When he finally returned home, Mahmoud Alafyouny’s life fell into a predictable routine. During the days, he held down a job at a North Texas tire store. During the evenings and days off, he tackled a honey-do list that had grown long during his absence. The yard at his home in Mesquite needed tending. The swimming pool in which his stepchildren played needed repair. The garbage disposal was on the fritz. Then there was the woman he loved, Rae. They had seen each other for short periods of time when she came to visit, but the couple had spent no real time together for more than two years.

Friday night two weeks ago, they spent the evening at home, watching a movie Rae got from Netflix. Neither of them heard the telephone when it rang, and they didn’t hear the ominous message until they were getting ready for bed.

Friday night two weeks ago, they spent the evening at home, watching a movie Rae got from Netflix. Neither of them heard the telephone when it rang, and they didn’t hear the ominous message until they were getting ready for bed.

The call was from an Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent. The device that monitored the location of the bracelet locked on Alafyouny’s ankle had gone haywire, the agent said, and Alafyouny needed to come to immigration headquarters in Dallas to pick up a new one. On Saturday morning, the Alafyounys did as they had been instructed. But instead of being given a new box, the agents led Alafyouny into a back room and told his wife to wait.

“A few minutes later, a lady came out and told me that were taking him back into custody for deportation,” Rae said. “They didn’t say a thing about the box.” They did, however, stick to their threat to deport him. Late last week, after losing a years-long court fight to remain in the United States with his American-born wife and her five children, Alafyouny was forcibly returned to a uncertain future in Jordan.

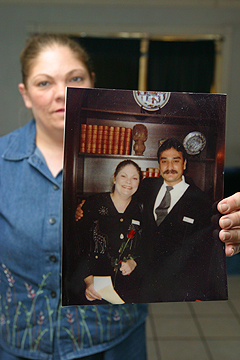

The strange case against Alafyouny, first reported last year by Fort Worth Weekly and later the subject of a CBS Evening News segment, is based, as far as anyone outside the government can tell, on a single, questionable, decades-old accusation.

When he came to the United States 10 years ago, Alafyouny applied for political asylum, lost, and was placed in deportation proceedings after volunteering the fact that he had collected small amounts of money for the Palestinian Liberation Organization more than 20 years ago as a teenager on the streets of Jordan. Under the USA PATRIOT act, the law Congress rushed to pass following the 9/11 attacks, that admission legally transformed Alafyouny into a deportable “alien who engaged in terrorist activities.”

Although the PLO was never officially designated a terrorist group, federal officials contend it has sponsored terrorist acts and that anyone who raised money for it would know that. The government’s interpretation of the law, however, has increasingly come under attack.

Alafyouny, his wife, and their lawyers have long maintained that Alafyouny posed no danger to anyone in the U.S. Now, they have gained the support of a former federal official and a Middle East scholar who also are challenging the government’s case.

In court papers filed in Alafyouny’s failed appeals, Philip C. Wilcox said Alafyouny’s fundraising and pamphleteering for the PLO “were benign political acts that should not be regarded as engaging in terrorist activity.” Wilcox’s credentials? During the time Alafyouny was collecting donations for the PLO, the former U.S. ambassador at large and counter-terrorism coordinator served as the State Department’s director of Israeli and Arab-Israeli affairs in the Bureau of Eastern and South Asian Affairs.

“It would have been normal for a young Palestinian in Jordan at that time to engage in such fundraising for the PLO as an act of patriotism and loyalty to the Palestinian community, without expecting that the funds would be used for violent activities,” Wilcox wrote in a June 11, 2006, letter written on Alafyouny’s behalf.

Additionally, a California scholar who is past president of the Middle East Studies Association said the government’s contention that collecting money for the PLO amounts to a terrorist act is at odds with history. The government is “projecting the current post-9/11 period onto a very different, earlier historical period in the Middle East,” University of Southern California professor Laurie Brand said.

“If all those who engaged in the same kinds of activities for which Mr. Alafyouny is now being charged with having supported terrorism were to be called to account in the same way, the vast majority of Palestinian businessmen, academics, lawyers, engineers and peace activists today would have to be put in the same category,” she said in an affidavit given earlier this year.

Another unexplained oddity about Alafyouny’s case arises from his wife’s job. Rae works as a security screener at Dallas’ Love Field for the Transportation Security Administration, which, like the immigration agency that branded her husband with terror accusations and deported him, is part of the Department of Homeland Security. If Alafyouny is the dangerous person that ICE contends he is, no one has explained why someone married to him would be allowed to work in such a sensitive position. TSA officials have said Rae is a model employee. And on the day that her husband arrived back in Jordan, Rae was working at the airport, trying to keep the bad guys with bombs off airplanes.

“I work on a job every day … fighting terrorism myself,” she said. “The organization I work for trusts my judgment, but the INS doesn’t trust my judgment? They’re obsessed with deporting people for any reason because it makes them look better.”

ICE confirmed last week that Alafyouny had been deported, but immigration officials did not respond to other questions about his case.

Alafyouny was first locked up in 2004 after losing an early appeal of his deportation order. He spent more than two years in detention in a West Texas prison. After the government lost a round in Alafyouny’s protracted legal fight, immigration officials agreed to release him while his case moved through the courts. But when he lost an appeal before the U.S. Fifth Circuit, they moved to pick him up again.

Alafyouny, who spoke freely about his case with the Weekly when he was behind bars, refused to talk about anything after he was released. His wife and lawyers also went mute.

But when her husband was again jailed, Rae broke her silence and disclosed that the government, in addition to requiring Alafyouny to wear an ankle monitor, also had forbidden him to speak about the case while he was free. “We were not to talk to the press,” she said. “I was never given a reason by anybody. I’m assuming it was just because they didn’t want any media attention.”

Rae isn’t sure what happens next. Her husband’s family in Jordan let her know that he had arrived safely, but she wasn’t able to speak to him for several days. On Monday, she said she had finally spoken to him, and that he is living with his mother for now. His legal situation in Jordan is uncertain: Officials there are holding his passport until he has been interviewed by Interpol. The couple is going to try to obtain permission for him to return the U.S. If that fails, as it likely will, Rae said she may move to Canada, because she believes that the government there may allow her husband to immigrate to that country.

Before the government took her husband away, one of the last things the Alafyounys did was buy a garbage disposal on eBay to replace the broken one in their kitchen. Today, the home repair project has become a symbol for a family torn apart. “It arrived,” she said, “but now there’s nobody to put it in.”

“I don’t know what possesses them to destroy someone’s life over nothing,” she said.

North Texas journalist — and former Weekly staffer — Dan Malone can be reached at danmalone@earthlink.net.