In October, Chef Jon Bonnell celebrated 20 years as head honcho of Bonnell’s Fine Texas Cuisine (4259 Bryant Irvin Rd., 817-738-5489) by throwing a party with bespoke wines and as much shrimp-and-cheese grits, brisket, and dainty single-bite Key lime pies as his friends, family, and admirers could eat. Twenty years ago, the former middle school math and science teacher had recently gotten married, celebrated his 31st birthday, and was a mere three years post-culinary school.

“We hit the market at a time when there was room for us,” Bonnell said. “We did a lot of things right and a lot of things wrong.”

In addition to the other opening day jitters and the sluggish post-9/11 economy, the predictably unpredictable Texas weather threw the grand opening for a loop with a power outage.

One of the reasons Bonnell’s proved so popular was the location: outside of downtown on the west side of the Fort, with easy access to those traveling westbound from Arlington and eastbound from Parker County.

“I went to great lengths to detail a business plan, and nothing worked out the way I thought,” Bonnell said with a laugh. “There were times we did really well, but in the second year, we were in trouble. For the first year, everyone was going to the new place. Then we had about two years of lackluster sales.”

The Bonnell empire, officially Bonnell’s Restaurant Group, now includes four restaurants. In addition to the fine dining establishment, Buffalo Bros Pizza, Wings & Subs (3015 S. University Dr., 817-386-9601) opened in 2008, the seafood restaurant Bonnell’s Waters (301 Main St., 817-984-1110) opened in 2013, and a second Buffalo Bros opened downtown (415 Throckmorton St., 817- 887-9533) in 2019. A fifth casual burgers-and-beers concept is set to open soon.

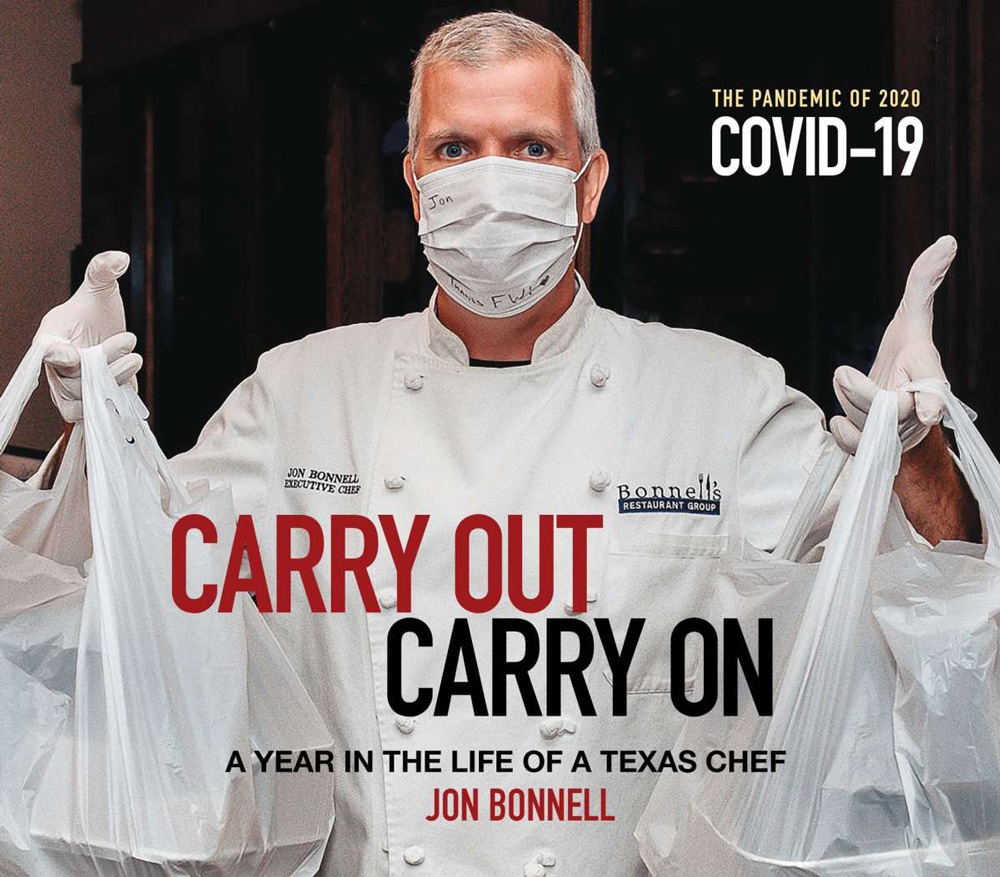

Courtesy Amazon.com

Here at the Weekly, we have episodically chronicled those restaurants with staying power in our Eats section. Despite the seemingly endless revolving doors in Sundance Square, West 7th/Crockett Row, and Waterside, some of our town’s best stories have happened in the restaurants that are nearing the century mark or have come close to a half-century. Someone in our stable of Eats writers routinely covers Bonnell every couple of years, mainly because he produces a book or a new restaurant about that often, but Bonnell’s Fine Texas Cuisine is a mere sweet summer child when compared to other local landmark eateries. While we might not spotlight those as often as we ought to, a restaurant that withstands the attention-span-of-a-gnat foodie blogosphere for two, three, or more decades should also be celebrated.

The Original Mexican Eats Café (4713 Camp Bowie Blvd., 817-738-6226) and Carshon’s Delicatessen (3133 Cleburne Rd., 817-923-1907) began slinging their unique kinds of home-cooking (Mexican and Jewish, respectively) in the (original) roaring ’20s, and Joe T. Garcia’s Mexican Restaurant (2201 N. Commerce St., 817-626-4356) had seating capacity for only 16 in the 1930s.

Legend has it that calf fries, a.k.a. Rocky Mountain oysters, were invented at the original Riscky’s Steakhouse –– the doors of the restaurant at 120 Exchange Ave. (817-624-4800) also opened in the ’30s.

Barbecue moved away from the Stockyards when Angelo George opened his eponymously named eatery (2533 White Settlement Rd., 817-332-0357) in 1958. In 1968, Mama’s Pizza (multiple locations) opened near Texas Wesleyan University, and there are still locations in Fort Worth, Arlington, and Mansfield if you like New York-style pizza and eschew the well-done crust and gloopy center of trendier Neapolitan-style pizzerias. Drew’s Place (5701 Curzon Ave., 817-735-4408) has been serving some of the best down-home comfort food you’ll ever find for 34 years, and Michael’s Cuisine (3413 W. 7th St., 817-877-3413) was dishing out experimental Southwestern fare before Bonnell even began his second career as a chef. I have fond memories of the quirky chipotle meatballs on an early-in-a-relationship date, although I no longer remember who that particular suitor was.

Photo by Laurie James

Before Dayne’s Craft BBQ (2735 5th St., 682-472-181), Goldee’s BBQ (4645 Dick Price Rd., Kennedale, 817-480-4131), Hurtado Barbecue (205 E. Front St., Arlington, 682-323-4151), Panther City BBQ (201 E. Hattie St., 682-499-5618), and Smok-a-Holics (1417 Evans Ave., 817-386-5658) cracked Texas Monthly’s 2021 Top 50 barbecue Joints in Texas, there was Railhead Smokehouse (2900 Montgomery St., 817-738-9808), celebrating 35 years in 2021. Their smoked half-chicken and barbecue sauce are the best here or anywhere –– and I will fight you on that. Although special props are due to Goldee’s young-gun owner-operators Jalen Heard, Nupohn Inthanousay, Lane Milne, Dylan Taylor, and Johnny White –– hitting it as the Monthly’s best barbecue restaurant in Texas the first year out is epic, and doing so in spite of a pandemic is the stuff of legend.

It’s worth a moment to consider that two of the Fort’s longest-tenured food establishments, Roy Pope Grocery & Market (2300 Merrick St., 817-732-2863) and Paris Coffee Shop (704 W. Magnolia Ave., 817-335-2041), would have permanently closed this year if not for Lou Lambert and his team. Lambert, who grew up on his father’s Fort Worth stories, says he had no real desire to own a grocery store until he realized Roy Pope was like the neighborhood bodegas he’d grown to love during his time in New York and San Francisco.

“Dad used to have a meal at Paris Café every Saturday with a group of his TCU buddies,” Lambert said.

Despite what he calls “a giant learning curve,” he’s gently modernizing the two landmarks. Roy Pope took 13 months to reopen, and Paris just closed for a massive facelift, hopefully to open back up early next spring. Lambert said he’s already been told by a group of Fort Worth old-timers that he better not screw this up. With respect to those folks with opinions — Fort Worth foodies are brutal when it comes to the tried-and-true joints our parents and grandparents loved — Lambert and company’s massive breath of fresh air is absolutely needed if those eateries are to survive in this decade.

Also of note, Spiral Diner (1314 W. Magnolia Ave., 817-332-8834) turns 20 next year. Cowtown’s first solely vegan restaurant was founded by Amy McNutt, who gambled that those Fort Worth diners wanted to try vegan hot dogs, Frito pies, nachos, and mac ’n’ cheese at least once. Nonna Tata (1400 W. Magnolia Ave., 817-332-0250) celebrates 15 years of bringing a little bit of Italy to Fort Worth this year. Owner Donatella Trotti crashed the long-time boys’ club of restaurateurs by tapping into the city’s hunger for Italian food that didn’t come with unlimited soup, salad, or breadsticks, and Executive Chef Molly McCook has won consistent acclaim for Ellerbe Fine Foods (1501 W. Magnolia Ave., 817-926-3663) over the last 12 years. Her elegant, beautiful resto sits just up the block from Nonna Tata, and McCook has been praised by the Weekly, foodie mogul Rachael Ray, Texas Monthly, and the prestigious James Beard Foundation, among others. McCook was a 2020 Beard Foundation semifinalist.

I could go on, but the Weekly’s electronic archives go back to only about 2004, and my memory gets spotty before then. I am also restraining from a Chow, Baby-style rant about why good restaurants go out of business (but it’s an absolute shanda that Fred’s Texas Café, which predates Bonnell’s and everything in and around Crockett Row, has to leave the flagship location in December). The surviving non-chain restaurants from 2010 or thereabouts that made it through the last decade include Cat City Grill (1208 W. Magnolia Ave., 817-916-5333), Magnolia Motor Lounge (3005 Morton St., 817-332-3344), Salsa Limon (multiple locations), and a duo of Felipe Armenta-concepted restaurants, The Tavern (2755 S. Hulen St., 817-923-6200) and Pacific Table (1600 S. University Dr., 871-887-9995). The sublime Mi Dia from Scratch (1295 S. Main St., Grapevine, 817-421-4747) also celebrated 10 years in early October. Chef Gabriel Deleon has a background similar to Bonnell’s –– culinary school, then traveling while working for other chefs, then opening a restaurant that serves food he’s passionate about. In DeLeon’s case, the food is the cuisine traditional to Mexico City, with a stop in Santa Fe.

Even though the restaurants in my meander through Eatin’ Pants Lane are memorable, none are fine dining establishments. For the Fort Worth restaurant scene to compete with our neighbors to the east, the town requires higher-end non-chain restaurants to keep conventioneer and anniversary celebration dollars right here in the 817. We need the kinds of white-tablecloth service and menu that Bonnell’s provides.

*****

When I moved back to Tarrant County in 2004, there were only a handful of fancy dining choices. Saint-Emilion (3617 W 7th St, 817-737-2781) was a perpetual anniversary celebration restaurant and, for a long time, the field of one winner for the Weekly’s Best of French food. The restaurant’s location in what would become known as our Cultural District made it one of the city’s best kept dining secrets. Del Frisco’s Double Eagle Steakhouse (812 Main St., 817-877-3999) held up one end of Fort Worth’s barely redeveloping downtown by the Convention Center, and Reata Restaurant (310 Houston St., 817-336-1009) was ensconced in the old Caravan of Dreams on the other end. Reata started up in the old Bank One Tower in 1996, so 2021 is the silver anniversary for restaurant president Mike Micallef and company. Reata survived a tornado, a location change, and the departure of half a dozen chefs (many of whom went on to find acclaim on their own). One of the reasons for the success of the upscale cowboy cuisine restaurant is location, Micallef said.

“When you were in downtown Fort Worth [in the early aughts], there were just private clubs where people could have a nice dinner,” he said. “There weren’t restaurants where people could just walk in.”

Good luck just walking into Reata at this point without a reservation, especially on TCU home game weekends. (Micallef is a TCU grad.) Even a freak Texas tornado couldn’t stop them.

“The 2000 tornado closed us for 42 days,” Micallef said. “We reopened, then left in January 2001.”

Courtesy Instagram

Between the closure caused by one of the worst weather events Fort Worth has ever seen and the move to what is now the edge of Sundance Square, Micallef and crew refined the Reata catering department, which would become a critical factor in Reata’s surviving the 2020 pandemic.

Although COVID restaurant closures in 2020 essentially halted fine dining in town, it wasn’t the first time Fort Worth had a contracture to the high-end dining scene. During the economic crash in 2009, things paused for those who have specialty businesses –– and two-margarita lunches became a thing of the past, according to Micallef.

“In 2009, group lunches and lunches for people traveling for business decelerated, but the special events kept up,” he said.

A key difference in the then-and-now realities of running a fine dining restaurant was that 12 years ago, the supply chain wasn’t an issue.

“With COVID came restrictions in both facilities and the supply chain,” Micallef said. “Cattle didn’t disappear, but the ability to process them did.”

Michael Thompson’s eponymously named restaurant survived that tornado, the same economic contracture, and the wretched West 7th Street construction when Montgomery Street closed as well. “As scary and as terrible as the COVID lockdown was, we’ve been through worse,” Thompson said.

Bonnell’s, like Reata and Michael’s, survived the 2020 shuttering of in-restaurant dining due in part to the chef’s/owners’ respective willingness to swivel out of the models that served them so well.

“The city didn’t need fine dining in a crisis,” Bonnell said.

Nobody in the industry knew how long sit-down dining would starve after the restaurants closed due to COVID in March. Bonnell’s shut down on a Wednesday and opened back up the following Saturday with six staff, including Bonnell and wife Melinda Bonnell. The campaign literally came from the chef’s Facebook page –– every morning, Bonnell posted a “Hello, Quarantinis” message listing the daily menu. It was a pre-packed take-it-or-leave-it meal for four, which came refrigerated with heating instructions and was delivered literally on the side of the road.

“It was an absolute mess the first day,” Bonnell said. “We served 400 people and the line of cars stretched back to Hulen Street on the access road from Bryant Irvin Road, two hours long.”

Courtesy Instagram

Meals included King Ranch casserole, shrimp and grits, brisket, chicken-fried steak, fried chicken, and pasta dishes. At first the food was whatever was in the refrigerator.

“Eggs, fish, and steaks,” Bonnell said. “Anything that was going to go bad.”

Bonnell and other high-end restaurateurs had been used to the luxury of planning meals around what foods were seasonally available and what his local suppliers could provide. The break in the supply line proved challenging.

“Food, ingredients, and recipes dominate my thoughts, but that didn’t make a difference in the pandemic,” he said. “We needed to feed the highest amount of people for the lowest price point.”

In addition to the supply chain, menus were limited to the size of the refrigerators in the restaurants’ kitchens. Thompson said that at Michael’s, the hardest thing about the supply squeeze was rotating the inventory. Instead of a set menu, Thompson offered a pared-down bill of fare, rotating between a few favorite dishes. And every week, he said, people would be disappointed because they invariably wanted what was available the week before.

One thing that proved fruitful was the ability to continue to sell alcohol.

“The alcohol-to-go lifeline from the governor really helped,” Bonnell said.

For Reata’s pandemic pivot, Reata on the Road brought set-menu meals for four to outlying locations, including Aledo, Benbrook, and various Fort Worth neighborhoods.

“Our catering crew had the idea about hot spots –– pre-selling family meals for four and then delivering them,” Micallef said.

Reata on the Road charged $49 for the meals and gave $10 back to local charities like school athletic programs, which were also financially strapped because of the pandemic. Reata on the Road made the Wall Street Journal last December, when the paper wrote about how fine dining restaurants had pivoted.

*****

Bonnell and Micallef are not alone two decades in –– there are several other chef/owners in town who’ve turned one restaurant into an inland empire. Tim Love, a chef at Reata when the tornado closed the kitchens, took some of the uptown cowboy cuisine ideology and opened Lonesome Dove Bistro (2406 N. Main St., 817-740-8810), arguably the first fine dining place in the Stockyards, in 2000. Love now owns 14 restaurants from here to Houston and Tennessee. He’s had only one spectacular failure –– Lonesome Dove’s New York outpost flopped within a year, and opinion runs 50/50 whether we in Fort Worth care about what they think in Manhattan. Love Style Inc. has learned a few lessons, and apparently some of those are from Reata: Former Reata chefs Brian Olenjack and Andrew Dilda are both now working for Love. Love Tim or hate him, it’s hard to argue with 14 successful restaurants, all of varying price points.

Felipe Armenta, who’s a lot less of a press guy than either Bonnell or Love, has also quietly, successfully operated half a dozen restaurants with his partners, including the previously mentioned Tavern and Pacific Table. Maria’s Mexican Kitchen (1712 S. University Dr., 817-916-0550) is named for his mama, and there’s Press Café (4801 Edwards Ranch Rd., 817-570-6002) and the newest in Armenta’s family, Towne Grill (9365 Rain Lily Tr., 817-916-0390). His only misstep was the demise of the wonderful Cork & Pig Tavern, a victim of the ill mojo of that corner of Crockett Row.

Armente’s big COVID pivot was into ViraTech, a sanitation company that developed a relatively nontoxic way to rid restaurant surfaces of viruses, bacteria, and fungi.

So if he doesn’t own the oldest or the most restaurants, and if he doesn’t sell mayonnaise in magazines, why is Bonnell so significant? Perhaps it’s his substantial contribution to local charities –– he chairs or chefs for a number of food-related and non-food-related fundraisers every year. Perhaps it’s the fact that his food is consistently good –– and no recipe is a secret. If you like what you ate, email him, and he’ll send you the recipe. Maybe it’s his civic-minded devotion to his hometown –– the man relentlessly promotes other restaurants on his social media, and while that makes him a hero, it also has made him a target.

Courtesy www.waterstexas.com

Embedded in COVID during the summer of 2020, George Floyd, who was Black, was killed by a white police officer, and the world tilted a little. Downtown Fort Worth, like many cities, became a hot spot for marchers who were protesting inequality in policing, with ample reason. As of this writing, the former Fort Worth police officer who fatally shot Atatiana Jefferson in her family home has not gone to trial, although a date has been set for January 2022. Some of that marching cut right through downtown and right into the time when restaurants were reopened at 50% capacity. There were bullhorns, and the mostly white patrons got nervous.

“The protesters came onto the patio [at Waters], which they had every right to do,” Bonnell said. “I got called out to the front as a community leader to get [the protesters’] message to the mayor.”

Bonnell didn’t hide in the kitchen or lean on the police department presence already in downtown. Video shows a visibly emotional Bonnell on the restaurant’s street front, speaking to and embracing one of the protest leaders. The next night, Bonnell had cold water and signs supporting the protesters. In 20 years, Bonnell has never truly faltered. He’s not chasing women (unless they’re passing him in one of the triathlons in which he participates), and he didn’t allegedly buy a fancy sports car in the middle of the pandemic with money that should have gone to beleaguered staff. So raise a glass to Jon Bonnell –– and as long as we’re toasting, to Brandon Hurtado, Lou Lambert, Molly McCook, Michael Thompson, Donatella Trotti, the young men from Goldee’s, and anyone else brave or foolish enough to open a restaurant, fine dining or otherwise. We’ll see what the class of 2021 looks like 20 years in.