A key feature of Diane Durant’s creative process caught my attention as I stepped into her Monticello abode and work studio. In lieu of vases, cookbooks, and other bric-a-brac, her living room held carefully hung mementos of her past, including a slide projector and child-sized clothing.

“I like to surround myself with family relics,” Durant said, noticing my curiosity. “I like being surrounded by things that tell stories.”

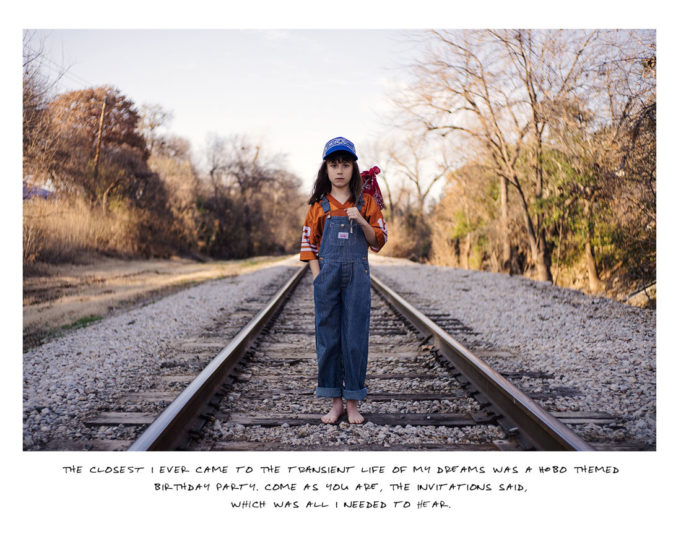

Many of those stories, and more than a few of the multidisciplinary artist’s family relics, have found their way into Durant’s newest photo book, Stories 1986-1988, which will be published by Daylight Books, a nonprofit dedicated to publishing art and photo books, this fall. Durant, who has already published several photo books, is currently finalizing the book’s layout. The photo series captures images that are set against familiar North Texas landscapes and feature the artist’s pre-teen daughter dressed in 1980s attire. One photo captures her daughter with a red scarf bindle slung over her left shoulder. She stares down the train tracks and right into the viewer. Text accompanies each image. This photograph reads, “The closest I ever came to the transient life of my dreams was a hobo-themed birthday party. Come as you are, the invitations said. Which was all I needed to hear.”

Durant said she spends a lot of time reflecting on her life and the forces that have shaped who she is today. Old photographs, memorabilia, and memories (whether true or false) all inform one’s “personal mythology,” she said.

“When I was 8, everyone came [to my birthday party] dressed as a hobo,” she recalled. “I think that kid [back then] was probably funny. I see [those quirks] in my daughter.”

Durant didn’t expect the biographical photos to have photo book potential. She began the series in late 2017, partly as a way to process events from that time in her life but also as a way to connect with her daughter through photography. The editor of Daylight Books found the images on Durant’s webpage and asked Durant if she could create enough work on the subject to fill a photo book.

“They are my memories,” Durant said. “Conceptually, you can appreciate the story being told. It is very much from the ’80s. The outfits and references are relatable to my generation: roller skating parties, Toys R Us, Cabbage Patch Kids. Some of the images are funny.”

This year has been defined by two ambitious projects. In addition to Durant’s photo book, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art recently included Durant as one of four artists (along with Christopher Blay, Lauren Cross, and Arnoldo Hurtado) for the launch of Carter Community Artists. The year-long program is dedicated to “working with and supporting local artists with the goal to create opportunities for the North Texas community to connect with the museum’s renowned collection and artists in the region,” according to the Amon Carter. Durant said the museum has been open-minded about programming suggestions from the four resident artists.

“The Amon Carter said yes to potential,” Durant said. “Nothing, program-wise, had been set in stone.”

So far this year, the resident artists have led workshops, drafted brochures for use in the museum, and overseen community projects outside the museum’s confines. Durant has written poems based on works of the Amon Carter’s permanent collection. She said the group has discussed the idea of creating a community event in underserved areas of Fort Worth called Party on Your Porch, a play off the museum’s regular live concert, Party on the Porch. While the details haven’t been hashed out, Durant said it will be a “whole different way” for the Amon Carter to engage with the community.

“I feel like the Amon Carter is putting its money where its mouth is” with the Carter Community Artists program, Durant said.

The University of Texas at Dallas professor, mother, photographer, and Carter Community Artist joked that the first thing she plans to do after her photo book comes out is to take a very long nap. Whatever her next project is, Durant said the venture will probably start with a concept.

“I’ve grown as a storyteller” through my recent work, she said. “I’ll start with a script in my head. I don’t know what I’m going to get [by the end of that journey]. A lot of my ideas come from ridiculous conversations that start with, ‘Oh, you know what’d be funny?’ And then I go from there.”