A princess could have lived in the bedroom Sandy Storm had as a little girl. There was a pink canopy bed, a lacy, pink bedspread with matching pillows, and a big dollhouse filled with perfectly posed Barbies. Her room was a picture of childhood innocence and comfort, a stark contrast to a dark, terrible secret she kept hidden.

Storm’s mom had a wealthy live-in boyfriend, a banking vice president who belonged to a yacht club and a country club where he socialized with politicians and prominent businessmen who wore expensive suits. A shiny new Cadillac was parked in the family’s driveway, and one of the highest rated junior high schools in Texas was just down the street from their upscale, suburban home in Corpus Christi.

Their lives were elevated far beyond what they had in their tiny hometown in Southeast Ohio, where opportunities were few and poverty trickled down in a slow, agonizing stream, generation after generation. When Storm was 5 years old, her father committed suicide and she moved into her grandfather’s house with her mother. Seven people crowded his 1,000-square-foot space, including her mom’s siblings, who were also out of work and out of viable opportunities to escape that town. Her grandfather supported them all with a job he held at a local factory.

“There’s cycles of families on government assistance that have never worked,” Storm told me recently. “The grandparents and the parents and the kids all get some sort of government check. In the town I’m from, there’s a lot of that mentality, a lot of that cycle of poverty.”

She would reflect, years later, that life back then was difficult, but “at least we were safe.”

Their lives changed the day Storm’s mom met her supposed Prince Charming. He wooed and wined and dined her and offered her a glimpse of a life that seemed like a fairytale come true.

“He told my mom, ‘I can take you away from all this,’ ” Stormº explained.

They followed him from Ohio to Corpus Christi, leaving a life of poverty – and their family support system – more than 1,300 miles behind. But as one nightmare ended, another began. Prince Charming turned Storm into a child sex trafficking victim. She was just 6 years old, a kindergarten student, when it began.

Behind the men’s locker room of one of the fancy country clubs in Corpus Christi was another room, where Storm and other little girls were allegedly sold for sex to some of the most prominent men in the community.

“I don’t know who they were,” Storm told me. “I was just a little girl.”

Storm, now in her 40s, enjoys life as a Fort Worth wife, author, and human sex trafficking activist. She works with other activists and police departments and tells her story to help lawmakers, police, churches, and others understand the harrowing world of child sex trafficking.

Although it’s difficult to fathom that a family member would traffic a sister, a step-child, or a daughter, investigators with the Fort Worth Police Department said they have seen it multiple times.

By definition, sex trafficking happens when force, fraud, or coercion is used in the exchange of money for a sex act. When a juvenile under age 18 is involved, the crime of prostitution automatically becomes sex trafficking, even if there is no force, fraud, or coercion. That’s because an underage person cannot consent to the exchange.

The “force” is more subtle and comes in the form of the manipulation traffickers use to get children to do unspeakable things. Police and dozens of other local, state, and federal agencies in North Central Texas are working to arrest perpetrators, educate people about the causes of sex trafficking, offer possible solutions, and find aftercare for victims.

In Fort Worth and Tarrant County, the crime has landed squarely on the doorsteps of our schools, often hiding in plain view.

“Any child, any teenager, is at risk,” Storm said. “The schools in DFW are like stocked fishing ponds for traffickers. It’s a very easy job for them.”

Fort Worth police detective Andrew Matthews, who investigates child sex trafficking crimes, backs up Storm’s statement with what he has seen through his work.

“They’re impacting the schools because they’re targeting the students,” the detective told me during an interview, referring specifically to traffickers who target school-aged kids.

A study released this month by Thorn, an advocacy group, showed that most trafficking victims enter what the organization calls “the life” while they’re still in school.

Researchers at the University of Texas at Austin estimated in 2017 that there are 79,000 victims of child sex trafficking in Texas. Fort Worth police investigated 62 human trafficking cases in 2018 and 60 in 2017, up from 27 in 2016, according to figures provided by the department. The creation of the Tarrant County 5-Stones Taskforce in 2016, which is an extension of the department, is one reason for the increase, police said.

*****

Eastern Hills High School is one of the places in the Fort Worth school district that has helped young women who are being trafficked.

“As a department, we’ve dealt with several instances over the years where girls and guys have been targeted for sex trafficking,” said A. J. Hicks, the lead counselor at Eastern Hills.

In one of the cases, a student was ensnared in a sex trafficking ring that operated at an apartment complex outside the city limits of Fort Worth.

“There were young ladies that we knew of, who were going to school here, who were being coerced into sex trafficking in the evenings and on the weekends,” Hicks said.

One of the students was plunged into trafficking after she went to a party at the complex a couple of times with a friend. Once she was acclimated to the setting, the friend asked her if she’d like to make some money at the parties.

“And what she thought would be a one-time situation turned into a longer-term situation,” Hicks explained. “It went from her getting a little bit of money to ‘Well, we’ll give you part of it’ to … ‘Now you’re not getting any of it, but you have to keep doing it.’ ”

The student helped by the school was willing to file a police report, but that doesn’t always happen.

“What we’ve also found is sometimes we’re not as successful, and there are times when we are not able to get the students to want to leave the situation they’re in,” Hicks said.

Trafficking cases are not always obvious. They sometimes hide under other situations and symptoms like drug and alcohol abuse.

“A lot of times, they’re kept under control by … drugs and alcohol,” Hicks said, “so sometimes we might be working with a student knowing that they might need treatment for one of those things, and, come to find out, the place where they’re getting these substances are from people who are trying to get them to exchange ‘services’ of some type.”

Other signs are more overt, like the brands that some of the traffickers tattoo on their victims. That can include a trafficker’s name or a symbol such as Playboy bunny ears or dollar signs. One of the students in trafficking at Eastern Hills High had a dollar sign tattoo, Hicks said. A student might also appear extremely tired, fall asleep in class, or arrive at school with expensive things she didn’t have before, like designer handbags and clothes or a new iPhone. A teenager might mention having a job but will be evasive about where she’s working.

“So it is a problem,” Hicks said. “We don’t see it every day, of course, and I don’t believe the East Side is overrun with trafficking, but we do know that it exists. We’ve been trained by our district, and we also have opportunities to go to outside training about trafficking, to try to find out how to best serve our students and keep them safe.”

The trafficking advocacy group Unbound recently held a training for counselors and intervention specialists in Fort Worth schools. Other training sessions for staffers and students have been held at William James Middle School, which is located in an area of Fort Worth where police broke up one of the most violent and notorious child sex trafficking operations in 2016. The ring included several members of the so-called Polywood Crips street gang. Some of them were sentenced to lengthy federal prison terms.

“When kids walk out of William James, they walk into one of the most socio-economically depressed zip codes in Tarrant County,” said Fort Worth School Board President Tobi Jackson during a recent task force meeting at the Nashville Avenue police station, just a short distance from the middle school. “So, do you think they’re targets for traffickers? They certainly are.

“The thing that scares me about trafficking is it places our kids in slow-motion homicide while they’re with those captors,” Jackson continued. “When they leave their captors, they have higher instance of suicide. And that doesn’t matter if they’re 11 years old or 50 years old.”

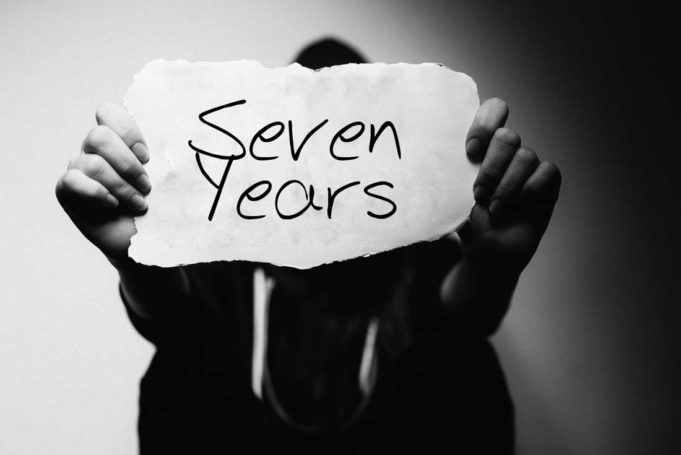

And Jackson is right. According to advocacy groups, a victim is expected to live only seven years after entering trafficking.

Hicks, the counselor, said she does not consider herself an expert, but from what she has seen, students are sometimes lulled into trafficking before they fully realize what they’re doing.

“Most people would not wake up in the morning at age 16 or 17 and say, ‘Hey, I want to get involved in this,’ ” she said. “It begins very subtly. A lot of deception is involved, and before you know it, you’re in over your head.”

School staffers follow the same procedures for reporting trafficking as they do for any student suspected of being an abuse victim.

“We follow the same policies for any student we believe might be in danger of abuse, by reporting it to the authorities, and we also talk to parents and get them involved,” she said.

*****

While Storm was being trafficked by her mother’s boyfriend in Corpus Christi, she was convinced by him to lure her elementary school classmates back home so he could turn them into trafficking victims.

“When I was being trafficked, it started at age 6, so I was in kindergarten, and [it lasted] until I was in seventh grade, and [for] the sex ring I was involved in when I was a child, I was a recruiter. … As a child, recruiting from schools was really easy. I would go to school, and I would bring girls home with me.”

Storm would ask them to play Barbies. “And [the girls] would get to my house, and we would be playing Barbies or whatever, and sometimes I would bring out the porn, or sometimes he would.”

They used photos and videos to train the other girls on what to do, telling them, “I’m going to show you a movie, and then I want you to do what you saw in the movie,” Storm said.

Other times, Storm was trafficked at parties at fancy waterfront homes in Corpus Christi or was whisked away in a Jeep to a private ranch near Freer, Texas, “in the middle of nowhere,” she said, where men preyed on children.

None of the abuse ever happened inside her bedroom, Storm said, but through the curtains of her window, she’d watch with a sense of dread as adults arrived for weekend parties. During one event, she recalled, the adults came in wearing Roman “toga” wear –– long, white flowing robes with gold-leaf halos around their heads. Storm said she knew from the movies she was shown that the adults were wearing nothing under those robes. And she said she was brought in to participate in their sex party in the living room.

The house was lit with candles, and all of it had an evil undercurrent, she said, even though the standard occult symbolism was not apparent. Storm, a Christian, adds these details because she believes the adults were devil worshipers.

“As I’ve read things and through my own healing, I believe it was Satanic ritual abuse,” she said. “There was not a star on the floor, but orgy scenes and sex with children is Satanic. The people coming to the parties were not just swingers. It’s not what it was about.”

How can any of this happen? For starters, traffickers are very adept at psychological manipulation and deception, police investigators said. There is no set “profile” of either a victim or a trafficker. Many of the people trafficking underage women are men, but some are women. Drug and alcohol addictions create an added layer of control to keep the girls in a barely conscious state as they are raped over and over by dozens of men a day. Other victims believe that the trafficker who is coercing them into sell selling their body actually loves them or is their boyfriend.

Trafficking is one of the fastest-growing crimes because it’s so lucrative. Drugs and weapons represent a one-time sale, but traffickers can sell a person’s body repeatedly for profit. Internationally, sex trafficking brings in as much as $99 billion a year, according to an estimate by Human Rights First, a national independent advocacy and action organization.

The demand is high.

“The issue is the demand,” Storm said. “We have an entire generation of men and boys who think that consuming another human being, trading that person’s soul for a moment of pleasure, is acceptable. That’s the issue.”

Another illustration of the problem is the most popular search terms published every year by sites like Pornhub.com, she said. Some of the top searches are for teenagers, cheerleaders, and other descriptions of underage females. The porn sites populate video after video, fueling addictions and implanting images of violence against women, as well, Storm said.

Anyone with a cell phone or a computer – at any age – can access the materials, she added.

But who are the people in the images that flash across someone’s computer or cellphone screen? Sex trafficking victims can come from all socio-economic backgrounds, although poverty is a common risk factor. They see trafficking as a gateway to a better life, and once they’re in it, they feel trapped, advocates and police told me.

Storm said the lack of a loving father in her life created a vulnerability that traffickers were able to use to exploit her.

“So if you’ve got daddy issues, and you’re seeking approval from an older man, and you’re getting all of this attention from men … that’s your identity,” Storm said.

People need to understand the risk factors, what causes vulnerability, Storm said. “And for me, one of those things was poverty,” she said.

Trafficking victims often come “from a broken home and are not able to just enjoy life,” Matthews the detective said. “They’re worried about, ‘Am I going to be able to eat today?’ ‘Am I going to be able to wear decent clothes to school?’ Some allowed themselves to be trafficked because they needed some clothes for school, or ‘I was hungry,’ ” Matthews said. “It breaks my heart.”

Fort Worth police have investigated trafficking cases with staggering levels of abuse and neglect at the hands of family members. One example is a 14-year-old from Louisiana who came to Fort Worth with a history of rejection, abuse, and moving in and out of foster homes. Many trafficking victims have been in foster care or the juvenile justice system at some point, according to Thorn, the advocacy group.

The teenager from Louisiana had a mom who refused to let her eat and wouldn’t buy her clothes for school and other necessities. Both the mother and her spouse had good jobs and could have well afforded to provide such things, Matthews explained.

“She’s molested by an uncle, she’s told by her family that they don’t want her, and she has her own sister traffic her,” the detective explained.

The sister was into prostitution, Matthews said, and she slowly groomed the younger girl before teaching her how to take provocative pictures and post them online. Next, the sister made her an account on Backpage, a website where sex ads were posted before federal law enforcement shut it down.

The younger sister was trafficked during summer months in Louisiana before she moved to Fort Worth a little over a year ago, Matthews said. When her mother found out her daughter was being trafficked, the detective continued, her only concern was scoring part of the money. One time, the mom intercepted a phone call and asked one of the traffickers how she could get involved.

“The mom got on the phone and asked, “What do I need to do for some money?’ ” Matthews said. She also asked her daughter for “some money … [to] pay the light bill.”

Instead of helping her daughter, the mom told her that trafficking was how she could help “pay her way,” Matthews said. The daughter, now about age 16, tried to land a regular part-time job, but she had no transportation and was not going to receive any transportation help from her mother. In desperation, the girl turned to trafficking because she lacked virtually all of the basics required for daily living.

“She was doing what she could to survive,” Matthews said.

Eventually, the stress caused her to break down at the Fort Worth high school she attended, and she set some papers on fire in a chemistry lab. An officer at the school sensed there was something deeper going on, so be began talking to the girl and eventually was able to ask some questions and find out what was going on, Matthews said.

The teen was removed from the mother’s home and placed in the care of Child Protective Services. Victim aftercare, as it’s called, is not always 100 percent successful. And in this case, it wasn’t.

The juvenile was placed in a Houston program for sexually abused girls, where all of the basics – food, a bed, a roof over your head – are provided. But she needed intense therapy, and the situation soon spiraled out of control. She was alone and went from “going 100 miles per hour to survive,” Matthews said, to being confined and staring at four blank walls. She had little to do but reflect on everything that had happened and what her life would turn into without any real family, Matthews said.

Early on, the teen got into a verbal argument with a counselor at the facility who claimed the teen had hit her, but when a judge ordered surveillance video of what happened, it showed the counselor was lying, Matthews said.

Once again, the teen felt betrayed. She ran away from the center. No one knows where she went, and police aren’t sure if she has returned to trafficking.

“The system failed her,” Matthews said.

*****

As foreign as it may seem, girls who are trafficked begin to think that the lifestyle is normal. Some of the trafficking victims with whom Matthews has worked told him they were coerced into performing sex acts “just to get a McDonald’s Happy Meal or earn a decent place to sleep,” he said.

One of them slept on a towel on the floor while her trafficker slept in a nice bed.

She said on bad nights, he’d even kick her out of the house, and she’d have to sleep on the steps, the detective explained.

“If they don’t make the money they need, or they don’t do what [the traffickers] want them to do, then they punish them,” he said. “There’s a variety of ways they punish them.”

Many of the teen trafficking victims the Fort Worth Police have seen are physically and psychologically abused. Volatile and violent behavior by the trafficker leaves them in a state of confusion, limbo, and dread. With no one else to turn to, they remain captive to their abusers.

“Who’s looking for them?” Matthews wondered out loud.

They have no one who knows or cares that they’re gone, he explained.

In other cases, “the girls were obviously beaten and hit around –– one of [the traffickers] held guns to their heads,” said Fort Worth police officer Hannah Rivard, who also works with trafficking victims. “Lots and lots of threats and verbal abuse with all of them. It doesn’t always look like the movies, where they’re tied up and can’t leave and so on. The girls sometimes appear to have some level of freedom, but it’s not real freedom, because they’re still held through psychological threats and coercion.”

One time, a trafficker ordered one of his victims to undress and get out of a car on a busy freeway.

“She was not completely naked, but most of her clothes were off,” Rivard explained. “And he dumped her on the side of the freeway and told her to just walk.”

By punishing and humiliating the victim, the trafficker is not just being cruel. He is crafting a “trauma bond,” a form of psychological abuse that chips away at the victim’s self-esteem and makes her emotionally dependent on the trafficker. It’s similar to what happens with domestic violence victims, Rivard said.

“They feel very vulnerable to where they never know what’s going to happen next,” she said. “They’re in a state of extreme limbo. They’re like any domestic violence victim, but this has the added elements of prostitution and rape and gang rape and all of that. It’s a very complex trauma for these girls.

“Most of them believe at some level that the pimp is their boyfriend, and so they’re held by that love,” Rivard continued.

Sex trafficking is often called “modern day slavery,” and that was illustrated by a case involving seven underage girls whose trafficker kept them locked inside his home.

“He had the back door boarded up, all of the windows boarded up,” Matthews said. “At night, after they were all in the house, he’d push his bed in front of the front door and sleep there, so that nobody could leave the house without him knowing it.”

The trafficker treated the young women as if they were livestock. “Those were his girls, he owned them, and he was making money off of them,” Matthews said, referring to how the trafficker viewed them.

Asked if they could leave on their own, Matthews recounted, “They said, ‘Oh, no. We can’t go outside from the back door.’ The way they explained it, it was normal to them.”

The girls believed their trafficker was locking them in the house to protect them.

Their trafficker acted as if he was doing nothing wrong because he believed they were literally his property, Matthews said. He ended up being arrested after “he spilled the beans on his whole operation” during questioning.

As sex trafficking cases continue to rise in Fort Worth, a natural question becomes “Why here?” One reason is location. Fort Worth sits on what law enforcement calls a corridor of crime “on 35, going north and south, and I-20 going east and west,” Rivard explained, “so it’s very easy to move girls from other parts of the country, from other parts of the state, without really having to expend much effort.”

The location makes it easier for traffickers in Fort Worth to transport girls to Dallas, Houston, Killeen, and Shreveport, Louisiana — all popular spots, she said.

“A lot of the girls go down to Killeen to work because of the military base,” Rivard said. “They literally have military discounts available.”

The main thoroughfares also lead to many hotels and motels where trafficking takes place.

“The most common ones go along the interstates, and we’ve probably dealt with every Super 8 and Motel 6 in Fort Worth,” Rivard said.

Part of the demand is driven by a culture that jokes about pimps and “hos” and creates the illusion that it’s a glamorous or cool lifestyle. Popular music artists sing about trafficking, and pimps write books about it. Some of them are even sold online. A simple search turns up titles like Pimpology by “Pimpin’ Ken,” How To Be a Pimp, and So You Wanna Be a Pimp?

One of the traffickers arrested by Fort Worth police was advertising a pimp book on his public Instagram account, Rivard said.

Mainly, it’s the manipulation, the mind control and psychological abuse, that allows the traffickers to convince school-age girls to go along.

“We’ve had many victims tell us, ‘I don’t know how he made me do it. I ended up doing it just because I wanted to. I wanted to do it for him,’ ” Matthews said.

To illustrate how manipulative the traffickers can be, Matthews mentioned a case in which the pimp had girls he was trafficking defending him on social media after he was arrested.

“He had girls jumping on social media saying, ‘Hey, we need to get him out of jail. He’s been wrongly accused,’ ” Matthews said. “He even had people raising money for him.”

*****

Storm knows firsthand how skilled traffickers are at manipulating children and young women.

She said what she was involved in as a child was a “sex ring” because “it wasn’t just one perverted man that was doing this to children. Some of these girls, when I would go to their house to spend the night or something, their dads were doing the same things that were happening in my home, so there was a network of men.”

Storm was trafficked until she was 12 years old, when her life took yet another downturn. One of the classmates she brought home refused Storm’s trafficker when he “tried his normal moves” on her.

“She had a good mom and dad, and they taught her it was inappropriate for someone to touch you,” Storm said. “She went to the teacher the next day, and the teacher called the police.”

Her trafficker remained defiant even after his arrest, which ended up being reduced to a misdemeanor, Storm said. She recalls his saying that she and her mom would lose everything, and they did. They moved their belongings into the garage, but the roof leaked during a rainstorm and damaged whatever belongings they had managed to salvage. Storm’s beautiful bedroom set was sold, and she was told it was to help pay for the trafficker’s attorney’s fees.

“I felt like I was being punished,” she said.

Storm and her mother returned to their small Ohio town and also returned to a life of struggles and disappointments. Soon after, one of Storm’s classmates from school introduced her to an older friend, a man in his 30s.

“When I was 16, I was at our swimming pool, at our community swimming pool,” Storm explained, “and a boy I went to school with came up to me and asked me if I wanted to go get high. And he had a friend. And he pointed outside of the gate of the swimming pool and said, ‘There’s my friend. He’s got some weed. Do you want to go get high?’ Well, yeah. I wanted some free weed. I started getting high when I was 9 years old, because my trafficker would give me alcohol and drugs to make it easier to make porn of me or to make it easier to do the things he was wanting to do with him and his friends, and so I had been getting high almost every day.”

Storm said she turned to drugs to block out all of the pain in her life.

Her classmate’s “friend” was indeed a trafficker. Similar to the victims police described, Storm believed he was her boyfriend. She eventually gave in to his demands to bring over girls to his house to “party,” yet she was devastated when she found out he was having sex with one of her friends.

“I was so angry and hurt,” Storm said.

Looking back, she realizes he had no redeeming qualities.

“He wasn’t attractive,” she said. “He wasn’t witty. He wasn’t fun. He wasn’t funny. There was nothing that attracted him to us, except we had daddy issues, and he had drugs. And he was willing to give us drugs and give us the attention that we so desperately craved. I’m sure she and I weren’t the only ones. I’m sure there were lots of other girls that he was doing this to.”

Storm stayed in a Neverland of drug addiction and sex trafficking until 2004, when she finally broke out of that lifestyle for good. For Storm, the turning point was what she describes as “an encounter with Jesus Christ,” a profound sense of peace and, ultimately, healing and redemption. She is certain God was really there all along, protecting her. How else could she have survived? she asks. The healing from everything she experienced was nothing short of supernatural, she said.

She also went on to meet a wonderful husband who “pours so much love into me,” she said.

Part of Storm’s message is that trafficking is happening everywhere.

“It is happening in every neighborhood,” she said. “I guarantee you, because it happened to me in a suburban upper-class neighborhood in South Texas next to the top-rated school in town, and it happened to me as a child. It happened to me in Ohio in that poverty-ridden community. It happened to me as a young adult in the suburbs in apartments and going from one drug dealer’s house to another. And it happened to me in high-end hotels, and I was literally being prostituted. And it happened to me in the scuzziest hotels, crappy hotels, hotels where you pay by the hour. It’s happening everywhere. I’ve experienced trafficking in every socio-economic category and everywhere you could possibly be because there’s a demand.”

The stream of men willing to pay for sex was constant, she said.

“I never ran out of men that were willing to pay for my brokenness, for me being completely shattered,” Storm said.

I asked her that if she could say something to her traffickers, what would it be?

“I truly forgive them for what they did,” Storm said. “I’m not making light of what happened or what happens to the millions of victims every day of trafficking, but [the traffickers] are part of a broken society that gave them the opportunity to do that to me without consequence, so I can see that that was not the life that was intended for either of them. But I can also see that they were just a part of the issue. They were just a blip on the radar screen of the bigger picture. The issue is that they even had that opportunity.”

Hicks, the high school counselor, said one of the first steps to end the trafficking is to shine a light on the problem.

“I guess the biggest deal is that it’s allowed to flourish in the dark,” Hicks said. “As long as people don’t know, then [traffickers] can continue to do what they’re doing, but if a light is turned on, then that’s the first step. That’s all we can really hope for here, is to turn the light on when we see these kinds of things.”

Both of Storm’s traffickers – the one in Corpus Christi and the one in Ohio – have since died, she said, but some of the memories have not. She still thinks of the other trafficking victims and wonders what became of them. She can still see the face of a girl who was brought to that same backroom at the country club, where wealthy middle-aged men were allegedly waiting to exploit them. She was a beautiful Indonesian girl who was “so sad to be there,” Storm said.

Today, in Fort Worth and in the city’s surrounding communities, and in cities and towns across the nation, the cycle of trafficking continues for other young women.

“But it doesn’t have to be that way,” Storm said. “We don’t have to raise vulnerable kids that end up being trafficked. We don’t have to raise people who would be willing to pay to rent another person’s body.”

Through her work to raise awareness about the problem of sex trafficking, Storm filmed a video of herself driving around streets in Fort Worth and Dallas in areas where the crime abounds.

In one part of the video, a slender, young blonde woman walks along the side of the road of Harry Hines Boulevard in Dallas near Love Field Airport, where passengers board planes and soar high above the clouds on their way to pleasant destinations. Under a traffic bridge, two girls openly smoke a crack pipe and pass it back and forth. A prostitute walks through the midday sun in a parking lot of a nearby porn shop, looking for her next customer.

Storm sees these depressing scenes as only she can, through the eyes of someone who lived it.

“You have to have hope, or your heart will shatter,” Storm told me. “I got out of this and I know they can, too.

“I have so much hope.”l

Excellent article. I had now idea how pervasive a problem this truly was and is. These adults that are complicit in destroying these young lives should face severe punishment.Thank you for enlightening us again.