Four thousand miles of smooth blacktop. Six open lanes of road with never a traffic jam.

Four lanes for trucks to keep the 18-wheelers from bothering Joe Motorist. High-speed rail to get you from San Antonio to Dallas in just a couple of comfy hours. Oil, gas, and water lines running from Oklahoma to the Mexican border. Handy motels, shops, and gas stations to keep you from having to get off the road until you hit the state line.

Four lanes for trucks to keep the 18-wheelers from bothering Joe Motorist. High-speed rail to get you from San Antonio to Dallas in just a couple of comfy hours. Oil, gas, and water lines running from Oklahoma to the Mexican border. Handy motels, shops, and gas stations to keep you from having to get off the road until you hit the state line.

That’s the dream of the backers of the Trans-Texas Corridor, the biggest public works project in the history of the state and the most ambitious road project in the USA since Ike decided to connect Maine with California and Wisconsin with Arizona by building the U.S. highway system 50 years ago.

But some people see it more as a nightmare than a dream. They see foreign companies owning the rights to Texas’ infrastructure, whole towns being turned to dust because there won’t be an exit ramp for them, vast stretches of farm and ranching land — close to 1 million acres all told — being gobbled up in a bid to put a feather in Gov. Rick Perry’s cap and eventually in the U.S. Department of Transportation’s cap if the plan is expanded to all 48 contiguous states. They see Texas water being traded for Mexican oil, toll fees as high as 44 cents a mile, “no-compete” clauses leaving Texas’ current free highway system to crumble, and a host of other problems with the gigantasaurus-sized plan.

And the nightmare thinkers are a lot more vocal than those trying to implement the plan — surprising, perhaps, since Perry has hailed it as “the most visionary transportation plan this state has ever seen … . [I]t likely will forever change the way we build roads in Texas.” And the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), has said it will financially benefit the whole state by “injecting billions of dollars in private spending into the state’s economy and creating millions of jobs … .”

If you’re neither part of the grassroots rebellion against it or the state-agency-and-big-contractor cheering section for it, chances are you are still bewildered by the hyperbole on both sides, and the question of what in tarnation this animal called the Trans-Texas Corridor really is. Whatever it turns out to be, the fact is that right now it is a huge pig in a poke for Texans, a massive creature that will transform the state’s landscape, but whose outlines — and price tags and details — are still partly under wraps.

At its simplest, the TTC is not one road but a series of huge transportation corridors connecting the state’s major population hubs. It’s intended to ease traffic congestion along the state’s busiest routes and provide lanes not only for cars, but for high-speed and commuter rail, freight trains and trucks carrying NAFTA goods from Mexico to Oklahoma and eventually all the way to Canada. It will also include a utilities corridor for pipelines and conduits carrying natural gas, oil, water, electricity, and electronic data. In North Texas, the TTC is planned to run between Dallas and Fort Worth, paralleling I-35.

At its simplest, the TTC is not one road but a series of huge transportation corridors connecting the state’s major population hubs. It’s intended to ease traffic congestion along the state’s busiest routes and provide lanes not only for cars, but for high-speed and commuter rail, freight trains and trucks carrying NAFTA goods from Mexico to Oklahoma and eventually all the way to Canada. It will also include a utilities corridor for pipelines and conduits carrying natural gas, oil, water, electricity, and electronic data. In North Texas, the TTC is planned to run between Dallas and Fort Worth, paralleling I-35.

In theory it will boost Texas’ economy by making Texas more attractive to businesses that will see the corridor as a time-saving, and therefore money-saving, way to move their goods. TxDOT said it will also “significantly reduce air pollution” by convincing Texans to travel more by passenger rail rather than cars and by reducing congestion on the rest of the state’s major thoroughfares.

All of that sounds pretty desirable. But when the Texas Legislature passed HB3588, the massive transportation bill authorizing the TTC, in 2003, almost no one understood its final impact — not the politicians voting on it nor the general public.

The executive summary of the bill describes a statewide network of transportation facilities that sounds pretty much like business as usual in the road-building game. But the master plan for the TTC-35, the section of corridor to run parallel to I-35 from Laredo to Oklahoma, released three years after the bill passed, indicates it’s anything but that. The plan, made public only after 175 Freedom of Information Act requests were filed by citizen groups and news media, describes a 1,200-foot-wide corridor to be leased to private companies who will design, build, and maintain their specific sections, setting and collecting all tolls for contract periods ranging from 50 to 75 years. Sections of existing roads that coincide with the corridor — all of I-35 from San Antonio to Laredo, for example — will become part of the toll road. Additionally, motels, gas stations, and stores built within the corridor will be part of the private company’s holdings — and part of their profit package.

But the deal is even sweeter than that. The initial contract signed by the Spanish firm Cintra; their partner on the project, Zachry Construction Corp.; and TxDOT for a 316-mile section of road to be built from San Antonio to Dallas, includes what’s known as a no-compete clause. In this case, it means TxDOT has agreed not to improve any roadways that run parallel to the TTC for the duration of the Cintra lease, unless those improvements had already been approved prior to the signing of the contract.

Perry has still refused to disclose some parts of the contract, on grounds that they contain proprietary information for the Cintra-Zachry partnership. But the sections that have been made public show that Cintra will not be obligated to build more than four car and truck lanes “until and unless it is demonstrated that there is a demand for high-speed rail, commuter rail, freight, and utilities.”

And who gets to decide what tolls to charge on these new roads? Cintra. In the contract, TxDOT agreed that toll prices will be set “at what the market will bear.” A TxDOT news release suggested they would be in the 12- to 24-cent range per mile for autos. Opponents think they’ll more likely be twice that. In other words, the San Antonio-to-Dallas trip could cost a motorist anywhere from $32 to $118 in tolls, plus gas.

Wait, there’s more. Later this month, TxDOT officials will be in Washington, lobbying Congress to exempt from federal taxation any income gained from dividends or partnership distributions by toll road companies.

The tax exemption will be of interest to legislators from many states. The issue of ownership of major portions of the U.S. highway system by private — and often foreign — companies goes far beyond Texas. Cintra, for instance, in partnership with Macquarie (an Australian company), already owns a 75-year lease on 157 miles of the Indiana Toll Road. The state was paid $3.8 billion for the lease, which will allow Cintra-Macquarie to keep all tolls during that time, an estimated total of nearly $12 million.

The tax exemption will be of interest to legislators from many states. The issue of ownership of major portions of the U.S. highway system by private — and often foreign — companies goes far beyond Texas. Cintra, for instance, in partnership with Macquarie (an Australian company), already owns a 75-year lease on 157 miles of the Indiana Toll Road. The state was paid $3.8 billion for the lease, which will allow Cintra-Macquarie to keep all tolls during that time, an estimated total of nearly $12 million.

The ambitiousness and audacity of the Trans-Texas master plan provoked former Texas Comptroller Carole Keeton Strayhorn, during her recent gubernatorial campaign, to call it “the biggest land grab in the history of Texas.”

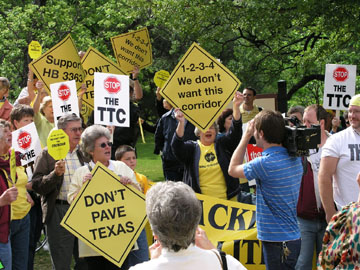

While support for the TTC has come from a small coterie that includes Perry, TxDOT, some federal officials, and businesses that stand to benefit, opposition is gathering from all over the map. On this issue, the Texas Republican Party has found itself in bed with the Sierra Club and independents like Strayhorn, Democrats like Houston Sate Rep. Garnet Coleman, the ultra-conservative property-rights group Stewards of the Earth, farmers, ranchers, and a host of groups created with the sole purpose of trying to stop the TTC.

“The initial plan for the TTC calls for the taking, by eminent domain, of 580,000 acres of private Texas property,” said Terri Hall, regional director of the San Antonio Toll Party. “That’s more than 900 square miles. And there are secondary components to the TTC that would bring that number up to 1 million acres. That’s going to cut the state into pieces.”

While TxDOT downplays the issue of having a series of nearly quarter-mile, non-crossable roadways cutting Texas into a bunch of jigsaw puzzle pieces, it’s very serious to the tens of thousands of farmers and ranchers whose property and livelihoods could be steamrolled by the widest roadway in the hemisphere.

Ron Smith, editor of Southwest Farm Press, said the farmers and ranchers who read his magazine and web site are up in arms. “You’ve got farmers with 500 to 800 acres whose farms are going to be cut in half. The same with ranchers. They make a good point when they say that with the TTC having few crossovers it’s not just going to make their lives difficult, it’s going to drive them out of business.”

Farmers are worried not only about losing valuable property but also about having their properties split, with access to the other-side-of-the-road half a major problem. And although final plans for the TTC have not been drawn as yet, Ric Williamson, chairman of the Texas Department of Transportation, has been quoted repeatedly as telling farmers that they can go ahead “and build a tunnel underneath the road if you want one.”

Such flip comments won’t solve the problem. There is no way to know yet how far apart Cintra-Zachry will build the crossovers, which are extremely expensive since they have to cross so many lanes. If farmers have to move tractors for miles and miles along access road to get to a crossing, it will be costly for them as well as for the traffic on the access roads stuck behind their slow-moving equipment. And think about the problems involved for ranchers having to move their cattle from pasture to pasture, when the move involves herding the bovines down access roads for several miles to the nearest crossover.

Such flip comments won’t solve the problem. There is no way to know yet how far apart Cintra-Zachry will build the crossovers, which are extremely expensive since they have to cross so many lanes. If farmers have to move tractors for miles and miles along access road to get to a crossing, it will be costly for them as well as for the traffic on the access roads stuck behind their slow-moving equipment. And think about the problems involved for ranchers having to move their cattle from pasture to pasture, when the move involves herding the bovines down access roads for several miles to the nearest crossover.

“It could be worse than you think,” Smith said. “Farmers are telling me the only way they’ll be able to work fields on the other side of the corridor will be to set up a second farm headquarters there. That means tractors and other farm equipment that couldn’t possibly pay for itself on a hundred, two hundred acres of land.”

Anna Mowery, a longtime Republican legislator from Fort Worth, said she worked with the Farm Bureau to try to make certain that TTC overpasses would be frequent enough to allow for reasonable farm connections. “I don’t mind telling you that I think we need to do something, and toll roads seem like a reasonable way to go about improving our transportation needs. And what particularly interested me about the TTC was the inclusion of commuter and high-speed rail,” she said. “But what bothered me about the original plan was that farmers might need second tractors to access land cut by the eminent domain-taken corridor.”

So, Mowery said, “I hung in with the Farm Bureau to ensure that the farmers and ranchers would have reasonable access.”

But farmers and ranchers don’t see any assurances of reasonable access in the plan, despite her efforts. The legislator was surprised to be asked just how far apart crossovers would be on the TTC. She didn’t know. And in fact, no one knows if there will be one overpass every 10 miles or every 40. TxDOT, which spoke very briefly and conditionally to Fort Worth Weekly for this story, is silent on the issue. The truth is, there’s been no agreement. And no one, despite Governor Perry’s claim that no public monies will be used to build the TTC, knows who will pay for whatever overpasses there are. There is some question of whether or not TTC builders would pay for crossovers and road connections at all; one section of the law authorizing the project lists the state as being responsible for those.

“Bottom line,” said Mike Barnett, a spokesman with the Farm Bureau, “is we were told to trust TxDOT and Cintra. And we don’t. We are dead set against the whole TTC. And we’ll fight for our farmers and ranchers as best we can to get them the best deal. But right now we have no idea what that will be.”

Nor is it just farmers and ranchers who will suffer. In some places, particularly in the area from San Antonio to Laredo, for instance, I-35 will be incorporated into the corridor — taking a road already purchased by tax dollars and making it a toll road — and whole towns will be cut in half. TxDOT refers questions to its web page and the ominously named Master Plan, which reassures readers that there will be plenty of access to affected towns. But those reassurances don’t jibe with the Cintra-Zachry contract, which calls for the corridor to connect with all U.S. and state highways, but says nothing about duplicating the number of exits that already exist on I-35, or for the building of frontage roads along the new corridor.

And in the southern part of Texas, where I-35 is little more than a two-lane road through towns, or along which towns have grown up, it’s not difficult to imagine that some of those towns will be wholly swallowed up by a 1,200-foot roadway.

But the interest of the operators of the TTC is to make money. They will have a substantial investment to recoup — all components of the TTC combined will have a price tag as high as $184 billion — and it won’t be in their interest to put in 1,200- to 1,400-foot-long crossovers, at a price of $2.6 million each, very frequently. And besides, the TTC builders won’t want to let people off their road too easily. It’s to their benefit to keep them on the TTC as long as possible, and when they do stop, to have them eating and sleeping and buying things at their businesses, not existing ones.

But the interest of the operators of the TTC is to make money. They will have a substantial investment to recoup — all components of the TTC combined will have a price tag as high as $184 billion — and it won’t be in their interest to put in 1,200- to 1,400-foot-long crossovers, at a price of $2.6 million each, very frequently. And besides, the TTC builders won’t want to let people off their road too easily. It’s to their benefit to keep them on the TTC as long as possible, and when they do stop, to have them eating and sleeping and buying things at their businesses, not existing ones.

“I’ve wondered whether those farmers affected by this road would have the right to build motels on their land, or gas stations,” said Mowery. “I haven’t gotten an answer to that yet.”

The limited-access clauses have a lot of people wondering what other time bombs are ticking in the TTC deal and when the public will finally be allowed to see the details.

Maybe you figure that if the tolls are too high on the TTC and the exits won’t let you get where you’re going very well, you’ll just stick to the old roads. Well, good luck. The TTC legislation forbids improvement of any road that runs parallel to the TTC corridors beyond what’s already in the works. That means no beautification, no widening, no new exits or entrances for the life of the contract — 50 years in this case. “Imagine if you live in a little town on a two-lane farm-to-market road that runs parallel to this thing,” suggested former Fort Worth City Council member Clyde Picht. “And then a subdivision gets built, and suddenly you’ve got 3,000 homeowners and cars fighting for space on that two-lane road. Well, you need to widen it to accommodate people. But your hands will be tied.”

Picht said he was surprised to hear about the no-compete clauses. “There should never be no-compete clauses in highway construction. If the toll is too high, let someone else build a road. I hate to see us depart from the traditional system of free roads. And this — well, I’m disgusted with it. After seeing the abuse of eminent domain with the Trinity Uptown project, I think this will be a thousand times worse.”

Hank Gilbert, a farmer, former high school ag teacher, and small businessman who ran unsuccessfully for Texas agriculture commissioner last year, goes further. “They’re going to take a million acres of Texas agricultural and ranch land and pave it over. This is such a huge project it’s almost incomprehensible. And I personally don’t like the idea of taking people’s homes away to build a highway system to facilitate NAFTA to the betterment of companies that sent U.S. jobs down to Mexico to make more money by bringing their goods in tariff-free.”

Gilbert, a Democrat, said it was the TTC — and what he sees as corruption associated with it — that propelled him into running for political office. He’s passionate about how little the general public knows of things like the no-compete clauses. “As best as anyone knows, because so many elements of the contract are not clearly spelled out, no-compete would mean no improvements to any road seen as a viable alternative to getting to a destination that you could reach using the toll road. But we don’t yet know what that proximity is. And in all likelihood, that would be determined by Cintra or whomever leased the road,” he said.

The no-compete clauses have raised the ire of Republicans as well, including State Sen. John Carona of Dallas, the new chairman of the Senate Committee on Transportation and Homeland Security. Carona recently told Texas Monthly that “Within 30 years’ time, under existing comprehensive development agreements [like the one given Cintra], we’ll bring free roads in this state to a condition of ruin.”

Gilbert is also unsure what the public’s financial investment in the TTC will be. “The governor and TxDOT signed off on a contract not made public in many parts, so we don’t have any idea what our fiscal responsibility will be. We do know that initially this will be a roadway with four lanes in each direction, two for passenger cars, two for trucks. There’s no guarantee they’ll have to put rail in, or utilities. The contract says things like ‘if and when they are deemed necessary.’ Well, if and when means when they look like they’ll be profitable. But who knows if that means they or us are responsible for putting them in at that time, because Governor Perry isn’t releasing those parts of the contract.”

Perry’s also not releasing any information on what the tolls will be, though, based on TxDOT estimates, the cost of, say, a daily commute of 50 miles round-trip would be about $12 a day, or $60 a week. And regardless of how much pocketbook pain that causes, it might be the only option available — which is, of course, the purpose of the no-compete clauses.

According to Perry and TxDOT, financial constraints have pushed the state into a corner, requiring that they find new ways to finance road construction to accommodate Texas’ fast growth.

TxDOT chief financial officer James Bass explained that his agency collects about $7 billion annually from federal and state gas taxes, vehicle registrations, and a few other sources. Most of that goes toward maintaining existing roads, agency overhead, and paying for right-of-way and design costs for new roads. By law, 25 percent of state gas tax revenues are diverted to public schools. What’s left is about $700 million a year for actual construction of new roads — not nearly enough to keep up with the needs, Bass said. “And it’s only going to get worse,” he said. “With the needs that have already been identified to expand the system, between now and 2030 there will be an $86 billion shortfall.”

From the road-builders’ — and politicians’ — point of view, the passage of HB3588, by allowing existing roads to be turned into toll roads and new toll roads to be built, provided a way to develop the state’s road system without increasing taxes.

“So what we’re looking at is innovative public-private partnerships to raise those funds,” said TxDOT spokesman Michael Peters. In theory, said Peters, sums like the $1.2 billion paid to Texas by Cintra-Zachry for the right to design, build, and operate the 316 miles of TTC-35 will pay for other badly needed TxDOT projects.

TTC supporters say that’s only the beginning of the project’s financial benefits. An October 2006 study done by the Perryman Group of Waco for TxDOT predicted that, once the corridor is complete, business activity along it would boost the gross state product by almost $666 billion and generate 3.7 million permanent jobs.

The report was everything Governor Perry and TxDOT hoped and paid for. And the alternative to the TTC, according to TxDOT, would be to increase the state gas tax from 20 cents to $1.40 a gallon.

Baloney, say skeptics, who see many ways to make up the shortfall in highway construction money without resorting to the TTC strategies.

The first move, they say, should be to stop looting the state gasoline tax fund. Several papers released by Bexar County Commissioner Lyle Larson, who opposes toll roads, reveal that the highway fund has lost $10 billion in the last 20 years. “More than half of the total money diverted from road construction, $5.4 billion, went to fund the operations of the Department of Public Safety,” he told a San Antonio radio audience in October. Another $115 million went into the state’s general fund, and millions more went for a computer system for the state comptroller’s office, and to the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, arts commissions, and various politicians’ pet projects.

The first move, they say, should be to stop looting the state gasoline tax fund. Several papers released by Bexar County Commissioner Lyle Larson, who opposes toll roads, reveal that the highway fund has lost $10 billion in the last 20 years. “More than half of the total money diverted from road construction, $5.4 billion, went to fund the operations of the Department of Public Safety,” he told a San Antonio radio audience in October. Another $115 million went into the state’s general fund, and millions more went for a computer system for the state comptroller’s office, and to the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, arts commissions, and various politicians’ pet projects.

Even despite such diversions of money, another recent report, commissioned by another state agency, suggests that the highway construction fund could cover most of the roadways Texas needs, with a relatively small immediate increase in the state gas tax, and more increases through the years. The report, released in November 2006, was produced for the Governor’s Business Council by the Texas Transportation Institute of Texas A&M. According to the study, $66 billion of the supposed $86 billion shortfall — the money needed for the eight largest urban areas — could be produced by raising the gas tax by 8 cents and tying future increases to changes in highway construction costs. David Ellis, one of the report’s authors, said that the indexing, over the next 25 years, would increase the state gas tax from the current 20 cents to about 92 cents.

Compare that to the costs of privatized toll roads like the TTC. If an average driver uses roughly 1,000 gallons of gas annually, the 8-cent gas tax hike would amount to $80 a year. Even gas-guzzlers would pay no more than double that. But a 50-mile daily commute at 25 cents per mile would come to $62.50 a week — or about $3,000 a year. And even with a 92-cent hike over the next quarter-century, the costs would still be considerably lower than toll roads at their current projected cost.

“But our report doesn’t make the gas tax out to be a silver bullet,” Ellis cautioned. “We’re going to need a whole toolbox to get these things built and maintained. And we don’t exclude tollways from that mix.”

The list of objections to the TTC is long enough to draw all kinds of groups to oppose it. The huge costs, the loss of immense tracts of agricultural land and major problems caused for farmers and ranchers, the costs and controversy associated with making currently free highways into toll roads, the displacement of thousands of people, privatization of state infrastructure, and the governor’s refusal to release key documents about the initial TTC contract — all have combined to produce a groundswell of grassroots opposition.

The list of objections to the TTC is long enough to draw all kinds of groups to oppose it. The huge costs, the loss of immense tracts of agricultural land and major problems caused for farmers and ranchers, the costs and controversy associated with making currently free highways into toll roads, the displacement of thousands of people, privatization of state infrastructure, and the governor’s refusal to release key documents about the initial TTC contract — all have combined to produce a groundswell of grassroots opposition.

Environmentalists are also concerned that a fenced-in, or otherwise uncrossable road, as the TTC is assumed to be, may have severe repercussions on the migration of land animals or their feeding habits. Those concerned with terrorist activity wonder about the potential danger of putting utilities together in a single corridor that might make an attractive target. Those who worry about public safety are concerned that a road with few entrances and exits, and with rail and utilities in its center, will present difficulties for emergency vehicle access. People concerned with illegal immigration suggest that a road this large originating in Mexico will only increase the flood of illegal immigrants. Truckers are worried not only about the potentially exorbitant toll costs but about truck safety, since Mexican truckers will be permitted to enter the U.S. without U.S. driving credentials or vehicle safety inspections.

“The only solution is a moratorium on not only the TTC but all toll roads, statewide,” said Rep. Coleman. “I submitted a bill to that effect in the last legislative session, but Mike Krusee, chairman of the House Committee on Transportation and author of HB3588 … wouldn’t let it out of committee. This is about cronyism and creating Lexus lanes and paying pals. To invest [this] kind of money … in a superhighway when we could invest it in high-speed rail is ridiculous.”

And TxDOT knows it, he said. “What ought to tell people something is wrong with the Trans-Texas Corridor is that TxDOT has gone on a marketing campaign to push this down our throats.”

Coleman said he also believes TxDOT is sitting on road construction that’s already been authorized, in order to keep traffic congestion bad in Houston. “I believe they’re doing it so that people will get so fed up with congestion that they’ll welcome toll roads and the TTC,” he said.

This session, he plans to reintroduce both his toll road moratorium bill and a bill to prohibit TxDOT from advertising the TTC. “This whole TTC has to be stopped. And people are beginning to get it, that it must be stopped. I believe we’re making headway on this issue.”

Can a project with this much momentum and political clout behind it be stopped?

“Anything can be stopped.” he said. “It just takes the will of the people.”

You can reach Peter Gorman at peterg9@yahoo.com.

Your style is so unique in comparison to other folks I’ve read stuff

from. Many thanks for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I will just

book mark this web site.