The dispute between Mercy Culture Church and its Northside neighbors over the church’s plans to build a living facility for human trafficking victims is now in the hands of Fort Worth City Council.

Councilmembers are expected to consider the issue at their zoning hearing tomorrow (Tuesday, Dec 10).

Located next to the church, the proposed Justice Residences are a “long-term restoration home for up to 100 survivors of human trafficking in the United States,” according to the church’s Justice Reform website. “Justice Reform” may sound like something to do with improving the country’s broken legal system, but in this context, it’s an anti-human trafficking nonprofit. Founder, Mercy Culture pastor, and “lead reformer” Heather Schott claims that though human trafficking is a huge issue, there aren’t many locations for survivors to seek refuge, hence the need for the residences.

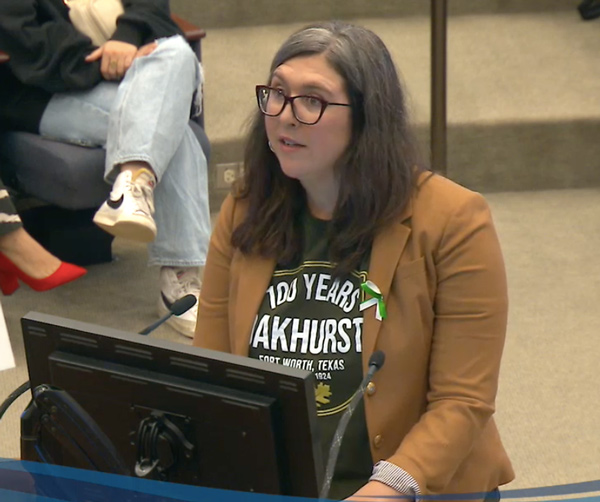

Residents of nearby Oakhurst agree in theory but believe their neighborhood near the intersection of N I-35W and Oakhurst Scenic Drive is not the appropriate locale. Residents previously voted against the plan, and more than 300 of them signed a petition opposing it as well. Katherine Bauer of the Oakhurst Neighborhood Association argued that the location of the facility is inappropriate, mainly because of already existing traffic and parking issues stemming from the church.

During a Zoning Commission meeting last month, Bauer said, “There is simply not enough room to add anything additional to this property, much less a 43,000-square-foot building with a 100-bed residential component.”

Schott, who runs Mercy Culture with husband Pastor Landon Schott, is onto a real issue.

“The majority of the women rescued have no place to go and end up back in the streets being re-trafficked,” Schott said during the Zoning Commission meeting.

The National Library of Medicine says that in 2019 Texas ranked second in highest reported human trafficking cases, likely because of our state’s sizable and diverse population and long international border. In a 2024 study about the housing needs of human trafficking survivors, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development identifies “scarcity of crisis and shelter resources” as a barrier for victims to receive services: “Survivors can access many types of housing resources and services, but the primary constraint of survivor-specific programs, the homeless assistance system, and general affordable housing programs is that there are not enough resources to serve everyone who could benefit.”

The report also stresses the need for “trauma-informed and survivor-centered practices, culturally specific services” as well as “wraparound supportive services tailored to each survivor’s needs and circumstances.”

It’s not clear if that would be provided at the Justice Residences since the main purpose of the facility is said to be spiritual and religious restoration. In fact, “meeting the physical needs” of the survivors was described as a “secondary goal” in a public slideshow presentation by the Schotts’ lawyer, Kyle Fonville.

While anyone can be a victim of human trafficking, not everyone is, and there are some people who are more vulnerable to this harm than others. This includes members of the LGBTQ+ community, but judging from Mercy Culture’s previous stances against gay and transgender people, it’s unclear whether queer victims would be welcome at the Justice Residences.

Heather Schott did not reply to our requests for comment.

During the Zoning Commission meeting, Mercy Culture Church and the Oakhurst neighbors were able to argue their cases for 15 minutes each. Both sides brought up lawyers and Regular Joes to speak. Human trafficking experts and survivors were absent from the discussion. The exception may have been one woman, who was the last of the church’s supporters to testify, but as she was describing her experience in a violent situation, her time ran out before she could finish.

Fonville made it clear that his clients are not considering an alternative location for the Justice Residences. He said 18 parking spaces would be added to the site for a total of 661, based on the building’s site plan attached to the council agenda. Fonville also had a somewhat flippant response to the neighbors’ concerns.

“The parking issue is no different than if you go down to TCU football stadium,” Fonville said to a Zoning Commission member. “There’s no parking there. You’re either going to walk miles to get to the stadium, or you’re going to pay $50 to park in somebody’s lawn, which is what I did the other day. The City of Fort Worth doesn’t tell TCU to stop playing football games.”

The neighbors and church supporters also debated whether bringing in the Justice Residences would be safe and if such a facility meets the planned development zoning definition of “church-related.” A Fort Worth police spokesperson said their department has not been involved in security planning for the residences but could offer off-duty or part-time job opportunities if requested. Ultimately, the Zoning Commission narrowly sided with the neighbors in a 6-4 vote to deny, but City Council will have the final say.

Fonville claimed to have “unity” with the city and support from councilmember Jeanette Martinez.

Courtesy YouTube