What we farm, hunt, buy, catch, kill, package, heat up, cook, serve, and enjoy privately or among others is merely a jumping-off point for Art and Appetite: American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine. The 60-piece touring show, up through May at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, touches on issues of class, race, gender, religion, and painting itself, spanning the genres of neoclassicism, high modernism, and contemporary art. And it’s a real, um, treat.

The exhibit provides a hearty appe-tizer at the entrance. Roy Lichtenstein’s “Turkey,” Doris Lee’s “Thanksgiving,” and Alice Neel’s “Thanksgiving” flank Normal Rockwell’s iconic “Freedom from Want.” Painted at the height of World War II, when rationing was de rigueur, the 46-by-35-inch piece — of a very white family being served a turkey dinner by an even whiter Grandma and Grandpa — works on a couple of different levels. Along with whetting the viewer’s appetite for more spectacular art, “Freedom from Want” also lets him or her know that Art and Appetite is no ordinary touring show. It’s quite a blockbuster.

Unfolding in mostly chronological order, the exhibit proper opens with several amusing 18th-century pieces. The tastiest one is John Greenwood’s “Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam.” Nearly two dozen tricorn-wearing dandies in powdered wigs and white stockings are partying like madmen in a pub or inn, dancing, smoking, sitting at tables and talking, drinking beer from bowls (the day’s preferred beer conveyance), puking, and, in one instance, pouring beer on the head of a guy passed out in a chair. Some of the men are smiling, but most of them look pretty haggard, underlining Greenwood’s point: temperance, my friends, temperance.

The show is loaded with easily identifiable characters or types, allowing the artists to comment on social phenomena of the day, including the evolution of dining from formality to celebration to afterthought to all that it is today. In the late 19th century, breaking bread together could be celebratory and casual — the bourgeois family that has gathered outdoors for some grub in Thomas Cole’s “A Pic-Nic Party” (1846) looks to be having a ball. The characters in “The Epicure” nearby aren’t nearly as enthusiastic. Francis W. Edmund’s warm-toned 1838 painting revolves around a well-dressed gourmand as he contemplates buying a suckling pig from a plain man and plain woman in a plain shop. The gentleman, with his girth and finery (and snuff box), represents Northern banking interests and swallows the scenery in contrast to the slender, brown simplicity of the farmer, his wife, and their meager, traditionally Southern offering.

In the 18th and 19th centuries in this country, class distinctions seemed to be changing constantly (and not always for the better). Some of the paintings serve as documentation of the socially volatile times. The thorough wall texts are indispensible. The sitter in John Singer Copley’s portrait “Mrs. Ezekiel Goldthwait/Lewis” looks like any other middle-aged matron, but as the wall text informs us, she was actually a prosperous gardener — the fresh-looking peaches, apples, and a pear piled in a bowl on a table next to her symbolize the source and extent of her wealth. And her fecundity. She had 13 kids.

From still life, easily the most popular medium for food-related visual themes, the jump to trompe l’oeil seems natural. Hyper-realistic paintings with a three-dimensional feel were highly subversive in the 19th century — and were occasionally fraught with violent implications. In the 1880s, the Irish were personae non grata in polite society, and De Scott Evans either endorses or criticizes their outsider status in “The Irish Question.” A trompe l’oeil painting of two potatoes hanging against a wooden panel by two strings that look a lot like nooses, the piece cheekily references the tradition of pub owners hanging in their front windows trompe l’oeil paintings of dead animals to indicate, “No Irish allowed.”

As food culture changed over the decades — from intimate and family-related to societal to finally industrialized, commodified, and over-advertised — art also transformed, both conceptually and in terms of form.

Among several other juicy conversations between pairs of paintings in Art and Appetite, the most delicious is between Edward Hopper’s legendary “Nighthawks” and Archibald John Motley Jr.’s “Nightlife.” Motley created his colorful, jazzy mise-en-scène of a jumpin’ Chicago nightclub after seeing Hopper’s desolate diner piece and thinking, “How sad.” Though WWII was hovering over everyone’s heads, Motley chose to focus on the release rather than the tension.

In playing nicely off still lifes, abstraction seemed ideally suited for food imagery. Gerald Murphy’s “Cocktail” (1927), a cubist rendering of a martini glass, lemon, and shaker, is a dynamo of angles, subdued radiance, and international flavor. Stuart Davis’ “Super Table” (1925), a delirious, hyper-flat, nearly monochromatic painting of a table, goblet, and notebook (opened to a gridded drawing of a female nude), is warped, a kind of still-life as designed by an advertising agency.

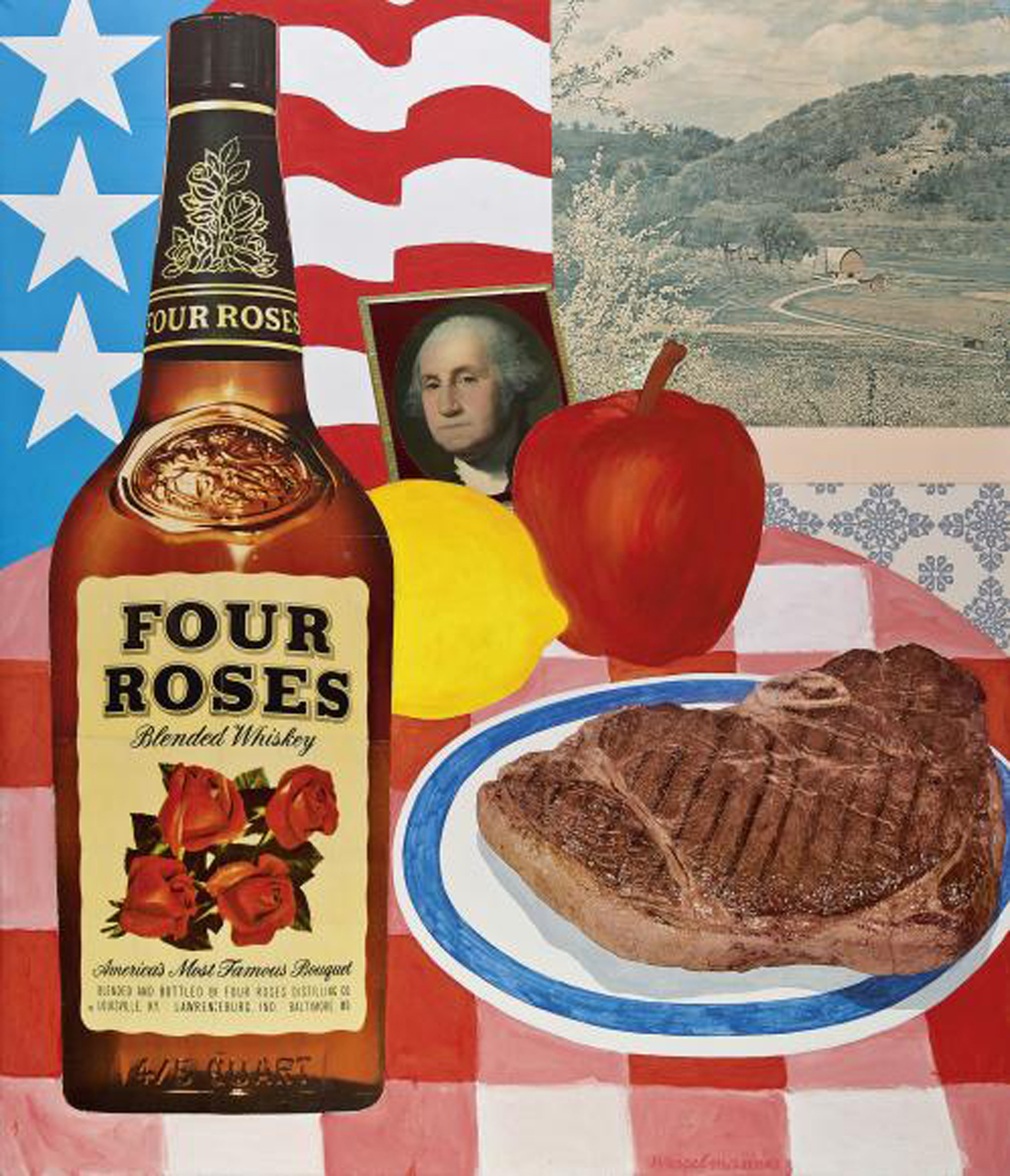

Somewhat like food, art seemed to reach its apotheosis in the 1960s — everything had already been done. Well, just about everything. There’s nothing like Claes Oldenburg’s wedding souvenirs: lifelike sculptures of slices of white wedding cake created for a real wedding in California in 1966. Another nimble commentary on mass production is Wayne Thiebaud’s “Salads, Sandwiches, and Dessert,” a lightly colored array of the titular items arranged in neat cafeteria-style rows. Easily the most uproarious pieces at the Carter are two ’60s-era Tom Wesselmanns. “Still Life No. 15” pairs several photos — of a bottle of Four Roses “blended whiskey,” a sprawling cooked steak, a bucolic countryside, and a portrait of George Washington –– with crude paintings of an American flag motif, a lemon, and an apple. In “Still Life No. 14,” cutouts of a loaf of bread, bananas, a glass of Coca-Cola, and two Ballantine beers rest on a blue table backdropped by an eye-popping red cabinet emblazoned with a Mondrian painting on one side and, above the sink, a white star.

Aside from Andy Warhol, whose lone contribution to Art and Appetite is a blue Campbell’s soup can, the biggest name in Pop-Art was Lichtenstein, who is also represented by “Standing Rib (Meat),” a detached, cartoonish, and succinct chunk of tight, clean black lines and bright red fields. It’s in the same lighthearted spirit of his other offering, the one near the entrance, the one next to Neel’s portrait of a raw turkey lying in a kitchen sink.

[box_info]

Art and Appetite: American Painting, Culture, and Cuisine

Thru May 18 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd, FW. Free. 817-738-1933.

[/box_info]