In the sport of American football, violence sometimes begets more violence. I tackle you, you stiff-arm me, your teammate tries to block my buddy, who tries to shove him into both of us, the safety flies in over the top, and we all end up in a heap on the ground. Then we get back up, if we can, and we do it again.

In a recent column in The Guardian newspaper, a writer named Dave Bry suggested we not do it again. In fact, he prefers to go beyond a mere recommendation. He would have us walk off the field and never come back via a legislative ban on the entire sport.

The issue of football’s brutality has found itself much in the news in the past few years. A new Will Smith movie, “Concussion,” has propelled it even more deeply into the pop culture landscape. Bry’s piece, entitled “American football is too dangerous, and it should be abolished,” presents a balanced summary of many of the sport’s injury issues and some arguments for and against getting rid of it. At the end of the article, after determining the NFL won’t give up wearing helmets, he opines, “Which leaves us with one moral option: illegalize it, the whole operation.”

And then the column stops.

Bry didn’t present a vision for what the world would look like when the USA has banned football. It’s possible he just didn’t have the space, and that an upcoming column will detail his football-free future. I decided not to wait, however, because you can only properly evaluate a proposed policy if you consider how it will work once implemented. You don’t want to trade for Herschel Walker and then realize later he doesn’t really fit your offensive scheme.

Firstly, you’d have to think about how you might implement the proscription. Perhaps the Super PAC Mr. Bry founds will facilitate the election of enough anti-gridiron legislators to override the veto of, say, Patriots fan Bernie Sanders, Walker’s former New Jersey Generals boss Donald Trump, or Packers fan Gary Johnson.

Would compromises have to have been made to buy votes? Would existing football interests be able to capture the political process and turn it to their interests? For the sake of argument, let’s assume not. Let’s say the Anti-Touchdown League gets its own Volstead Act, no preceding constitutional amendment required.

So once you’ve gotten the bill passed, what do you do?

Well, there’s a lot of existing football equipment out there already that could be used by miscreants to continue to play the game. One would assume that you’d want to rid the country of those tools. Could you use a mandatory buyback scheme, like they did in 1996 with citizens’ guns in Australia? If so, how would the takings clause of the 5th Amendment require the government to compensate those from whom it took the pigskins, helmets, goalposts, shoulder pads, tackling dummies, and playbooks? You’d need to make sure you raised taxes or borrowed money to fund an appropriations bill for the FEA (Football Enforcement Administration) to pay for both the buyback and the enforcement of the ban. You’d also have to figure out if it were OK to repurpose, say, football cleats for other sports and a helmet as an unconventional flower vase or if that stuff all has to go to the incinerator.

You’d need to make a decision, too, on whether or not to permit entities like the Pro Football Hall of Fame to exist or the Texas Sports Hall of Fame to have football exhibits. You’d think today’s feds would frown on, say, a shrine dedicated to the interstate raw milk sales, imported haggis, or off-the-reservation gambling they prohibit. Do freedom of speech issues exist here? If so, you’d need to plot how you could get around them to keep people from glorying in the achievements of, say, George Preston Marshall.

In his column, Bry identified his most culpable culprits for the evil that is football. He writes, “The onus is on us, the fans (and, more directly, the team owners) who pay the players to hurt themselves for our enjoyment.” The ban on football companies would probably not be too different from scuttling breweries at the start of Prohibition. But if the much more numerous team fanbases bear the brunt of the blame here, restrictions to stop football fandom would seem crucial to the ban’s success. If you decide the Grambling Legends Hall of Fame’s tributes to the likes of Tank Younger and Doug Williams would allow football fans to continue being football fans, do those areas need to be replaced with boxing or CrossFit exhibits and should the memorabilia in question be burned?

While we’re on that subject, you’d need to plan for all the football writers, broadcasters, and bloggers you’d put out of business. Does the takings clause apply to their capital investments? And moving forward, are you allowed to write about football, or would that be giving material aid to the enemy? Might we need to shut down portions of that internet?

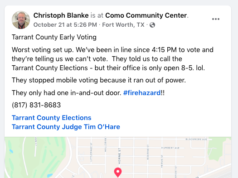

Moving on to enforcement, you’ll need to give the FEA sufficient powers to stamp out the vestiges of the sport. You’d need a training budget to ensure the gridiron gendarmes could recognize whether youths in the park were actually playing, say, rugby or whether they needed to spend a few days in juvy. For organized matches, is the referee sufficiently diligent in calling forward passes or is he letting a few too many go uncalled? You’d need to be very precise about what activities are and aren’t permitted in the presence of tackling. Perhaps this effort could double as a jobs program for the on-field officials who lost their jobs in the industry’s purge. You’d also want to add safeguards to ensure the authorities wouldn’t abuse the law, using it as a pretext to harass disfavored groups. After all, nearly 70 percent of NFL players are African-American.

You’d need to determine the criminal penalties to be visited on those die-hards who continued to block, tackle, and cheerlead in defiance of the ban. You’d have to somehow compute the damage caused to society or identifiable victims and make the prison sentences (and potential civil settlements) reflect those calculations. Would effective deterrence require some sort of three-strikes-and-you’re-out law for recidivistic touchdown celebrants (as I unashamedly mix sports metaphors)?

You’d have work to do internationally, too. The NFL has spent a lot of money marketing the game overseas. It’s not the biggest sport in the world, but it has a loyal following some places. You’d want to try pressure other countries into forbidding it as well and to negotiate treaties allowing extradition for Americans caught running fly patterns in, say, Moscow or Beijing. Canada’s likely to be a tough one here, as they have their own long football tradition. Might a wall along our northern border be needed to prevent our footballers from working illegally as Argonauts or Alouettes?

Once Mr. Bry has figured out the answers to all the points raised above, nobody will play American football anywhere in the world, apart, perhaps, from certain rogue lawless states. Somalia might become the world’s leading producer of linebackers.

Of course, you could have some bold commentators continue to address the issue of the football ban, couching it in terms of so-called “legitimate policy discussion.” What if you had someone write, for instance :

“The problem, of course, lies with some basic truths about human behavior. There is a strong demand for football in America. As long as those footballs are illegal, there will be great financial reward to anyone who can provide them.”

or

“The football trade has become as powerful a force in the Mexican economy as any legally sanctioned one. Powerful enough, it seems, to overwhelm any attempts the government might make at cracking down on the collateral effects.”

The phrases above came from a lucid author who puts words together very well. In one of his recent columns, he wrote about his “individualistic positions on . . . drug use (legalize it).” The passages above came from an article that same David Bry penned for BET, but I took some liberties with them. I substituted the word “football” whenever the word “drugs” occurred in the original.

You do have to try to anticipate collateral effects when banning stuff, for sure. Eliminating a violent black market is indeed among them. Would a football ban create a black market? How big would it be? Would the violence associated with such a market beget more violence than that which currently results from football? Would it create any additional unintended consequences? As Mr. Bry begins his campaign to eliminate American football, he will probably want to perform a thorough cost-benefit analysis.

Epilogue :

In another column, Mr. Bry called for a ban on dogs in New York City. My sister and I used to play football with our dog, Fuzzy, when we were kids, though not in NYC. We played tackle. My parents took home movies of it. If the U.S. implements the full Bry agenda, I may be in some trouble.