Every year, a few bands drop recordings just after the cutoff date to be considered for our annual Fort Worth Weekly Music Awards. Recent releases from Clint Niosi and Slow Draw will no doubt garner attention in next year’s awards, but I’m writing this if for no other reason than I don’t want our local music cognoscenti to forget them. In terms of ideas, both of these albums have a lot going on, creating concrete mental visuals out of sonic moods.

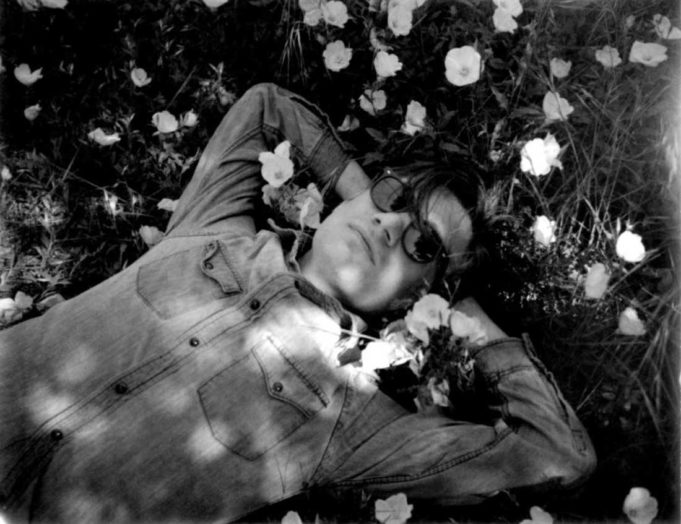

Clint Niosi’s music has a cinematic feel to it, even when it’s less abstract and ambient (as his actual film scores tend to be). Even his musical projects that are composed of traditional verse-chorus-verse-type arrangements sound as if they were made for a film. Perhaps unsurprisingly, his new album is called Daedalum, which is also the name of an archaic device used to view animation, more commonly known as a zoetrope. A zoetrope is a cylinder with a succession of differentiated pictures illustrating a subject in motion printed on its inner surface, and when spun, it allows the viewer to perceive movement through the vertical slits cut in the cylinder’s sides that bracket each frame. Like the mechanics of all animation techniques, a daedalum tricks the brain into believing separate, static images are a single moving subject, but since its effect is basically like watching a horse run by peering through the gaps in a fence, the experience feels incomplete and leaves you with a peculiar, unsettling longing.

The daedalum/zoetrope idea is reminiscent of that famously paraphrased line in 1 Corinthians 13:12: “For now we see through a glass, darkly, but then face to face.” Both sonically and lyrically, Niosi’s new songs seem to be looking at life in a similar fashion, glimpsing the winding paths of the past, present, and future through the darkened lens of cynicism. The eight songs, mostly minor key blues progressions given a jazzy shake by drummer Eddie Dunlop’s percussion, convey ideas about the uncertainty of life (“Fortune”), ebbing hope (“Not Even”), and the inexorable steps of time (“September”). Niosi’s baritone sung over his own reverberating guitar builds the songs out of shadows, further shaded by the lush groan and murmur of wife Claire Hecko’s viola. Dunlop, along with Joe Rogers’ keyboard melodies, make the music jump enough to keep it out of the realm of dirges, and the cumulative effect is like a soundtrack to a film noir written and directed by Nick Cave and starring Jarvis Cocker.

Mark Kitchens’ Slow Draw is a side project (his main gig is playing drums in the stoner-jazz duo Stone Machine Electric) that, like Clint Niosi’s music, sounds like it could be made for the movies. Last November, Kitchens released Slow Draw’s debut, a five-song EP of ambient, experimental, drum-and-synth explorations. Avoiding It’s creepy synthesizer doodles, electronic drone, and firecracker pops of live percussion created an aural mood not unlike the ones you’d find in the early films of David Cronenberg or John Carpenter but wilder-sounding, like the machines had come alive and were rapidly losing all rational thought processes.

Recently, Kitchens followed up his first Slow Draw recording with a new one, and while it comes from the same place – meditative tempos and ominous moods drawn in synthesizer swirls and ghostly electronic hums – it’s dramatically different. Light Is the Path (and available on CD and cassette, unlike the digital-only Avoiding It) seems to be the score for a different imaginary movie, though one that might exist in the same universe. In this case, melancholy guitar and keyboard chords float over Kitchens’ beeps and loops, and snatches of plaintive melodies that nod in and out suggest barren landscapes, bleak and chilling, cast in day-for-night lighting that’s disorienting and unsettling but hard to steer away from.