I hate to say it, but my first major museum exhibit since the pandemic turned out to be a bit of a logistical bummer. Queen Nefertari’s Egypt has been laid out in the Kimbell’s Piano Pavilion to allow visitors to practice social distancing. This means that you may very well have to wait at the exhibit’s entrance in the pavilion’s lobby before you go in. It also means that you have to follow a rigidly marked path through the show, possibly having to wait while the people in front of you are done looking at whatever item of interest they’re viewing before you can move on. I miss the freedom of movement that I enjoyed at museum shows in the time before. Despite all of that, the Kimbell’s latest blockbuster still has plenty to enthrall Egyptologists and the like.

Photo courtesy Kimbell Art Museum.

It is both grimly appropriate and perversely funny that when you first enter the exhibit, you are flanked by statues of Sekhmet, the goddess of the plague. (She was also a healing goddess as well as a protector of soldiers. While ancient Egyptians prayed for her protection, they also believed that she caused plagues whenever they angered her.) The stone figures have the bodies of people and the heads of lionesses wearing cobra-shaped headdresses. It’s striking how daintily the features of the lioness faces are rendered in these imposing sculptures. A similar delicacy prevails in the statuette of the goddess Bastet, a finely chiseled bronze figure of a cat with a disturbingly modern stylization to it.

Photo courtesy of Kimbell Art Museum.

A section of the show is given over to ordinary items gathered from Deir el-Medina, the village that housed the royal family’s support staff, ranging from learned scribes to the guys who started digging the Pharaoh’s tomb as soon as he was crowned. These items

Photo courtesy of Kimbell Art Museum.

tend not to be much to look at (apart from a box with floral motifs used for keeping sundries), but they have a mystical sheen from having survived the millennia. Even a hairpin can inspire awe. This section also includes a number of vessels for brewing beer, and it’s a shame that the museum didn’t have a sidebar on the brew that the ancient Egyptians drank, which was quite different from our beer in its use of ancient grains instead of modern barley, lack of hops, and being considered a food item suitable for children to drink. Our local craft beer devotees would have slurped that up.

Photo courtesy of Kimbell Art Museum.

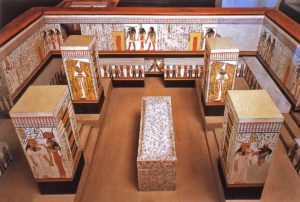

The centerpiece of the show is the gallery containing all the surviving items from Queen Nefertari’s tomb, which was looted shortly after her death around 1255 B.C. Among these items are her mummified knees and a pair of sandals that appear to have been hers. I’m fascinated to learn that she was around 5’6” — tall for a woman of this time — and her shoe size would measure 9. No less impressive is the scale model made shortly after her tomb was uncovered by the Italian Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaparelli, whose findings formed the basis of the Museo Egizio in Turin, whence the show’s artifacts have come to us. This and the three-minute National Geographic video shown at the end of the exhibit let us know what an amazing experience it must be to journey inside her burial chamber. This is particularly important at a time when all travel abroad is inadvisable and travel to Egypt even more so.

Photo courtesy of Kimbell Art Museum.

A great deal of this show is devoted to death, which is because the Egyptians believed that the soul went on living in the next world and thus made provisions for it. Many of the exhibit’s items are funeral objects that the soul would use, including some faience shabti figurines that come in a startling shade of electric blue. Painfully conscious of their finite time on Earth, the Egyptians made things that were designed to last forever. More than 3,000 years later, their objects speak to us.