Jason Brimmer remembers the first time he saw the Mountain. The Fort Worth husband, father of two, and photographer was sitting at the corner of Lancaster Avenue and Riverside Drive watching as a steady flow of people headed in and out through gaps in a nearby fence.

“Others slipped into the tree line, disappearing through a dense tangle of green,” he wrote in an email to me. “Others climbed up a steep rock nearly 20 feet above the ground. All were headed toward an area I could not see from my vantage point, so I followed them and found their camp … indistinguishable from any other camps I’ve seen.”

Jason, or “Red” as the Mountain residents call him, because of his red hair and beard, has been filming the life of Fort Worth’s homeless for the last several years. He recently learned that Code Compliance had posted a formal notice to vacate the Mountain by April 22. The entire hillside would be leveled, along with any belongings left behind.

Red recently invited me to accompany him to the camp to speak with a few of his acquaintances.

On a cloudless morning in late April, he and I parked in a little enclave on East Avenue, just off Riverside on the East Side. It was 8:30 a.m. when we walked across Riverside and entered through an open-chain gate into the camp. The Mountain, located on the southwest side of Riverside and Lancaster, began hosting its first occupants earlier this year after several other nearby camps were shut down by the City.

Red is not only my guide this morning. He is also my new friend. Red introduced me to Bruce, Chris, Magik Mama, Michelle, Shelly, Tonka, and Veronica. Visiting a camp is very different — more haunting, more forbidding — than speaking with the homeless at the downtown library, at the Presbyterian Night Shelter, or even on the street, which is what I did in researching my last article for the Weekly, “Faces of Homelessness” (Nov. 28, 2019).

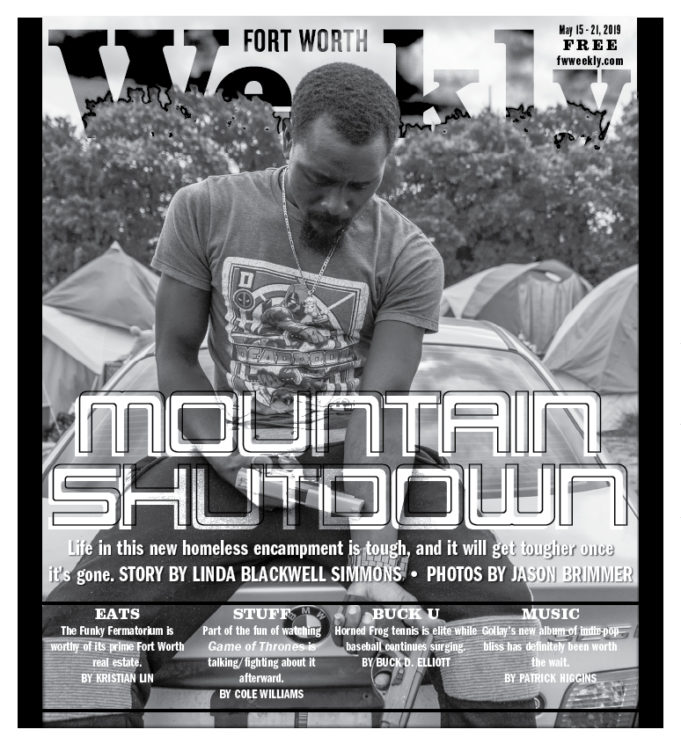

The homeless population on the Mountain has been steadily growing, with approximately 60 tents this particular day, separated into a handful of distinct clusters. Red educates me on the politics of the camp. Every cluster has a leader, and often there is conflict among the clusters.

At the first group of tents, I met Magik Mama, a woman who could not stop talking, and although she was speaking English, I could not understand a word she said. What came through clearly was her anger. Michelle, 24, a transwoman on her own since age 14, refers to her father and grandmother as devils because they hate gays and alternate lifestyles. Suffering from a genetic disorder — Charcot Marie Tooth, a rare disease that affects the nerves — she spoke of her depression and numerous attempts at suicide. Chris and Tonka, whose tents are pitched apart from the others, also shared their stories. Chris explained why so many residents stay in the camp all day instead of trying to find work — someone has to guard the camp. Theft is common and can happen in an instant, especially theft of medical supplies. Tonka, moving from one foot to the other, obviously high on something, pulled a gun from his baggie pocket and pointed it to the ground behind him — a showoff gesture, Chris told me. It turned out to be an air gun. Tonka talked about the camp chickens disappearing one by one, his grill ending their own dreadful hunger. Stories of women being sexually assaulted are common here, but Bruce talked about how men are also victims of sexual predators.

Shelly, an RN and the one who at first appeared to have the most hope, occupied a makeshift tent with her husband, a caged duck, and three abandoned newborn kittens that she was bottle-feeding. A few days prior, she had discovered her friend in a nearby tent had died the night before. The City came to take away the body. “I wonder what they do with us when we die?” she asked. “Our bodies, I wonder where they take us?”

She spoke of plans that she and her husband had to get out, to find jobs, to go back to that place in West Texas where a friend lived, but on top of the Mountain, still shaken from finding the cold, pale body of a friend, she seemed to know, to be sure, that she was not going to leave. There would be no job, no trip back to West Texas. She was convinced they would die on the street. I asked her what she thought the solution was, and she turned toward her tent and said, “This is.”

A homeless camp is not a place where one wants to stay very long, but Red was at my side the entire visit. He spends most of his free time at the Mountain.

Born in Nashville to a father who practiced psychiatry and a mother who taught school, Red fell in love with exploration and photography early.

“It is because of my mother’s love of history and literature that some of my earliest memories are of pulling down slim, yellow-backed National Geographic magazines and poring over the pictures,” he said. “When I was growing up, Nashville could be a dangerous place, especially downtown, where the homeless community was very visible. There was not a single overpass in or around the city that did not have a homeless camp. I remember being hurried down the street in front of my father’s downtown office, pushing past open hands and crumpled, yellowed cups as they were shaken, the holders asking for money.”

Red’s grandfather grew up during the Great Depression and, with nothing more than a third-grade education, built a dark room with scant supplies.

“We would crowd around his dinner table with a box of old black and white photographs, looking at pictures of poor children standing in clothes made from flour and potato sacks, bare feet on bare soil,” Red recalled. “My grandfather’s family was so poor, the family legend goes, that they didn’t know a depression had hit, let alone a great one. At the bottom of that cardboard box were other pictures, dark pictures from the war, many my grandfather had taken — groups of boys with lean faces, fatigue shirts sweat-stained and opened against the jungle heat, clustered inside a barrack. Names had been scribbled on the backs and in the margins. Some were of men in ditches, surrounded by smoke and ash and fallen palm trees, burned beyond recognition.”

Red told me this is how his love of photography began — in a house where a person’s inner world was to be studied, surrounded by the great works of English literature together with piles of National Geographics and a grandfather who had survived the worst poverty that had ever befallen America, in Nashville, a town with an ever-present homeless community.

Upon moving to Fort Worth in 2000, he landed a job at Starbucks in White Settlement: “Morning after morning, I would return, inertia controlling me, so I stayed, working behind the bar, making macchiatos, frustrated and getting bitter.”

Then one morning, fortuitously, or perhaps it was meant to be, a customer left a Nikon D7000 on a table. The camera went into lost and found, where it waited for almost three months for its owner to claim it. During this time, Red bought and read every photography book he could find.

“I had all the technical knowledge that 32 pounds of books — yes, I did weigh them — could provide,” he said. “As I stood in the backroom of that Starbucks holding that Nikon, I realized I had no subjects to photograph, so I decided to head to Lancaster Avenue with my new camera, the first time I had ever been in that part of town. I arrived on the scene having been raised on The Grapes of Wrath, Down and Out in Paris and London, and my grandfather’s photography. What I found was not a poverty created by economic disaster or some kind of mysterious oppression but a poverty created by the complete and utter destruction of whole communities.”

Red said he is often asked what he believes the solution is. What can be done to help the homeless?

“I always assume these are rhetorical questions so that we can all frown and shake our heads at the great tragedy of it all,” he said. “After all, it can happen to anyone, we say. There is a pattern at work, a kind of common ancestry that resides among almost every person living and dying along Lancaster and Riverside. After four years walking the streets and trails and camps, after taking thousands of photographs, I know the Lancaster family history so well I don’t even have to ask how they got here. It usually starts with stepfathers. ‘My mom moved this guy in.’ Mom starts to ignore her kids while busy with her new man. Then the abuse progresses from verbal to physical to sexual. I am always struck by how nearly identical their earliest memories are. Mac ’n’ cheese always plays a role. Mom was not waiting for her kids to come crashing through the door after school. Instead she was in bed, hungover since morning, reaching for what little was left in the bottle. One Lancaster girl told me how, at the age of 6, she had never had a home-cooked meal. She cooked boxed macaroni for herself and her little sister every day, once spilling a pot of boiling water on her dog. Yes, sadly there is always a dog around.

“The macaroni kids,” Red continued, “are the lucky ones. Others were sat down around low coffee tables to watch as meth is cut, weighed, bagged, and sold by their parent. I think about Debbie, who told me her mother was 13 when she was born and finishes her story with body-shaking, heaving sobs. The anger, the hate, the pain is unbearable, and the shame is still fresh, nearly 40 years later — as she recalled being sold to trailer park child molesters when she should have been in second grade learning multiplications tables.

“I have sat and listened as scores of women tell me how they have been beaten and raped on the streets around Lancaster,” Red continued. “I have photographed their black eyes and swollen faces. I have watched a teenage prostitute use a thin sliver of shattered mirror to touch up last night’s make-up before rummaging around in her bag, looking for a hat to cover her hair, which had begun to fall out in clumps — bad nutrition and meth. Not long ago, I met a man who had been shot in the belly with a shotgun. The blast obliterated most of his stomach, leaving his belly skin hanging loose, the holes from the pellets still oozing.”

Red said he has tried to track down what happens to the homeless who die on the streets of Fort Worth, but it is difficult to obtain information. He tells me of Peanut hit by a car. Then there was Cici, beaten until brain dead.

“I have unfettered access to any camp in Lancaster, most of Stop Six, and all of Como,” Red said. “I’ve documented how the homeless live. It only seems appropriate that I also document how they die. I do understand the position the City is in. I know full well the kind of lawlessness that can erupt in these camps.”

A manager from Code Compliance promptly answered my inquiry as to the specific reason the camp was being closed. She explained that the Mountain was being shut down not because it was on private property but rather because it had become a public health nuisance and was noncompliant with the litter abatement code. The City sent a letter to the out-of-state owner in early April allowing him 10 days to clean up. To date, no response has been received or action taken. As a result, the City of Fort Worth and taxpayers will undertake the cost of demolition and cleanup.

A return trip to the Mountain a few days later found it to be almost a ghost town. Tonka and Chris were leaving. Bruce, Michelle, and Magik Mama were headed to the 7-Eleven at Beach and Lancaster. Sherry and her husband said they will stay until they are forced to abandon the ground they have called home for four months.

“Most of the residents will take back to the streets, most likely ending up in an old camp, thus starting the cycle all over again,” Red said. “I refer to this, rather cynically, as the Great and Never-Ending Lancaster Exodus.”

East siders sure as hell do not want to see more homeless drifting through our neighborhoods. I’ve personally fought for over a year to get squatters removed from our neighborhood along with the prostitution, drugs, and violence which these people encouraged. They had better stay far away from the corner of Beach and Lancaster. They won’t be made to feel welcome.

Some of the homeless people don’t have an identity to have a life if you’re so high and mighty why don’t you offer them work before placing your nose in the air some of you people who have been blessed with a home and food on the table fail to realize those things are blessings and take them for granted while judging your fellow humans but you will be judged when the time comes will you be let into the kingdom of heaven or forever sent to hell for the way your judging others money and a silver spoon don’t make you any better