The new exhibit at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth is a silent storm that transcends The Now. Robyn O’Neil: WE, THE MASSES surges with violent impotency. The artist embraces the inherent superficiality, even frivolousness of art and transforms drawing into a kind of ritual, making it something that appears to have always existed for its own sake. Her calibrated sincerity laced with un-ironic patience transports the viewer to a harrowing dreamstate just beyond the sturm und drang of daily life at this, the end of the world. O’Neil invites us to eternal slumber, and we are thankful for the opportunity.

Born in Nebraska, raised mostly in Texas, and educated in Texas and Chicago, the relatively new Californian experienced her big break of sorts in 2004, when she was chosen to exhibit in the Whitney Biennial. Her resume also includes a lucrative Hunting Prize. WE, THE MASSES is the first survey of the fortysomething artist’s work. Drawing from 2000 until now, the exhibit was organized by associate curator Alison Hearst and features dozens of pieces. Since most of O’Neil’s work is massive in scale, her drawings of nightmarish, frozen-tundra tableaux populated by thousands of tiny middle-aged white men in black track suits and dead trees or raging oceans look handsome among the Modern’s boxy galleries. “I hope viewers get a sense for how much I love what I do,” O’Neil told Hearst. “I hope they see, in every single square millimeter of all these drawings, that I deeply care. … What I care about more than anything is that these drawings are perceived, even if only subconsciously, as visual specimens of empathy.”

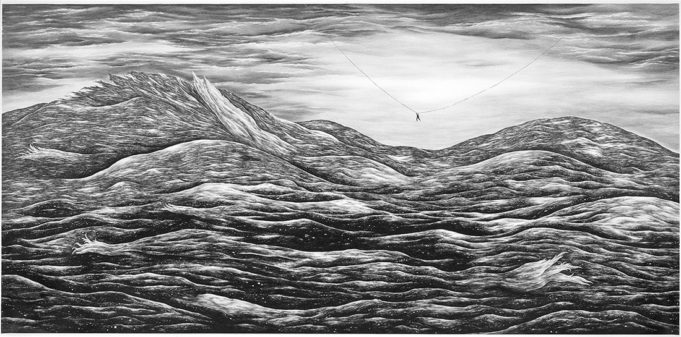

The trouble with thematic art is that when seen in a collection it can tend to seem repetitive. That’s not to say there isn’t a lot to unpack here, starting with O’Neil’s sweat equity. To draw just one swell of her sea waves must take a full eight hours with her weapon of choice, a no-nonsense .5mm mechanical pencil. (The Modern gift shop is selling working replicas of the ones the artist uses.) As some artists are formalistically restless, with varying results, O’Neil is devoted to her rich though perhaps under-appreciated medium. Her insistence on rhythm, her love of narrative, her desire to do what she loves makes her a Sisyphean hero. Her waves and her men are her boulder.

The dudes are gone, though. Their last appearance was in 2011. After O’Neil killed them off, they resurfaced in the animated film WE, THE MASSES and in “HELL.” Inspired by Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” the sprawling triptych finds the men murdering one another, burning alive, being impaled, drowning, being ejected from a volcano. The piece took O’Neil three years to finish, and it includes 35,000 collaged elements and 65,000 figures. There is some ritualistic subtext. Raised Catholic, O’Neil may very well be alluding to pre-Renaissance altarpieces, a nice touch.

O’Neil began focusing on her guys early in her art practice. In her intricately detailed worlds that resonate with themes of catastrophe, beauty, friendship, strife, and the apocalypse, the men allowed the artist to approach narrativity through the pure language of imagery. “They’re my way of talking about the world,” O’Neil has said. “Through them, I find I can talk about anything.”

O’Neil’s visual epic stretched throughout 200 drawings, not one with a child or woman, as intended – this is a barren, frigid, heartless portion of her imagination. The end starts in 2007 with a piece owned by the Modern. In “These final hours embrace at last; this is our ending, this is our past,” the last man from the series dangles precariously from a frayed rope above a roiling sea whose waves look more like lava than water. In the short movie, the dangling man succumbs to nature. From dust to dust. Though the men have returned to her recent work, they’re larger, not as myriad, and set in abstract contexts. There are also more animals in O’Neil’s newish pieces. The results are a little cheerier and more engaging though no less throbbing with pathos.

“Once that [series] was over,” the artist has said, “I envisioned a world with no one. Empty, raw, new. I saw tectonic plates, a heated ocean, and misty beginnings. It’s my imagined version of this world without the annoyance of us humans. And, yes, after utter chaos. So I wanted it to be both the aftermath of The End and images of a new world.”

The empty terrains with which O’Neil is now entranced are “psychological landscapes,” she says. The animals that she is focusing on are realistically drawn. Juxtapose them against her men, who are cartoonish. The symbolism expands. A bird, a buffalo, and a T-Rex, all hung in succession toward the rear of the museum, are expertly rendered and, though relatively inert, lively. A little more exciting are O’Neil’s symbol-heavy drawings, featuring totemic-looking glyphs and loaded recognizable creatures. The eagle means a lot of things.

In some ways, WE, THE MASSES may seem a little aloof, a little quiet, a little repetitive, but it rewards patient viewing and draws its strength from its timelessness. We are all the men all the time.

Robyn O’Neil: WE, THE MASSES

Thru Feb 9, 2020, at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 3200 Darnell St, FW. Free-$16. 817-738-9215.