When Carla Thompson attended a music competitions conference in early 2012, she did so as the board chairperson of a competition that had lost its longtime president two years earlier. Still, she was hopeful for the future of Van Cliburn International Piano Competition and the prospect of new leadership.

During the meetings for competition organizers, Thompson met Jacques Marquis, the director of a performing arts group (Montreal’s Jeunesses Musicales), and found many of the qualities that her organization needed for a new director.

“When I came in as board chair, I was determined to take [my] job out of the executive office,” she said, referring to her dual role as board chairperson and decision-maker for the nonprofit. “The face of the Cliburn needs to be a paid professional CEO. That was my first mission.”

Marquis impressed Thompson in several ways. The charismatic nonprofit director headed finance committees and filled leadership roles within the music competition federation.

“Throughout lunch, I figured out he had a piano degree and a degree in business administration,” Thompson recalled. “We’ve never had those credentials” in a Cliburn director.

She also found the French Canadian to be highly personable and gregarious.

“He was a kick in the pants,” she said with a laugh, referring to Marquis’ penchant then and now for spontaneous jokes and laughter. “I enjoyed that part of him and knew in my mind [we needed someone like him] as we sought younger supporters. He was a breath of fresh air, and there wasn’t anything he was afraid to tackle.”

That summer, Thompson invited Marquis to visit Fort Worth and learn more about The Cliburn.

What resulted from that trip was transformative, both for Marquis and The Cliburn organization, which grew considerably in prestige and reach in the years after. This month marks the 10-year anniversary of the CEO’s hiring, and since he’s so humble, we thought it best to celebrate him through others rather than force him to brag about himself. Thompson recalled many good times during Marquis’ first stay in Fort Worth.

“We laughed about the heat for months,” she remembered. “He said, ‘Well, let’s give it a try.’ That’s how he came on as a consultant. We knew we needed some extra help” heading into the 2013 Van Cliburn International Competition.

The 14th international competition was particularly emotional for the Cliburn team. In early 2013, Van Cliburn died at 78. The man who captured the world’s attention in 1958 when he beat two Soviets to claim the top prize at the first International Tchaikovsky Piano Competition did not directly lead his namesake organization, but his consummate presence at Cliburn piano competitions and advocacy for the contests made him something of a benevolent patriarch for the nonprofit.

“Losing [Cliburn] was a total blow,” Thompson said. “We didn’t know what effect it would have on the organization. There is so much sentimentality and love for him. I think everyone just dug their heels in and did everything in spite of that.”

Managing the complexities of a musical competition that requires housing and transporting dozens of competitors as well as directing concerts at multiple venues and international press coverage is incredibly grueling work, Thompson said, but Marquis stepped into the role seamlessly.

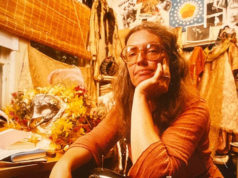

Courtesy The Cliburn

Under his leadership, The Cliburn has expanded its community outreach programs while growing the reach and prominence of its famed international piano competition. When Marquis was hired as president and CEO of The Cliburn in early 2013, the piano competition garnered half a million views that year. The most recent contest that saw 18-year-old Korean Yunchan Lim win gold brought 40 million online views across 177 countries. While streaming has grown as a medium for viewing live performances over that same time period, said Maggie Estes, The Cliburn’s communications director, the nonprofit has invested considerably in technology and streaming platform subscriptions to optimize its online presence.

Cliburn medalist Daniel Hsu said he began watching Cliburn contests as a young kid. The quality of the performers has steadily increased over the years while the event has grown in prestige, he said.

“Since 2017 [when I competed], it is clear that every competition every year gets bigger and bigger,” the bronze medalist said.

While high turnover is not uncommon at local nonprofits, the core team at The Cliburn averages well over a decade of experience each. Estes said Marquis has cultivated a familial work environment, and those bonds continue outside of the workplace.

It’s not just the employees who benefit from that support network. Hsu said Cliburn staff always exceed expectations when managing the careers of past medalists.

“I will say the artist-manager relationship is a special one,” he said. “Coming from the artist’s perspective, you have to feel like your manager and management company believe in you and believe in your story and the message that you are trying to convey. You have to trust that they have your best interest at heart and that they want what is best for you as well. I have been blessed to work with [artistic director] Sandra Doan, [Estes, and Marquis]. They have been so great and have been helping me build the career that I want to have and the career that I want to live.”

The Cliburn’s programming has expanded a lot since Marquis took over. Eight years ago, he launched the Cliburn International Junior Piano Competition and Festival that welcomes 13- to 17-year-old pianists to North Texas every four years. The performing arts organization that was previously known for Bass Performance Hall concerts and piano competitions now presents community concerts throughout the year that feature past competitors. The Cliburn Sessions are another of Marquis’ projects that present genre-bending ensembles in venues like Tulips FTW and The Post at River East.

Marquis told me in 2014 that the Cliburn Sessions were created with both the artist and audience in mind (“ Cliburn, Now in Session,” Oct. 2014). “What I’ve learned the last 20 years is that these artists want to share their love of the music, to do something beyond large concerts, where there is little audience interaction. Today, for instance, conductors regularly speak with audiences, so things have changed.”

Hsu’s Cliburn Sessions debut two years ago at The Post was memorable for several reasons, he said.

“It was so much fun,” he said. “Typically, I would just speak once, maybe right after the intermission or a big work. At The Post, I was able to sort of paint the story from beginning to end. I was able to speak briefly and quickly before every piece and walk [concertgoers] through the journey. For that program, I had a redemption-styled theme. We were coming out of COVID. Everybody was struggling with what we had to face with that pandemic.”

Thompson said her continuing volunteer work with the Cliburn is inspired by her love of helping young musicians as much as by her love for the music.

Marquis is “very involved with the competitors,” she said. “He is also heavily involved with their career management. All through these 10 years, he has found performance opportunities for much more than just the finalists. We tell [the competitors], ‘Don’t leave. Stay. If you stay around, you’ll be asked to fill in for a concert.’ There are more and more opportunities.”

For concert pianists at the beginning of their careers, she added, it is the little things like an unexpected opportunity that matter.