The number of backlogged criminal cases in Tarrant County is staggering by any measurement. Republican district attorney candidate Phil Sorrells recently put the figure at 40,000. This number represents serious crimes, including 266 murder cases, but many of the pending cases are for nonviolent offenses, whether they be trespassing, failure to provide identification, or possessing recreational drugs.

In 2019, District Attorney Sharen Wilson filed 3,750 misdemeanor charges for marijuana possession, making it the county’s most common offense that year, based on reporting by the Dallas Observer. Under Wilson’s administration, Tarrant County has remained one of the only large Texas counties to neither decriminalize possession of small amounts of marijuana nor offer a jail diversion program for recreational pot users.

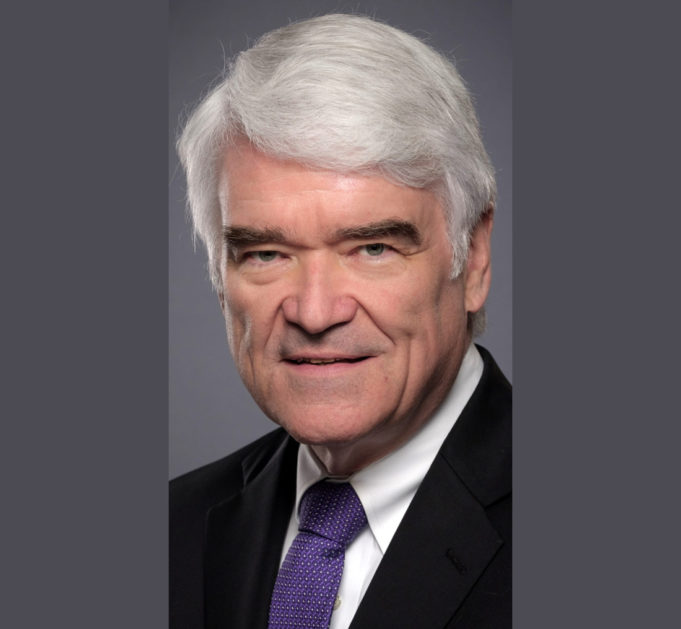

Addressing that backlog has become a central topic of the district attorney’s race that pits Sorrells, a longtime county criminal court judge, against Democrat and former prosecutor Tiffany Burks in November’s midterms. In pitching his plan to reduce the backlog to local legal watchdog Larry O’Neal via a recent Facebook Live interview, Sorrells offered a solution that will only make things worse.

“We have to get visiting judges in here,” Sorrells said. “We have the staff in the DA’s office” to handle those cases.

By visiting judges, Sorrells is referring to retired judges who, based on our reporting, frequently fail to follow Article 16 of the Texas Constitution, which mandates that elected, appointed, and, yes, visiting retired officials take the Oath of Office before working cases. Our magazine has found that visiting retired judges are the only state officials who routinely dodge this constitutional requirement, likely because adhering to Article 16 would pause their cushy retirement checks (“No Authority,” June 22). And with judges, following the money is always a good place to start when investigating judicial malfeasance.

“There are visiting retired judges who are willing to come to get some extra money,” Sorrells said on the show, referring to the roughly $500 a day they would make doing work that elected judges should do but refuse to for some reason — probably afternoon tee times.

On any given day, Tarrant County’s criminal courts downtown in the Tim Curry Criminal Justice Center empty out by around 1 p.m. With court proceedings beginning at 9 a.m., that means a four-hour workday for elected county and district judges who earn between $140,000 and $200,000 a year. For Sorrells to suggest that taxpayers should pony up millions in new funds for active judges to hire their retired golfing buddies to sit in on court trials shows how brazenly corrupt and lazy most Tarrant County judges are.

Here’s a thought: Why don’t Sorrells’ black-robed friends work until 5 p.m. like the average taxpayer or put in the occasional weekend shift to catch up on cases that may be wrecking the lives of thousands of nonviolent defendants? There are people languishing under monthly payments for ankle monitors, supervision fees, and other financial burdens that profit only corporate overlords who fund judges’ reelection campaigns. (We probably answered our own question right there.)

Democrat DA candidate Burks has stated publicly that county prosecutors should undertake a systematic review of backlogged cases to evaluate which ones need to be prioritized and which can be disposed of through dismissal or plea bargain. After every case has been analyzed, and after a short pause of court cases to allow prosecutors the time and resources to evaluate the backlog, the DA’s office will have a more accurate assessment of their workload, and judges and prosecutors can address the remaining cases.

Beyond being constitutionally and often statutorily unqualified, visiting retired judges have a reputation for presiding over unethical or politically motivated cases that active, elected judges do not want to touch for fear of jeopardizing their careers or getting disbarred.

Unlike elected judges, visiting retired judges in North Texas are hand-selected by David Evans. The presiding judge of the Eighth Administrative Region that includes Tarrant County falsely assigned one non-senior judge as a senior judge to more than 100 criminal cases (including a handful of felonies) between 2015 and 2022 (“Who’s Watching the Judges?,” May 12). The false assignments should be retried, but Evans refuses to acknowledge the problem and we have seen no evidence that the defendants even know this judge was assigned under a false title.

Evans’ office also has nothing to say about Judge Jim Hogan. After retiring from Wichita County’s misdemeanor Court at Law No. 1 in 2010, Hogan is listed as a non-senior retired judge on Evans’ public list of retired judges eligible for assignment. A review of 56 recent Order of Assignment forms, all signed by Evans, reveals that over the past two years alone Hogan has been assigned to civil, criminal, and family court cases 23 times as a senior judge, despite the fact that he is publicly listed as non-senior. A spokesperson for Evans’ office has ignored multiple requests for an explanation of the alternating judicial titles that appear to allow Hogan to rule on district-level felony cases outside of Wichita County.

Hand-selecting judges may allow Evans or the DA’s office to pick judicial officers willing to deprive defendants of their constitutional rights when it serves the interests of the powerful. It’s an ugly system and one that Texans are beginning to rise up against. Several parents who have founded nonprofits and lobby legislators regularly have told our reporters that systemic changes are coming to Texas’ courts. Among the proposals are bills that would make it easier to impeach judges and DAs, changes to the State Commission on Judicial Conduct, and the addition of cameras to every courtroom in Texas.

The unethical behavior of many judges here and across Texas may well be condoned by the Supreme Court of Texas. The highest court in the state recently issued a memo saying that visiting retired judges can disregard Chapter 75 of the state government code that governs how visiting retired judges qualify to continue service as a type of judicial officer known as a senior judge.

In the July memo, the Office of Court Administration, the state agency that provides resources and information to the state’s judicial branch, directed judges to “notify the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court that you elect to continue serving as a judicial officer […] prior to your retirement or not later than 90 days after your retirement.”

The directive contradicts the statute on senior judges which clearly states that deciding to become a senior judge can occur only after retirement. More than any elected or appointed official in Texas, judges are held to the highest standards when it comes to fulfilling statutory and constitutional requirements. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled in 1992 that “the judicial acts of a retired judge who has not met the statutory requirements to be an assigned judge at the time he purports to act are absolutely void.”

Any visiting retired judge who fails to complete the steps outlined in Chapter 74 or 75 of state government code could be seen as failing to be statutorily qualified to preside over any case.

The authority of a memo does not supersede a government statute, and the Office of Court Administration may be trying to cover for judges who failed to follow the law.

Indeed, documents we obtained from Texas Chief Justice Nathan Hecht reveal several Tarrant County judges erroneously requested senior judge status while still actively serving in office. In 2010, Judge Vincent Sprinkle, who oversaw misdemeanor cases, formally asked to serve as a senior judge three weeks before he retired, thus failing to fulfill the steps listed in the statute and possibly voiding his authority as a senior judge. Texas laws forbid public officials from holding two governmental positions of profit simultaneously — the type of conflict that faced Sprinkle due to the Supreme Court’s failure to follow the rules set out by Chapter 75. If Sprinkle presided over any case during that period, a defendant could reasonably argue that the judge held two incompatible positions and therefore was not qualified to preside over any case. Documents from the Supreme Court of Texas reveal that neither Sprinkle nor the chief justice at the time acknowledged or took steps to correct the error that possibly undermines Sprinkle’s judicial authority to this day.

Tarrant County judicial records reveal that several county judges who oversee misdemeanor cases notified Evans that they had elected to serve as senior judges by informing the chief justice of their decision, but a spokesperson for the Texas Supreme Court told us that only district and appellate judges are required to notify the chief justice’s office about retirement. The spokesperson’s comment possibly conflicts with an opinion from the 1975 Texas Attorney General which quotes relevant state statutes. No retired judge can preside over cases until that that judge accepts an assignment by the chief justice, the letter reads.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals can and has overturned rulings by visiting retired judges who failed to properly fulfill the requirements listed under Chapter 75 of state government code.

The Supreme Court may be attempting to clean up botched or missing paperwork and erroneous assignments that could undermine past judicial rulings. While retired district-level judges consistently seek senior judge status, not every retired county judge in Tarrant County has, and some of them have presided over felony cases after retirement.

The assignment of former misdemeanor judges to district-level (felony) cases in Tarrant County appears to violate Chapter 75’s mandate that visiting retired judges preside over cases “of the same dignity or lesser as that from which” the judge retired, meaning longtime DWI judges are understandably barred from hearing capital murder cases, for example.

We reached out to a Texas Supreme Court spokesperson for clarity on whether criminal county court judges who wish to continue service as visiting retired judges are required to notify Justice Hecht’s office upon retirement and were told that answering that question would require giving legal advice — the official reason the highest court in the state dodged us.

This story is part of City in Crisis, an ongoing series of reports on unethical behavior and worse by local public leaders, featuring original reporting.

This column reflects the opinions of the editorial board and not the Fort Worth Weekly. To submit a column, please email Editor Anthony Mariani at Anthony@FWWeekly.com. Submissions will be gently edited for factuality, concision, and clarity.

This article should be viewed as the tip of an iceberg poised to sink the SS Good old boys club of Tarrant County… Hopefully she goes down with all hands on deck. Kudos to the Editorial Staff at Fort Worth Weekly for having the balls to initially break this story and the fortitude to keep digging through the epic pile of malfeasance in spite of the brazen corruption exhibited by politicians and power brokers throughout the County. “illegitimi non carborundum” as there are so many more public servants needing the kind of vitamin D only the light of truth can provide.