Peewee Walker remembers the drought of the ’50s and the one prior to that that turned so much of the plains into the Dust Bowl. He’s been farming or ranching most of his 91 years in the Everman area. Those bad times felt pretty much like what’s happening now, he said — except he’s got air conditioning this time around. Other than that, “I’d say they’re pretty well equal.”

Peewee Walker remembers the drought of the ’50s and the one prior to that that turned so much of the plains into the Dust Bowl. He’s been farming or ranching most of his 91 years in the Everman area. Those bad times felt pretty much like what’s happening now, he said — except he’s got air conditioning this time around. Other than that, “I’d say they’re pretty well equal.”

R.W. Looper keeps a couple of dozen cows on 220 acres near Azle, not far from the place where he was born 82 years ago. He thinks the current drought is a match for what he experienced in the ’50s. “It was dry as heck then, but I don’t know if it was any drier than it is now,” he said. “It was two or three months into this summer before I got any rain here. I still don’t have any water in the tank. I lost a big oak tree out there by the barn.”

The dryness that has lingered here for most of the past decade, along with the severe heat of this past summer, is hurting farmers and ranchers again, but it’s also affecting cities and towns. Underground water tables are dropping, wells are going dry, and lake levels have dropped low enough to reduce some reservoirs to parched mud and puddles. Texas rainfall has traditionally varied widely, but more and more, the pendulum is swinging toward the dry side.

“Our aquifers just don’t have time to recharge,” said Aledo Mayor Kit Marshall. Her little town just west of Fort Worth, which has depended on a half-dozen community water wells, saw its storage tank levels fall so low this summer that it implemented emergency rationing. The city is now negotiating to buy water from Fort Worth.

The blame game is heating up as more and more rural households are losing water, their wells slowing to a dribble or petering out completely.

Rampant growth across North Texas is accentuating the problem — the area is one of the fastest-growing in the country, with a population that’s expected to double in less than 50 years. More and more subdivisions are covering up the pastures, with more homes each year being built that depend on well water — but inhabited by city folks who expect not just water to drink but enough to turn their prairie plots into wide green lawns of St. Augustine, maybe with a pool out back. Or maybe even an island surrounded by a moat, like at least one Parker County resident built. And making matters worse is the Barnett Shale boom, whose drillers aren’t just sticking straws into gas deposits. They’re using millions of gallons of water a month in their “frac” drilling process, sucking out groundwater that nearby water-well users believe is affecting their supplies.

Where’s a water cop when you need one?

Turns out, there aren’t many. In Texas, it’s open season on water, with few rules and fewer enforcement powers for regulating those who are draining one of the state’s most precious resources. At the same time, it’s getting harder for the water suppliers — agencies like the Tarrant Regional Water District — to get permits to build the reservoirs that much of the state relies on for water. That’s not surprising, since every new reservoir means the inundation of thousands of acres of farmland and creates a host of environmental and other concerns. And even when permits are granted, the suppliers are having to go farther and farther away to build the reservoirs or tap into existing ones.

The first part of that equation — the lack of controls on use of groundwater — may be about to change. With horror stories of water wells (including lots of them near gas wells) going dry in Tarrant, Parker, and Wise counties, residents are demanding action. City and county officials are considering options that could limit water use and, as a result, slow down the rate of growth in outlying areas. And state lawmakers expect a flurry of bills on the subject when the Texas Legislature convenes next year.

“I think you’re going to see water is one of the top issues this January,” said State Rep. Phil King of Weatherford.

In the long run, North Texas may actually be in better shape than it looks. The group of water agencies in the 16 counties that make up what the state calls Region C have in place a water supply plan that, on paper, looks comforting. It takes into account the zooming population and development growth and calls for more and longer pipelines to places like Toledo Bend Reservoir, the possible purchase of water from Oklahoma, and construction of new reservoirs.

But there are questions about whether the area’s current water resources are going to be enough to last until then. In the short run, North Texas appears to have been caught with its pants or, more accurately, its lakes down. People are wondering how long the current drought might last — and we’re still in a drought, despite recent rains — and how seriously that could affect the water situation.

But there are questions about whether the area’s current water resources are going to be enough to last until then. In the short run, North Texas appears to have been caught with its pants or, more accurately, its lakes down. People are wondering how long the current drought might last — and we’re still in a drought, despite recent rains — and how seriously that could affect the water situation.

“What we tend to do is hope we can get through things and it will rain,” said former Fort Worth City Council member Clyde Picht, who ran unsuccessfully this year for a spot on the board of the Tarrant Regional Water District. “Our short-term plan is hoping for a wet year next year.”

Even if it rains for the next 40 days and nights, though, change is coming. North Texas is entering a new era, and water conservation is about to become a way of life.

The oil and gas industry didn’t send many representatives to the Parker County courthouse on Monday morning, when county commissioners and residents gathered to hear a report by a state ground-water expert. Maybe the drillers were there and didn’t identify themselves for fear of being tarred and feathered. The standing-room-only crowd didn’t have much good to say about an industry that uses massive amounts of water with little oversight.

Others blame the crowds of suburbanites for moving to the country and trying to maintain “city yards” — lush green lawns — with no regard for the effects of such landscaping on water sources.

Others blame the crowds of suburbanites for moving to the country and trying to maintain “city yards” — lush green lawns — with no regard for the effects of such landscaping on water sources.

“It’s sickening, it really is,” said Randal Peck, a Weatherford-based water well driller. “People are making their yards look like golf courses. I’m not saying the gas companies aren’t doing any harm — they are. But they aren’t the main harm. It’s the subdivisions.”

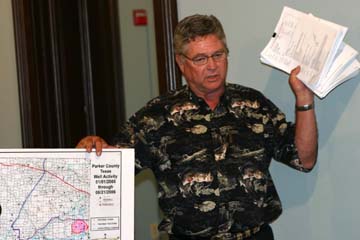

A Texas Water Development Board study of 11 test wells in Parker County showed declining underground water levels over the past few years. “There has been a lot of pumping in the Dallas-Fort Worth area that has drawn the water down,” the agency’s groundwater resources director, Robert Mace, told the crowd.

Rural areas that have long relied on groundwater are finding a thirsty suburbia marching toward them. Every subdivision means another slew of houses; often, each house has its own water well with unlimited access to free water, at least until their wells run dry. Then it’s a mad scramble to pay many thousands of dollars to dig a deeper well or to buy water and haul it to their homes for drinking, bathing, and washing clothes. Or they pray that a municipality stretches water lines to them in their lifetimes without charging a small fortune to hook up to the source.

Two months ago, Kathy Chruscielski was a Parker County resident “blissfully unaware” of the growing water problems there. Then water well drillers began reporting dry wells. Chruscielski and other residents were distressed to learn that gas drillers have flocked to the area, using tons of high-pressure water to blast through rock and push out natural gas. In August, Chruscielski formed the Parker Area Residents Committed to Halt Excessive Drilling (PARCHED) and crusaded to expose the industry’s water usage and to demand more oversight. Only two months later, she’s already regretting her group’s choice of name.

“After you start doing the research and looking at the numbers, oil and gas is just a component of a larger problem due to the growth,” she said. “Our problem is more acute because half of Parker County is on some kind of well water.”

A 2004 water study in Parker and Johnson Counties put it plainly: “Groundwater supplies are inadequate to meet future demands.”

Tarrant County isn’t immune either.

“I never anticipated a water problem,” said Jim Stegall, who runs a plant nursery in southeast Fort Worth. “There’s always been water. Never, ever have we had any wells go out.”

That changed this summer after gas drilling started nearby. Shallow wells that had supplied him with cool, clean water for two decades went dry temporarily and remain weak. Other nurseries around him have had similar problems. It’s hard to know who to blame, and it doesn’t do much good to blame anybody. Underground water is there for the taking, and the guy with the biggest pump wins.

That changed this summer after gas drilling started nearby. Shallow wells that had supplied him with cool, clean water for two decades went dry temporarily and remain weak. Other nurseries around him have had similar problems. It’s hard to know who to blame, and it doesn’t do much good to blame anybody. Underground water is there for the taking, and the guy with the biggest pump wins.

The nursery owners themselves use plenty of water. And why not? Water in Texas has flowed like beer at a frat party for years — a buck for a thousand gallons from some municipal water systems, free if you have your own well. No wonder new homeowners feel no compunction about using so much water each year, planting thirsty grass and shrubs and dousing them until they have the greenest paradise around.

Texas’ “rule of capture” law allows landowners to drill for all the water they want, to use or sell, regardless of the effect on neighboring wells. That’s how a catfish farmer in San Antonio was able to pull so much water from the Edwards Aquifer that an entire city’s main water supply was threatened in 1991. Ron Pucek opened the Living Water Artesian Springs catfish farm, using an enormous pump to suck millions of gallons of water a day from the same underground aquifer that was supplying the city’s residents. Water captured by Pucek was estimated to match the usage of 250,000 households, or a fourth of the city’s population. The city tied him up in court for years by enforcing a law about water discharge in rivers. The city ultimately spent more than $30 million buying his property, assets, and water rights.

Challenges to the law, which was case law long before it was passed as a statute in 1904, have been unsuccessful. Texas courts have protected it even though many other states have adopted “reasonable use” laws for groundwater. In 1997, the Texas Supreme Court considered a landowner’s claim that his groundwater source went dry because of extensive pumping at a nearby Ozarka water facility. The court upheld the law, but justices urged lawmakers to address groundwater issues, with the unstated threat that a failure to do so might result in overturning the rule of capture. About half of the state’s freshwater use comes from groundwater.

Groundwater conservation districts have been around for 50 years, but few counties adopted them until the past couple of decades. Growing demand for dwindling water supplies typically prompts an area to begin regulating. Now half the counties in Texas have created such districts, although, so far, none exist in Tarrant or surrounding counties (Erath County is the closest). Most often, the districts are authorized by special legislation introduced by local lawmakers.

The districts aren’t exactly toothless, but they have limited power. The Barnett Shale formation, which lies underneath a dozen counties in this area, is attracting gas drillers like never before, and they are scrambling for water wherever they can get it, including from water wells. Parker County officials considering a ground-water conservation district discovered something that Fort Worth Weekly first reported in June 2005 — oil and gas companies enjoy exemptions from regulation by the districts.

Domestic wells also are exempt. Residents at Monday’s Parker County water meeting wondered why they should bother to create a groundwater conservation district if it can’t control homeowners or the oil and gas industry. Mace said a district collects data for future water planning, helps educate the public about conservation, and offers more governmental influence to put pressure on industries that overpump. Districts can regulate municipal wells and the occasional large-scale user that pumps more than 25,000 gallons a day.

Domestic wells also are exempt. Residents at Monday’s Parker County water meeting wondered why they should bother to create a groundwater conservation district if it can’t control homeowners or the oil and gas industry. Mace said a district collects data for future water planning, helps educate the public about conservation, and offers more governmental influence to put pressure on industries that overpump. Districts can regulate municipal wells and the occasional large-scale user that pumps more than 25,000 gallons a day.

King, the Weatherford legislator, is organizing a meeting of officials in Parker and Wise counties to establish a cooperative game plan. Prior to the current water woes, residents and various officials had shown little interest in water regulation. “Most of us who have moved to Parker County have moved to get away from large city oversight,” he said.

Sentiments are changing, and more people are telling him they want to increase surface water supplies and to limit groundwater use. King, though, wants to make sure he has all his facts before making changes, and that’s been a challenge. “The thing that shocked me is how little information is available,” he said.

Well diggers say they are noticing shrinking water tables, and some cities have done their own testing and noted lower groundwater levels. Two aquifer studies are currently under way, one by the Texas Water Development Board and another commissioned by Barnett Shale gas producers. King expects to meet with various city and county officials by year’s end to discuss options, something Parker County commissioners have already begun debating.

“It’s an effort to get the leadership of all the cities and [Parker and Wise] counties together and hear a presentation from a hydrologist and a water attorney and walk us through our options and help us make those decisions,” King said.

Another way to save water is to slow down the developers who are blanketing the landscape. Parker County commissioners are studying whether to force developers to prove they have sufficient water supplies before allowing them to build new subdivisions. Regulations such as that will live or die by the details. They can be tough, forcing expensive studies by developers and throttling growth, or they can be written so vaguely as to have no effect.

“We’ve got a drought, we’ve got tremendous growth, we’ve got overuse of the water by the people, and then we’ve got the gas well fracturing,” said Parker County Commissioner Jim Webster. “It is the perfect storm for the water table, which has been dropping for the past 20 years, but now it’s dropping much more than ever because all of these things are coming together.”

Residents with lush lawns are beginning to “feel self-conscious,” said county research coordinator Fay Green.

At Webster’s urging, Green has begun compiling information on water wells to determine the source of problems. Homeowners, on average, use about 125,000 gallons a year. Gas companies can use 50 times as much in a month on a drilling job. Of 1,874 water wells examined so far, gas companies drilled 119 to provide water for frac drilling. Gas drillers like to say they tap into the deep Trinity water aquifer, but Green’s research showed different. About half the water wells drilled by gas companies were in the shallower Paluxy aquifer relied on by most homeowners,

At Webster’s urging, Green has begun compiling information on water wells to determine the source of problems. Homeowners, on average, use about 125,000 gallons a year. Gas companies can use 50 times as much in a month on a drilling job. Of 1,874 water wells examined so far, gas companies drilled 119 to provide water for frac drilling. Gas drillers like to say they tap into the deep Trinity water aquifer, but Green’s research showed different. About half the water wells drilled by gas companies were in the shallower Paluxy aquifer relied on by most homeowners,

Green and Parker County “water wrangler” Freddy Detherage mark the county’s water and gas wells on a map, using colored pins. Red pins designate water wells gone dry. So far, 16 homeowners have reported dry water wells to the county, although water well drillers say they’ve heard complaints from many others about dead or dying wells. Most were near gas wells.

“They’d dug gas wells within a mile of most of the water wells that had gone dry,” Detherage said. “They’d started pumping mud, the water table had lowered so.”

Aledo, one of the towns most severely affected, has responded by applying for a loan from the Texas Water Development Board to pay for pipelines to connect to Fort Worth’s water supply. That could take two years or more.

“We have known for a long period of time that our wells would not supply our growth,” Aledo’s mayor Marshall said. “Surface water is the solution.”

A solution it may be — but not an endless one. In the next several decades, North Texas could run into trouble on that score as well.

Lakes around Fort Worth are pleasant places to put a line in the water, to sail on breezy days, or to retreat from the temperatures on the increasing number of hot, hot, hot days. Since the mid-20th century, they’ve also been a major line of defense against the Trinity’s floods. But they serve an even more basic purpose: Together with the Richland Chambers Reservoir near Corsicana, they provide 95 percent of Tarrant County residents with water.

Those lakes look like salvation to towns like Aledo. And in fact, the gradual depletion of groundwater will mean an ever-growing reliance on surface water in North Texas.

Many of those lakes receded to historic lows this summer. Marinas have struggled to survive as diminishing water levels have left boats sitting on dry lake bottoms. Lake Bridgeport is more than 16 feet low, Benbrook Lake is 12 feet low, and most other lakes have suffered.

“You go look at Lake Weatherford and it’s a pothole,” Peck, the Weatherford water well driller, said.

While there are plans to build four more reservoirs in the next 50 years to serve the region’s water needs, some fear that new pipelines — literally or figuratively — won’t reach here in time to avert major problems.

While there are plans to build four more reservoirs in the next 50 years to serve the region’s water needs, some fear that new pipelines — literally or figuratively — won’t reach here in time to avert major problems.

“We have insufficient water to provide for the growing population in the future,” said J.R. Kimball, a local realtor who, like Picht, ran unsuccessfully for the Tarrant Regional Water District board. “We need some more reservoirs, and it takes 20 to 30 years to go through the process to get a reservoir approved and built. If we’re going to have water for the future, we should have started yesterday.”

Still, Kimball feels previous board members have done well to create our current water system, and current board members are on line to ensure future supplies. “They are very forward-thinking and planning and have a history of providing us with all the water we need to be where we are today,” he said. “I don’t think there is a better water district or board in the state.”

Tarrant Regional Water District is part of a larger group of water suppliers and planners that focus on surface water. And have no doubt, it’s what’s on top that is being counted on to sustain the vast Region C. State lawmakers divided the state into water regions in 1997, figuring localized planning districts were the best way to study water sources and, ultimately, create a statewide plan.

Region C includes North Texas Municipal Water District, Dallas Water Utilities, and the Tarrant Regional Water District. Fort Worth, Arlington, and Mansfield are just a few of the Tarrant district’s 30 customers that rely on the four reservoirs, pumping stations, and miles of pipelines and floodway levees.

More water sources will be needed to handle the hordes of people making their way to North Texas. Without more water, shortages will stagnate growth and economic development. The Texas Water Development Board predicted that, without new water supplies, the area’s 2050 population will be held to 6 million rather than the anticipated 9.4 million, employment will be limited to 2.6 million instead of 4.4 million, and incomes will be $109 billion instead of $171 billion.

Water planners say that at least one more lake is needed by 2030. The three leading possibilities include building the proposed Marvin Nichols reservoir on the Sulphur River near Bonham, although the controversial plan would require flooding thousands of acres of farms and forests and has angered many northeast Texans.

Oklahoma’s healthy reservoirs offer another source, but selling water across state lines can be tricky. Oklahoma currently has a moratorium on water sales until a study is completed on the state’s supply, although local officials say there is water aplenty there. Dave Marshall, Tarrant Regional Water District’s engineering services director, said the best option may be building a pipeline to Toledo Bend, a healthy reservoir near the Louisiana border.

There are disadvantages. Toledo Bend is 225 miles away, and it is more expensive to pump water “uphill” from east to west. Water gets more expensive for every mile further it has to be pumped.

Building a reservoir isn’t a piece of cake either. Texas is a strong property rights state, and eminent domain condemnations can be expensive and time-consuming. It’s a process guaranteed to make landowners furious: Properties slated to be flooded get purchased at fair market value, while others are suddenly transformed into valuable lakefront property. Legislators get pressure from numerous groups that balk at turning land into lakes — conservationists, farmers, ranchers, developers, and property-rights advocates.

What’s more, getting a state permit to create a reservoir is becoming increasingly difficult, said Jim Parks, chairman of the Region C water planning group.

For all those reasons and more, the water planners know better than to rely solely on the idea of more surface water to meet North Texas’ needs.

The Science Channel’s recent show “What If: The Oil Runs Out?” looked ahead to 2016 and showed a frantic society grappling with oil shortages. Dramatizations showed people turning on one another as oil supplies became more scarce and expensive. Neighbors argued, stole, hoarded gas, and blamed each other for the world’s woes.

The scenes are hardly implausible considering the amount of arguing and blaming that’s already begun over water.

In North Texas in recent years, cities have implemented rationing rules that relied on neighbors squealing on neighbors about sprinkler misdemeanors. A water dispute in Fort Worth this summer led to an elderly woman shooting at a neighbor. And tempers flared when water wells began going dry in subdivisions outside the city limits. One woman told the Weekly that her neighbor dug a tank, stocked it with fish, and then kept a garden hose running 24-7 to keep it filled. When her well began having trouble, she put two and two together and eyed her neighbor.

Since controlling the weather is impossible and stifling growth in North Texas is a dirty word, short-term plans for water will rely more heavily than ever on conservation. This summer, Fort Worth was one of many cities that banned outdoor watering between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m., when large amounts of moisture are wasted in evaporation. Get used to the cutbacks: Water rationing will be reinstituted in future years between June 1 and Sept. 30. Other new rules set fines for broken sprinkler heads, water running down the street, watering in the rain, etc., and will be enforced year-round.

“That’s a big step for Fort Worth, but we feel it’s a very positive step toward the future,” Fort Worth public education specialist Scheretta Scott said. “Water conservation is a growing issue, and in the future, to qualify for grant funds and financing, you have to prove you have done as much as you can do toward conservation.”

Between June 1 and Aug. 30, the city received 1,483 complaints of watering violations. “They’re not just trying to tattle, they’re trying to bring forth change,” Scott said. She added that most of the comments the city received about rationing were positive.

The city issued warnings and made home visits in some cases, but no citations were issued. Next year will be different.

“This first year was more about educating; it’s going to be more aggressive next year,” she said.

Getting the average Joe to adopt conservation as a way of life becomes easier when water woes scare people. Water-starved San Antonio implemented conservation programs 15 years ago when the Edwards Aquifer levels were dropping. Limiting the amount of water a household or business can use is commonplace there. El Paso, Austin, and other dry cities have followed suit.

The impact of conservation is more than a drop in the bucket. Tarrant County saw an 11 percent reduction in water use this summer after rationing was enforced in Fort Worth, Arlington, and other cities.

How much is 11 percent? “It’s about a difference of around 60 or 70 million gallons a day,” the local water district’s Dave Marshall said. “It was really significant. I was amazed.”

In recent years, the state has required water suppliers to develop conservation plans as a condition to getting funding from the Texas Water Development Board or permits from the Texas Commissioner on Environmental Quality to build new reservoirs. The idea of creating new lakes without first trying to conserve water no longer flies in Austin.

“Up until now, the perception has been that we haven’t conserved as we should have or could have,” Parks, the Region C chairman, said. “It’s not true in all cases but it’s the perception.”

Without permits to build lakes, planners have to consider other ways to provide the needed H2O. Only about 18 percent of this region’s future water supply is expected to come from new reservoirs. “A lot of people think new reservoirs are all that we focus on when in fact it is less than one-fifth of the total plan,” Parks said.

A larger percentage of our future water supply — 26 percent — is expected to be freed up through conservation and recycling, such as reusing wastewater for irrigation at golf courses, football fields, parks, and municipal properties.

North Texans have typically ignored conservation and resisted rationing, perhaps spoiled by the area’s abundance of lakes and groundwater. The worse things get, the easier it will be for officials to sell conservation. Education is key. “Once people understand what the issues are and understand the facts, they will generally try to assist and accommodate in the solution,” Parks said.

Concerted efforts by residents, municipalities, counties, and industries, including oil and gas drillers, have the greatest effect on conservation, but that can be difficult to pull off.

Joe Hines is the public works director in Willow Park, a Parker County community that has had its own share of water disputes. He’s watched many of the state’s various water agencies promote conservation with limited success. The problem is, if one city or county adopts strict conservation policies, developers look to neighboring cities and counties without regulations.

“From that perspective, it needs to be driven from a legislative level, making water conservation fundamental as a state rule,” he said.

Residential areas use the most water and can make the biggest difference, he said. “Getting the information out to consumers is really the only way it is going to be successful,” he said. “We’ll meet with a lot of resistance, but if you would get conservation started on the front line, we could have a tremendous impact.”

Installing low-flow toilets and shower heads, planting drought-resistant landscaping, watering smaller areas of the yard during droughts, fixing water leaks, and ensuring that sprinkler systems are working efficiently are just a few ways that homeowners make a difference. Every little bit helps: The Region C water plan assumes that widespread use of low-flow plumbing fixtures by 2060 will slow the region’s growth in water demand by 5 percent.

Consumers can go along voluntarily or be dragged along kicking and screaming. For instance, San Antonio limits household water wells to using no more than 50,000 gallons a year, less than half of the average household water use in North Texas, Hines said. “Wouldn’t you rather voluntarily conserve and end up at 75,000 [gallons allowed] rather than 50,000?” he said.

Water officials have another ace in the hole if consumers don’t cut back voluntarily — higher prices.

“It’s going to take some real leadership, and it’s going to take each one of us doing our part,” Hines said. “We’re not out of water, but we’re overusing the water we have today. We could turn this around if we chose to. We’re not in a crisis yet, but it’s approaching that point.”

You can reach Jeff Prince at jeff.prince@fwweekly.com.