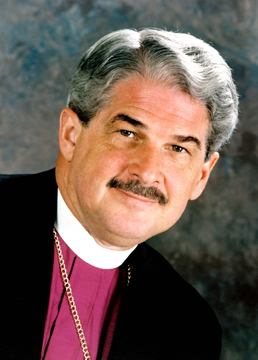

In North Texas, the drama is playing out in many sanctuaries, as divisions within the church threaten to shatter the brittle mosaic that is modern Anglicanism. In one Tarrant County church a few years ago, the pastor walked on the Episcopal Church flag. A vicar west of Fort Worth claimed — wrongly, as it turned out — that vandalism in his church was retaliation for his rejection of “biblical revisionists.” In the Episcopal Diocese of Dallas, a Plano church has left the Episcopal Church entirely. And Fort Worth’s bishop has declared that some actions of the national church are null and void in his diocese. Fort Worth has become a poster diocese for the issues that have plagued the whole church. There are no women or openly homosexual priests within the diocese as a result of the conservative leadership — some would say tyranny — of Bishop Jack Iker. A polarizing figure to Fort Worth Episcopalians, he has aligned himself with other dissidents within the church, steering the diocese toward a separation and legal battles over property rights. He’s also aligning the Fort Worth diocese, or at least some of its churches, with a portion of the worldwide church led by a gay-hating Nigerian cleric. Individual churches are already deciding whether to stay in the American church or possibly break away with Iker, if he tries to take the diocese out of the national church — a move that may be made as early as this fall.

Very few people in the area are willing to talk openly about the conflict for fear of retribution from Iker. His critics say that he has bullied and manipulated the laity and laws of the church to maintain a hold on his fiefdom. His supporters point to a number of panels and resolutions from the Anglican Communion that support his positions. They believe he is acting as a steward of the traditional teachings of the church. Countless individuals and groups are trying to hold the church together, including Via Media (Latin for “the middle way”), a national group made up of both laity and clergy. But despite those efforts, people from both ends of the theological spectrum are jumping ship, believing that the three-legged stool of Anglicanism — scripture, reason, and tradition — has been pulled out from under the congregations as their leaders, at home and abroad, pursue a feud that could split the church forever.

It’s perhaps ironic that questions of marriage and bed partners are what threaten, in the 21st century, to break apart the church known in this country as the Episcopal and in the rest of the world as Anglicanism. Because in the 16th century, it was another fight over marriage (and divorce) that led to the creation of the Anglican Church, founded on the very idea of compromise. England’s King Henry VIII wanted a divorce from his first, devoutly Catholic wife, Catherine of Aragon, who had failed to produce him a male heir. He couldn’t get a divorce from Pope Clement II, so he declared himself “Supreme Head in Earth of the Church of England.” Catherine did produce a daughter, however, and when Henry died, that daughter — known to history as “Bloody Mary” — brought back Catholicism to England with a vengeance, sending hundreds of non-believers to their deaths. A national crisis of faith fell to her half-sister and successor, Elizabeth I, a protestant. To stave off an impending civil war over religion, she accepted and enforced a blend of protestant beliefs and Catholic ways of worship, embodied in the Book of Common Prayer, which allowed for different interpretations of Christianity, held together by shared history. Anglicanism spread as the British built their empire, ending up in the United States as the Episcopal Church.

This time around, the fight is over gay priests and bishops, the sanctioning of gay unions, and the ordination of women. The elevation of Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori last year got conservatives riled up. But when the church’s governing body confirmed Robinson as the first openly gay Episcopal bishop, it sparked an uprising of conservative militants. On the one hand, the so-called “traditionalist”‘ elements of the church (its more conservative members) believe that the core tenants of Christianity have been betrayed and that the Episcopal Church of the United States of America, or ECUSA, has crossed over into an altogether different religion, ignoring orthodox biblical interpretation regarding the place of women in the church and homosexuality. Ever since then, a small but loud segment of conservatives has been calling to be governed by an alternate body — and an alarming number of conservatives have simply walked away altogether.

On the other side of the proverbial aisle are the majority of Episcopalians, who believe the ordination of a gay bishop is a culmination of centuries of progress, and the attempts of dissenters to circumnavigate the canonical or constitutional laws of the church amount to a rejection of its real traditions. The character of the church is historically diplomatic and inclusive, but the church is at an historic crossroads. A group of top officials in the Anglican Communion has set a Sept. 30 deadline for the ECUSA to change its ways on gays. Some of them lump together the elevations of both Jefferts Schori and Robinson as further proof of the moral decline and loss of orthodoxy in the church. The immediate controversy over Robinson has overshadowed the fact that a woman has risen to such prominence within the church.

![Reaves: ‘As soon as [conservative Episcopalians] can find a viable entity to be a part of, a formal split will take place.’](https://www.fwweekly.com/wp-content/images/stories/images/archive/2007-05-02/feature_pic2_5-2.jpg) Many others are taking advantage of this gathering storm to push their own agendas. A group of ultra-conservative bishops from what is called the Global South region of the international Anglican Communion is offering its own brand of orthodoxy as an alternative to the ECUSA. Several conservative groups and eccentric millionaires are using their hefty checkbooks to try to affect electoral politics in this country via the pulpit. Former UTA grad student Howard F. Ahmanson Jr. is one of a small but growing number of wealthy evangelicals working to blur the line between church and state. As part of that movement, they are funding conservative groups within the Anglican Communion in an attempt to destabilize the Episcopal Church and steer it further to the right — an ironic development, considering the church-state entanglements in Henry VIII’s time that led to murder and war — and to the “middle way” Anglicanism. The “big tent” character of Anglicanism has always been one of its more attractive features, especially for people marginalized by society — gays, women, minorities. But in Fort Worth, the leadership of the diocese is driving many of those people away.

Many others are taking advantage of this gathering storm to push their own agendas. A group of ultra-conservative bishops from what is called the Global South region of the international Anglican Communion is offering its own brand of orthodoxy as an alternative to the ECUSA. Several conservative groups and eccentric millionaires are using their hefty checkbooks to try to affect electoral politics in this country via the pulpit. Former UTA grad student Howard F. Ahmanson Jr. is one of a small but growing number of wealthy evangelicals working to blur the line between church and state. As part of that movement, they are funding conservative groups within the Anglican Communion in an attempt to destabilize the Episcopal Church and steer it further to the right — an ironic development, considering the church-state entanglements in Henry VIII’s time that led to murder and war — and to the “middle way” Anglicanism. The “big tent” character of Anglicanism has always been one of its more attractive features, especially for people marginalized by society — gays, women, minorities. But in Fort Worth, the leadership of the diocese is driving many of those people away.

According to Rev. Bill Nix, former rector at All Saints Episcopal Church in Fort Worth, the potential for separation from the church makes this a very tense time to be an Episcopalian in Fort Worth. “I think the lay people are the ones who are suffering over this,” he said. “I know plenty of people who are anxious about the situation because they are committed to the ECUSA and don’t want their diocese or their parishes to leave. They are living under a cloud.” One person driven away by the actions of the diocese is Trevor Gates, who moved from Virginia to Fort Worth in 2004 and stopped attending the Episcopal Church because of the diocese’s reaction to the consecration of a gay bishop. “I have been pretty turned off by the local diocese and don’t feel like it’s a place that is supportive of me as a gay man,” said Gates, who found the inclusive nature of the Episcopal Church in Virginia appealing. “Social justice and respect for the inherent dignity and worth of all people don’t seem to be a part of the equation in Fort Worth.”

He said that the local arm of Integrity, a group supportive of gays and lesbians within the church, has been sympathetic, and that if the diocese does break away, he would be willing to come back to the Episcopal Church. Iker first made rumblings about a split three years ago, when he stated that “if the Episcopal Church decides to walk away from the Anglican Communion, this diocese will not depart with them.” But he stopped just short of saying that he would be the one doing the leaving. The national church’s current official position on the ordination of homosexuals was established at the 1979 General Convention, where it was deemed “not appropriate.” The 1998 Lambeth Conference, a gathering of Anglican bishops from around the world that takes place every 10 years, passed a resolution saying that homosexuality was “incompatible with scripture.” Observers point out that the angry dissenting voices in the Anglican Communion have no real authority in the Episcopal Church. They also accuse Iker of bending church laws, mainly by using non-binding resolutions from outside of the ECUSA, as justification for some of his actions.

According to Rev. Nix, ignoring canonical law has been a pattern in this diocese. “Instead of citing the legally constituted authority of the Episcopal Church, which is the General Convention, they will pick resolutions with absolutely no authority.” Samuel Hudson, a ninth-generation Episcopalian who spent most of his life in Fort Worth, believes that some of Iker’s actions are an abuse of power. “Although Bishop Iker has been careful not to leave many fingerprints, there is more than enough documentary evidence of how he has transgressed church law and damaged innocent people to draw up what is called a ‘presentment,’ a list of charges that he will have to answer before an ecclesiastical court.” For many Fort Worth Episcopalians, the tension between this diocese and the ECUSA is nothing new. Katie Sherrod, a parishioner at Trinity Episcopal who is married to Episcopal priest Gayland Poole, believes that Iker is just picking up where his predecessors left off. “Ever since the diocese of Fort Worth was formed by splitting from the Diocese of Dallas, we have had very conservative bishops,” she said. “Jack Iker is continuing the tradition of being unhappy with the Episcopal Church. Every time we expand the group beyond the power of white males, there is a big uproar. Any challenge to the patriarchy is going to upset a lot of people.

“The struggle goes on daily, in many ways,” she continued. “At parish meetings, at adult forums, and at other gatherings in the parish, it has become clear that the parish wants to remain in the Episcopal Church, no matter what the bishop does.” In addition to her membership in organizations that promote women’s issues, Sherrod is also on the board of Claiming the Blessing, an organization of Episcopalians that promotes full inclusion of homosexuals in the church. In 2002, one of those organizations, the Episcopal Women’s Caucus, sent a female priest to work and live in Fort Worth. Rev. Barbara Schlachter of Ohio compared it to stepping back in time. “It was stressful,” she said. “I felt like I had gone back in time about 20 or 30 years. I was always aware of a lot of tension. I know that there were some people, clergy and laity, who became more aware of the politics within the diocese as a result of me being there.”

She said that overall her experience was positive and that she was well received. “There was a sense that it was important to have an ordained woman in that diocese for people who had not had a chance to participate in any kind of service with one. Some of the clergy were very warm, and some were stiff and rude.” One of the stiffer clergymen was Bishop Iker, who told her that she was not welcome and accused her of “meddling.” He also forbade her to stand at an altar when she did a Holy Communion service. Another soldier in the diocesan battle is George Komechak, president of the Fort Worth arm of Via Media. According to him, one of the difficulties in getting information to the laity is that members of the clergy don’t want to create rifts within their congregations. “The clergy doesn’t want to create a division within their parish,” he said. “They don’t want to see people line up on either side of an issue.” He said that the main function of Via Media is to increase awareness in the diocese. “A lot of people don’t want to get involved in church politics. They are putting their heads in the sand.”

Nationally, the battle lines were drawn even more sharply after the General Convention in 2003, when Bishop Bob Duncan of Pittsburgh called upon the Archbishop of Canterbury and the primates — the leaders of the church’s numerous provinces — to act against Robinson’s consecration. He also spearheaded a nationwide plan for “realignment,” the details of which were addressed in a letter by Rev. Geoff Chapman of Pittsburgh to potential supporters. “Our ultimate goal is a realignment of Anglicanism on North American soil committed to biblical faith values,” he writes. “They have just handed the gay lobby a stunning victory but are being forced to pay a fearsome price for it.” A month after condemning Robinson’s election at a meeting in Plano, Duncan helped create an organization called the Anglican Communion Network (ACN), with himself as its leader. The Network will “creatively redirect finances,” “refocus on Gospel initiatives,” and advocate “a faithful disobedience of canon law on a widespread level” if property disputes are not settled favorably. The Network’s ultimate aim is to supplant the jurisdiction of the ECUSA.

Nationally, the battle lines were drawn even more sharply after the General Convention in 2003, when Bishop Bob Duncan of Pittsburgh called upon the Archbishop of Canterbury and the primates — the leaders of the church’s numerous provinces — to act against Robinson’s consecration. He also spearheaded a nationwide plan for “realignment,” the details of which were addressed in a letter by Rev. Geoff Chapman of Pittsburgh to potential supporters. “Our ultimate goal is a realignment of Anglicanism on North American soil committed to biblical faith values,” he writes. “They have just handed the gay lobby a stunning victory but are being forced to pay a fearsome price for it.” A month after condemning Robinson’s election at a meeting in Plano, Duncan helped create an organization called the Anglican Communion Network (ACN), with himself as its leader. The Network will “creatively redirect finances,” “refocus on Gospel initiatives,” and advocate “a faithful disobedience of canon law on a widespread level” if property disputes are not settled favorably. The Network’s ultimate aim is to supplant the jurisdiction of the ECUSA.

Leaders of the dissident groups sought recognition by Anglican provinces in other parts of the world that were also unhappy with the direction of the Episcopal Church in this country and predisposed to undermine its authority. Ten out of the 111 dioceses in the United States joined the ACN, including Fort Worth. At the request of the primates, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, formed a commission in October 2003 to examine the crisis. The result of their inquiry, The Windsor Report, called on the Episcopal Church in the United States to stop consecrating gay bishops. The ECUSA apologized for the pain they had caused and declared a moratorium on consecrating all bishops, gay or otherwise. They did not, however, apologize for consecrating Robinson. In 2005, the Anglican primates, meeting in Ireland, in essence asked the Americans and the Anglican Church of Canada — which also endorses same-sex unions — to go to their rooms and think about what they’d done and attempted to assert authority over them. Several primates also refused to attend service with American Bishop Frank Griswold.

The American church responded in uncharacteristically strong language. At the meeting of Episcopal bishops in Navasota, Texas, later that year, Griswold, who presided, said that the primates were “out for blood.” He accused the Network of rebel dioceses of exerting influence over the proceedings in Ireland to meet their own ends. “The devil is a liar and the father of lies, and the devil was certainly moving about” at the meeting in Ireland, he said. In September of that year, Bishop Peter Akinola changed the Nigerian Church’s constitution to create an umbrella for rebellious American dioceses, “to give a worship refuge to thousands in the United States who no longer feel welcomed to worship in the liberal churches.” Several churches in Virginia accepted his offer. He further isolated the Global South by removing the name of the Archbishop of Canterbury from the constitution, because of the archbishop’s inclusive stance on homosexuality. Akinola also publicly supported a Nigerian law criminalizing same-sex marriage, denying homosexuals the freedom to assemble and petition their government, and allowing prosecution of newspapers and religious groups that support or publicize gay unions.

In 2006, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church passed a vague resolution urging church leaders to “exercise restraint by not consenting to the consecration” of bishops “whose manner of life represents a challenge to the church.” But, with polite apologies, the General Convention also rejected the idea of creating an alternative governing body to oversee those few parishes and diocese that could not accept the leadership of the ECUSA. To make matters even tenser, in the eyes of the ECUSA’s detractors, the 2006 convention also consecrated Jefferts Schori as the first woman to ascend to the role of presiding bishop. She made her support of gay unions well known, fueling the fire of schism. Her consecration also has fed the controversy surrounding the ordination of women, which some dioceses in the Network — like Fort Worth — and the Global South oppose.

Unhappy with the lack of a response from the Americans, a majority of Anglican Archbishops set the Sept. 30 deadline demanding that the U.S. Episcopal Church place a ban on the consecration of more openly gay bishops and on official prayers for same-sex couples. And they reiterated their appeal for the creation of alternate leadership for the Network and others who cannot accept Jefferts Schori’s leadership. But the American bishops were having none of it. At a conference last March, they again soundly rejected the archbishops’ demands. To set up such a system of alternate leadership, they write, would “replace the local governance of the church by its own people with the decisions of a group of distant and unaccountable prelates.” Such a scheme, they believe, “encourages one of the worst tendencies of our Western culture, which is to break relationships when we find them difficult instead of doing the hard work necessary to repair them.” The bishops also proclaimed that “gay and lesbian persons are full and equal participants in the life of Christ’s Church.”

It’s not just the so-called conservative elements of the church that want to sever ties. Last February, Bishop Steven Charleston, president of the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Mass., told the Washington Post that he would welcome a schism. “I would accept a schism,” he said. “I would be willing to accept being told I’m not in a communion with places like Nigeria if it meant I could continue being in a position of justice and morality. If the price I pay is that I’m not considered to be a part of a flawed communion, then so be it.” The local reaction to Robinson’s ordination mirrored the national one. Iker and others immediately denounced the consecration of a gay bishop, claiming that the church had abused its power. “These acts are thus held to be null and void, and of no effect in the Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth,” he said.

For many in the diocese, the General Convention was a call to action. In maybe the most belligerent protest, Father Deuel Smith, the rector of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church in North Richland Hills, threw the flag of the Episcopal Church on the floor in front of the altar and proceeded to walk back and forth over it throughout his sermon. He also put black tape over the word “Episcopal” on the church’s signs, stating that the church was no longer Episcopal and that the word would no longer be spoken in St. Michael’s. St. Michaels’s, he said, would no longer send money to the Episcopal Church USA. Smith’s actions were met with outrage from all sides, though Bishop Iker made no public comment. Smith left the Episcopal Church and started his own church, taking many of the St. Michael’s flock with him. At the Episcopal Church of the Holy Spirit in Graham, the day after Robinson’s consecration, the vicar’s office was set on fire and the message “God and Jesus love homosexuals” was scrawled on a wall — and then vandalized and set ablaze again less than two weeks later. The vicar, the Rev. Scott Wooten, suggested in a letter published on the Fort Worth diocese website that the attacks were hate crimes aimed at “orthodox Episcopalians,” brought on by his decision to “take a stand against biblical revisionists.” However, after two people were arrested, police reported that the perpetrators were not gays or gay advocates but rather a couple of bored kids.

Many churches in the area didn’t wait for any official action from the administrative arms of the church. Christ Church Episcopal of Plano is now simply called Christ Church. The church had been one of the ECUSA’s largest congregations, with an average of 2,200 people attending its five weekend services in total. The parish is one of a dozen or so churches that left the denomination over what they see as its drift toward the left. Christ Church arranged to be supervised by Bill Godfrey, Bishop of Peru, and will remain a part of the Anglican Communion. In Fort Worth, despite his threats to the contrary, Iker has said that he has not yet decided to leave the church, according to spokeswoman Suzanne Gill. Many local Episcopalians are waiting to see what happens in September, but the consensus seems to be that Iker will try to take this diocese out of the Episcopal Church. That can’t happen under the national church’s constitution, which says that it overrides all local constitutions. For a legal split to occur on the scale that the dissidents are imagining, two consecutive General Conventions of the national church would have to vote to change the national constitution. These legalities are unlikely to keep Iker from leaving the national church.

Rev. Frank Reaves of St. Martin in the Fields Episcopal Church in Southlake said he doubts that this diocese will remain a part of the national church. “They have disaffiliated themselves with every aspect of the Episcopal Church except for the church pension fund and the medical trust. I think that they are so alienated … that as soon as they can find some viable entity to be a part of, the formal split will take place.” The Very Rev. Ryan S. Reed of St. Vincent’s Episcopal Church in Bedford, who is Iker’s chief deputy, sees a split as likely. “I think if you had a vote today, based on the last four or five years, I think the feeling is that there needs to be separation,” he said. Reed said that at the Fort Worth diocese’s annual convention last year, “There was definitely strong support for [Iker’s] leadership … in terms of differentiating itself from the new direction of the national church. We were trying to make a statement that the national church should think hard about what its doing and where it’s headed.”

Barber said Iker’s support comes from the large number of people who share his conservative views. “I think that Texas is a conservative place. [It’s] conservative politically and religiously, and I think that this is a conservative diocese.” Plenty of people move to this diocese and find it too conservative, he said, “and I think that some of them go to other churches [outside of the diocese].” Merritt Farren, a parishioner at All Saints and treasurer of the Fort Worth Via Media, came to Fort Worth from near Atlanta. He said the Fort Worth diocese is dramatically different from all the other Episcopal dioceses he’s been a part of. “My wife and I have been in at least 10 different places and 10 different parishes, and I was just astounded when we got here,” he said. “The way [Iker] does things is really very poor and not what I would call a very Christian way of doing things. “He was not in favor of women being ordained to the priesthood, which seemed kind of weird because it was so old-hat,” Farren continued. “After the 2003 General Convention, he said that anyone who voted the wrong way [for Bishop Robinson] or who attended the consecration ceremony in New Hampshire was not welcome in his diocese.”

While Reaves, Reed, and Barber all say that their congregations are growing, and the diocese is holding steady in terms of numbers of members, according to several sources, the Episcopal Church, like all “mainstream” Protestant Churches, has been in a steady decline over the past three decades, dropping from 3.6 million members in the 1960s to 2.2 million in 2005. “We lost people on both sides of the spectrum,” said Reaves. “What I’ve tried to do is comfort the middle-ground folks and tell people on both ends to hang on and let’s try to work through this.” In the event of a split in the church, battles over church property would no doubt erupt. When Christ Church in Plano left the Diocese of Dallas and the Episcopal Church, it agreed to pay a lump sum of $1.2 million to the Dallas diocese and assumed the $6.8 million dollar debt, although that amount is only a fraction of the assessed commercial value of the property. But other property disputes may not be so amicable. National church law says that the bishop of a diocese holds its property in trust for its true owner, the national church. In cases where individual local churches have tried to break away from a diocese and there were disputes about who owned what, secular courts have tended to side with the diocese. But so far, no court has ruled on disputes between a diocese and the national church.

The rift between the rival factions of the church cuts deeper than just homosexuality or liberals versus conservatives. Both sides believe that they are the stewards of the traditional teachings of the denomination. Two distinct points of view have emerged from years of struggling with the essential questions of faith. Father Reaves believes that because of science and other factors, humanity has reached a level understanding beyond the authors of the Bible. “Everybody has certain portions of the Bible that are very important to them, and there are certain parts of the Bible that we all commonly reject, such as slavery and things like that,” he said. “When it was revealed that the world was round, we reinterpreted the Bible. Now as far as the homosexual community goes, we’re looking at certain facts which part of the church accepts, and we have to interpret the Bible relative to those newfound truths.” Alternatively, Father Reed is one of a growing number of people who are disturbed by the church’s “liberalism.” “The Episcopal Church is nothing more than a mouthpiece for the culture. The question is, ‘Have we really vowed to live by the apostles’ teaching or not?'” Sexuality and gender issues, he said, “are just the tip of the iceberg.”

Conservatives, he said, have “been outcasts since the creation of the diocese because we didn’t jump on board with the ordination of women. … I’m labeled ‘hate-filled'” because, he said, he’s “not sure that someone who is living outside of what we understand to be God’s ideal for us … in terms of the marriage relationship [should] be in a position of authority.” Some Episcopalians believe that the conservatives are actually destroying the tradition of the Episcopal Church. Hudson said that under Iker’s leadership, this diocese is eroding the core of what it means to be an Episcopalian. “Bishop Iker, his followers, and his allies call themselves traditionalists and conservatives,” said Hudson, who now lives in Austin. “They are neither. They are revolutionaries, and they are busy destroying a humility of mind and gentleness of spirit that have been the Episcopal Church’s best gifts to divided Christianity: a refusal to presume to know the mind of God, a refusal to turn one set of doctrines into an object of worship, a refusal to settle matters of belief and practice once and for all. Bishop Iker’s narrow strictness and stinging certitude are new and alien to an ethos that has taken some five centuries to create and sustain.”

Komechak and Via Media believe there is still an opportunity to salvage their relationship with the rest of the Anglican world. “There needs to be a listening process to find out the experiences of homosexual people and the problems that they face,” he said. Others are comforted by the actions taken by the ECUSA, in reaffirming their position of inclusiveness. “I feel as comfortable and as hopeful as I’ve ever been,” said Sherrod. “The fact that we’ve just celebrated Easter, it’s happened again. We got through Lent, and we got through Good Friday, and now we are the resurrection people again. This church will do the same thing. We will get through Good Friday, and it will be Easter Sunday again in the Episcopal Church.”

You can reach Eric Griffey at eric.griffey@fwweekly.com.