This past Tuesday morning was like any other at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. A few visitors were trickling in to see That Day, an exhibit of 27 black-and-white and color photographs by photojournalist Laura Wilson that just opened and will be up until February 14, 2016.

Five stories below, Jana Hill and Emily Olson had their game faces on, painstakingly digitizing photographs and negatives to upload them to cartermuseum.org. With help from Olson, a recent TCU grad who just received a federal grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Amon Carter digital media specialist Hill has been through 22,000 photos and several thousand negatives so far.

She’s got only about 185,000 negatives to go.

“Our department has evolved to be the conduit between our collections and the public,” Hill said. “We do a lot of behind-the-scenes things, but we’re doing it with the public and scholars in mind. We are more user-centered-approach than … in the past.”

The Amon Carter possesses one of the largest repositories of its kind in the country. But what good are photos if nobody sees them? The museum’s efforts to make its archives available online is part of a larger movement toward “open content,” Hill said.

“There used to be an attitude that if you kept art more private and didn’t share it, somehow the works would be intrinsically more special, but that’s been disproved,” she said. “Industry-wide, there is a trend toward making things more available.”

Carter staffers are “thrilled to bring the work of these eight photographers to the public in a meaningful way, particularly since many of the works are too fragile for exhibition,” said Tracy Hill, Amon Carter public information officer. “By offering new insights into the lives of these eight artists and providing context for their work, we hope this material will serve as an important educational resource for students, teachers, and scholars in the humanities.”

Getty Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands, the Carter began digitizing its archives in the early 1990s, but the effort to make them public began earlier this year. That’s when the museum joined the American Art Collaborative, a consortium of 14 U.S. museums committed to making its art collections viewable online. The Dallas Museum of Art is also a member.

The Carter has been able to digitize its archives through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities that matched the museum’s own financial support for the project, Hill said.

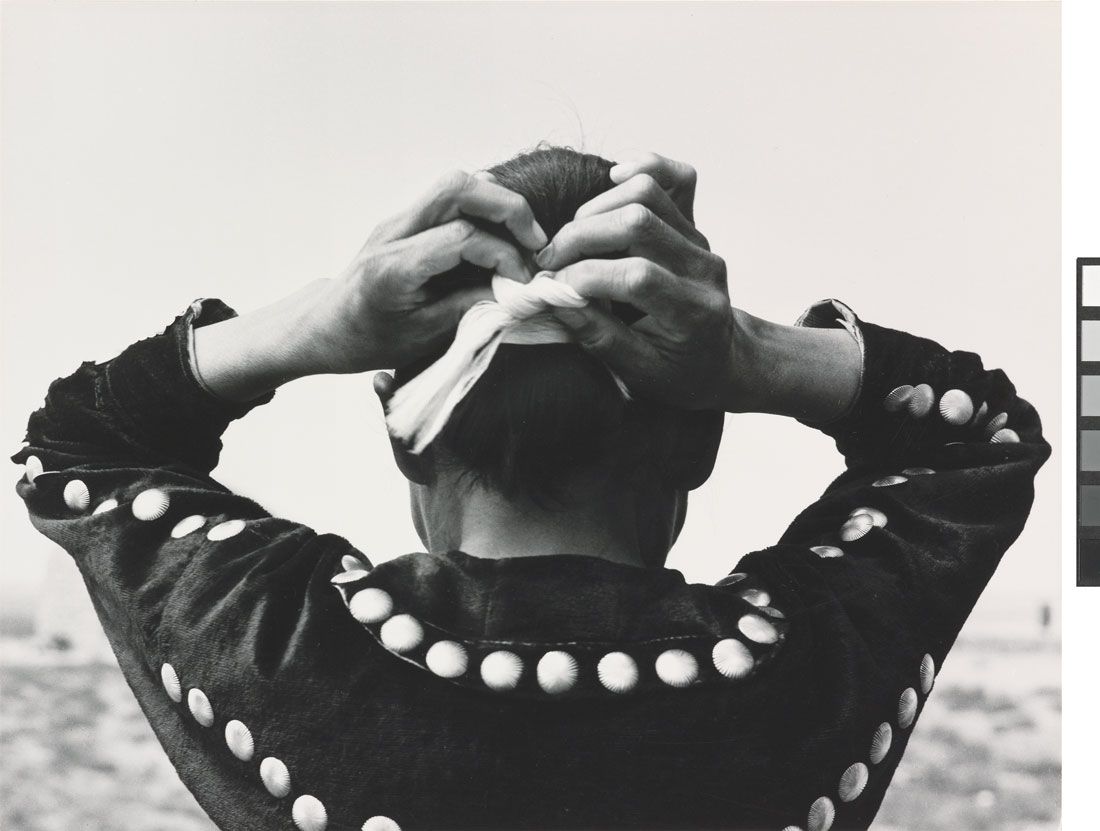

The Carter’s love affair with photography dates back to the building’s opening in 1961. Created to document the museum’s history, the archives now include the photographic estates of eight prominent photographers: Carlotta Corpron, Nell Dorr, Laura Gilpin, Eliot Porter, Helen Post, Clara Sipprell, Erwin E. Smith, and Karl Struss. Each collection was bequeathed to the Carter upon the artist’s death, beginning in 1979 with Gilpin.

In addition to personal relationships, each artist exhibited at or had a photobook published through the museum. The oldest photos date back to 1905 and belong to Gilpin, Sipprell, Smith, and Struss individually.

The most unusual parts of the collection, and the most sought after by the public, include nitrate negatives, glass negatives, and autochromes.

“They are particularly interesting because they are unique images, and so few have survived the decades due to their fragility,” Greene said.

Based on public interest and information requests, the most popular areas of the archives are Smith’s cowboy photographs from the early 20th century, Porter’s color nature photographs, and Gilpin’s Navajo photos.

The archive sits in storage rooms that were constructed during a 2001 renovation. The “cool” room holds the bulk of the black-and-white photos. A lot of them find their way to the galleries above, mainly to dovetail with or piggyback on themed exhibits.

The “cold” room, which is bitterly cold, holds the Carter’s color photographs and tens of thousands of negatives.

“The cold preserves the color from fading over time,” Hill said. “At 20 degrees, the temperature provides a more stable environment [which] slows down color shifts. Nitrate negatives are kept in a separate freezer because of the explosion hazard.”

There isn’t sign of frost or ice in the 20-by-20-foot room. That’s because the air is maintained at zero humidity.

But the collection tells only half the story of the men and women who pioneered photography as an artform while documenting America’s early history. The archive also contains photographic ephemera: letters, journals, and mementos, all under the care of Amon Carter archivist Jon Frembling.

“We want the patrons to be able to put these artists in the context of time and place,” he said.

On a recent morning, Frembling dived into Gilpin’s effects and retrieved a beautifully shot black-and-white image of an outdoor scene with a dozen men and women congregating around one man.

“Here she is at The Aspen Institute lectures, which leads to the creation of Aperture Magazine,” Frembling said. “There’s Eliot Porter, Ansel Adams [the man in the middle], Dorothea Lang. This is like a who’s who in that period of photography, and she is the one who documented it.”

The image is an example of how artists create — in a community, he added.

Frembling then flipped through one of Gilpin’s personal scrapbooks. Carefully taped to each page was a montage of invitations, letters, and newspaper clippings.

“Seeing things like this allows you to get to know the artist as a person and not just the person who created this output,” he said. “You get to know them and what it is they are creating, the how and why they are creating.”

Frembling does not expect any bequests in the future, but if one does happen, it will definitely be the result of an existing relationship between the Amon Carter and the artists.

“Art’s great by itself, but it’s even better when you have the whole story,” he said.