Long, long ago (the mid 2000s) at a house party far, far away (Denton), two young dudes who loved comic books came up with an idea for a story. It wasn’t some left-turn take on some obscure, throwaway IP they liked when they were kids. Nor was it some new way to tell the tale of Night of the Living Dead, The Odyssey, or the events depicted in Amazing Fantasy No. 15. Instead, the idea was “the stages of grief personified,” a heavy subject for a couple of 18-year-olds crushing beers in a backyard.

The two dudes having this conversation were Andrew Calvert and Scott Prather, who were then students at UNT. Calvert majored in creative writing and marketing while Prather was an art student. They were hanging out at the house of a mutual friend, Fort Worth painter Jay Wilkinson, whose place was “like the central party house,” tattoo artist Prather said from his studio alongside Calvert, “and that brought in a lot of people, and that’s where I met [Calvert] and found out we both had a love for comics.”

Prather doesn’t recall how they came to talk about his heavy notion for a comic book story, only that they were captivated by a marketing campaign for the latest Batman movie at the time. “I think [the idea] started off like this alternate-reality game, because at the time, The Dark Knight was coming out, or the [third] one, right?”

“They had a marketing campaign that was interactive,” Calvert said. “There was this scavenger hunt at a mall in Dallas. We showed up, and there were like 50 people in this mall, and we were calling [Prather] — this was before anyone had iPhones, really — and he was at home where there was internet connection. He’d be like, ‘Go right, and don’t step on a banana.’ And there’d be the Banana Republic, so you’re solving these puzzles.”

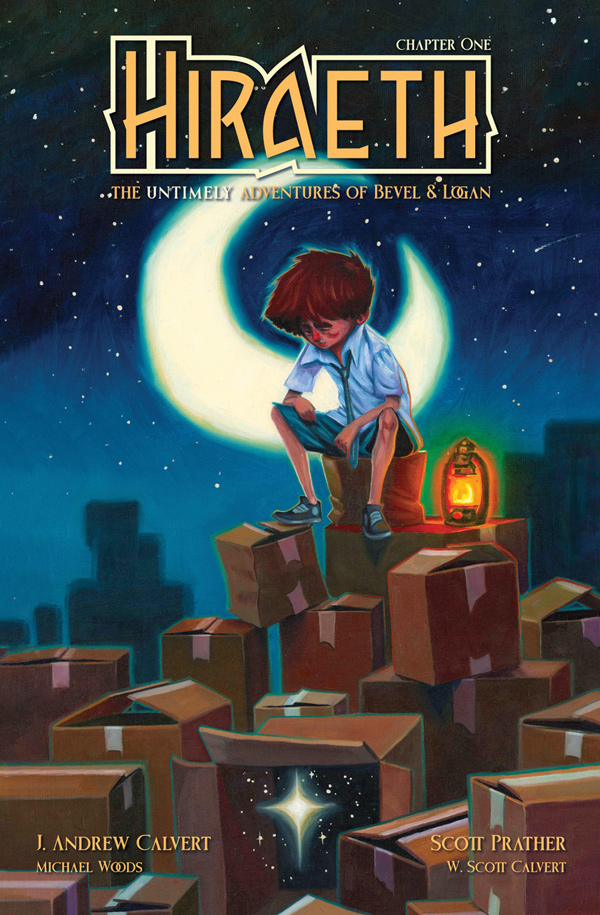

Probably for the best, most ideas generated by 18-year-olds in the vicinity of a keg and handles of Jim Beam never become reality, but Calvert and Prather’s party talk and cooperative puzzle solutions for a fictional-world-within-a-world would actually become a real-life quest: Creating and publishing their own comic book, geared toward kids and based on Prather’s idea about the stages of grief, set in a hidden, fantastical realm, like Narnia or the Secret World of Og. While their path wasn’t exactly perilous, it was littered with obstacles and restarts, as well as the sort of good fortune that makes protagonists rise above the odds, such that on Wednesday, Nov. 13, the two creators will finally put out the physical copies of the first issue of Hiraeth, The Untimely Adventures of Bevel and Logan, their 19-page full-color comic that is as professional as anything you’d find on a shelf at your local shop.

“That’s why we tell stories,” reads the book’s second-to-last page. “They’re the tools we use to remember. To remember the things we’ve lost. To remember the things that matter most.”

Courtesy the artists

******

Calvert got into comics when he was a preteen, reading whatever books featured Daredevil, Spider-Man, and the X-Men, but the comics that have influenced his writing the most came later when he was in high school and after he finished college: Warren Ellis and John Cassaday’s Planetary and Y: The Last Man by Brian K. Vaughn and Pia Guerrera, plus “anything” by Brian Michael Bendis.

“Those books really shaped my tastes and opened my eyes to what the medium could do,” Calvert said.

A fan of serialized drama — there are few things Calvert likes to discuss more than ABC’s Lost — Calvert really got to work on his chops with Hiraeth, seeing as how his and Prather’s creation has existed in multiple unfinished forms since way back when.

“I think I wrote the first draft of the whole series in 2011,” Calvert said. According to him and Prather, they’ve mostly maintained that storyline all these years.

Prather said Calvert has rewritten it “like three times.”

Prather, who left UNT after a year and finished his degree at Ringling Bros. College of Art and Design in Sarasota, Florida, wanted to use Calvert’s draft for a capstone project. “I thought, ‘I’m gonna use this as my senior thesis,’ and when that came around, I was like, ‘I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing.’ ”

Calvert next rewrote his treatment as a children’s book with Prather illustrating it.

“It was long prose with pictures,” Prather said, “and that wasn’t really hitting it, either.”

Calvert kept refining his story, and in the meantime, he and Prather found themselves in careers — Calvert works as an operations manager at BNSF railroad, and Prather is a full-time tattoo artist with his own studio. Making a comic book was still a thing they talked about, but for various reasons, the timing hadn’t yet fallen into place. Prather’s interest in comics had waned into casual territory over the years, and he occupied himself with other pursuits, primarily tattooing and partying. But when he quit drinking and moved from a tattoo shop to his own by-appointment place, he started picking up comics and studying their form once more. “When I felt comfortable in my [tattooing] career, and I had gotten sober, in 2021, [Calvert] and I kind of reinvigorated our love of comics.”

As their attention to the medium reignited, so did their drive to make their book. In the summer of 2022, they sat down and “got the gist of the story,” Prather said. Around the same time, Prather met artist Tony Harris at the Dallas Fan Expo. Harris broke out as a household name in 1994 with his stint drawing Starman for DC Comics, for which he would earn an Eisner award in 1997. Starman was one of Prather’s favorite comics as a kid, and he was able to channel his fanboy enthusiasm into an offer to tattoo Harris in exchange for letting him and Calvert ask him about creating comics. Soon, Prather and Calvert were making the 14-hour drive to tattoo Harris at his home studio near Macon, Georgia.

At that point, the two had planned to do their story as a graphic novel.

“And [Harris] was like, ‘No, don’t do that,’ ” Prather recalled. “He told us we should do it as individual issues. That way, our names would be out there more.”

“We came back and revamped the script again when individual issues became the format,” Calvert said.

Harris also critiqued their method, Calvert said, pointing out “some errors in our creative process. Initially, [Prather] wanted free reign as far as panel design and what he wanted to do with the artwork, so I tried to write toward that. And [Harris] was like, ‘No, the way you’re writing this is inhibiting him.’ ”

Courtesy the artists

Harris took them through the artistic process he goes through with his writers.

“He pulled out a bunch of prelims and scripts and stuff, and he kind of gave us a big fun crash course,” Calvert said. “He read through our script and pointed out what wasn’t working and what ultimately inhibited the artist. We kind of realized that writer-brain and artist-brain are totally different things.

“The way we were doing it, there were too many options, so that upped my writing game by figuring out which gestures were the most important, where to place those things, and after that, we really started gelling.”

Prather started drawing the book in earnest in 2023, and in the way he and Calvert had to learn that specific is better than general when it comes to plotting sequential art, Prather had to learn to make his own work more efficient. At the start, he wanted to have physical art he could keep, and he was trying to draw like his heroes rather than to his own strengths.

“I was drawing in large format and emulating people I liked,” Prather remembered, “so I drew 17 pages. I’d sketch out the whole page and then draw the whole page. And then do that for the next page. And so it was a very clunky way to go, and I didn’t know what the next page looked like. And then I tattooed another comic book artist, Martin Simmonds, down in Austin, and that changed everything.”

Simmonds worked with one of Calvert’s favorite writers, James Tynion IV, on a book called The Department of Truth. Like Harris, Simmonds offered a trove of valuable advice in exchange for new ink.

“We’re pretty much cornering these guys with ‘Hey, you wanna get tattoos?,’ and then that gives us eight hours to pick their brains,” Calvert said. “And it’s pretty funny, because [Simmonds] was like, ‘Oh, I see what you’re doing here, but that’s OK because I love talking about comics.’ At least we’re developing these relationships in a unique way.”

Prather tattooed Simmonds in Austin, Orlando, and Fort Worth. As it happened, Simmonds did the “B” cover for Hiraeth’s first issue. Since then, Prather has also tattooed artist Ben Templesmith (30 Days of Night), and they hope to get him to do an alternate cover for a subsequent issue of Hiraeth.

Networking with established artists is no guarantee of success, but it has been helpful for Calvert and Prather’s goals. Ultimately, they would love to see Hiraeth picked up by a major publishing house, but to get a foot into those doors, every industry veteran they’ve spoken with has told them they need to have three issues ready should the fabled big-time meeting ever grace their calendars, so they’ve set a goal to have three issues done by the end of 2025.

******

With their first book finished, they’re confident they can adhere to that timeline, but they ran into some issues that held up their production. Besides finding ways to hack their creative process, they also had to find a colorist, which proved to be a long process full of disappointment and sifting through a lot of well-meaning amateurs.

“I found a Facebook group called Connecting Comic Writers and Artists,” Calvert said. “I made a post there, said we’re looking for a colorist, just basically created a reference package, and then, literally, we got a thousand people to respond. I spent a week going through a thousand portfolios, and I found about three candidates I liked.”

One of the keepers was a government contractor from Houston named Michael Woods.

“He worked out great,” Calvert said. “His colors mesh very well with [Prather’s] artwork. He adds to the storytelling. He’s been crucial to the process.”

Then there was the issue of lettering, another facet of comic-book production that a creator might think is an easy, DIY part of the process, when it is most certainly the job of a specialist. Enter: Calvert’s brother Scott, also a lifelong comic book fan. Scott works in film and has done a lot of design work for Stanford University.

“I was talking to him one day about our book and some previous letterer candidates that didn’t work out,” Calvert recalled, “and a week later, he called me and said, ‘I watched 40 hours of YouTube videos, and now I know how to letter.’ ”

Courtesy the artists

Scott sussed out a lot of other issues his brother and Prather hadn’t thought of. “We’ve been learning as we go, and he’s very detail-oriented,” Calvert said. “We didn’t know anything about paper, for example. Like I didn’t know that the colors you print with [cyan, magenta, yellow, and black] are different than what’s on a monitor [red, green, blue]. It’s been fun, but all the technical knowledge has made for a learning curve, so it’s taken a while.”

For all those lessons, Calvert and Prather have streamlined their process.

Calvert said, “Now that we’ve gone through the legwork setting it up — I’ve been learning, [Prather’s] been learning, my brother’s been learning — we’re hoping we can do a three- to four-month turnaround on each issue.”

“We’ve discovered a way that [Calvert] and I can get on the same page immediately,” Prather said. “We take an entire day, go to his house, and we sit down and go through each panel and each page, and we act it out, and he tells me what he envisions, I show him how I think it could work, and then we do the thumbnails.”

Calvert said the story, at present, fits 14 issues, though he is trying to “trim it down.” For now, Prather said they are “prepared to have three full issues done, and we’re gonna take six issues and completely thumbnail them, so here’s the whole story, and hopefully take it to some publishers.”

******

Of course, legit networking and a solid creative process don’t matter if the story doesn’t grab anyone. Which begs the question: What is Hiraeth about, anyway?

Pronounced heer-eyeth, the word, defined on the first issue’s title page, refers to a “kind of homesickness. A nostalgia for somewhere you cannot return to, that no longer exists, that never was. A grief for the lost places of your past. Places you may only return to in your imagination.”

If you’ve ever stared at the Roku City screensaver and gotten a little sad that you don’t live there, hiraeth is sort of what you’re feeling.

Following an introduction by an outlandish elfin host with purple hair and blade-style sunglasses, we meet a young boy named Logan, riding in the car with his mom en route to his beloved grandfather’s wake. Whether Logan understands the concept of death or refuses to remains to be seen. Near the end of this scene, he asks his mom about his Pop. “I know you said he’s gone, but if he’s gone, where did he go?”

Courtesy the artists

His mom sounds a little exasperated at his confusion (“Honey, we’ve talked about this,” she says) and hopes for the best, allowing Logan to carry the toy sword he brought but not his Lone Ranger-esque mask, which he stuffs in his pocket. Logan wanders through Pop’s house, now filled to bursting with food and relatives, their ambient small talk drifting across the panels like vapid clouds. His parents argue about the age-appropriateness of a wake, and Logan interacts with his big, bearded, boisterous Uncle Mike, who treats him to a huge piece of cake before remanding him to a room full of cousins. Logan, who doesn’t know any of these kids, still thinks his Pop will make an appearance.

“You’re too old for this,” says his dad, leaving him with a slammed door and cake on the floor.

Logan sits in sadness, puts his mask on, thinks about his grandfather. And then he leaves all his relatives behind and makes his way to his grandfather’s inner sanctum — presumably a garage, where more of Pop’s mementos remain. He pokes around until he is confronted with a large demon clad in coveralls, emerging, apparently, from a cardboard box.

As I got to the end of the issue, I thought about the way Prather depicted Logan’s evening, the montage of people talking, pinching his cheeks, taking out trash, the general sense of disorientation when surrounded by so much “adultness” you feel when you’re a kid and made to attend these sorts of things. Everyone is tall, and many are strangers yet familiar enough to reach down and pinch your cheeks. Woods’ colors subtly highlight Logan’s and his folks’ emotional distress as Calvert’s narration washes over the wake like a sighing breeze. While the fantastical elements are slight, the hints of things to come — at the beginning and the end of the issue — foretell that Logan is in for a wild ride across the five stages of grief.

Prather admits that the first issue is a little light on action, but it is, after all, setting the stage, and it ends on a suitable cliffhanger.

“The second issue has a lot more emotion, a lot more fantasy,” he said. “The first is pacing you to the next 10 issues, where it gets really crazy and adventurous. In the first issue, Logan is just inside a house with his parents. And what got me really excited is that in the second issue, now we get to have a lot more fun adventure stuff.”

As Logan proceeds farther into this fantasy realm, Prather said, he will confront the stages of grief, trying to avoid succumbing to Despair.

“Without giving too much away, our ‘big bad’ in the story is Despair,” Prather said. “When we first meet him, he’s like this doting wise man who wants to help, and then the second time we meet him, he’s going to take off his beard. … I don’t want to spoil it, but I think my character design for Despair is really scary.”

Calvert said a lot of their inspiration came from kids’ movies from the ’80s and ’90s, which he thinks were a lot darker than they are now.

“You go see a Pixar movie today,” Calvert said, “and in most cases, there are, like, no real bad guys or threats, but you look at a movie like All Dogs Go to Heaven … they actually go to hell in that movie, and it’s a children’s movie! We wanted to introduce a story that has gravitas and real danger. I remember being terrified as a kid at the end of Little Nemo because he meets the Nightmare King, but I liked being scared as a kid.”

While they certainly revere the heavy situations in Don Bluth-era children’s entertainment — recall that the happy ending of A Land Before Time still exists in world doomed to extinction — they want to help kids make sense of the scary things in the world.

“We went into this project wanting to create a story that parents could give to their children, that they could read to start conversations about grief,” Calvert said. “When my grandfather died, I watched my nephew go through that, watched my brother have those talks with him about death. We’ve started talking with some psychiatrist friends that my brother knows, and I’m really trying to structure the book in ways that are actually helpful, by using a therapist’s input. Denial is the big thing in Issue 3, and when I finalize that script, I’m going to send it off to these therapist friends to ask if there’s anything else they think would be useful in helping a child understand that part of grief.”

******

Based on the first issue, there’s a lot of promise in Hiraeth — the writing is crisp and naturalistic, and the art is friendly, nuanced, and intentional without getting fussy or distracting. Logan is alternately frustrating for his naivete and sympathetic for just how alone he seems, especially when he pulls the mask out of his pocket and slips it on. The visuals are laden with foreshadowing and metaphor — a lantern, Logan’s mask and sword, the lighthouse painted on the side of a moving truck — all of it portends to a story that is exciting, sad, and affirming, the type of story (like a good Pixar film) that impacts both adults and kids in similar ways. It’s a story that can resonate with everyone, and if it gains an audience as its chapters unfold, it probably will.

For now, though, Calvert and Prather are thrilled that they’ve made it this far. To pay for the book’s printing, they launched a Kickstarter campaign that met its funding goals in only 24 hours. After learning how to tune up their creative process, Issue 2 is coming along nicely. To celebrate, they’re throwing a party on the Near Southside at the Boiled Own Tavern on Saturday with a magician, a DJ, and a signature cocktail created by Scott Calvert called the “Wishcaster.” The party is also sort of a demonstration of the duo’s ability to market themselves.

Courtesy the artists

“Most of the people who make a lot of money with their Kickstarters are because they’ve been published and have garnered an audience,” Calvert said, “and rather than have a publisher taking money, they talk directly to their audience, but we don’t have that reach and audience yet. So, instead of trying to parking lot-pimp this book for 10 years and try to generate an audience, our goal is to create a quality book, show that we can do some marketing for it, and then go to a publisher and say, ‘Look, this is the caliber of work that we’ve done with only our own resources.’ ”

But even if Calvert and Prather’s wildest dreams remain unrealized, they’re bound to see Logan find his way through grief and reach acceptance one way or another. Even if it takes another 15 years. After all, what matters to them is telling a story. To them, telling a story is the thing that matters most.

Courtesy the artists