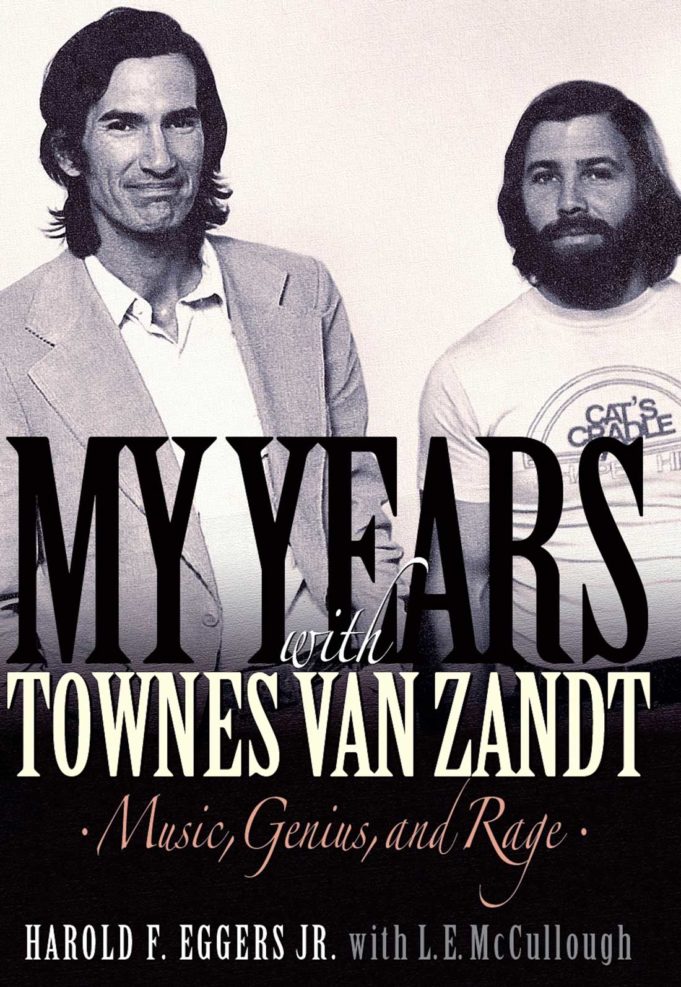

Harold Eggers didn’t set out to know Townes Van Zandt to the core, but that’s what happened after 20 years spent crisscrossing the country together in the cab of a pickup truck. Serving as road manager and driver, Eggers carted the gifted but self-defeating Texas singer-songwriter to gigs from 1976 until the singer’s death on Jan. 1, 1997. All these years later, Eggers is left with a wounded but overflowing heart and enough insight and stories to pack a book. My Years with Townes Van Zandt: Music, Genius, and Rage, written with L.E. McCullough, provides an illuminating, melancholic account of the artist who gave us “Pancho and Lefty” and other songs about hardscrabble characters, songs that were as beautifully written as a John Steinbeck novella.

Van Zandt, a Fort Worth native from a prominent family, saw most of his early memories erased after receiving a series of electroshock treatments at 19. His errant behavior had alarmed his parents and others –– people who didn’t understand why a seemingly intelligent young man would purposely fall backward out of a fourth-story window. Van Zandt treated what would eventually be diagnosed as bipolar disorder and depression by swilling vodka, interspersed with occasional visits to mental health facilities to dry out. By 1976, Van Zandt had established himself as a powerful wordsmith with little commercial success. No surprise that the youngsters didn’t really go for his deep lyrics about broken people in desolate places sung in a bluesy monotone. This was the era of bombast, Led Zeppelin, Ziggy Stardust, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and disco.

Outlaw Music made stars of other Texas songwriters such as Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, but Van Zandt toured in relative obscurity, even after Nelson and Merle Haggard topped the country chart with their cover of “Pancho and Lefty” in 1983.

Eggers, a young Vietnam veteran self-treating post-traumatic stress disorder with massive amounts of pot, made a perfectly imperfect fit with Van Zandt. When the young tour manager was being hired, his new boss told him, “I hear you smoke a lot of weed. I don’t smoke weed much at all. I prefer hooch. People give me weed for free all the time, so I will give it to you. One less expense for you.”

Over the years, Van Zandt’s demons and distrust of people provided a skeptical yin to Eggers’ more stable if stoned yang. Together they survived and occasionally thrived amid myriad tragicomic adventures. Their intimate relationship crossed “all personal boundaries,” as Eggers describes it. They worked, traveled, ate, slept, talked, and caroused for months on end. They shared a hotel room to save money – and so Eggers could keep closer watch on his unpredictable travel companion. Van Zandt drank vodka until falling asleep. Then Eggers would secretly pour vodka into a sink or toilet, leaving just enough booze in the bottle to supply his buddy’s badly needed morning pick-me-up but not enough to prompt a full-blown bender.

Van Zandt comes across as an asshole and mental wreck at times. That’s the way he wanted it. The singer knew Eggers would write a book about him one day, and Van Zandt made his friend promise to publish the brutal truth without any whitewashing. Eggers complied. Still, Van Zandt’s assholery is more than counter-balanced by Eggers’ many stories about his generosity of spirit, support for the oppressed, and — always — absolute authenticity. Van Zandt embodied a seeker on a lifelong quest to arrange precise words in ideal orders to make life-changing impacts on listeners. He battled demons or, more accurately, invited them inside his mind for long talks. He saw and spoke with spirits regularly, Eggers writes. Maybe that explains the otherworldly nature of Van Zandt’s lyrics that made his songs sound so different from other folkies.

Eggers compares his dangerous stint in Vietnam to his years spent touring with a mad man. Van Zandt lived in a “perpetual war zone that reflected the unceasing turmoil in his mind and heart,” Eggers writes. When the two first partnered up, the artist had played his share of rough dives and could maneuver deftly among tough crowds. Eggers was still learning. An ill-advised wisecrack prompted a “large, loud-voiced woman” to knock Eggers unconscious with one punch during that first tour. Eggers learned to keep his eyes open and mouth shut, although Van Zandt’s pranks and insults to the public would put them at risk of violence or arrest often enough.

“Cheer up, it’s only going to get worse” was Van Zandt’s typical reply whenever Eggers attempted to ward off impending doom.

The tall but frail Van Zandt’s tendency to piss off people prompted Eggers to suggest carrying a pistol for protection. Van Zandt refused, saying, “You’d be shooting people left and right and, on the wrong night, that could include me.” Instead, Van Zandt relied on an old trick to disarm potential threats – he’d threaten to slit people’s throats and drink their blood.

The contradictory Van Zandt yearned for more musical appreciation from critics and the public even as he derailed efforts to make it happen. His fans were few in number but rabid in devotion, and the singer touched them best from the stages of small, intimate clubs. When booked into large venues with higher expectations, Van Zandt (perhaps subconsciously, maybe by design) under-performed at times. Self-sabotage ran deep in his psyche. Early in the book, his escapades reflect a sense of hell-raising rebellion. By the end, they’re more desperate and sad.

Sorrow drenches every page as Eggers describes an aged and weary Van Zandt, moving about in a wheelchair, blowing a high-paying record deal by insulting the financier’s wife, and then ruining his last recording session by endlessly testing the patience of everyone involved. Eggers’ descriptions make the reader want to reach into the book to simultaneously hug and slap sense into the tormented troubadour. Hugs and slaps wouldn’t have mattered. Friends and fellow artists tried those approaches and more with little success. Eventually, they chose to accept and embrace the complicated man as he was. Readers of this well-written love letter will probably do the same.

My Years with Townes Van

Zandt: Music, Genius, and Rage, by Harold Eggers

Backbeat Books

228 pps.

$29.99