Well, we’re finally there. Hemp, marijuana’s male counterpart, which does not make you high, was legalized nationally earlier this year. The passage of the 2018 Farm Bill removed hemp with very low concentrations of THC, the substance in marijuana that stones you, from the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Controlled Substances Schedules, which will allow the plant to be grown legally in the United States for the first time since World War II. We’re probably looking at some years for the plant with a thousand uses to be completely integrated in the farming system, but the first commercial crops in Texas should go into the ground next spring. And while Texas’ Commissioner of Agriculture, Sid Miller, admits Texas is a late bloomer — because the state did not join in experimental hemp plantings that were permitted under the 2014 Farm Bill — he predicts that we’ll not only catch up quickly but that we will soon be the leading grower in the country.

“When Texans go all in, they go all in,” Miller told me.

Why is the legalizing of commercial hemp important? Because of the ways in which it can be used. Its stalk is thick and woody and can grow to about 20 feet tall. Its fibers grow the entire length of the stalk. The stalk and the hurds, the material on the inside of the stalk that embodies the fiber, can be made into everything from building materials to insulation, from fine horse bedding to biodegradable plastics, from boogie boards to particle boards. The fibers can be spun into fine textiles and strong rope that is resistant to both mold and rot. The leaves and seeds can be pressed into CBD oil, which is used for everything from alleviating anxiety and depression to preventing inflammatory arthritis and as a sleeping aid. Topically, the oil is used as a pain reliever and muscle relaxer, among other things. It’s already used in sun blocks and Dr. Bronner’s soaps, and its seeds are sold in health food stores and supermarkets for their high concentrations of essential fatty acids.

For farmers, hemp is a potential gold mine because it can be planted on land that’s taken a beating and can help fix nitrogen into the soil. For environmentalists, it’s a dream because the pulp from a single acre of hemp can produce as much paper and fiberboard in a year as five acres of trees. And we all loved those Adidas and Nike hemp sneakers.

The only problem is that until 2014, when the Farm Bill allowed limited experimental hemp crops at universities around the country, all of those hemp products were made from hemp grown in Canada, China, Romania, and other countries where its utilitarian value was not criminalized. Here in the United States, it wasn’t so long ago that Gen. Barry McCaffrey, then President Bill Clinton’s drug czar, was demonizing hemp and prohibiting the importation of hemp products from Canada. His most famous line on the subject came in the late 1990s, when he told a group of high-ranking DEA and Customs and Border Control officials that hemp products had to be banned because “kids are boiling down their hemp shirts and mixing the essence with alcohol to make marijuana.”

Though the scenario put forth from McCaffrey was complete nonsense and is hilarious in retrospect, given his position and history, a lot of people believed him. That attitude probably kept the United States from joining Canada in commercial hemp production for the last 20 years.

Moving from “boiling down hemp shirts” to make marijuana to complete legalization was a difficult political climb that involved a lot of work from a number of people.

*****

In 1993, longtime hemp activist Eric Steenstra and Steve DeAngelo, another longtime hemp and cannabis activist, started a company called Ecolution that made hemp jeans, shirts, and accessories from 100-percent hemp. Their materials came from Hungary and Romania, which wouldn’t have been their first choice for hemp, but China, their first choice, was fresh off the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacres in Beijing, where the government crushed protesters who were demonstrating for political and social reforms, with tanks. “We could not do business with China because of that,” my old friend Steenstra told me recently.

The jeans made by Ecolution took off, and soon their shirts, hats, bags, and other hemp products moved from music and hemp festivals and were being seen in stores nationwide. International companies like Adidas were making lines of hemp shoes and clothing as well.

By the year 2000, both Steenstra and DeAngelo had moved on from Ecolution. They sold the company in 1999 after reaching $3 million in annual sales. DeAngelo moved to California and opened Harborside in Oakland, one of the first six medical marijuana dispensaries to be licensed in the United States, among other businesses. Steenstra stuck with hemp and founded the nonprofit Vote Hemp in 2000, whose mission was to legalize hemp as an agricultural crop in the United States.

“It took a while,” Steenstra told me recently. “We didn’t get the first hemp bill introduced by longtime Congressman Ron Paul until 2005. Vote Hemp helped draft that, and then we started knocking on doors in the House to build up sponsors for the bill.”

Most of that was trying to educate members of the House about the economic opportunity that farmers and businessmen were missing in the United States while hemp was imported from China and elsewhere. “A lot of people thought cannabis was a dope or rope issue,” Steenstra said. “You could get high from the female plant, or you could make ropes from the male plants. We had a lot of work to do.”

Seven years passed before Vote Hemp — other groups lobbied as well but not with the singlemindedness of Vote Hemp — persuaded Oregon’s Sen. Ron Wyden to introduce a hemp bill. Neither Paul’s House bill nor Wyden’s Senate bill gained immediate traction, but they inspired Congress to start talking and learning about the issue.

By 2013, when Congress was working on the Farm Bill, Vote Hemp was working with Rep. Jarod Polis from Colorado, “and Polis put in an amendment that would allow Colorado State University to grow an experimental hemp crop,” Steenstra said. “At the same time, we had a resurgence of interest in hemp in Kentucky. There was an agriculture commissioner who won an election in 2013 by running on ‘bring back hemp for the farmers.’ Well, that got the attention of Sen. Mitch McConnell, who would not talk with us for years — until he realized his constituents saw the benefits of hemp and wanted to plant it. Once he realized that, McConnell did a 180 on the issue and worked with us and worked in conference committee to reconcile the Polis and Wyden bills to add departments of agriculture, universities, and a pilot program to the final bill.”

So rather than just Colorado State University, universities and state agriculture commissions all over the country were allowed to apply for licenses for experimental hemp crops. Of particular importance in the passage of the hemp amendment that was eventually included in the 2014 Farm Bill was the pilot program encouraged by Vote Hemp that McConnell included. “The pilot program was intended to study the commercial value of hemp,” Steenstra said, “and that really got things moving, in terms of generating interest in growing hemp, and was what ended up on then-President Obama’s desk when he signed it into law on February 7, 2014.”

There were still hurdles to leap, of course, as when the Kentucky ag commissioner tried to import hemp seeds for research and the DEA held up the shipment. But with persistence and insistence, the shipment finally got through and the experimental crops were planted. In all, more than 3,500 experimental hemp crop licenses have been granted since that bill passed, and the first official hemp crop report was released in 2016, when nearly 10,000 acres were grown in 15 states. That number jumped to more than 25,000 acres in 2017 and 78,000 acres last year, grown in 23 states.

But Texas was not among them. Part of that was Miller’s reluctance to spend any political capital on the issue. “I am an historian,” he told me, “so I knew years ago that a lot of our founding fathers grew hemp, including Washington, but there was no sense in pushing it when it was illegal on the federal level. Now that that has changed, well, I’m all for the farmer, and if we can get another tool for them, that’s great.”

Texas did not come in easily. Even when the 2018 Farm Bill made hemp growing legal by removing it from the DEA’s Controlled Substances Schedules, Texas law still maintained that it was on the state’s Controlled Substances Schedules. That changed when the Texas Department of Health Services was sued by the ACLU and others to rectify Texas law, which stipulated that state law had to be consistent with federal law on that issue. In a letter to Jonathan Miller, a lawyer involved in pressuring Texas to legalize hemp, Stephen Pahl, associate commissioner of the Texas Consumer Protection Division, wrote, “Based on requirements in … the 2018 Farm Bill and Health and Safety Code … Dr. John Hellerstedt” — commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services — “signed an amendment to the Texas schedules of controlled substances, removing hemp from the schedules. The de-scheduling is consistent with federal law and the obligations of the commissioner.”

Ag commissioner Miller said that despite hemp’s official legal status, farmers can’t just go out and start planting. “Right now, I’m waiting on the federal government to come out with guidelines for the state to grow. I should get those in October or November. Then it’s up to me to write our rules for Texas. Then I’ll publish them, then I’ll have to send them to Gov. Abbott, our attorney general, and the federal government for approval. If that all works, I can start issuing licenses to actually grow hemp. Hopefully, we can get things ready for spring planting.”

And what does he think Texas farmers will grow hemp for next year?

“Most people are just using the buds for CBD oil,” he said. “I don’t think people will be growing it for stalk and fiber and so forth. We’ll get to that soon, though.”

*****

One of the people very excited about hemp legalization in Texas is Tim Blackwell, owner of Zen Alchemy Labs, an online CBD store. He recently told the Weekly’s Edward Brown that he has 25 acres of Tarrant County property designated for hemp cultivation. His store sells a wide range of CBD products, ranging from topical treatments to vape pens and nutritional supplements. All of his products are tested to ensure that the CBD levels match what the manufacturers claim and that there are no pesticides present. “But it would be better to grow it ourselves,” he said. “If we can get to produce hemp that has no solvents, heavy metals, pesticides, or microbials, we wouldn’t need to buy it. We want [our products] to be as close to the earth as possible.

“Our hope is that my dad and I can start farming hemp. It will take two or three months just to get the land prepared, but we can’t do anything” until it’s licensed, even though it’s now legal.

But Blackwell isn’t the only person interested. Brown recently attended a hemp presentation at the Northside’s Elks Lodge, where the Republican-leaning crowd came to hear about hemp in a program hosted by Project Fort Worth, an organization that works to inform voters on local issues. Among the event sponsors were the Arlington Republican Club, Republican Women of Arlington, Tarrant County Young Republicans, and Northeast Tarrant County Young Republicans.

Two large tables overflowed with hemp-derived products, ranging from non-intoxicating edibles and ointments to fabrics and soaps. Coleman Hemphill, the executive director of Texas Hemp Industry Association, a nonprofit representing the hemp industry whose mission is to promote hemp products throughout the state, was one of two speakers on the program. He talked history.

“Hemp has played a huge part in the history of the U.S.,” he said. “The first two drafts of the Declaration of Independence were drafted on hemp. We used hemp in our canvas and parachutes during World War II.”

As he spoke, the screen behind him displayed an advertisement from a mid-20th-century magazine that read, “Hemp Grows Luxuriously in Texas.”

One of the issues Hemphill brought up was the matter of keeping the THC levels below .3 percent, above which is not legal for hemp. Some states, he said, have already addressed the issue. “In Oregon, the regulatory department comes out” and tests hemp crops. In Texas, he said it would be the same. Samples will be taken by the agency charged with hemp regulation. Those samples will be sent to a lab to determine the levels of CBD, THC, and the other chemical compounds found in all cannabis plants. Those samples found to have a THC content higher than .3 percent, Hemphill said, will probably be destroyed, at the owner’s expense.

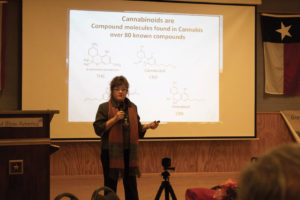

The second speaker of the evening was Sheila Hemphill, Coleman’s mother and the policy director of TXHIA. Among other things, she addressed the public misconception between CBD and THC. “Cannabinoids are the family of chemicals found in hemp and marijuana,” she said. “And there are more than 80 of them. God created all animals with an endocannabinoid system. We were designed to be nurtured from them. Our receptor sites are primarily in the brain and nervous system.”

Marijuana is cultivated to produce large amounts of THC, which gets you high. Hemp is pushed to produce high levels of CBD and very low levels of THC.

During a Q&A session following the presentation, one attendee asked if you could hide marijuana in a hemp field.

Sheila took the question and replied that you could certainly hide marijuana in a hemp field, or a cornfield, or any field you liked. “But a hemp field is the last place where a grower would want to hide it, because no one wants cross-pollination. Marijuana growers surely don’t want pollination from the hemp plant, which would destroy their THC value and produce seeds in their crop. And hemp growers do not want their crops above the .3 percent THC threshold.”

Texas State Sen. Charles Perry, the primary author of the Senate-side hemp bill that was reconciled with a House bill and signed by Gov. Abbott on June 11, fully legalizing hemp in the state, spoke with Brown shortly after the presentation. “We worked hard to include a number of consumer protection provisions throughout the bill to ensure all products are safe and THC levels in hemp stay below the legal limit,” Perry said. “It is projected the market for hemp-derived products will exceed $20 billion over the next five years. This is a big deal for rural Texas and our economy.”

*****

$20 billion is a lot of money and represents a lot of hemp products, something that was unimaginable just 30 years ago. Few people even knew the word “hemp” back then, or if they did, they knew its historical use. But a rambunctious man named Jack Herer, now deceased, collected old accounts of hemp’s uses and produced a broadsheet that he touted on the Santa Monica pier in California. Herer’s friend, Capt. Ed Adair, told him he ought to put everything he collected into a book about hemp that he could sell, and in 1985, he did just that, publishing The Emperor Wears No Clothes. In its pages were copies of articles on the accounts of hemp use, from being an element in oil paints to the hemp canvas used on the Conestoga wagons and prairie schooners that opened the U.S. West. And hundreds of other uses as well. In World War II, the federal government encouraged farmers across the Midwest to grow it for the war effort, as the supply of jute from manila was choked off. There were articles on the potential use of hemp to replace fossil fuels and trees for paper, which could help reverse the Greenhouse Effect (now Climate Change).

While the early editions of the book eventually made it into the hands of several editors — myself included, in small part — who eliminated some of the more dubious material, with Herer’s unflagging energy, the word about hemp began to circulate. High Times magazine began to talk up hemp, and European countries like Hungary and Romania, as well as China, which had never stopped utilizing hemp for textiles and other things, drew the interest of hippie entrepreneurs, who sought that material to begin making products to sell throughout Europe and here in the United States.

One of the early believers in the value of hemp was Debby Goldsberry, who was present at Hash Wednesday, an annual spring event at the University of Illinois at Urbana. Goldsberry, who was a founder of the hemp-education group the Cannabis Action Network, was there in 1989 when, she told me recently, “police beat up protesters. They, the police, vowed the event would never happen again, but not only did it happen, right after they vowed it wouldn’t, a group of us went out on the road and held rallies at other universities in Illinois.”

Among those present were the late Ben Masel, the founder of the Great Midwest Harvest Festival, a pot affair; Steve DeAngelo; and Jon Gettman, then executive director for the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws.

Goldsberry, who went on to become one of the most important activists in the medical-marijuana movement, said that the tour was so successful that the group decided to go on another tour in the fall. “We traveled to five states for that tour,” Goldsberry said, “and we centered it around the Great Midwest Harvest Festival.”

During that tour, a young activist, Maria Farrow joined and became one of the group’s core members.

The tour was also successful and led to a decision to embark on two tours a year by the group — which named itself the Cannabis Action Network after the initial tour — concentrating on hemp education. Jack Herer, who had been doing his own hemp tour in California, soon joined the group, which had Herer’s book, and a good grasp of hemp’s uses, but little in the way of hemp. “We had people do advance work who would organize good local venues,” Goldsberry said. “Sometimes, it was a festival. Sometimes, a university debate. And we’d show the people who attended our little pieces of hemp cloth, old hemp books, and things like that. And people were getting their minds blown because no one had any idea how vital a crop hemp had been and how diverse its uses were.”

The first legal hemp product that CAN ever obtained, Goldsberry told me, was “a Western-style denim hemp shirt that Willie Nelson produced. We got a bunch to wear and some to sell, and we used the proceeds to move the tour to the next location.”

Another woman, Monica Pratt, soon joined the tour, and the three women came to be recognized as the face of CAN. “We became the core of CAN, but there were other people involved like Doug McVey and Rick Frommer in support roles and then our superstars: Jack Herer, Ben Masel, Steve DeAngelo, and Steve Bloom,” — my old compatriot from High Times — “who would mentor us, give speeches on the tour, and things like that.”

The point of the tour was to build local educational organizations in most major college towns and major cities all over the United States. “And we had done that by 1996 when we came off the road,” Goldsberry said.

They certainly had. By 1996, hemp products were for sale all over the country, and Herer’s book, currently in its 12th edition, had sold in the millions. News programs and major newspapers and magazines had run major stories on hemp: The plant was no longer thought of as only the “rope” in the “dope or rope” equation.

The same year that CAN quit touring — with Pratt joining an organization called Families Against Mandatory Minimums, Farrow moving to New York to become a fashion model and part-time hemp and cannabis activist, and Goldsberry moving to California and opening the medical marijuana dispensary, Berkeley Patients Group, in 1999 — a marijuana breeder in Holland named Ben Dronkers decided to give hemp growing a run. He paid several Dutch farmers to plant the crop, paid them for growing it, and guaranteed them a fair price for it whether it grew or not.

It grew. It grew to nearly 20 feet tall. And that was a problem. It turned out that there were no farm machines that could handle either the thickness of the stalk or, when the stalks were rhetted by hand, the length of the fiber. At the time, he told me he thought of giving up but decided instead to have the farm machines reengineered to handle the product. It worked. He’d made hemp a viable farm product in the modern world, where there were few people willing to do the work of separating stalk from fiber by hand.

People who know hemp understand that the farm equipment needed for it, as well as the industrial processing plants to make the array of products that can be manufactured by the plant, are not yet in place. Most of the products on the market are either made in other countries to U.S. entrepreneur specs or made here by niche companies. And to be fair, the demand for hemp bricks and insulation, and even particleboards or degradable plastics, simply does not exist yet.

But the demand for CBD oil exists, which is why Ag Commissioner Miller said that’s what he thinks the early Texas hemp farmers will aim to produce. “About a dozen processors have gotten in touch with me,” Miller said, “and most are starting with the oil. But they will expand to the fiber and other things as well, sooner or later.”

Miller is concerned about having too many farmers jump on the CBD bandwagon, however. “I tell farmers not to grow this on speculation. Not one seed without a contract, because if you tell a farmer he can make a profit from a crop, he’ll plant the world with it and have to give it away because he grew too much.”

And no, he said, the farmers will not be growing the hemp on marginal lands. “I don’t think we’ll start growing it on poor land,” he said. “I think the farmers will have a big investment in this and they’ll want to hit a home run right off the bat. They’ll plant it on their best ground. They’ll irrigate it, the whole thing, particularly in the first year or two, because people are talking about earning $3- or $4- or even $5,000 an acre from this, and that’s a lot of money. Now further down the line, if we get to full commercial production, well, then I see it as being an excellent rotational crop, particularly for its ability to set nitrogen into the soil.”

Asked to speculate on how many farmers might plant next year, Miller didn’t know for certain. “It depends on how regulated it is, I think,” he said, “but I could see 5,000, 10,000 people asking for permits.”

And when the inspectors find that someone’s crop is a touch too high in THC? “We will be certifying all hemp seeds,” he said, “but if we go out to sample and a farmer’s number is high, he’ll have to destroy the crop. I do not look forward to that day. I will not be a very popular guy.”

With additional reporting by Edward Brown.

Peter Gorman, can you show us in scientific studies where the experts state that Hemp is the male cannabis plant? Thanks in advance for correcting your ignorance.

Hemp is not marijuana’s male cousin as stated in the piece above. You’re readers deserve to be informed with accurate information.

Hemp isn’t new to Texas. It’s only been prohibited for the last 40 or 50 years. Before that hemp was grown all over the nation. Why was hemp made illegal? Primarily because it interfered with giant International corporations like Hearst and Dupont that found that hemp fiber was competing with their business interests. Because these giant corporations didn’t like the competition from hemp the entire United States was prohibited from growing it. Until we get corporations out of control of our government we will never be truly free again.

First and foremost: Hemp is not marijuana. Marijuana is not hemp. This is one of the most important facts to KNOW AND SHARE because people are unaware that they are different. Oftentimes people believe that hemp is the male plant of marijuana. This is false.