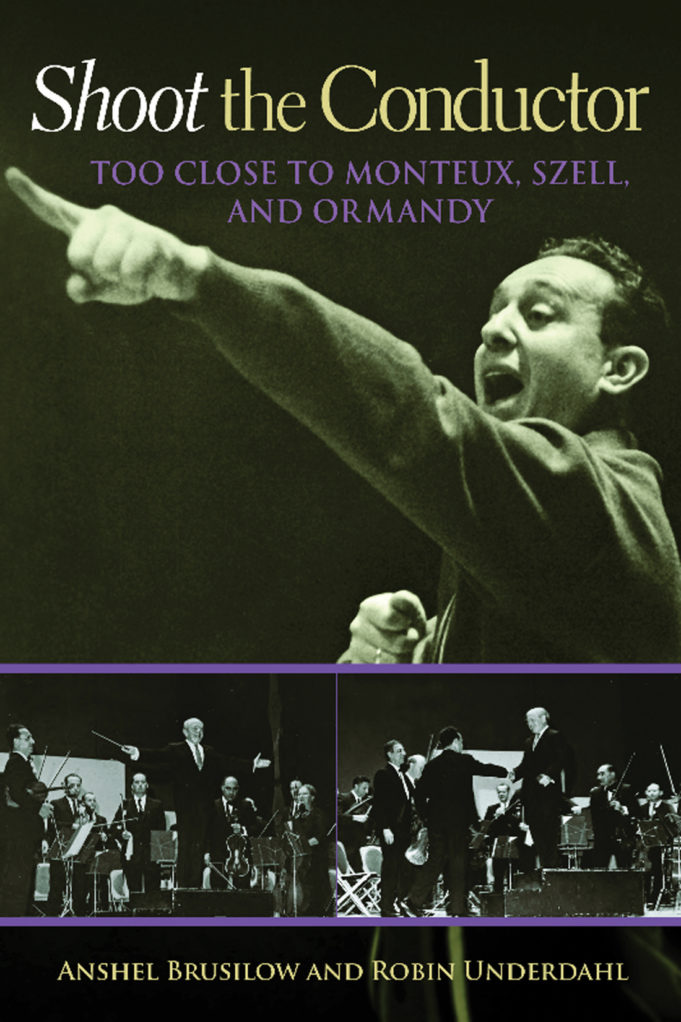

Famed conductor Anshel Brusilow first conceived of his memoir, Shoot the Conductor, in 1967. He didn’t start writing immediately. Life afforded the former conductor of the UNT Symphony Orchestra several more decades to ponder how he would tell his story as well as that of his musical colleagues. With the help of co-writer Robin Underdahl, his new autobiography, while dense at times, is as colorful and sensitive as the many orchestral recordings left by the artist.

By the end of first few pages, Brusilow sets the tone for the rest of the book. His writing is humorous and full of Dickensian characters. The year is 1933 in Philadelphia and 5-year-old Brusilow is meeting his first violin teacher, Edwin Fleisher. When a tall man in a dark suit asked his pupil if he would work hard at violin, the student recalled that he had no idea what that meant, but he knew the conversation would go better if he said yes.

The author’s vast memory emphasizes the historical importance of those he meets along the journey, but keeping up with the names of violinists and their teachers becomes a dizzying affair at points. Those dense moments are brief, though, and are more than livened up by dialogue and reminiscences by the young musician.

Brusilow’s parents, Leon and Dora Brusilovsky were musical Jews in current-day Ukraine. Leon was a violinist and Dora a pianist. The rise of Lenin came with increasing anti-Semitism, and the couple escaped to Ellis Island in 1922 while shortening their last name to Brusilow.

Shoot the Conductor is not simply a chronological recounting of one person’s life. Throughout his career, Brusilow came into contact with and befriended iconic performers and conductors like Eugene Ormandy, George Szell, and Pierre Monteux. With each meeting, Brusilow takes several pages or even an entire chapter to bring these now-deceased figures back to life.

It was Ormandy who gave the young violinist the position of concertmaster for the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1959. During the first rehearsal, Brusilow was overwhelmed. It was the sound, a lush sound like no other orchestra, now vibrating all around him.

For students of conducting or music history in general, the recollections of Ormandy and others richly cover the profound to the banal. And it all serves to immerse the reader in that long-ago time.

“Ormandy had a way of communicating with us as a body so that we had a sense of communicating with each other too,” Brusilow writes. “There was less micromanagement of the players” than with other conductors.

And then there are the recollections of Igor Stravinsky, possibly the most influential composer of the 20th century. In the spring of 1964, the 37-year-old conductor met the great master at the May Festival in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Previously content to ask for an autograph, Brusilow struck up the courage to discuss conducting with the infamous composer of “The Right of Spring.” Stravinsky used the conversation to rail against rogue conductors who oversimplified his complex rhythms and time signatures. Brusilow took the message to heart and vowed to honor the Russian composer’s original manuscript from that day on.

But that same passage is an example of the writer’s willingness to blend the profound with the downright irreverent (but funny). Quite simply, the conversation ends with a potty joke. What often gets lost in the humorous prose is the hard fact that a long life typically offers periodic tragedy, such as the time Brusilow was nearly raped as a boy. Heartrending events pepper the writing every other chapter or so. Numerous disappointments that befell his mentors when Brusilow abandoned his violin for the podium could not have been easy passages to write.

In the end, Brusilow’s memoir has little sex appeal. There was never a scandal that beset the conductor that would entice gossip vultures to dive into the memoir for goodies. Shoot the Conductor is not a cathartic attempt by the author to justify his or her life or play up the over-romanticized American zeitgeist of what a suffering classical musician is or should be.

Brusilow is simply telling the story of a Jewish son of immigrants journeying through life. The fact that his life involved many of our most treasured musicians, composers, and conductors makes the ride all the more pleasurable.

Disaster that happened in Kuwait when Iraq started war on their soil due to which Indian Government had to rescue more than 1.70,000 people is never know to anyone. But now a movie is about to release about the same by the name Airlift movie for more info you can view at http://www.airliftmovieonline.com and BTW nice article 🙂

keep smiling