Outside his small workshop in a quiet Fort Worth neighborhood, blacksmith Shawn Beasley stood at his forge in the 95-degree summer heat. Sweat dripped from his brow as cicadas screeched from a nearby tree, but the loud insects and brutal temperature were not a deal-breaker for Beasley. He had work to do – in this case, a fire poker to form.

The 1,400-degree forge burning beside him made the heat almost unbearable. Beasley, however, was cheerful as he described his work.

“It’s the stress reliever of the century,” he said. “You get a hammer, and you get to hammer out your stress.”

Beasley has smithed for three and a half years, starting when he was 30 years old. In that time, his work has progressed from small letter openers to rings, knives, swords, and even shields.

Some people may not know that blacksmiths still exist. While a craft like this might sound antiquated, artists across North Texas have kept centuries-old artforms alive and pass on their skills to younger generations.

Weavers, spinners, blacksmiths, lacemakers, and bookbinders were typically low-paid laborers whose work was borne out of necessity rather than interest. Today, it is their love of creating that keeps these artists (and their traditions) thriving – some are even witnessing a comeback.

*****

With the popularity of the History Channel’s Fire and Forge, in which blacksmiths compete for a cash prize, Beasley said blacksmithing has slowly started to come back in style. What drew him in was the artistry – the ability to turn a piece of twisted metal into art. While Beasley had dabbled in other artforms before finding his niche, nothing fit his interests until blacksmithing. He said smithing is unique because of its ancient tradition and lineage.

“I’ve done so many mediums through high school and all that stuff with different textures of art, but this is where I’ll stay for the rest of my life,” Beasley said.

His first foray into blacksmithing was with a handheld torch and a small jeweler’s anvil in his garage. From there, his interests expanded to include a full-sized anvil, propane-powered forge, and decked-out work shed. He said he wanted to work in the most traditional forging method – coal forging – but found working with fire too time-consuming. That, and he didn’t want to worry the neighbors.

“I was always so afraid that my neighbors were going to call the cops or the fire department, because it looks like bad smoke,” he said.

Among Beasley’s favorite traditional designs are Viking and Celtic. Many of Beasley’s pieces pay homage to these traditions and include Celtic braids and Viking runes. He frequently takes his knives on the road to indie events like the DFW Witchy Bazaar.

Blacksmithing works by heating metal in a forge until the metal turns yellow and becomes malleable. Then, the blacksmith hammers it over an anvil until it reaches his desired form. For Beasley, that means his first stage sees “knives” that are blunt and shaped like a pickle.

“It’s not going to look like a knife to start out with” he said.

Once the metal cools, he creates the handle, working quickly as the metal starts to cool. He then grinds the metal down into a sharp blade and polishes to finish.

Beasley’s earliest pieces were small, lightweight letter openers forged from long nails. He progressed to smithing different types of metal and developing his own style. Today, he works with iron and tungsten steel to create knives that range from rustic, primitive-style Viking blades to smooth tools with polished handles. In a word, Beasley described his new style as more “aggressive.”

One of his more eclectic pieces is a knife called The Coffee Fiend, a halfmoon-shaped blade with a handle made of resin infused with coffee beans and vodka. The result is an unusual-looking knife with a smoky, textured appearance.

Forge Magazine says that blacksmithing is becoming more popular due to people’s desire to create something useful and unique. The author notes that the earliest evidence of smithing by hammering iron was a dagger crafted in 1350 B.C.E.

“Having something that’s an ancient way of life for so many people so many years ago, it just feels rustic,” Beasley said.

*****

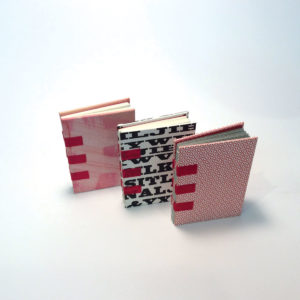

Another ancient skill is bookbinding, an artform that dates back roughly to the 6th century. Traditional bookbinding involves folding paper pages into multiple booklets (called signatures) and sewing the signatures together with a needle and thread. Once the pages are finished, the block of pages is attached to the cover – traditionally made of book board – draped in canvas-like paper or shaved leather.

“There’s nothing like holding a book in your hands,” said bookbinder Kim Neiman in a recent phone interview. “The older the book, the better it is.”

Neiman studied bookbinding at the Dallas Craft Guild, a learning center for students of pottery, bookbinding, and other skills. In 2007, she began a four-year apprenticeship with a local artist preserving art books with the Dallas Museum of Art and several universities. During that apprenticeship, Morris grew to love restoration. Now she focuses primarily on restoring worn and faded books – many of which are old family bibles.

Restoration is about bringing an antique book as close to its original form as possible, Neiman said. The method for restoring books varies depending on the book’s unique needs, yet each time the process is almost surgical. Often Neiman has to carefully remove the old glue from the book’s spine, resew the pages together, and reform the spine with new glue and tissue. The pages of old books are often soft and fragile, making restoration a delicate art.

“Sometimes people’s covers on their book will be so bad that they can’t be conserved, so then we call that ‘a restoration,’ and we try to match the covers as best we can,” she said.

The oldest book Nieman restored was from the turn of the 20th century, and she said she would be open to working with even older books.

Though it’s hard to say when the technique of binding pages together with thread came about (Nieman estimates around the 12th century), the oldest intact European bound book is the Saint Cuthbert Gospel, a red goatskin pocket gospel book constructed around 1,315 years ago. Before that, books came in the form of tablets and (later) scrolls. Arguably the oldest multi-page book in the world is the 2,673-year-old Etruscan Gold Book, whose pages are made of 24-carat gold. The construction of this book differs from later bound books, with gold rings keeping the pages together.

For Neiman, restoration is all about keeping the owner’s memories alive. At times, she said, pieces of history will fall from the pages of her clients’ books, namely in the form of mementos tucked away for safe keeping – pressed four-leaf clovers, a small bundle of flowers, tintype photos. Neiman makes a point of preserving these artifacts and returning them to her clients, many of whom don’t know they exist. She often finds locks of children’s hair tied with ribbons, floating out of the pages “like angel’s wings.”

It’s something, she said, “that’s forgotten, but it’s something that’s really important because they left it in the book. It’s really very cool.”

Neiman photographs all of the items she finds during her restorations so that she can revisit them. In some respect, she said, restoration allows her to both preserve history and to investigate it. She said one day she would like to publish a coffee table book called Between the Pages, showcasing the photos she’s captured over the years.

“There’s lots of special little things that people don’t know about,” she said, “and really only a bookbinder would know about it, because if it’s a family bible or something that’s historical, those books don’t get opened.”

When she is not restoring books for customers, Nieman said she likes to push her creativity through binding art books. Her art books often center on a political or social issue she cares about. One recent project was a set of hardcovers dedicated to the Black Lives Matter movement.

“I just want the craft to be passed on,” she said.

She said there will be a need for bookbinders as long as there are book collectors and universities. In the meantime, Nieman wants to keep bookbinding alive. And while machine-made books will not last very long, Nieman said people should store their old (particularly hand-sewn) books properly –– away from moisture and direct sun.

“I want people to know they need to take care of the older books that they have,” she said. “They’re not going to see those again.”

*****

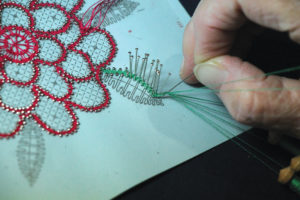

Sitting in front of her work, lacemaker Cathy Morris feels peaceful. The soft clicking sound of the bobbins turning under her fingers, combined with the steady rhythm of each twist and turn of the threads, creates a soothing experience similar to meditation, Morris said.

“The feeling of the bobbins, the sound of the bobbins as they go … there’s a lot of sensory intake,” she said, “not only seeing the lace but having it and feeling it and sensing it.”

Walking from table to table at a recent Dallas Lace Society meeting, Morris explained the history of the many different styles of lacemaking. She specializes in English lacemaking, which features tulle-like backgrounds and defined edging.

Morris has been lacemaking for 30 years. She said what captured her interest was how lacemaking allows her to “draw pictures” with thread. “Also, you have to think as you’re making it,” she said. “It’s a puzzle.”

Open-woven fabrics and netting had already existed for centuries, based on information from the Lace Guild Museum in Stourbridge, England. Meanwhile, decorative European lace was likely created around the 15th century. Shakespeare even references lacemaking, along with other yarn arts, in his play Twelfth Night, when the character Duke Orsino mentions “the spinsters and the knitters in the sun and the free maids that weave their thread with bones,” a reference to bobbin lacemaking.

Morris added that during the Renaissance, lacemaking was a cottage industry, with merchants taking a lacemaker’s wares and selling them to the nobility – the only people who could afford them. The lacemakers were mostly lower-class laborers. “Somebody was getting rich, but it wasn’t the people who were making the lace,” Morris said.

Much like weaving, knitting, and sewing, by the late 19th century, lacemaking became mechanized for mass production. While this allowed less wealthy people to suddenly afford lace, lacemakers – unable to compete with the flood of cheaper products – were forced to find work in factories or other industries. Since then, bobbin lacemaking is no longer about serviceability. Lacemaking is a labor of love.

Crafting lace is a time-intensive process, with even small projects sometimes taking tens of hours to complete. One of Morris’ current projects is a white bird crafted in honiton lace. If she had to estimate how long it will take to complete, she said it’s around 80 hours of work. The thread is so fine, she wears two sets of glasses while working.

Morris said lacemakers don’t usually count the hours when they’re working. Instead, they’re enjoying the process.

There are different techniques for making lace. Morris predominantly makes bobbin lace, wherein bobbins holding thread are methodically crossed one at a time, much like braiding. The patterns vary in size, as do the thread and bobbin sizes. The finer the thread, the longer a pattern might take to complete. Often lacemakers will pin their work to a stiff pillow and cover it with fabrics to keep the bobbin from becoming tangled between sessions.

Morris said lacemaking is a skill that should be preserved, both because of its history and the beauty of the work.

“It’s got a lot of history,” she said. “It’s just beautiful.”

And while all crafts wax and wane in popularity, Morris said she is confident lacemaking will come back in style –– eventually.

“It was very popular in the 1970s and ’80s … and I think it will come back again as people re-discover it,” she said.

*****

It was exciting to visit spinner Evelyn DeWitt and watch her spin yarn from her walking wheel. As a spinner myself, I had always wanted to see one in action. A walking wheel is a tall spinning wheel that is so large the spinner has to walk back and forth to operate it. Some estimates say that early spinners walked more than 20 miles each day while spinning yarn.

DeWitt allowed me to try the wheel, and it was immediately clear that spinning this way is tricky. Multitasking is a major component to working with a walking wheel, since you must walk back and forth to maintain tension, spin the roughly 5-foot-tall wheel with one hand, and draft (gradually separate) the fiber with the other hand. Despite the challenge, there is an overpowering Old World feel to spinning this way that makes a spinner’s heart giddy.

DeWitt, a self-taught craftswoman, started spinning in 1989, the year she bought her first drop spindle. As a traditionalist in every sense of the word, she said spinning was a natural fit for her lifestyle – her house is filled with antiques, the yarns she spins are dyed with plants, and she tries to learn the “old” way of doing every craft.

“I like history,” she said. “I like old things that still work. I always have.”

She quickly became passionate about spinning and bought her Great Wheel in the early 2000s, when she spotted it in the window of a local antique store. Despite the logistical challenge of strapping a Great Wheel to the roof of her smart car, she managed to haul it home. She now has a wheel that is too large to use in her tiny house, keeping it disassembled until she can operate it in her backyard.

DeWitt said spinning on her Great Wheel makes her feel connected to the craftswomen who came before her – women from different countries and cultures connected through art.

“It’s like time travel,” she said of spinning.

She said what makes spinning meaningful to her is the way it makes her slow down. By spinning in her garden, she can take a moment to pause, be with nature, and listen to the birds. As she said these words, we watched a red-winged blackbird perch on her fence. “There’s a quietness that you can get from doing these things,” she said.

Weavedesign.eu says spinning dates back roughly 20-30,000 years, when early man started to create string from twisting plant fibers together. Spinning was then done with sticks and, even later, spindles. By the time spinning wheels were invented, women were already spinning as a livelihood (which is where the term “spinster” comes from).

While she can’t say for certain when her Great Wheel was made, DeWitt said it is definitely an antique.

Her style of spinning seems to describe her general philosophy on life: homespun.

“I love plain and simple and serviceable,” she said.

She added that no matter one’s skill level or craft, it is the process that makes art powerful.

“It’s good for your heart,” she said. “It’s good to create.”

*****

Fiber artist Kristen Cathey is a Jill of all trades when it comes to yarn. Like many serious fiber artists, Cathey started with one craft and couldn’t resist trying new projects.

“I’m a spinner, a knitter, a crocheter, I dye yarn, I felt things – you name it, I probably do it,” she said, smiling.

The atmosphere of West 7th Wool was casual and cheerful when I met with Cathey to talk about her latest interest: weaving. Cathey works at the shop and looked very at-home sitting on a little white couch and working at a small loom. The mechanics are pretty straightforward. She interweaves yarn between columns of vertical threads (called the warp), smooths out her new row (called the weft), and starts again from the other end. The material is surprisingly light yet sturdy.

While knitting or crocheting would result in a chunkier, more stretchy material, it also takes more yarn. What drew Cathey to weaving was her desire to save some of the yarn she’d worked so hard to spin and to put her finished yarns on display.

“When you become a beginning spinner, you make a lot of samples of things … and from spinning, I was only producing 50 yards here, 50 yards there, and I’m like, ‘I can’t really knit anything with that of a size I would enjoy,’ ” she said.

Cathey’s other projects are displayed on the walls at West 7th –– abstract pieces involving numerous textures, colors, and hanging threads. She also makes scarves and bags, and her creativity is clear in every piece.

“There’s a lot of different styles of it, and it’s very intuitive,” she said of weaving. “There are some tapestry styles and freeform styles that are very much like painting with yarn, and so you can kind of be in the moment and play with colors and textures just like an artist does on a canvas”

Wall art like Cathey’s has become trendy in bohemian-style interior design, coinciding with the reemergence of macramé plant hangers. Cathey said she has seen weaving become gradually more popular, which inspired the staff at West 7th Wool to start offering weaving classes this year. Cathey teaches the class, and the shop supplies looms for students to practice on. She said weaving is much easier than it looks and that people should not let intimidation keep them from trying it.

“Once you get past the warping, the sky’s the limit,” she said.

Weavedesign.eu says that weaving is one of the oldest surviving crafts and dates back to the Neolithic period (about 12,000 years ago), long before the shuttle loom was invented in the 1700s.

Today, with mass-produced woven fabrics readily available, Cathey said people are starting to return to weaving and other fiber arts. She believes this reflects a wider rejection of globalization and that people now want to have a personal connection to the product.

“It’s one of those things where it’s in our everyday lives, but we don’t always think about it,” she said of woven products. “Somebody had to make your T-shirt or weave the fabric for your pants. It just tends to be a factory and not a human these days.”

Since weaving is a repetitive task like knitting and spinning, Cathey said it allows the weaver to settle into a comforting rhythm and de-stress.

“When you’re working at one of the rigid heddle looms, you get into a certain kind of rhythm … so it just becomes like a dance,” she said. “A waltz, if you will.”

While their artforms, techniques, and styles differ greatly, one thing binds these local artists together –– their love of craftsmanship. When asked what readers should know about Old World artistry, DeWitt said, “Just know the old life. Learn a few old ways. You might be amazed at the adventures it can take you on.”