With Rick Perry making his bid for the U.S. presidency, you can expect to hear in his rhetoric many familiar tropes of Texas identity, especially as the governor attempts to set himself apart from the competition. Most likely, he will trot out conflicting myths: of Western anti-government individualism (Perry’s book title, Fed Up!, says it all) and of Southern independence (remember those “jokes” about secession?). While they may be the competing strands of Texas’ self-image, neither is entirely accurate. And in any case, the Lone Star State of mind is far more than the sum of its southern and western parts.

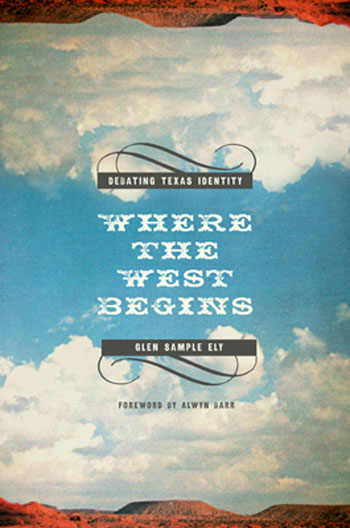

In his first book, local documentary filmmaker Glen Sample Ely tackles these longstanding battles for the soul of Texas. Published earlier this year by Texas Tech University Press, Where the West Begins: Debating Texas Identity is at once a feat of original research and a thorough engagement with historical memory (public, popular, and academic). A slim volume, the book focuses specifically on West Texas history and makes for a quick read, thanks mainly to the absence of jargon. Still, Ely is a serious historian and takes pains to avoid whitewashing the narrative, bearing witness to the roles and treatment of groups –– Mexicans, blacks, indigenous Americans, and even the German immigrants –– too often left out of the story by other tellers. This is the same state, after all, that’s gained national notoriety in recent years for sanitizing its history textbooks; fitting, then, that Where the West Begins should reveal Texas identity to be rich and complex –– but not without its painful chapters.

In his first book, local documentary filmmaker Glen Sample Ely tackles these longstanding battles for the soul of Texas. Published earlier this year by Texas Tech University Press, Where the West Begins: Debating Texas Identity is at once a feat of original research and a thorough engagement with historical memory (public, popular, and academic). A slim volume, the book focuses specifically on West Texas history and makes for a quick read, thanks mainly to the absence of jargon. Still, Ely is a serious historian and takes pains to avoid whitewashing the narrative, bearing witness to the roles and treatment of groups –– Mexicans, blacks, indigenous Americans, and even the German immigrants –– too often left out of the story by other tellers. This is the same state, after all, that’s gained national notoriety in recent years for sanitizing its history textbooks; fitting, then, that Where the West Begins should reveal Texas identity to be rich and complex –– but not without its painful chapters.

Looking back to the Civil War, Ely shows that many people in West Texas opposed secession and viewed the Confederacy with ambivalence –– but not because frontiersmen (and -women) supported the abolitionist cause. While relatively few in West Texas practiced slavery, the region was characterized by a distinctly Western brand of segregation that affected Mexicans and blacks alike (and held well into the 1960s). Instead, West Texans simply depended on the federal government for infrastructure and economic development. Not only did several Western counties vote against secession, but the region quickly fell under Union control during the war, thanks to the fact that many local settlers fled the region.

That West Texas saw depopulation in wartime shouldn’t surprise anyone. But Ely shows that the conventional wisdom, held by several generations of historians and memorialized on official state markers, has perpetuated some big myths about how and why this happened. Some refuse to believe that the Texas Rangers and Confederate soldiers were unable to adequately protect the region. The Rangers were not, however, operating at full capacity, as many of its men were conscripted into the Southern army; countless others, who could have joined up with either force, simply defected to Mexico and New Mexico. More often than not, the West Texas fort towns that Union soldiers swept through had become ghost towns by the time the troops in blue arrived. And that has led others to suggest that land out West was simply not worth protecting. However, the Confederates repeatedly tried –– and failed –– to regain control, and several of the region’s most important trails, which would benefit post-war development greatly, had already been blazed in the 1840s and ’50s.

If an early dependence on the federal government helps explains West Texans’ reluctance to take up the Southern cause, it also does some damage to the Western myth of rugged individualism. Help has always come from Washington, which, in the early years, nurtured the conditions that facilitated and supported the effective settling of the West, from military protection to economic incentives to the laying of roads and railway lines. This continued into the 20th century with land and agricultural subsidies. The government had to step in –– hard work and private capital alone, Ely illustrates, couldn’t jumpstart the West’s development. And for good reason: West Texas, like the American West generally, is fundamentally arid. Here, too, this trademark individualist streak has run counter to the ecological reality. In outlining the region’s history of resource use from mid-19th-century settlement into the present, Ely notes the scientific consensus that such abuse could very likely precipitate a repeat of the Dust Bowl.

The trajectory of race relations in West Texas, Ely writes, has moved “from cooperation to segregation to cooperation once more.” From the short-lived days of the Republic of Texas on through the 1880s, Anglo settlers and Tejanos enjoyed a level of comity that, while tenuous and far from complete, was unheard of among other minorities in the South and North. Mexican-Americans here held government office, and throughout this entire period whites and Mexicans intermarried extensively. (Of course, there was a double standard: White women, whose numbers were disproportionately low on the frontier, were shamed into not marrying Tejano men.) Divisions soon hardened, though, and from the turn of the century until the 1960s, Mexican-Americans found themselves increasingly disenfranchised, both from the land and the voting booth, with discriminatory practices keeping them from gaining a toehold in either arena.

The relevance of Ely’s treatment of race relations is matched by his care in exposing the harder truths behind the two pillars of West Texas’s identity: the rugged cowboy and the primacy of ranching. Racial and economic exploitation, dependence on the federal government, and man’s hardnosed defiance of environmental conditions –– these themes of agrarian and natural history lay at the roots of many contemporary conflicts. In that regard, Ely ultimately shows that Texas, long stuck in a tug-of-war of identity, is distinctly American.

Where the West Begins: Debating Texas Identity

By Glen Sample Ely

Texas Tech University Press

201 pps.

$34.95