Kelicia Lyons is no stranger to running for office in Tarrant County’s Precinct 6. Speaking from her home in South Fort Worth, the investigator who collects evidence for the state attorney general described her drive to serve the public.

“This area has grown a lot,” she said, referring to southwest Tarrant County. “We have a lot of Hispanics who have moved here. A lot of our middle school populations are mostly Black and Hispanic. I noticed that we never saw our constable in our community.”

Four years ago, Lyons, an active Black community volunteer, decided that she was going to change that. In 2018, she ran for constable as a Democrat in her home precinct. In Tarrant County, one constable and one justice of the peace (JP) are elected every four years to serve each of eight precincts.

Tarrant County’s eight constables each earn an annual salary of $115,000, according to Tarrant County’s 2020 budget. The licensed peace officers who serve warrants and civil papers are tasked with acting as the bailiff for the JP court in their elected precinct. Tarrant’s eight JPs earn just under $130,000 a year for their role in presiding over cases that may involve misdemeanor crimes, civil disputes, and eviction cases. They also perform marriage ceremonies.

Lyons’ Republican opponent, Jon Siegel, won by 14,000 votes. Two years later, she ran again against Siegel and narrowed that gap to within 4,000 votes or 5% of 105,316 ballots cast.

The path to JP traditionally begins by serving as constable, but Lyons saw an opportunity to snag Precinct 6’s JP seat from Republican incumbent Jason Charbonnet, who first took office in early 2019. Charbonnet ran a slick 2018 campaign against Democrat Deborah Hall, who, according to several local Democrat officials, did nothing beyond filing to run. Charbonnet won by only 3% of 81,876 votes cast.

According to the numerous elected officials and political candidates I spoke to, Charbonnet’s near loss and his fear of losing his seat to a much stronger Democratic opponent, Lyons, prompted him to allegedly pressure white, conservative county commissioners Gary Fickes, J.D. Johnson, and county head Glen Whitley to work in secret with five white Republican JPs to draft a precinct map that stripped tens of thousands of ethnic minorities of their due representation and limited the ability of Tarrant’s three ethnic minority JPs to be reelected in November.

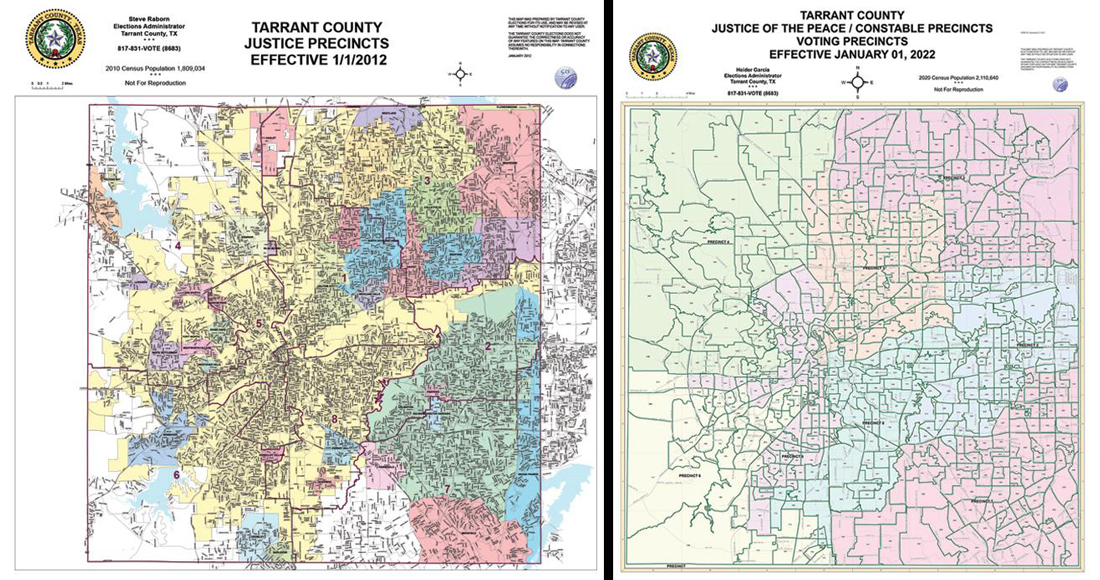

Courtesy of Tarrant County

The new JP map, which was passed at an open meeting on Nov. 9 by Tarrant’s three white Republican commissioners — of the other two commissioners, both ethnic minorities, one abstained and the other voted no — removes political opponents for two white conservative JP incumbents: Charbonnet and Ralph Swearingin. The map, according to the county’s own attorney, dilutes minority representation in one precinct, Precinct 2, which is headed by white Republican JP Mary Tom Cravens Curnutt.

A spokesperson for Charbonnet said he is not commenting on the new JP map. Tarrant’s three Republican commissioners did not respond to my requests for comment.

Sergio De Leon, the Hispanic JP for Precinct 5, alleges that the map was drafted to suppress the rights of a growing base of minority voters, who are unlikely to cast ballots for Republicans. Around 95% of Texas’ 4 million new residents are non-white, according to new U.S. Census figures, and presumably progressive-minded.

As part of an ongoing civil lawsuit to stop the implementation of the JP map, board-certified trial lawyer Steve Maxwell requested a temporary restraining order on the map. Judge Lee Gabriel denied the request on Dec. 8. A county administrator successfully argued that restraining the order would cause problems for March’s primary elections. Maxwell said the decision was disappointing but not entirely unexpected. As he obtains evidence through court-ordered discovery proceedings, he believes that the next judge will rule more favorably.

Within days or weeks at most, Tarrant County will be at the center of a second lawsuit, this one a federal case that aims to overturn the JP map. Through legal arguments at a federal court in the Northern District of Texas in Fort Worth, Maxwell said he will use maps and demographic data to demonstrate that Tarrant’s three Republican commissioners and five Republican JPs diluted local minority representation in violation of the Voting Rights Act, the landmark federal legislation that was drafted to stop and reverse decades of voter suppression in the South.

JP De Leon put it simply. “According to the Voting Rights Act, you cannot crack away precincts and you cannot pack them elsewhere to achieve your objectives.”

The intent of the three commissioners and five JPs, De Leon believes, was to “dilute minority voting strength. It will take a federal lawsuit to shine a light on what they have done and strike down the map that they have passed.”

Against the backdrop of the pending federal lawsuit is a similar filing by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) that alleges that Texas’ Republican leadership misused its redistricting powers to carve a path for state Republicans to remain in power for the next 10 years. Maxwell’s team has reached out to the DOJ to request that the federal investigation include a look at the events leading up to the Nov. 9 commissioners court meeting and the current JP map.

Tarrant County’s demographics tip in favor of new, progressive leadership, Maxwell said, and Republican leaders see gerrymandering or carving up voting districts as their last best hope for clinging to power.

“Republicans are preserving their offices and power by gerrymandering [so] that a minority of the population controls the state,” he said. “It’s just flat wrong. It’s not democracy. That’s what we are fighting.”

*****

With every passing year, Tarrant County grows younger and more diverse. The average age of Tarrant’s 2.1 million residents is 34.9, according to state data. The Lone Star State added more new residents than any state in the nation over the past 10 years, and half of that growth is attributed to Hispanics.

The 2020 Census revealed an 8.6% decrease in white representation across the country over the past decade, while the percentage of Americans who identify as multiracial increased by 276% to 33.8 million. Ethnicity remains a strong indicator of partisanship. According to the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan think tank, only 8% of Blacks vote Republican while 63% of Hispanics and 72% of Asians vote Democrat.

“It is a natural progression,” De Leon said. “The state and county are diversifying. We are now seeing that diversity is not concentrated in one area. The traditional North- and Southside Hispanic population is now growing into the suburbs, and you are seeing more and more local races becoming competitive.”

A narrow majority of Tarrant County voters cast ballots for President Joe Biden, and that swing toward progressive candidates is playing out in county races, he added.

After narrowly winning against a Democrat who spent little to no money on her campaign four years ago, Charbonnet was nervous about this fall’s election against Lyons, De Leon claims.

Earlier last summer, De Leon said he received a phone call from Christopher Gregory, a conservative white JP who represents Precinct 4. De Leon said Gregory wanted to discuss possible JP map redistricting. De Leon told Gregory that any discussion was premature because the official census figures had not been released yet. Because Tarrant’s JPs do not write laws, they are not bound by the U.S. Constitution to redraw districts every 10 years like state legislatures are. Tarrant County’s commissioners court can redraw the JP map at any time, so De Leon felt no urgency to look at precinct redistricting at the time.

Later that summer, De Leon says Gregory contacted him again, this time to tell De Leon that Tarrant County’s commissioners (presumably the three white Republicans) were willing to adopt a new precinct map if five out of the eight JPs in the county agreed to it. De Leon alleges that the phone call was the first indication that Tarrant County’s conservative leadership discussed the map outside of a public meeting, violating Texas’ Open Meetings Act, the state law that requires elected and public officials to discuss matters of public interest during public meetings only, never privately. Again, De Leon stated that he had no interest in pursuing redistricting.

During the Nov. 9 meeting, Gregory told the commissioners that he reached out to De Leon in May and June multiple times to discuss redistricting.

“Fast-forward to the Sunday before the Nov. 9 vote,” De Leon said. “I get a text message from Charbonnet that read, ‘Hey, there is an item on the agenda about JP redistricting.’ He said he’d have a map for me in the morning. Later that morning, a map was produced. Obviously, we couldn’t make heads or tails” of it due to the quality of the image and lack of accompanying data.

De Leon called commissioners Devan Allen and Roy Brooks, the two ethnic minorities, to see if the process of adopting the map could be stopped. Concurrently, De Leon and five other ethnic minority JPs and constables assessed how damaging the maps would be to minority voting power. On Nov. 9, the JP map agenda item occupied most of the meeting. Charbonnet spoke first. He cited population growth and a need for more even workloads as the reasons behind the redistricting.

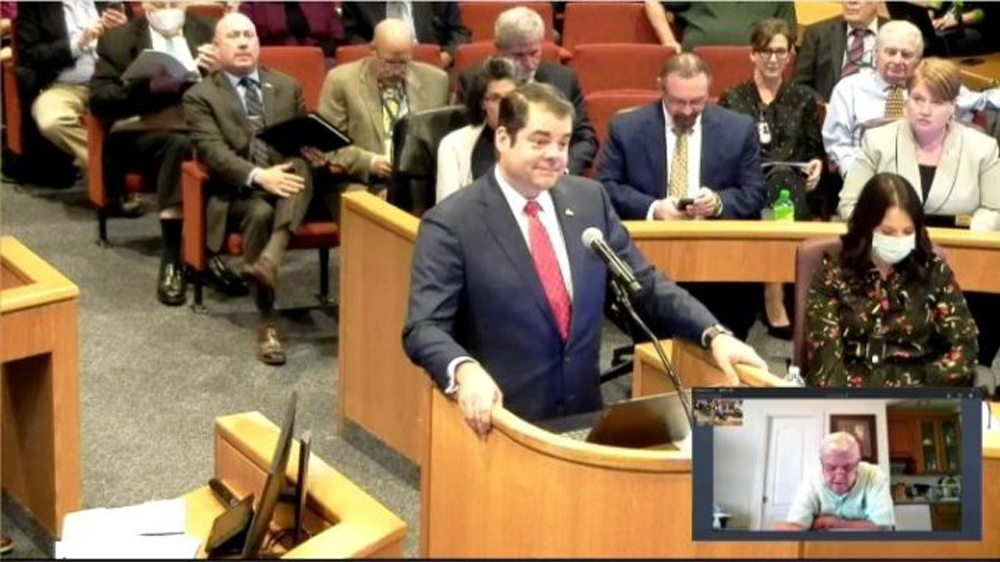

Courtesy of Tarrant County

Charbonnet went on to say the map was drawn by Murphy Nasica, an Austin-based political consulting firm that has worked for Charbonnet in the past, according to documents that I reviewed.

The four remaining Republican JPs then alternately spoke in favor of the new map before De Leon, two other ethnic minority JPs, and a handful of constables spoke against the map and the secretive nature of how the map was drawn.

“I am upset at the lack of integrity in the process,” De Leon said during the meeting. The white Republican JPs who changed the map to favor them “have not talked to any minority JPs [about] who put this map together [and] not one minority constable about what they thought about this map. It is disrespectful to us as leaders, especially the thousands that we represent. What I feel like is that communities of color have been disrespected.”

Charbonnet returned to the podium to defend himself against accusations that he knowingly drew opponent Lyons out of Precinct 6. Charbonnet told the commissioners that there was no way he would know where Lyons lived.

“He knows exactly where his opponent lives,” De Leon alleged to me. “This was done by design. This issue of workloads is bogus. It’s a red herring. This was done to preserve their own incumbencies and political power. This has nothing to do with workloads whatsoever.”

De Leon shared one group text and email that Charbonnet sent to the three ethnic minority JPs the day before the commissioners meeting. In both messages, Charbonnet says the map preserves the incumbencies of JPs from both parties.

“There is no funny business like gerrymandering and taking people out of precincts,” Charbonnet wrote in one text. “It’s to protect the incumbent.”

In an email addressed to the same three ethnic minority JPs, Charbonnet again echoed his understanding that the map he made would take incumbency into account.

“This map takes into account two things, incumbency and workload,” he wrote in the email.

Protecting incumbencies through redistricting is precisely the aim of gerrymandering, but such acts do not constitute crimes under state or federal law.

Lyons, who was present at the meeting, recalled being shocked that the five white Republican JPs and three white Republican commissioners would so brazenly adopt a map during a public meeting when every other speaker vehemently opposed it.

Lyons believes county head Whitley’s questions during the meeting referenced previous conversations among Charbonnet and other Republican JPs in possible violation of Texas’ open meetings act.

Photo by Edward Brown

“I couldn’t believe all the lies that were told by the current Republicans JPs and that the meeting was being recorded,” she said. “After all the damaging information that was revealed, the Republican commissioners and Whitley voted to approve the map. The only thing that mattered was protecting the Republican incumbency seats.”

During the Nov. 9 meeting, Commissioner Allen asked an attorney for the county to describe the legality of the proposed map.

Precinct 2 “is the one that has the most voting rights impact,” the lawyer told the commissioners court. “It was a district that was politically competitive. [The new map] has had a significant impact on the racial balance. It looks as if it may not be nearly as competitive in the future.”

When asked by a commissioner if the new maps appear to be an attempt at retrogression, the legal standard that opens gerrymandered maps to federal lawsuits, the county attorney said “yes.”

In Texas, candidates seeking the nomination of the Democratic or Republican party can file for office beginning Nov. 13, meaning that Lyons would have been able to formally file to run by the following Saturday. Charbonnet’s window for drawing her out of Precinct 6 was closing.

“The commissioners couldn’t table the agenda item if they were going to save Charbonnet’s seat,” Lyons alleges.

One second after the last speaker closed his remarks, Commissioner Fickes motioned for a vote, which was seconded by Johnson and then Whitley. Maxwell said that the vote may not have been legitimate for a number of reasons. Beyond potential violations of Texas’ open meetings act beforehand, questions remain over whether there was a quorum when the map was adopted. Johnson attended the meeting remotely, and Allen and Brooks physically left the room as the vote took place.

At the meeting, one member of the district attorney’s office spoke plainly.

“Judge, we have lost a physical quorum,” Chris Taylor said.

No, we did not, Whitley responded.

“I would respectfully request that we take maybe a five-minute break to make sure that was a valid vote,” Taylor said.

After the break, the final vote was tallied 3-1 with Brooks voting against the item and Allen abstaining.

“Glen Whitley is a so-called numbers guy,” De Leon told me later. “For him to adopt a map with no numbers is egregious.”

Lyons said the whole ordeal was orchestrated by Charbonnet. She alleges that a fellow JP confided in her that, in June, Charbonnet told the JP to get “Kelicia Lyons off my ass.”

Lyons said that several confidential Republican sources told her that Charbonnet contacted several prominent local Republicans and asked them to pressure county head Whitley into going along with the plan. Even if she had not been drawn out of her precinct, Lyons said that Precinct 6 is no longer competitive for ethnic minority candidates under the new map. She opened her laptop and showed me a long spreadsheet that broke down the districts within each precinct by voting history.

“There were 141,000 registered voters in Precinct 6 in 2020,” she said. The Republican JPs “have taken out 60,000 voters. They left 80,000. 52,000 are Republicans, and 28,000 are Democrats.”

*****

Soon after the 1870 passage of the 15th Amendment that guaranteed the right to vote to formerly enslaved citizens of the United States, Southern states began a systematic effort to disenfranchise Black voters through arbitrary tests, taxes, and outright violence.

“One was the literacy tests,” said Max Krochmal, author and associate professor of history at TCU. “You had to demonstrate your ability to read and write and to understand clauses in the Constitution. Then there was a grandfather clause that said if your grandfather had not been able to vote, then you could not vote.”

In the decades following the passage of the 15th Amendment, courts in the South upheld state-sanctioned voter suppression efforts. In Texas, taxes were levied on anyone who wished to vote in the primaries. The taxes had to be paid at the beginning of the year, which was a time of year when poor sharecroppers had the least cash on hand.

“African Americans, Mexican-Americans, and even poor whites were removed from the voting rolls in Texas as a result,” Krochmal said.

By the 1930s and 1940s, Southern states built an interlocking set of legal restrictions — backed by lynchings and terror — that worked to systematically deny Black men and women the right to vote.

“In 1965, even after the sit-ins, the March on Washington, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, African Americans couldn’t elect the people who represented them in much of the South,” Krochmal said. “Finally, the movement kept organizing and compelled the federal government to weigh in with the Voting Rights Act.”

One century before, Union soldiers occupied former Confederate states to ensure that enslaved Americans were freed from forced labor camps that whites then and now euphemistically call “plantations.” Following the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, the federal government once again sent agents, this time registrars, to ensure that Black and brown citizens were allowed to exercise their constitutional right to vote.

The Voting Rights Act, Krochmal said, remains as important today as it was in 1965 because systematic efforts to disenfranchise Black and brown voters continue to this day.

Following Biden’s landslide victory, Republican leaders at all levels of government began tacitly or directly supporting baseless claims by the former president that rampant voter fraud plagued the 2020 presidential election.

To this day, two-thirds of Republican voters believe that the election was rigged, and only one-third of Republicans said they will trust the results of 2024 if their candidate doesn’t win, according to an NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll.

Under the guise of “voter integrity,” Texas’ Republican leadership recently drafted and passed Senate Bill 1. The bill limits early voting and access to drop boxes, two methods preferred by Black and other ethnic minority voters in the 2020 presidential election. Voters in Harris County are losing the ability to cast ballots from their cars — a decision that aims to disenfranchise minority voters in the state’s most populous county. The new law gives poll watchers increased autonomy — a move seen by many as pandering to hysteria over voting fraud on the part of many white Texans. The bill also criminalizes any effort by state election officials to proactively distribute applications for mail-in ballots.

Charlie Bonner, communications director for MOVE Texas, a pro-voting rights nonprofit, told us last year that Texas’ efforts to restrict mail-in ballots should be seen for what they are.

“We have to understand that limiting access to the ballot is an intentional measure to prevent voting,” he said. “That is something that has been built up through voter-suppression laws. We see little to no evidence of voter fraud or any of the associated arguments that partisan conspiracy theorists whip up. When they make those arguments, real people do get hurt when real voters lose rights. We have to push back on that.”

Fighting against Texas’ SB1 and similar voter suppression laws, Democrat leadership at the federal level has been desperately trying to pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act and the Freedom to Vote Act, which are designed to restore parts of the Voting Rights Act that were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013. The acts will also add new protections for minority groups that continue to be targeted by Republican-drafted voter suppression laws.

Fort Worth Mayor Mattie Parker, a Republican, recently chose not to sign a letter by the United States Conference of Mayors that urges the U.S. Senate to pass both pieces of legislation.

“Simply put, I don’t sign onto every letter put out by the organizations of which I’m a member,” Parker recently told the Star-Telegram.

On Monday, Councilmember Chris Nettles sent a letter to U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer that calls on the Senate to pass both pieces of federal legislation that Parker declined to publicly support.

“The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was the final nail in Jim Crow’s coffin,” Nettles wrote, “but in 2013, this law was gutted, and nine states (including Texas) were given the freedom to enact discriminatory voting laws yet again. Since then, these Southern states have been allowed to pass unregulated laws — laws like closing Houston’s 24-hour voting locations and reducing Tarrant County’s polling locations by 36%. Laws that target urban cities are laws that target Black people.”

Extreme partisanship is on the rise, said former JP Manuel Valdez. The longtime JP for Precinct 5 who stepped down a decade ago after serving that office for nearly 35 years said that his biggest concern for Tarrant County politics, and the nation as a whole, is the inability of politicians to look past their political affiliations when serving the people of Fort Worth and Tarrant County.

For most of his career, “everybody seemed to get along with everyone,” Valdez said. “We had our political differences. As far as the elected officials went, we could communicate with one another almost any time.”

Valdez said he has maintained close friends on either side of the political aisle. He laments the current political climate that sees compromise as weakness and working with political opponents as acts of betrayal.

“Sides are being drawn,” he said. “We saw it in the last election, and we are seeing it today. Nowadays, there is such hard language being used. I don’t feel comfortable with that kind of situation.”

Throughout most of his career, whenever a constituent needed help, Valdez said he could pick up the phone and call any elected official in Tarrant County.

“I always got a call straight back,” he said. “Toward the end of my tenure, if I made a phone call, I wouldn’t hear back from Republicans. It seemed to be that the climate of the politics was changing to where we only speak to our side and not their side. A lot of that stuff flows from the top. It gradually finds its way down to counties like Tarrant County.”