For about a year, my wife had been telling me the same thing that my 6-year-old son said to me in the car the other day (at least a non-threatening version of it). Now’s probably not a good time to bring up all of the demonstrably false accusations of tuning her out that said wife has leveled against me since our courtship began 20 wonderful, joyous, 100-percent pain-free years ago.

“What are you talking about, Apollo?” I replied, decelerating back into the right lane.

“You get angry a lot,” my son said before repeating his initial question: “What’s wrong, Daddy?”

Ashamed, almost as if I were the child, I stretched my mouth to display a set of teeth tarnished by too much coffee and, up until three years ago, too many cigarettes. I pressed my face up against the rearview mirror.

“I’m not angry, zweet boy,” I mumbled, alternating my vision between my son’s reflection and the road. “Daddy’z happy. Zee? Zmiling Daddy.”

My son went back to looking out the window. I shrugged, relaxed my mouth, and went on, “It’s just that those big trucks back there were going really slow, and I didn’t want us to get hit by the cars going fast behind us. That’s all.”

“This is you,” Apollo said, and he issued a long, low growl: grrrrrrrrrr.

“That is you, Anth,” Dana said from the passenger seat, her eyes fixed straight ahead. “I tell you that all the time.”

I would argue that I’ve always been a little ornery, always been apt to revealing my “Yankee-Pittsburgh-jerk” side, as my wife says, referring to the lovely Rust Belt city where I was born and raised and where conversations are conducted with as few niceties as possible. Still, I suppose the argument could be made that I’m touchier than usual now. My recurring nightmares about Donald Trump aren’t the only reasons. (Someone, please, put that clown in jail by now.) I just turned 47. That places me on the downside of middle age, where the roller coaster ride has gone from cresting hopefully to plummeting unceremoniously, rapidly into the abyss. And this is a development that has continued eluding my higher reasoning functions. All I can muster is a feeble “Middle age sucks. Highly not recommended.” We middle-agers routinely wake up with random bruises on our bodies, and we are continually haunted by the thought that, well, this is about as good as it gets with our jobs, our bodies, and sex. We constantly worry about our kids and the material possessions that constitute our domestic lives – why is my car shrieking? what is that murky pool of liquid beneath the sink? shouldn’t the AC have kicked on by now? – and we are forever beating back reality, emotionally and physically wrenching reality. We might not be totally gray and pudgy and may even kinda sorta resemble our 25-year-old selves, but we can no longer do what we could as few as five or 10 years ago. There’s absolutely nothing redeeming about this dark stage of life other than maybe being able to eat dessert before dinner without getting in trouble. Of course, I might be a little bitter. I’m a human being.

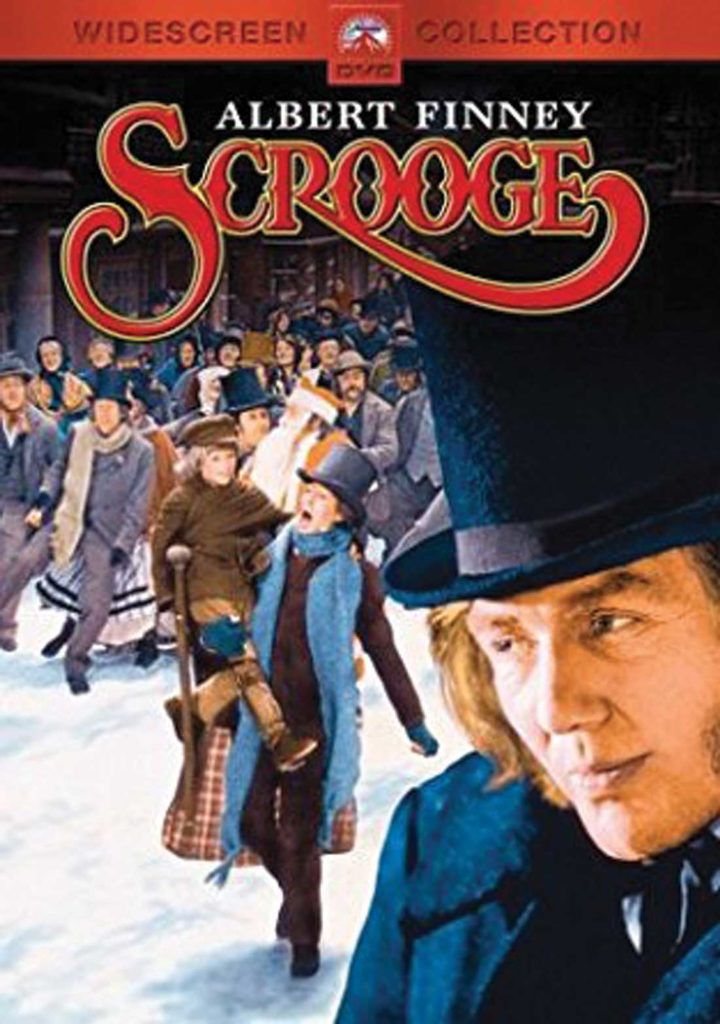

Dana and I are big on mottos. Our refrigerator is covered with printouts of inspirational sayings. “The mind is everything. What you think, you become;” “Life is 10 percent what happens to us and 90 percent how we react to it;” “Challenges are what make life interesting, and overcoming them is what makes life meaningful.” Go ahead. Laugh it up. I don’t blame you for scoffing at two adults simply trying to be nice to each other and their kid. Just remember that being nice is always better than the foaming-at-the-mouth, potentially bloody alternative. (“Being not dead and avoiding hurting people: highly recommended.”) Dana and I have even tried our hand at our own sayings. Last year, she came up with a new one: “Buddy, Bob, Boo.” It’s what we say to one another when one of us starts whining or staring off into space with a dazed, defeated look on his face. Most of the exchanges are between my wife and me. Apollo is still a little too young to be able to manifest the concept of trying to be more like “Buddy,” the main character from the movie Elf who’s so deliriously upbeat he probably has brain damage; “Bob” Cratchit from Scrooge, the only version of the Dickens classic (including the source material) that matters; and “Boo,” a.k.a. Dana’s dad, Papa Boo, the retired Air Force colonel and fighter pilot who never complains (at least around us).

“Buddy, Bob, Boo,” as you, no doubt cringing, may imagine, was birthed around Christmastime. As recovering Catholics, Dana and I have always celebrated the holiday season in a hyper-traditional, old-school way: decorations, movies, and music. Lots of it and nonstop. The point is to exaggerate the joy because life is otherwise hard, cruel, and unforgiving. Japan keeps killing whales freely, surgical masks and tampons are washing up on Australian beaches, and as if living in the world’s largest refugee camp weren’t soul-destroying enough, the 700,000 Rohingya in Bangladesh are sitting in the path of an oncoming monsoon, just one more natural disaster in a string of natural disasters going back years that are the direct results of climate change. Why aren’t I spending our precious time talking about the Rohingya? Good question. Better answer. Not only am I a big, fat sissy la-la who can’t abandon his family to take a trip around the world to report on what’s happening there, I’m also a big, fat sissy la-la who can’t even point to Bangladesh on the map. I only recently taught myself where North Korea is –– for some morbid, possibly The Day After-inspired reason, I want to know where the civilization-ending nukes will be coming from. A spiked egg nog is totally cool at 11:30 a.m. on weekends in O Little Town of Marianiville. In the words of the Lizard King, “But I tell you this, man. I tell you this. I don’t know what’s gonna happen, man, but I wanna have my kicks before the whole shithouse goes up in flames. Alright? Alright!”

Nostalgia is another driving factor. Your holidays may have sucked as a kid, but Dana’s and mine, respectively, were glorious. And I say that with no real sense of shame or guilt. The joy I experienced, however contrived, however fleeting, served me well in my youth. It protected me from the collapse of my father’s business and his descent into alcoholism, for one thing. For another, it insulated me from the abject loneliness that trailed me the rest of the year. I want no less for my son now. In a break from tradition last winter, my family started watching Elf and Scrooge –– and It’s a Wonderful Life, Polar Express, and, when Apollo was asleep, A Christmas Story –– an entire week before we began decorating the house on Thanksgiving morning. (We decorate the house for Christmas every Thanksgiving morning.)

In another break from tradition –– that I haven’t been brave enough to share with Dana yet –– I’ve started listening to Christmas music in private.

Like constantly.

*****

Upon reaching middle age, or maybe even sooner, we may stop doing fun things for fun and begin doing them out of necessity. Like drinking. What once was thrilling and new – maybe sneaking a few I.C. Lights from the fridge with a couple of high-school chums to ameliorate another boring summer Saturday night –– is now as vital to existence as air, water, and Twitter. It’s that dopamine kick we crave, that little pick-me-up that can carry us through perhaps another hour or more of writing/editing or *groan* a full day of parenting. Don’t get me wrong. No one’s trying to relive Spring Break ’92 here. (The only jumping around we do is when we can’t see our son and hear a crash from another room.) Dana and I are just doing enough on the weekends and sometimes after work to “achieve cruising altitude,” as I say. That’s it. (As The Onion put it: “Man Going To Take Edge Off With Decades-Long Slide Into Alcoholism.”) More so than as a worker bee, as a parent, no one can afford to sleep in past 6 (OK, 6-ish). Breakfasts must be made and children cleaned, dressed, and engaged. I can hear you from here: “Working out will give you a good dopamine rush, too. Have you tried that, my good sir and your gentle lady?” Yeah, bro, to answer your question, when we can, but we just can’t now. Our entire household feels like it’s under fire.

Our family is somewhat atypical. Dana (white) and I (sort of an ashy, jaundiced tan) adopted Apollo as a baby from Ghana, where he had been living, first, in an orphanage and, later, in foster care. Our sweet boy has some developmental delays and challenges from probable neglect in infancy and earlier – he had four hernias and a partially collapsed lung due to illness when we met him. Like most victims of neglect, he will always be that much closer to having his fight, flight, or freeze response triggered than “normal” people. Not just “normal” kids. He will be this way his whole life. As smart as he is – he’s reading on a 5th grade level – Apollo sometimes acts (more like “reacts”) a little younger. The phone calls from school started when he was in pre-K. They began innocently enough. “Apollo’s having a rough day,” his teachers would sing. And then, before Dana and I knew it, the normal family life that we had been enjoying was snatched from us. “We know you and your wife both work full-time,” his teachers now snarled, “but we need at least one of you to come pick up Apollo and take him home because we can’t handle him.”

Dana and I have done all we can, including stopping what we had been doing in the middle of the day several times to drive to his school, pick him up, and take him home to – what? – scrub the floors? Clean the windows? Wash the dishes? Because it never dawned on his pre-K teachers that maybe after the ninth or 10th time they called us, our son knew he was getting exactly what he wanted every time he acted out: to be sent home, glorious, home. (Capsule review: There are only so many chores you can assign your 3- or 4-year-old before you begin to feel like a horrible person.)

To his kindergarten’s credit, the teachers and administrators there have been much more active trying to “solve” Apollo themselves instead of relying on us. We still get phone calls, and since I’m the main contact, I instantly become nauseous every time my phone rings during the day. “Here we go,” I whine to myself as I pull the device from my back pocket to check the caller ID. (Oh, good. Just another Beto O’Rourke robocall.) The upshot is that my wife and I no longer feel like we’re being forced to parent our child from a distance. Are we ready to start working out then? I would say, “Maybe this summer,” but since Dana and I still both work full-time, Apollo is spending his days at the local YMCA. Apparently, they also have my phone number. They haven’t called yet, but I’ve been pulled aside already –– twice. Here we go.

You probably hate Christmas. Most people in my lefty ambit, if they acknowledge the holiday at all, do so only ironically: ugly sweaters, obnoxious tree ornaments, garish indoor light displays. My wife and I are not so quick to resort to the contagion of snark come the fall and winter. Though I don’t go to church or anything, I still pray. Sinking to my knees, clasping my hands together, and closing my eyes serves a dual purpose. It allows me to send a message to the universe that my son needs all the strength and guidance it can muster for him (I also pray for “everyone who’s homeless and hungry, and the Rohingya”), and praying also lets me express mindfulness, specifically gratitude. I am exceedingly grateful for my family –– and the roof over my head and my job and electricity and running water –– and I want to keep it that way. Being mindful is the first step. Being mindful year-round is something else entirely. Enter: “Buddy, Bob, Boo.” And, for me, Christmas music.

Here’s why Christmas music rules – to me (and perhaps to me alone). There’s the music itself. You can’t claim to love Music-with-a-capital-M or be capable of discerning Radiohead from Toby Keith and not like even a little Christmas music. I understand the emotional baggage. Not every childhood was as happy as my wife’s or mine. I also know that, as a holiday geared toward children and Christians, Christmas in all of its forms (decorations, music, movies, advertisements, sentiments) can annoy childless adults and non-Christians to the point of rage. However, I also know there’s more to Christmas music than “Santa Baby” or, good grief, “Grandma Got Run Over by a Reindeer.”

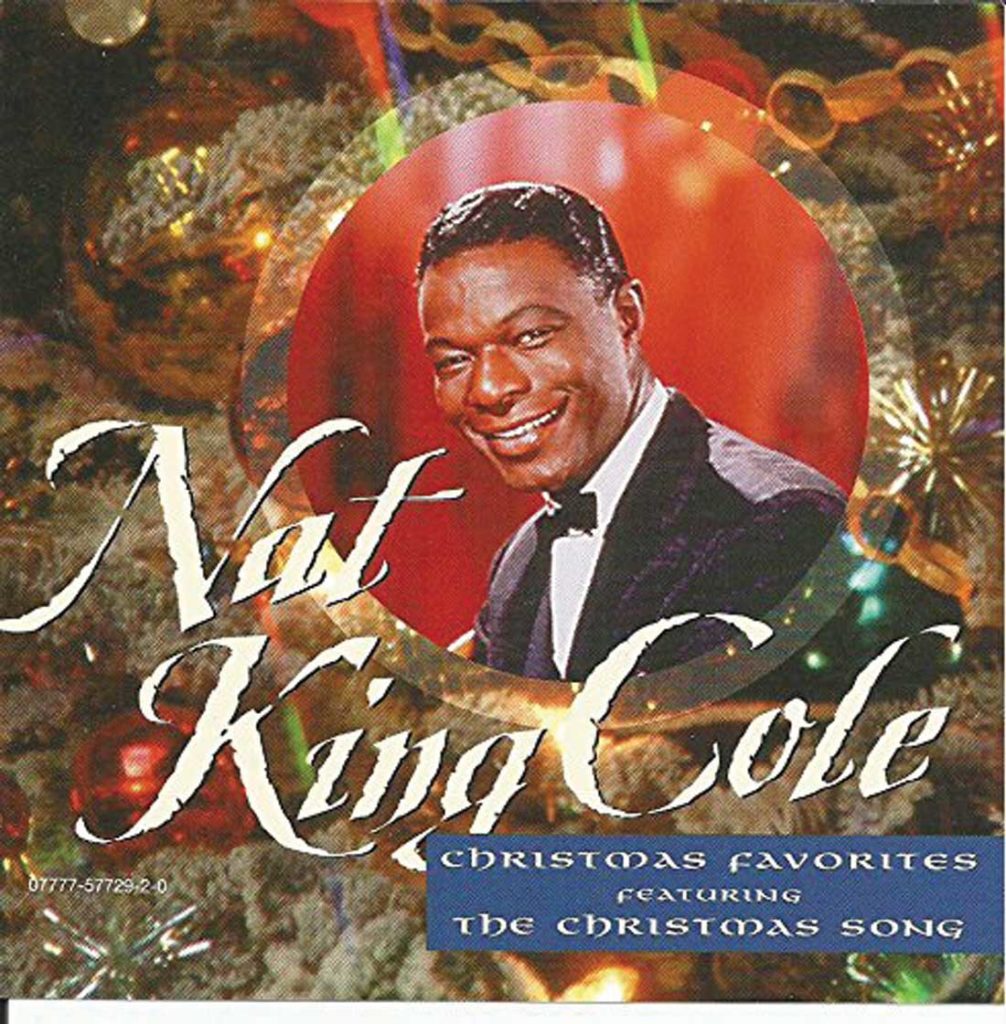

There’s Coltrane, for one. (Yes, I’m counting “Greensleeves” –– the single, not the super-melancholic Africa/Brass version –– and “My Favorite Things.”) And the Rat Pack. And Nat “King” Cole. And Ray Charles. And Otis Redding. And the entire Scrooge soundtrack. And dozens of other indisputably progressive artists who have lent their talents to holiday sounds. (Most not-long-dead singers putting out Christmas music are probably just trying to cash in. You can forget them. Most of them, anyway. The Barenaked Ladies and Sarah McLachlan’s “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen/We Three Kings” medley is decent. And a little Bublé or Harry Connick never hurt anyone. But that’s it.)

There are also the songs themselves, nuggets of catchy, sumptuous melodies (“O Holy Night,” “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen,” “My Favorite Things,” “Greensleeves,” “Linus and Lucy”) and/or clever wordplay (“Sleigh Ride,” “Winter Wonderland,” “The Christmas Song”). The familiar lyrics and/or melodies, in their familiar timbres and hues, have always been a balm of sorts. Growing up as a depressed loner, the last child of four in a crowded house and even more crowded neighborhood that somehow only managed to amplify the loneliness, I coveted “Skating” like a junkie his fix. Interrupt me during A Charlie Brown Christmas at your own peril. I had some foldin’ money from my Pittsburgh Press paper stand but never dared to think I could waltz on down to Jim’s Records to buy the 7-inch –– Jim’s front window was covered with posters of The Cars, The Pretenders, Blondie, Cheap Trick, The Police, and other indisputably “cool” bands from the late 1970s/early ’80s, reflecting owner Jim Spitznagel’s indisputably “cool” taste. Some sappy piano ballad from some kids’ holiday TV show? Hip Jim would have laughed me out of the neighborhood.

There are also the songs themselves, nuggets of catchy, sumptuous melodies (“O Holy Night,” “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen,” “My Favorite Things,” “Greensleeves,” “Linus and Lucy”) and/or clever wordplay (“Sleigh Ride,” “Winter Wonderland,” “The Christmas Song”). The familiar lyrics and/or melodies, in their familiar timbres and hues, have always been a balm of sorts. Growing up as a depressed loner, the last child of four in a crowded house and even more crowded neighborhood that somehow only managed to amplify the loneliness, I coveted “Skating” like a junkie his fix. Interrupt me during A Charlie Brown Christmas at your own peril. I had some foldin’ money from my Pittsburgh Press paper stand but never dared to think I could waltz on down to Jim’s Records to buy the 7-inch –– Jim’s front window was covered with posters of The Cars, The Pretenders, Blondie, Cheap Trick, The Police, and other indisputably “cool” bands from the late 1970s/early ’80s, reflecting owner Jim Spitznagel’s indisputably “cool” taste. Some sappy piano ballad from some kids’ holiday TV show? Hip Jim would have laughed me out of the neighborhood.

What did he know, though. It wasn’t my fault King Cool wasn’t in touch enough with life’s inherent bittersweetness that he couldn’t picture snow falling gently over peaceful trees and houses as those notes twinkled softly. Wasn’t my fault he couldn’t warm to the isolative nature of the song. Wasn’t my fault he was, clearly, happy and contented. And not so alone all the damn time.

Starting in my tweens, I always thought suicide or some other species of early death would be my future. I was only 22 when my father died after a shockingly brief battle with cancer at the age of 61. We buried him on Christmas Eve 1993. Not long afterward is when I cracked. Convinced that a slight bulge in my neck was cancerous, I would sprint up Liberty Avenue to the local E.R., sometimes in the middle of the night. After my fifth or sixth trip in nearly as many weeks, my mother gave up on trying to reason with me and instead started offering comfort. With my dad gone, she and I were the only two left in our old house. Though my brothers and sister had all moved on to their adult lives, my mother still relied heavily on my sister, who was married but lived nearby. Something Virginia casually mentioned one day was really all it took for me to move on. “That kind of thing doesn’t happen to us,” my sister said, meaning that while our family was great, as relatively happy and healthy as the next group of lower-middle-class dagos on the block, we weren’t the kind of family to either win the Lotto or get crushed to death by falling airplane debris in the middle of the night. What she meant was that our family was regular, normal, unexceptional.

What I heard was different. What I heard was that we were divine.

After my first time hearing “I Like Life” from Scrooge, probably when I was in 6th or 7th grade, I sang, “I like life / Life likes me / Life and I fairly fully agree” to myself every time despair landed on me with a thud, which was often, at least daily if not hourly during my tweens, teens, and 20s. “Happiness is just a choice,” I would mutter to myself, alone in my room or in the family car parked in an empty alley, ropes of snot hanging from my tear-clogged face. “It’s just a choice. Please choose it, Anthony. Please choose life.”

Christmas was the only time of year when I felt I was assured that I would not feel or even be alone. No matter what was going on, I always set aside time to be able to enjoy the holiday season, damn it, and the music was a big part of that. Now my favorite Christmas songs remind me of not just happy moments from my past but also the imagined pasts of the performers as they were recording the songs. I am aware that African-Americans and other minorities were treated horrendously when most of this music was written. I’m not talking about that portion of their pasts. As a healthy, white cis male, I’ll never comprehend their pain. What I can sort of make sense of is the connectivity of our shared spaces, psychic and physical. In my childhood, I lived with and among World War II survivors and in and among buildings from the same era. The tangible encapsulation of the passage of time still stuns me. That that silhouette of that church against that empurpled sky or that clanging old radiator in that corner of that store on Liberty Avenue have been experienced or even touched by people who are now long dead and whose lives were probably brutal renders me small, which is right where I should be if I’m going to practice mindfulness – and gratitude.

Trying to be kinder and gentler – not only to strangers and conservative politicians but also to ourselves – can only help us maintain the kind of 25,000-foot perspective that’s needed to navigate life in the West now. As the Ghost of Christmas Present in Scrooge sings, “Ebenezer Scrooge! / The sins of man are huge! / A never-ending symphony / Of villainy and infamy / Duplicity, deceit, and subterfuge!”

But then the giant ghost soon adds, “I must admit / Life sometimes has / Its brighter side as well.”

*****

The same stressors that have plagued me since becoming a parent are still wrapped noose-like around my neck. With one fewer now: Apollo’s ability to read way above grade level is significant because for children like him – a black male in Fort Worth, Texas – not being able to read at grade level by third grade is essentially a one-way ticket to the school-to-prison pipeline. I’m thrilled that he’s well on his way in the opposite, good direction.

My biggest stressor – that he will get in trouble at school – will stay with me until he graduates from Yale (he’s going to Yale), a burden with which I forcefully made peace a few months ago.

This was around the time the Republican-controlled universe passed a tax cut that may benefit the middle-class now but could ultimately spell the destruction of Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security in the near future. This encroaching death by wealth transfer would, naturally, inspire Buddy to volunteer with his family at every soup kitchen in New York City and the North Pole. (Note to self: “Volunteer this summer!!!”) Bob Cratchit, the happiest dude in all of Victorian England, would handle the dismantling of democracy the way most of us will probably have to: After toiling all day in our frigid, soulless boss’ frigid, soulless counting houses, we will go off to our second or third jobs. (Note to self: “polish resume, CareerBuilder.com, bartending.”)

Dana’s dad will continue doing what he does: take off with Mama Boo on extended RV trips around the country and cheer on his fightin’ Texas Aggies while supporting more than a dozen charities. That people as upstanding and truly Christlike as they are voted for that orange gasbag is an even bigger mystery than Scrooge’s 7.5/10 Rotten Tomatoes score. “Scandalous,” as ol’ Bobby C. would say.

What really irks me is that our kids probably wouldn’t understand why we adults – who, theoretically, can do whatever we want, whenever we want, including drink soda, stay up after 8:30 p.m., and drive – are not deliriously happy all the time. “You see,” we’d have to explain to Little Aiden or Little Emma, likely getting down on one knee and holding him or her gently in place with both hands, “there are these places, like Washington, D.C., and Austin, where there are these people who make all these laws, and some of these people don’t like other people because of the color of their skin, the god or gods they choose to believe in, or how much money they make. That’s right. They probably don’t like you, sweet, sweet, innocent child, because your skin color is dark. Even though they don’t even know you, they don’t like you.”

I don’t like being mopey or even being considered mopey, by anyone but especially by my kid. I just want what I feel on the inside –– joy tempered by slightly sub-par expectations –– to come through on the outside. I want my heart and body to be in alignment. I want to achieve “om.” (Is that still a thing?) Being like Bob helps. Being kind. Being patient. Being mindful. To help me feel as if I’m as drunk on the milk of human kindness as Scrooge is in the musical when he meets the Ghost of Christmas Present, I do what no other lefty adult white males that I know do: I set the mood.

I’m sure you think your favorite version of “A Christmas Carol” is better, but, oh, how wrong you would be. I’ve seen all of the movies at least twice. I’ve also seen about 10 stage adaptations, including on Broadway, and my wife and I still read the story together before bed every Christmastime. The 1970 movie musical remains king. Starring the great Albert Finney in the title role (that earned him a Golden Globe for Best Actor), Scrooge is funny, serious, ebullient, and sad, all in equal measure and all while laced with beautiful song. “Thank ya very much” indeed, Leslie Bricusse.

This Bob Cratchit, played by David Collings, never lets his children know or even sense how bad things truly are. A typical scene is near the middle when “Robert Cratchit, Esquire” –– as he’s mockingly referred to by the Ghost of Christmas Present to prove a point to Scrooge –– is preparing Christmas dinner in his family’s shack. Holding aloft what appears to be a large duck carcass, the cheerful dad says to his children, who have gathered ’round, their faces glowing, “The only remaining problem is whether to put the stuffing inside the goose or the goose inside the stuffing!”

This Bob Cratchit, played by David Collings, never lets his children know or even sense how bad things truly are. A typical scene is near the middle when “Robert Cratchit, Esquire” –– as he’s mockingly referred to by the Ghost of Christmas Present to prove a point to Scrooge –– is preparing Christmas dinner in his family’s shack. Holding aloft what appears to be a large duck carcass, the cheerful dad says to his children, who have gathered ’round, their faces glowing, “The only remaining problem is whether to put the stuffing inside the goose or the goose inside the stuffing!”

The kids crack up. Mrs. Cratchit beams. And I’m like bah humbug. The only times I make my family laugh is when I mispronounce a simple word or do something boneheaded like mow over one of those little metal flags that city workers put in your yard for some reason. (Capsule review: Yowza! That’ll wake ya up.)

The ending to It’s a Wonderful Life is pretty inspiring to the point of tears, sure. I’m thinking specifically of when war hero Harry Bailey raises a glass and says, “To my big brother George, the richest man in town.” Hard not to get even a little choked up at the tsunami of karma that washes over Jimmy Stewart’s iconic penny-loan officer. But as life-affirming as that scene is, it doesn’t affect me as relentlessly or as easily as the one toward the end of Scrooge. It’s after Ebenezer wakes up from his dream and, realizing he hasn’t missed Christmas Day, storms out into town to begin buying presents for everyone. At the toy store, he loads up the shopkeeper’s arms with dolls, boats, paddles, musical instruments –– a mound of wooden, metallic, stuffed glee that goes all the way up to the guy’s nose. Scrooge asks how much everything costs before quickly answering himself. “Oh, never mind!” he says, dropping a few sovereigns into the mound. “And you can keep the change!” Scrooge goes on to say that he will need the services of several “small boys” to help “to transport these delightful objects to their destination, and each boy shall receive a half a crown!” The shopkeeper agrees, his face distorted into confusion and his eyes wide and darting all over the place, because like every other shopkeeper in town, he has dealt with Ebenezer Scrooge, the miserly, bitter old man who owns every inch of real estate in this part of London. “Mr. Scrooge,” the shopkeeper says kindly, his face finally unfolding. “What has happened?”

“Well,” Scrooge replies, joy sapping him of breath, “what’s happened is perfectly simple, Pringle. I’ve discovered that I like life.”

The last time I watched Scrooge with my son was a day or two before Christmas. He was sitting on my lap, and while I was trying not to cry at this scene and at the other one near the end, when Scrooge promises the Cratchits that he’ll pay for Tiny Tim’s medical treatments, I relocated Apollo to my side to keep my fluttering torso from bothering him into asking any uncomfortable questions. It didn’t work. I was still sniffling.

“What’s wrong, Daddy?” my son asked.

“What?” I said, pretending I had no earthly idea what he was talking about.

“Are you sad?”

“Well, no,” I said, trying to sound cool. “I’m not sad. I’m actually just really happy.”

“Like the nice old man?”

“Yes, sweet boy,” I replied, my eyes drier. “Just like him.”

Every time I’m in the car, which is pretty much the only time I’m alone-alone, with only my phone to interrupt me, I set my Pandora app to “Bing Crosby (Holiday),” “Instrumental Holiday,” “Swingin’ Christmas,” or “Fantasia on Greensleeves.” Every time I power up my laptop, I either open one of my streaming stations or cruise to the Scrooge soundtrack on YouTube. I need something to mute the silence. For me, the silence almost always leads to the darkness. It’s either paralyzing existential dread or me checking my phone every 30 seconds to see if Apollo’s school or the Y has called (or logging onto Twitter every other minute to see if World War III has started). As a too infrequent music critic back in the day, I loved being exposed to new tunes. Now, contemporary sounds are a luxury from whose immaculately radiating brilliance I must scurry away in complete unworthiness like a cockroach after the kitchen light has been turned on. Am I worried that my family will be celebrating Christmas all year long? A little, because that would be super-weird. But because so much that has to change between then and now is mostly out of my control, I can’t be bothered by worrying about it to death. What was it the Buddha said? *goes to fridge* “Do not dwell in the past, do not dream of the future, concentrate the mind on the present moment.”

Or as Scrooge’s Ghost of Christmas Present says: “There is never enough time to do or say all the things that we would wish. The thing is to try to do as much as you can in the time that you have. Remember, Scrooge. Time is short, and, suddenly, you’re not there anymore.” l