Behind Dickies Arena, and largely hidden from passersby, several lines of cars crept toward dozens of volunteers who were stocking trunks with frozen turkeys, orange juice, and other foodstuffs as part of a mobile pantry by the Tarrant Area Food Bank (TAFB).

“Most of these folks, around 40%, are brand-new to our services,” said Julie Butner, president and CEO of the TAFB. “These are folks who held two or three jobs and lost one. These are working families, but they don’t have enough money to meet their food needs.”

Butner said the need for massive food pantry operations won’t go away until the economy returns to normal. Fort Worth’s economic recovery has been steady but uneven. Just under 11 million Americans remain unemployed, according to December jobs figures released by the U.S. Department of Labor, and certain sectors of the economy (dining, tourism, entertainment) are still struggling to recover amid a largely uncontrolled pandemic. While rows of shuttered buildings outwardly mark economic upheaval in cities like Detroit and Toledo, Fort Worth’s businesses inwardly carry burdensome debt that will restrict their ability to hire or expand for many years to come.

As of Saturday, 1,361 Tarrant County residents have died from COVID-19. Many more have lost their lives due to delayed medical treatments and other fallout from the pandemic. Texas remains under a mask mandate as the first COVID-19 vaccines begin a slow ramp-up to inoculate an American population that is increasingly open to taking the vaccinations. Just over 70% of respondents to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll said they would “definitely or probably” take the vaccine.

The pandemic struck Fort Worth unevenly, opening generations-old fissures along lines of economic inequality and race. The stories of survival told in the Weekly offer insight into the day-to-day struggles of people in underserved communities who suffered from underdevelopment before the novel coronavirus further decimated them. Community leaders from the East, West, and North sides told us that outright starvation was prevented through close collaborations among nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and government agencies. Charities like the TAFB, with the help of many others, stepped up to feed thousands of families as monetary donations dwindled.

Photo courtesy of Community Enrichment Center

As Fort Worth enters 2021, its residents remain split, both ideologically and politically. For the first time since 1964, Tarrant County voted blue in a presidential election. President-elect Joe Biden earned a narrow 49.31% of county votes and 58% of Fort Worth votes. For now, political winds in Texas and across the nation favor progressive ideals that seek ecological and civil justice. As with millennials, members of the youngest voting contingent — Generation Z — see diversity in all of its human forms as a good thing, according to polls by the Pew Research Center. Less than a quarter of those 18- to 23-year-olds approved of Donald Trump’s presidency, according to the Pew center.

The Nov. 3 election left Tarrant County with a status quo conservative 3-2 majority in the commissioners court, while Republican Sheriff Bill Waybourn defeated Democrat Vance Keyes in a heated contest that pitted reform-minded groups against “rule-of-law” notions of law enforcement.

Whether Fort Worth continues down an economically segregated path or makes room for a larger bloc of Fort Worthians to shape the future, locals may see 2020 decades from now as a formative year on par with the decision of the Swift and Armour meatpacking plants to set up shop on the North Side or the establishment of the military base Camp Bowie in 1917.

*****

Dressed in purply pink, Mayor Betsy Price opened her State of the City speech with optimism and folksy charm. Fort Worth is a city on the ascendency, buoyed by a growing population and an influx of new businesses, she said in February. Local corporations were praised as the mayor made her case for Fort Worth’s business-friendly future. Not one mention was made of COVID-19 — a disease that had yet to raise alarm bells in Tarrant County or anywhere in Texas despite the fact that Trump was notified of the first case in January.

As Fort Worth families set off on spring break vacations, the first massive surges of the disease began hitting North America and popular vacation destinations in Europe and Mexico. Many North Texas families were left stranded overseas or they returned after narrowly escaping a cascade of government shutdowns and travel restrictions. By mid-March, the full extent of the pandemic began to be known. On March 23, Price urged Fort Worthians to shelter in place as Dallas went a step beyond and closed restaurants and bars. Tarrant County experienced its first confirmed COVID-19-related death that month when Pat James died in an Arlington hospital.

Price, joined by Arlington Mayor Jeff Williams and Tarrant County Judge Glen Whitley, announced strict shelter-in-place orders the next day. The declaration, enforceable through fines and possibly jail time, required Tarrant County residents to remain home unless they were performing essential activities.

The term “essential worker,” which had existed in principle, gained tangible meaning as nurses, maintenance crews, delivery drivers, and retail workers were recognized as the men and women who enable modern life. TCU economics professor John Harvey, in an early April interview with us, commented on the irony that many of Fort Worth’s essential workers subsist on low wages.

Those workers “are living on very little, and they are the people who we desperately need to work right now,” he said, referring to the men and women who stock shelves, ship freight, repair roads, and more. “Their industries turn out to be the essential ones. There’s a book called Are Economists as Important as Garbage Men? If all the economists stopped working, it would be a long time before anyone noticed. If the garbageman stopped working, we would notice pretty quickly. [The author] begs the question: Which jobs are really essential and how much of our wages are driven by our subjective values rather than how important someone really is to our day-to-today lives?”

Massive layoffs across the city impacted workers in retail, restaurants, bars, and entertainment early on in the pandemic. Chris Strayer, vice president of the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce, said his team began calling its 1,700 business members to listen to their needs around that time.

“That gave us insight into the programming that companies needed to address their challenges,” he said.

Chamber directors connected displaced workers with new job openings in e-commerce and grocery stores, Strayer said. A top concern for business owners was how to access financial aid like the federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). Chamber staff developed webinars and online resources to guide business owners through the complicated application process.

Fort Worth’s newspapers and magazines were hit by a precipitous drop in ad revenue. The forced temporary closing of restaurants and bars and subsequent slog of an economic recovery have left the Weekly a leaner yet still efficient independent voice in a market that continues to favor pro-business, pro-status quo publications and media.

As Americans adjusted to working from home, swaths of Fort Worth were left without the option of remote work. As reported in Vice, just 16.2% of Latinx workers have been able to work from home, compared to 30% of whites and 37% of Asian Americans. The “telework disparity” was one of several factors that led to disproportionate economic devastation in underserved communities. The inability of Black and Latinx workers to socially distance would play a role in the higher percentages of those populations dying from COVID-19 and contracting it.

By mid-April, large food pantry lines were a daily reality in parts of the North Side. Longtime Northside resident Esmeralda Morales said her family was able to scrape by.

“Some people are going to every church that offers food pantries,” she said at the time. Those churches are “offering essential items. We don’t hear a lot of people asking for [help publicly]. It might be due to a sense of pride. We do see packed drive-thru lines at [the local church]. It’s unreal how many people need help right now. We see a lot of those vehicles go back to our area.”

Morales said Northside residents regularly checked in with neighbors, and anonymous gift card donations went to the poorest and most vulnerable families. Community organizer Arnoldo Hurtado was stranded in Spain at the time but kept his neighborhood informed and connected via a Northside Facebook group page.

“If we stay inside, we starve because there is no food, due to lack of money,” he said. “We’ve learned that it has to be we the people who stop relying on the big, messy political and institutional departments who are only looking out for themselves and their” money.

Willie Rankin, executive director of the Westside-based nonprofit LVTRise, said his community stepped up to meet the challenges of widespread job losses. Residents were checking in on neighbors, especially the elderly, and Westside families were sharing what scarce resources they had, Rankin said this summer.

Eastside resident and Fort Worth school district trustee Quinton Phillips spent the early part of the pandemic guiding the district through an abrupt shift to online learning.

“Schools mean a lot [to the East Side] from a childcare and nutritional perspective,” Phillips said. “That began to affect everything. Parents had to make tough decisions on whether to let young people stay at home rather than miss work.”

Once online classes were available across the district, Phillips turned his attention to his Stop Six community. Working through a nonprofit he cofounded, CommUnity Frontline, Phillips and other leaders organized online mental health forums, made grocery runs for elderly residents, volunteered at food pantries, and raised funds to help struggling families.

“I look at our community as indestructible in many ways because we already had to deal with poverty,” he said. “We can rise through anything, but that does not mean that there won’t be consequences or a loss of life. How long will we last? As long as it takes. The church community and volunteers are stepping up. We can last, but that doesn’t mean that we need to be neglected in the meantime.”

*****

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the Near Southside’s service sector and creative class especially hard. The neighborhood’s economy is fueled in no small part by artists, musicians, and waiters who subsist on gigs. Many singer-songwriters wait tables by day to add financial stability to the fluctuating work by night. When times are good, artists can make a modest but comfortable living, and Fort Worth enjoys the fruits of their creative endeavors. Several new restaurants like Tinie’s Mexican Cuisine and The Bearded Lady were forced to lay off or furlough staff just as they were building followings.

Photo courtesy of BossGirlBites

The nonprofit responsible for developing and promoting that community, Near Southside Inc., created Southside C.A.R.E.S. (Culinary Arts Retail Entertainment and Service Fund) to give $250 grants to struggling workers in the service and entertainment sectors. International R&B sensation and famous Fort Worthian Leon Bridges offered a performance opportunity to Marty and Marilyn Englander, co-owners of Kent & Co. Wines, a bar/restaurant on West Magnolia Avenue, with the idea of organizing a benefit concert for the fund. Near Southside Inc. leaders hoped to raise $20,000 through the April 30 livestream event at Kent & Co. Wines. Soon after singer-songwriter Abraham Alexander opened the two-act virtual concert, the fund tallied $15,000. By the end of Bridges’ set, $63,000 had been raised. Megan Henderson, Near Southside Inc. director of events and communications, said over $150,000 has been raised to date, and more than 500 grants have been issued to help Southsiders in need.

“It was a special night,” Alexander recalled. “All the money we raised was incredible, truly incredible. I’m humbled and thankful. To use our talents that God has given us for something like this, that is humbling. That is what it is all about.”

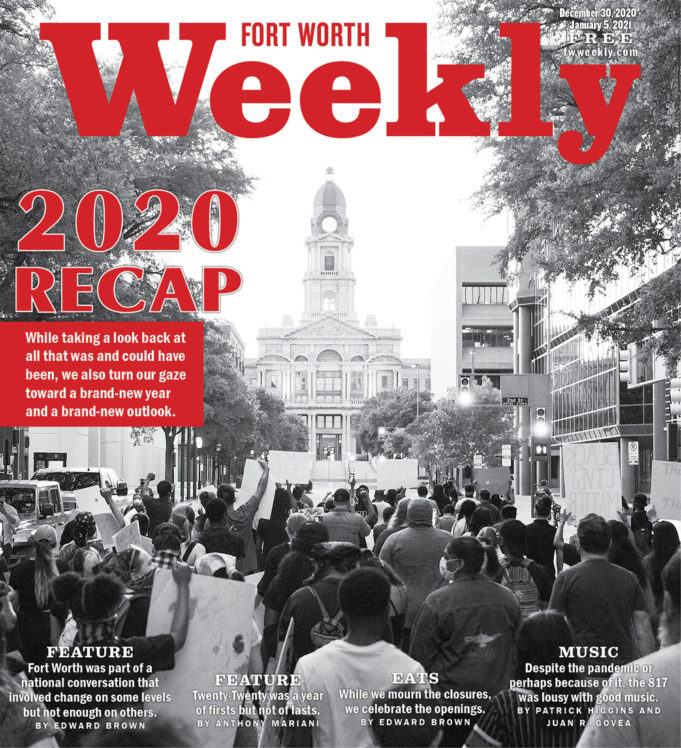

Three weeks later, George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, left a Minneapolis convenience store before being approached by four police officers. A store clerk had called 911 and told police that Floyd had bought cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill. During the subsequent arrest, one officer pressed his knee on Floyd’s neck as three officers looked on. Floyd died on the scene. The officer responsible for Floyd’s death faces second-degree murder charges while the three officers who did not intervene to save Floyd’s life face second-degree charges for aiding and abetting murder. Massive protests over Floyd’s death began in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul metroplex before spreading to cities across the United States and the world.

On May 31, the third day of protests in Fort Worth were marked by the use of tear gas and smoke bombs by heavily armed Fort Worth police officers. Around 50 protesters were arrested that Sunday evening near the West 7th Street Bridge. Police department press releases stated that protesters had thrown water bottles at officers and made verbal threats to damage West 7th properties.

The next evening saw another standoff between protesters and police, this time in front of the Tarrant County Courthouse. In response to the heated confrontations the day before, Price issued a 72-hour 8 p.m. curfew. As a church bell marked the beginning of the curfew, a few hundred protesters approached a line of officers. Police Chief Ed Kraus took a knee and prayed with protesters. What appeared at the time to be a moment of reconciliation would mark the beginning of heavy protests that kept the city on edge as other major cities like Chicago, New York City, and Seattle dealt with violent protests.

For the first two weeks of June, Fort Worth’s protests were driven by several disparate factions — Enough Is Enough, FW4Change, United My Justice, and others — that largely worked together toward the common goals of reducing police violence against unarmed persons of color, reallocating city funds toward public services, and chipping away at a criminal justice system that subsists on incarcerating nonviolent drug users and individuals who suffer from mental health conditions.

Photo by Jason Brimmer

As the Black Lives Matter movement made criminal justice reform a central mandate of its cause, the Weekly dug into local policing and prosecutorial habits that disproportionately harass, arrest, and incarcerate Fort Worth’s poor. Greg Westfall, a criminal defense lawyer with 25 years of experience, said many of the impoverished men and women who languish (and increasingly die) in Tarrant County Jail are where they are due to over-policing.

Speaking in July, Westfall said, “There are a lot of folks who are in the system who shouldn’t be. The defendants are often overcharged, over-arrested, and overlooked.”

Westfall allocates part of his law practice to indigent defense, which pays $50 to $125 per hour in Tarrant County — a small fraction of what a skilled lawyer can earn in private practice. Monetary bail is incredibly efficient at ensuring that the poor remain in jail, he said, where they are less likely to be able to mount a defense. Bail, the mechanism for leaving jail, can be posted in full by the defendant (cash bail) or paid through a line of credit issued from a bail bondsman (bail bond). Tarrant County Jail became a frequent target of large marches where muffled chants of “You are not alone!” were heard by jailed men and women who lacked the financial resources to buy their freedom.

In response to public cries for police reforms and participating in budget negotiations at the city level, local leaders met several protester demands. Fort Worthians sent nearly 300 letters to City Hall, demanding a participatory budgeting process. In response to the letters, every city councilmember except Dennis Shingleton (District 7) and Cary Moon (District 6) held town hall meetings in August. Constituents asked budget-related questions or suggested how city funds should be used.

The final city budget — $1.9 billion — includes increased funds for community-based police programs (partnerships with nonprofits), funds for an expanded Mental Health Crisis Intervention Team, and the removal of police militarization funding from the Crime Control and Prevention District (CCPD), a half-cent tax that raises more than $80 million a year for the police department. A budget was also set for a new 10-member Community Service Professional Program that will respond to non-emergency calls such as “helping stranded motorists, animal-related issues, and calls where no suspect is on the scene,” according to the city.

A spokesperson for the city’s budget office said steps were taken to address requests for greater community-based programming within the police budget.

“Having said that,” the spokesperson continued, “the budget is a process that must be completed in a timely manner. We would encourage citizens to be involved year-round. The CCPD board holds quarterly meetings.”

Newly reelected Sheriff Waybourn has committed to creating a mental health diversion center for Tarrant County.

Speaking to the Weekly in July, Waybourn said the center would “allow us to take people who would benefit from mental health care out of our jail and place them in an environment that would help get them the care they need,” he said.

“Secondly,” he continued, “I hope to bring to fruition a complete reentry program that starts within the jail and partners with private companies and nonprofits to set the table for success as individuals come out of the jail and into the free world. Thirdly, [I will] work to create a use-of-force laboratory that allows our officers and deputies to train on de-escalation strategies and real-life scenarios, allowing our Sheriff’s Office team to keep calm in tense situations.”

*****

In the spring, public schools and universities across the country abruptly closed their campuses to slow the spread of COVID-19. Fort Worth school district leadership was faced with a shortage of tablets and other devices that were needed for the shift to online learning. The district eventually distributed 6,000 AT&T WiFi hotspots so students in underserved communities could access the internet.

A majority of public school students rely on free or reduced meals, meaning the campus closing risked cutting off one of the few sources of healthy food for tens of thousands of children and teens.

The school district, with the help of its food service vendor, SODEXO Magic, began offering meals to-go at select campuses soon after the temporary closing of school buildings. The school district partnered with the TAFB to address food shortages for the families of students. Mobile pantry sites provided 5-pound boxes of nonperishable food to families on select days, a district spokesperson said.

As spring led to summer break, many parents assumed the pandemic would subside enough to allow for a safe transition to in-person learning in the fall. By July, deaths from COVID-19 in Texas reached 4,000. Despite the lack of meaningful progress containing the pandemic, Trump tweeted that “SCHOOLS MUST OPEN IN THE FALL!!!” Texas public school leaders followed several shifts in reopening mandates throughout July, both from Gov. Greg Abbott and the Texas Education Agency (TEA), which governs public and charter schools in the Lone Star State. School district leaders initially went into the month with the understanding that campuses must reopen due to TEA guidelines that tie funding to classroom attendance.

Abbott loosened those restrictions in mid-July by allowing local public health officials to order schools to delay opening campuses for health-related reasons. In late July, officials from Tarrant County Public Health (TCPH) ordered a delay in school classroom reopenings until Sept. 28 while allowing for online learning six weeks before that date. The order did not affect religious private schools.

“Discussion with community partners, including school superintendents, elected leaders, as well as medical professionals, were considered when making this decision,” read a statement by TCPH.

Wealthy white families rallied outside of the Tarrant County Administration Building on July 27 to demand that public and private schools reopen immediately.

“It is frustrating and confusing that one doctor has in her hands the fate” of every family in Tarrant county, one mother said, speaking to county head Whitley inside the building as around two dozen parents listened on.

The “one doctor” was Dr. Catherine Colquitt, an infectious disease specialist with decades of professional experience. The following day, indicted Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton again reversed the state’s position on school reopenings and allowed school district trustees to decide when to open campuses. On July 30, Fort Worth school district trustees voted 8-1 to begin online classes on Sept. 8. After four weeks of online learning, the board planned to reopen campuses if public health considerations allowed. A small but vocal contingent of white parents, largely from the affluent Tanglewood neighborhood, began contacting trustees and speaking at board meetings, demanding that classrooms reopen immediately.

The debate over when to reopen campuses basically fell into two camps. Many parents, public health officials, and teachers worried that reopening classes too quickly would endanger teachers, lead to repeated school shutdowns, and spread infections to vulnerable populations as children returned to multi-generation families living under one roof. With less access to health care and paid time off, many families from Black and Latinx communities urged caution. A small but vocal contingent of white parents conversely believed that the emotional stress and potential academic setbacks posed by virtual learning posed a bigger danger than COVID-19, which has claimed 335,000 American lives since January and counting.

After numerous heated school board meetings, Fort Worth trustees adopted a plan to allow all campuses to reopen by Oct. 19. That compromise may not have been good enough for parents at Fort Worth’s wealthiest public schools: Overton Park Elementary and Tanglewood Elementary. Both schools used a TEA loophole that allowed a school campus to reopen if access to WiFi was inadequate. The use of a loophole by uber-rich white parents that was intended to protect underserved communities (and other actions taken by the small group of elites) smacked of white privilege in action, said TCU associate professor of history Max Krochmal in September.

Fort Worth school district’s “default decision-making processes have long prioritized the needs of wealthy white families (a tiny percentage of the district) over the voices of the massive Black and Brown super-majority,” he wrote, “and the current moment promises to exacerbate this trend. Like the larger phenomenon of whiteness, this pattern is often invisible, and it often creeps up without warning. It extends far beyond the board to inform the decisions of executive staff members starting with the superintendent on down to middle managers and even teachers on campuses.”

*****

Texas remains one of the most restrictive states to vote in, but several grassroots groups successfully chipped away at voter suppression in 2020. In September, lawyers with the Texas Civil Rights Project (TCRP), a 30-year-old equality and justice nonprofit, eliminated an arbitrary means of invalidating ballots: signature analysis. For decades, county election officials and volunteers were allowed to discard ballots simply based on the perceived difference between two signatures by the same voter.

“We filed suit to make sure that voters were provided Constitutional due process for any signature mismatch issue,” said Hani Mirza, TCRP senior attorney.

The nonprofit’s second successful litigation effort gives Texans the ability to register to vote online when residents apply for or renew their driver’s licenses. Mirza said nearly 2 million Texans update their driving information through the Department of Public Safety’s online portal. The biggest prize for reform-minded groups, universal mail-in ballots, remains verboten in the Lone Star State.

“We have to understand that limiting access to the ballot is an intentional measure to prevent voting,” said Charlie Bonner, communications director for MOVE Texas, a nonpartisan group that works to promote voting and civic engagement among young Texans. “That is something that has been built up through voter-suppression laws.”

Texas typically ranks near the bottom in voter turnout, but the 2020 election brought out record levels of early voting in Tarrant County with 729,558 local residents casting their ballots before Election Day. Early voting across the state (which accounted for 9.7 million Texans or 57% of registered voters) broke 2016 totals, according to the Texas Tribune. President-elect Biden won 49.31% of Tarrant County votes while Trump won 49.09%, marking the first time since 1964 that Tarrant County voted blue in a presidential election.

Just days before the Nov. 3 election, Sen. Kamala Harris visited Fort Worth to make her case for ousting Trump and for turning the country away from xenophobic presidential tweets and policies and for returning the presidency to an office that defers to reason, justice, and empathy when making decisions that affect the lives of more than 300 million people.

“Let’s get rid of mandatory minimum” sentences, she said at a socially distanced outdoor rally near First St. John Cathedral on the South Side. “Let us decriminalize marijuana and expunge the record of people who have been convicted for marijuana offenses. Let’s shut down the private prisons. Let’s get rid of monetary bail. People are sitting in jail for weeks and months and years because they can’t afford to get out, which makes it an economic justice issue as much as a criminal justice issue.”

In the final presidential electoral tally, Biden (with 302 electoral votes) trumped the president, who garnered 232 votes. Two Tarrant County commissioner incumbents (Democrat Roy Brooks and Republican Gary Fickes) won reelection, thereby maintaining the five-member court’s status quo of four male commissioners (three of whom are white) and no Latinx representation in a county that is 27% Hispanic.

Fort Worth’s city council will expand from nine to 11 members in 2023. Two new districts will be created to accommodate that growth. The expansion was approved by locals in 2016 as part of an amendment to the city charter.

Arguably the most lasting change brought by 2020 is renewed civic engagement from all political persuasions. The swell of young progressives who took to the streets for weeks of protest against social and economic injustice — the same millennials and members of Gen Z who were struck hardest by the recent recession — have made their intentions known along with swells of Trump supporters who will make their political allegiances known in the post-Trump era. The 2021 state legislative session and Fort Worth Municipal General Election (May 1) will be the first test of whether grassroots social justice causes that gained boisterous support in street protests across Texas can translate into new city leadership and meaningful state reforms.