For a small regional company with a modest budget, Texas Ballet Theater rarely ceases to amaze, producing performances that are grand and memorable. Since artistic director Ben Stevenson took over 10 years ago, bringing with him a wealth of full-length story ballets from his years leading the Houston Ballet, the company has excelled in opulent, classical spectacle.

But once a season the company sheds the finery to present the dancers in shorter, modern repertory. This year’s program, which opened earlier in Fort Worth and closed last weekend in Dallas, had no classical pas de deux or other frills. Instead, the focus in Fort Worth was on three substantial ballets from the last 75 years: George Balanchine’s Serenade, Stevenson’s L, and Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s Gloria. (In Dallas, a new piece by company principal dancer Carl Coomer, Clann, replaced Gloria.) The entire evening was beautiful.

TBT had presented Serenade before, and it’s a great piece for dancers as well as the audience. Balanchine created the ballet in the 1930s for his fledgling School of American Ballet, then a disparate group of young dancers he was pulling together into a professional company. The piece is a study in ensemble dancing, a wonderful tool for any company.

In Fort Worth the curtain went up on a bare stage and 16 ballerinas in filmy knee-length skirts standing well apart in diagonal rows facing downstage right. Their right arms were raised, and the backs of their hands shielded their eyes from a bright light. They stood motionless as the majestic opening of Tchaikovsky’s “Serenade for Strings” began, and then, at the same time, to the same height, their arms raised and slowly fell. There followed a kaleidoscope of synchronized movement to the end of the ballet. The magic is that it all translates into a stunning visual realization of the score, not just an exercise for the dancers.

To showcase the men, Stevenson revived L, a thank-you choreographed for Liza Minnelli after a benefit concert she gave for the Washington National Ballet when he worked there back in the 1970s. The ballet featured three percussionists from the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra (everything else was prerecorded): John Bryant, Drew Ferraro, and Drew Lang played marimba, kettle drum, and just about everything in between.

Eleven men in black shirts and trousers danced jazz, blues, and boogaloo in different combinations, but the kicker was the furious finale. Each dancer came racing on stage one after the other to show off his particular skills: leaps with leg splits front or side, straight up or sideways jumps with turns, turns onstage, anything you can think of in athletic dancing at top speed, bringing the crowd to its feet screaming before the piece was over.

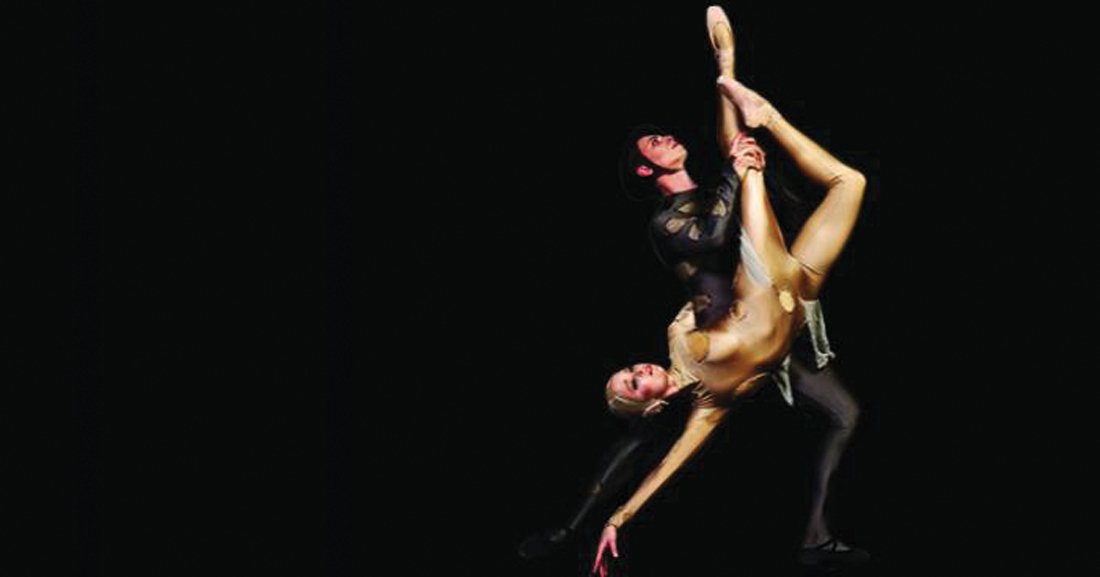

In a dramatic change of mood, Gloria ended the evening on a sober note. Created as an homage to those who suffered in Europe during World War I, the piece employs Francis Poulenc’s gentle “Gloria in G” as a musical backdrop. Midway upstage, an uneven hill dominated the scene. Soldiers in brown or gray uniforms with round, flat metal helmets staggered across the stage. Two women in white with round clusters of braids covering their ears floated through the crowd: Leticia Oliveira as a fearless fighter and Carolyn Judson a woman in mourning. In one startling moment, Oliveira and two soldiers were raised up with arms extended to create a memorable crucifixion tableau. MacMillan’s innovative choreographic touches in lifts and movement give the ballet added dimension. In the end it becomes not just about WWI but the horrors and suffering of all war.