Jason Hernandez knows what it’s like to feel hopeless. A drug dealer starting at age 15 from McKinney, he was rounded up with several other local drug dealers in a 1998 raid, shortly after he turned 21. He was charged with conspiracy to distribute crack cocaine and methamphetamine, among other things, and offered an eight-year sentence if he would testify against another dealer. He wouldn’t, went to trial, and was given a sentence of life-without-parole plus 320 years.

It was Hernandez’ first offense, and no drugs were found. “It was a dry conspiracy” is how he described it to me several years ago when I first interviewed him for the Weekly (“Not Another Brick in the Wall,” Nov. 11, 2015)

Hernandez was sentenced at the height of the war on drugs, and he was one of hundreds of first-time nonviolent drug offenders sentenced to life without parole in that era. Life without parole is really a death sentence, because you will never see the world outside of prison walls again. Hernandez was hopeless.

Inside the federal penitentiary system, he learned to weld and spent countless hours poring over lawbooks, writing his own clemency petition, and contacting people and organizations on the outside, looking for a glimmer of hope. Encouragement arrived when someone he knew put him in touch with the American Civil Liberties Union, which featured Hernandez’ story in the 2013 report A Living Death — Life without Parole for Nonviolent Offenses. By that time, in 2011, Hernandez had already submitted his clemency petition to the federal pardon attorney’s office at the U.S. Department of Justice.

“I didn’t know if it would get serious consideration, so I also sent a letter to President Obama,” Hernandez told me over coffee recently. “And he actually read it.”

The letter was included in the 2018 Random House book To Obama, with Love, Joy, Anger, and Hope.

“And 26 months later,” Hernandez said, “I was granted clemency.”

He served a year in a halfway house and was finally released in August 2015. Hernandez knows he was incredibly lucky to be afforded presidential clemency, but he also knows he was incredibly lucky to have a place to land. His folks were still alive, and he moved back in with them. He scored two jobs and slowly reintegrated.

“But then something funny happened,” he told me. “Stories like the one you wrote were seen by prisoners or friends of prisoners, and people started to get in touch with me. Then organizations began to get in touch. They all wanted to see the letter I wrote to the president and my clemency petition, because it was evidently well done. That was funny because I never went to law school or anything.”

Rather than shy away from the requests, Hernandez jumped into the fray. Because he was still on supervised release — he had eight years of that if he survived the life-plus-320 — he could not be in direct contact with prisoners. He could, however, be in touch with their advocates: “I would go over prisoners’ petitions and fix them and tell people how to start getting grassroots support for their clemency, and I actually helped six people get clemency through President Obama.”

One of those people is Josephine Ledesma, who was given life without parole for conspiracy to transport drugs — despite her having no drugs and being a first-time offender. She served 24 years in the federal prison system before she was granted clemency in 2016.

“I have never met Jason Hernandez, but I love him,” said Ledesma, who now lives in El Paso.

Before she got in touch with Hernandez through a friend, Ledesma had applied to clemency organizations without luck and had even written her own clemency petition.

“I didn’t know if it would work,” she said, “because I didn’t have a lawyer to help me, but then someone got in touch with Jason, and he took my petition, which is really a packet of information, and put it in a great format and submitted it for me. And then he talked about me everywhere he went, even to the White House, and he made a big copy of a picture of me and showed it everywhere. He was a blessing.”

Like Hernandez, Ledesma was lucky when she was released. While inside, she said she worked at a call center and used her pay to call her children almost every day of the 24 years, which kept their relationship strong. When she was released, she moved into a small house behind her daughter’s home. Her oldest son bought her a car, and then she landed a job.

Ledesma, who recently turned 60, supports herself and is enjoying her life.

“Even when traffic is bad,” she said, “it doesn’t bother me. I enjoy that too. I am just so happy to be out, to be talking with you on the phone from out of prison, and Jason is really the one that made that happen.”

Since those first entreaties for help with clemency petitions started to come, Hernandez has not slowed down.

“Clemency is a power that the president and all 50 governors have, and it’s rarely used, and I think that is wrong,” he said, “so colleges would bring me in to talk about clemency, and other organizations brought me in, and I’d talk about how to do a successful clemency petition, how to do a grassroots campaign, and so forth.”

He couldn’t keep up with the demand for help on individual petitions, so he decided to put his information into a manual that could be circulated in prisons, sent to universities with criminal justice programs, and placed anywhere else people who work with prisoners might have access to it.

“I just wanted to make that curriculum available,” he said.

Last year, he applied for and received a fellowship from George Soros’ Open Society — a program that sponsors individuals working to make fundamental changes in society. It was an 18-month grant that allowed Hernandez to take leave of his day jobs and focus on the clemency project. He’s working with a law professor and two students at New York University on formatting his information and also working with a law professor at Texas A&M in Fort Worth on preparing actual clemency petitions for people.

One of the people for whom a petition has been prepared is Crystal Muños, who is serving 20 years for conspiracy to distribute marijuana. Another, whose petition will be prepared this spring, is Elisa Castillo, who is serving life without parole for conspiracy to distribute marijuana and cocaine.

“Both first-time offenders, no violence involved in the conspiracies,” Hernandez said. “I think there was some product in both cases, but most of the dope involved in the conspiracies was ‘ghost dope’ that nobody ever saw.”

Amber Baylor, a former federal prosecutor who joined A&M last fall, said she was hired to start a criminal defense clinic at the law school: “I wanted to make sure the clinic was an opportunity for the students to practice under supervision and to provide services to folks who cannot afford an attorney, so the clinic focuses on indigent defense.”

Baylor said that when she moved to Texas from New York City, she began to get in touch with people who were doing grassroots justice work here and that one of the people she was recommended to talk with was Jason Hernandez.

“We met, and Jason spoke with my students about his story and the work he’s done since he got out,” Baylor said. “They loved the idea of working to help people get clemency.”

A few months ago, Baylor and Hernandez decided to take up the clemency cause of Muñoz.

“The students did their work while Jason provided guidance,” Baylor said. “He’s very realistic about what the audiences who are going to be considering the petitions expect.”

The clemency petition was submitted to President Trump’s pardon attorney’s office by Muñoz’ advocate, Amy Povah, founder of Can-Do Clemency, a nonprofit working for clemency for all nonviolent drug offenders. Povah herself was a clemency recipient under the Clinton administration, after serving nine years of a 24-year sentence for conspiracy in an MDMA (ecstasy) case.

Baylor said they have not yet heard back from Povah on the petition but added that it was recently submitted and is not surprised. During this spring semester, Baylor’s students will work with Hernandez on a clemency petition for Castillo.

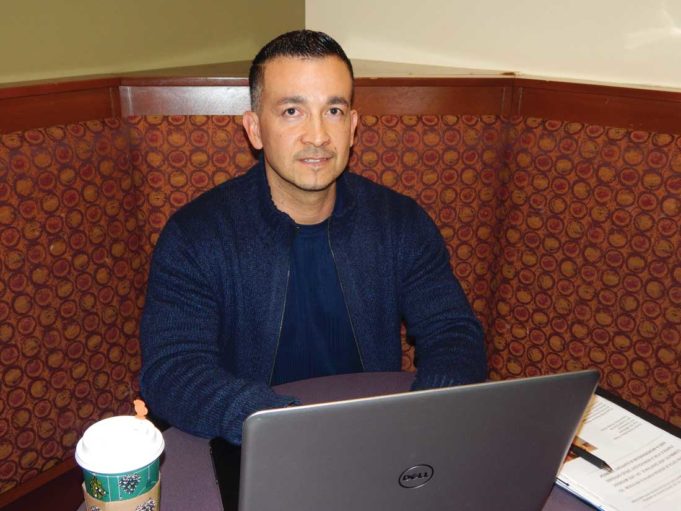

Hernandez, 41, is sharply dressed and good-looking, with closely cropped dark hair just beginning to gray at the temples. His eyes are clear, his smile bright, and his handshake warm.

“There are just too many people doing impossibly long sentences for nonviolent drug crimes,” he said. “They need someone working on their behalf to get them a second chance.”

While he acknowledges that he concentrates on nonviolent first-time drug offenders serving 20 years to life without parole, Hernandez doesn’t think they should be the only class of offender receiving help to have their sentences reduced.

“I can only concentrate on one group of people who are suffering from these long sentences, but other groups need advocates, too,” he said. “That’s why I would like my book, this curriculum, to go out not just to jails but to colleges, universities, and prisoner advocacy groups as well. Not many lawyers are going to spend the time to learn how to prepare an advocacy plea for someone who is in prison with no money, but this will provide that information for them so that they don’t have to learn from the beginning.

“Here’s the thing: If the president and all 50 governors had people who were scrutinizing who is in their jails who maybe deserve another chance, things would begin to get better for a lot of people.”

Very Blessed Yu are. my husband has been incarated for 17 yeas for a WRONGFUL CONVICTION PLEASE GOD LET HIM COME HOME AME