When you’re not a North Texas native, you hear the name “Gentling” with a hard initial “g” bandied around the art scene without it meaning very much. Most of the major exhibitions of Scott Gentling (1942-2011) and Stuart Gentling (1942-2006) took place decades ago. I knew the fraternal twin brothers as the artists behind their mammoth Of Birds and Texas series, stemming from a self-published book in 1986. Now, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art offers the retrospective Imagined Realism that shows the brothers to be far more than that. Where other artists pick a specialty and stick to it, I’m fascinated by artists like these who advance in all directions at once.

The Gentlings were born in Minnesota, and their family moved to Fort Worth when they were 5. Their parents’ marriage was stormy, which made the brothers greatly dependent on each other. Scott and Stuart lived together for their entire lives, except for their college years, when Scott received a classical art education at Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) while Stuart majored in history and English at Tulane University. After school, they re-settled in their parents’ home, where Scott was the more introverted one focused entirely on art while Stuart worked on maintaining their social connections, often an important part of an artist’s career. While the exhibit holds a letter in which Scott counseled Stuart to develop his own artistic style, the two brothers are generally considered as a single creative unit. They employed various media, but most of their works are on paper with the method known as drybrush watercolor, where the artist dips the brush in water and squeezes it out before dipping it into pigment.

Let’s dispense with the least interesting part of the show first. Among their Texas landscapes, Scott’s “Cathedral” from 2002 shows then-President George W. Bush in a canyon near his ranch in Crawford. We can’t tell that the man in the picture is the president, since his back is to the viewer and he’s dwarfed by the canyon walls. This is certainly a more interesting use of Bush than the brothers’ soft-focus 2002 portrait of him in the show, which they began while he was still governor of Texas running for the presidency. Then, too, there’s Scott’s 2007 painting “Sovereign,” depicting a fallow field full of upturned dirt, which holds interest if you know that it was executed shortly after Stuart’s sudden death from a heart attack the year before. Their landscapes are attractive enough, but we’ve seen comparable work from other artists depicting the Lone Star State’s open spaces and big skies.

The show goes relatively easy on the Gentlings’ bird paintings, though Scott’s painting of a wild turkey is astonishing when you reflect that he was 16 when he painted it. The brothers’ emulation of John James Audubon is clear in the early works, as they imitated the 19th-century painter’s plain white backgrounds and flat compositions, aiming to capture the scientific detail of the birds the way Audubon did. However, there’s enough here to show the artists evolving over time. The 1997 painting of a snowy owl against a black background has a vividness not seen in the earlier paintings. You feel like it might turn its head to look at you. Besides birds, the Gentlings also painted insects, organizing them on the paper like specimens pinned to a collection board.

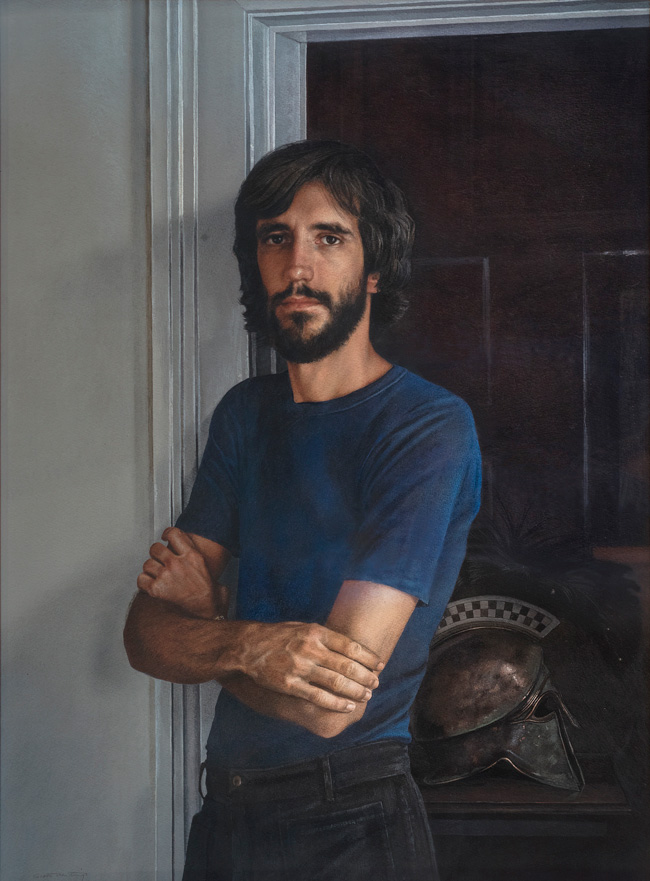

Courtesy T. Brent Rowan Hyder, Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Many of the portraits here (like the one of Bush) were commissioned by wealthy and notable individuals and accepted so the Gentlings could earn their living. Sometimes individual elements pop out, like the electric blue blouse in the 1985 portrait of Kit Moncrief, the philanthropist and wife of the oilman Charlie Moncrief. A deeper achievement is the 1976 portrait of Brent Hyder, which captures the serenity of the long-haired, bearded young man with his arms casually crossed. (The doorway behind him and the room beyond containing a helmet were added 10 years later.)

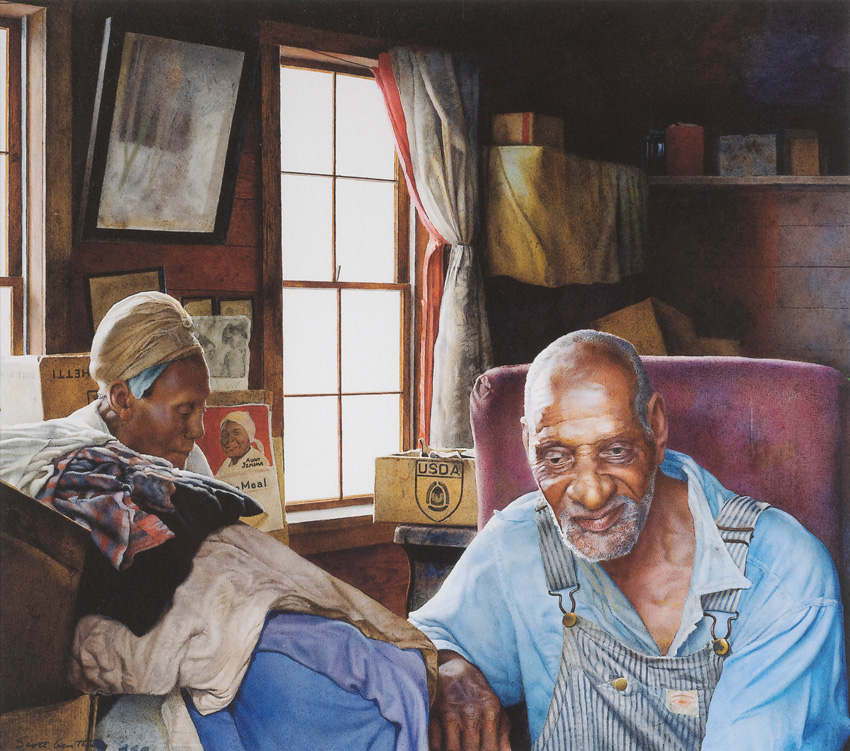

Courtesy Amon Carter Museum of American Art, purchase with funds provided by Edward P. Bass

However, not all the portraits here were done for money. The twins’ early paintings like “Rain Crows” and “Eddy” are pictures of Eddy and Clemmie McGary, poor sharecroppers from East Texas, that were done with the same attention to physical detail and character. The show also has student works such as Scott’s 1965 self-portrait, an abortive foray into oil painting, as well as a colored pencil portrait of William Faulkner, an author whom the brothers had been obsessed with as teens. Portraits are also visible among Scott’s etchings, a medium that similarly absorbed his attention during a rather undistinguished career at PAFA. The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth loaned its neighbor the Gentlings’ portrait of Jane Goodall, done when the famed primatologist visited North Texas in 1990. The brothers begged her to sit for the unorthodox painting, where she’s placed off center on the left side of the composition and facing away from the viewer. After she had departed, the artists filled in the right side with a chimpanzee skull placed on a table, a touch that delighted Goodall when she saw the finished work.

The exhibit also boasts some imposing pencil portraits of fellow artists who shared the Gentlings’ hobbies. Andrew Wyeth, like the Gentlings, collected historical outfits, and the museum’s own collection yields dressed in a tri-corner hat and a long waistcoat, where the pencil even captures the delicate lacework around the coat buttons. Some of these garments are on display as well, clothes made fragile by time and showing how small and thin their wearers were. A painting of red coats from French and British military units makes for an intriguing study of color. Ed Ruscha, another painter with a national profile who befriended the brothers, contributes a foreword to the book of the exhibit and also appears as the subject of a pencil portrait, wearing an ornate green velvet coat and a bicorne hat like Napoleon’s.

Courtesy Amon Carter Museum of American Art

The other big pencil portrait is one of Ludwig van Beethoven, which Scott claimed came from a dream in which the great composer sat for him. The sketch captures the man’s stormy personality and pockmarked skin, and it’s a better picture of the man than the Gentlings’ 1960 painting of him in the museum’s collection, which is not in the exhibit. If you don’t know about the Gentlings’ work for Bass Hall, you might not guess that they were avid fans of classical music who learned to play instruments later in life. The show contains a selection of their miniature portraits of Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Copland, and others, which they made for their own amusement.

More impressive are the large-scale still-life paintings of stringed instruments. Without oil paint, it’s hard to capture the particular sheen given off by the varnished wood of violins and cellos, but the Gentlings’ watercolors render it quite well. The Bass family selected the Gentlings to paint the trompe l’œil domed ceiling of Bass Hall depicting the open sky. The exhibit contains a study for that ceiling. If only we could see some of the brothers’ mural designs for the concert hall’s walls, which went unused. (What can I say? In a big civic architectural project, work done by contracted artisans will always go by the boards.)

Courtesy Anne and Barney Holland, Amon Carter Museum of American Art

The most revelatory part of the show relates to the Gentlings’ work with Aztec culture, which was fired when Stuart saw the collection of Aztec art and artifacts at Tulane. (Even before that, the Gentlings were enthralled by Henry King’s 1947 film Captain from Castile, which was presented in color and shot on location in Michoacán, both unusual for Hollywood movies of that time.) Stuart became absorbed enough in the ancient culture to learn their language, Nahuatl. The Gentlings made several trips to Mexico to conduct research at the site and painted “Eagle and Cactus,” a striking portrait of a golden eagle holding a rattlesnake in its talon, much like the one in the center of Mexico’s flag. They intended their work to become a project as massive as Of Birds and Texas, but it never came to fruition during their lifetimes. While most self-described Western artists focus on tribes that are native to their own area (and have surviving members who can be interviewed), the Gentlings’ imaginations were kindled by the splendor of the great empire to the south.

In particular, they wanted to evoke the Aztec cities, which so dazzled the Spanish conquistadors that they thought they were hallucinating. The people they regarded as savages had built sprawling, clean metropolises of gleaming white stone buildings trimmed with cochineal red, a pigment made of crushed insects that produced a color more vivid than any red dye in Europe at the time. That’s not the only red that shows up in the Gentlings’ paintings and models, as they depict the pyramids to the Aztec gods as stained with the blood of human sacrifices. The vistas of “The Great Sacred Square of Tenochtitlán” and “Distant View of Tlatelolco” (with its irrigation canals cutting across the city) are eye-catching, and they’re accompanied by models built by Scott as studies for the paintings. Still, don’t overlook the interiors of temples that the Gentlings depicted using their knowledge and acquisition of Aztec artifacts. Where their information was lacking, the artists substituted their own imagination. Inevitably, subsequent research proved some of their assumptions wrong while others held up. Even so, these paintings’ vibrant colors help depict the magnificence of this culture before it was destroyed by the Spaniards.

All this goes to prove that the Gentlings were multifarious creatures. While some of their works could fairly be called “realist,” they rejected that label for themselves, and if they were Texas artists, their subjects ranged well beyond the state’s borders or even the American Southwest. Ignoring the modernist and postmodernist trends that washed over the larger art world in their time, Scott and Stuart Gentling followed their own creative star, and Imagined Realism gives us an overview of where it took them during a long and prolific career.

Imagined Realism: Scott and Stuart Gentling

Thru Jan 9 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd, FW. Free. 817-738-1933.

so sorry that the Bird Cafe across from the Bass Hall closed recently. The Gentling brothers bird paintings throughout the building were a wonderful feature

I forgot to add that this was a great article. Fort Worth’s great museums don’t get enough high quality in depth publicity. Thanks Kristian