When one is in the nosebleed section of the human lifespan, not returning a phone message for days can be worrisome. When I had spoken to Jerre Todd a few weeks earlier, the affable former reporter had been eager to set up an interview about his days at the old Fort Worth Press, an un-air-conditioned Scripps-Howard sweatshop whose newsroom had somehow managed during the 1950s to incubate some of the greatest sportswriters to have ever been shamelessly plagiarized by other sports journalists. They included Todd himself, as well as Gary Cartwright, Dan Jenkins, William Forrest “Blackie” Sherrod, and Bud Shrake.

Jenkins, Shrake, and Todd graduated from Paschal High School and TCU. Cartwright also graduated from that university.

Todd founded a successful public relations agency after leaving sportswriting, and Sherrod was for decades a newspaperman of legendary proportions. But Cartwright, Jenkins, and Shrake collectively went on to write screenplays, bestsellers that were adapted for the big screen, and columns and articles for magazines such as Playboy, Sports Illustrated, and Texas Monthly. Their associations with the famous and infamous ran the gamut from Jack Ruby to Julia Roberts.

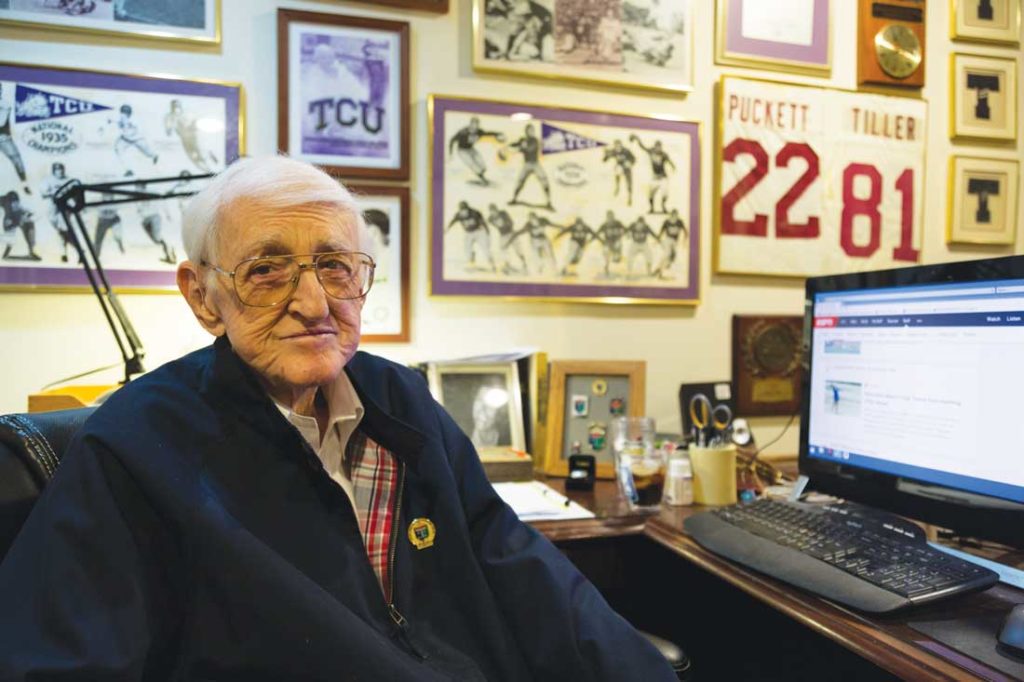

Of them all, only Jenkins and Todd remain. Todd is 85. Jenkins turned 88 on Dec. 2.

The Fort Worth Press itself was the first to go. Its press fell silent on “Black Friday” –– May 30, 1975 –– “years after rigor mortis set in,” Cartwright wrote in a memorable obituary for Texas Monthly. Scripps-Howard executives jerked the plug after decades of the newspaper turning little or no profit, even though the parent company was said to have done little to help it succeed.

Marshall L. Lynam, a former Press reporter who later served as chief of staff for House Speaker Jim Wright, wrote in his 1998 book Stories I Never Told the Speaker: The Chaotic Adventures of a Capitol Hill Aide, that pennies were pinched to such an extent that reporters were required to turn in the stub of a copy pencil before they would be issued a new one.

“And once when a reporter rode with sheriff’s deputies to a crime scene out in the suburbs and then asked how to get home, the City Desk told him to hitchhike,” Lynam wrote. He died in 2012.

There was no such thing as Christmas bonuses at the Press. Every year the hundred or so employees would draw for one company Christmas gift, which was something along the lines of a box of candy.

Shrake’s keyboard fell silent in 2007. His accomplishments include a lifetime achievement award from the Texas Institute of Letters, induction into the Texas Film Hall of Fame, and co-writing the bestselling sports book in publishing history, Harvey Penick’s Little Red Book (1992).

Sherrod, whose gift for reporting and writing landed him assignments covering the 1960 Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy, and the 1969 Apollo moon landing, died in 2016, five years after being inducted into the Texas Newspaper Hall of Fame. He had authored three books.

Cartwright is the most recent to have –– as Jenkins put it –– “called a cab.” He died in February, seven years after his retirement from Texas Monthly. He had worked at the magazine since its first issue in 1973 and helped it reach national acclaim. Like Shrake, Cartwright was the recipient of a lifetime achievement award from the Texas Institute of Letters.

I had just started worrying about Todd when, at dusk on a Saturday evening, I received a call from a woman who identified herself as his wife, Melba. She explained that he had fallen a few days earlier and was recuperating in a rehab facility. The interview was delayed but luckily did happen.

Jenkins, too, agreed to an interview, but asked to respond to questions via email. An intermediary explained that Jenkins has some hearing difficulty.

The two men, friends since their days at Paschal, shared memories of an era in journalism that is long gone –– when newsrooms were full of tobacco smoke and clacking teletype machines.

“That’s exactly how it was,” Todd said of the newsroom at the Press. “We made it so much fun.”

The Associated Press once quoted Shrake’s description of the Fort Worth publication.

“It was a rackety, dirty city paper, with the teletypes clacking and a sense of urgency everywhere,” he wrote. “A copy editor was eating tuna fish out of a can, and the bowling writer was drinking bourbon, and I thought, ‘This is the world I want to be in.’ ”

Jenkins said that the Fort Worth Press’ newsroom “was what Hollywood could have created. Dense with cigarette smoke, much of it mine, noisy, grimy, cold when it was cold outside and hot when it was hot outside. But great fun and laughter abounded. I give thanks every night that I came from an earlier era.”

*****

The first issue of the Press hit the streets on Oct. 3, 1921, with a lead story about a Ku Klux Klan parade near Waco that had disintegrated into a riot, injuring 10 men, including the McLennan County sheriff. That pretty much set the tone.

The newspaper sold for 3 cents per copy. Subscribers paid 12 cents per week to have their paper delivered or $4 per year to have it mailed. At first, the fledgling newspaper’s offices were on Commerce Street, in the space that would later house the Greyhound bus terminal. In 1926, the operation moved to a two-story tan building at Jones and 5th streets, which is now occupied by the Fort Worth Police Department.

From the beginning, the newspaper faced financial challenges. It was just one of many Scripps-Howard newspapers, whereas its competitor, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, was the only baby of then-publisher and civic donor Amon Carter.

Jenkins said that, with the exception of the sports department, the Press was probably “one of the worst” newspapers in the country. Tommy Love, who covered TCU and the Texas Rangers for the Press in the early 1970s before leaving in ’74 to take a job in TCU’s athletic department, said that the news section “was more like the National Enquirer. The front page may be something about a small child locked in a refrigerator or something.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. A headline from a Press clipping whose date cannot be distinguished reads, “PYTHON LOOSE! Man-Killer Out of Cage.” And just in case that wasn’t dramatic enough, there was this subhead: “He’s Probably Hungry, Too.”

“We went with sensationalized stuff on the front page of the Press,” Love continued. “We weren’t going to compete with the Star-Telegram. We were going to lose that battle every time. So if [we] could get somebody’s attention with a headline like a cow with three heads is found in Argyle –– that would be our lead story.”

The Press did write about other things, even political corruption, Love said. It also sponsored the annual spelling bee for the Fort Worth school district and the Golden Wedding Party for couples who had been married 50 years. Cartwright wrote that the paper managed to plod along for decades after the first rumors of its looming demise began circulating. Even in uncertain times and with a lean budget, the Press usually managed to whup its competition at sports coverage, even if it didn’t beat them at anything else.

The late journalist, novelist, and playwright Larry L. King, who co-wrote the Tony Award-nominated play The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, called Sherrod “the most plagiarized man” in the state and wrote that he held the Press’ sports department together “with chewing gum and bailing wire and cussing.”

Todd said the department was recognized as one of the best sports departments in the state of Texas.

“I think Blackie had a lot to do with it,” he said. “He knew talent and would offer you a job at the Fort Worth Press. He was a real magnet, Blackie was.”

He added, “I must say, we were pretty good.”

*****

Timing, they say, is everything, and it may hold a clue as to why an assemblage of young sportswriters at the Press ascended. Their careers might have taken more mundane paths had the Press not been an afternoon paper. There was a mid-morning issue that went to the outlying suburbs, but the real focus was on the “city final” that hit the streets around noon.

Former sportswriter Love believes that the deadlines for Fort Worth’s competing newspapers played a role in how the Press came to dominate in sports coverage. By the time the Press hit the streets, most people already knew the score and might have already read the Star-Telegram’s story about the game, he said.

“By the time the Press came out, people already knew the basics,” Love said. And so we were allowed to go more in depth or come up with a funny lede. We weren’t stuck with that formula of who, what, when, where, why, and how. People wanted to hear strange details or funny quotes or whatever. So it really gave you a freedom to explore or head off in other directions or be entertaining.”

The Press’ writers were at the games, just as the Star-Telegram’s were, Love said, but the Star-Telegram’s reporters had to rush to get box scores and meet deadlines. Not so much where the Press guys were concerned.

“We were there keeping up with the game and knowing all that was happening, but we were noticing things throughout the game,” Love said. “And so when the game was over, we headed to the dressing room and talked to the players and talked to the managers, whereas the Star-Telegram people had a deadline, and they had to get all their stuff in at a certain time for the morning paper.”

He continued, “We’d get to work at 5:30 in the morning or 6 o’clock in the morning and start writing our stories if we didn’t stay up that night and write it. It was a lot more freedom. It allowed you to be creative. I think that’s why [some Press sportswriters] launched off into books.”

Gary Cartwright seems to have shared that view. In his 1983 book Confessions of a Washed-up Sportswriter: Including Various Digressions about Sex, Crime, and Other Hobbies, Cartwright wrote of his days at the Fort Worth Press when he would arrive for work before dawn. “The morning dark,” he wrote, “does things to the creative man.”

The same creativity that infected the sports department did not spread to other areas of the newsroom, “but the sports department would compete head-to-head with the Star-Telegram, and, of course being biased, I thought we consistently beat them,” Love said.

Jenkins credits the Star-Telegram with having been strong competition that inspired the Press crew.

“I mean, their sports staff was really good, and so was the whole paper,” he said. “I’m sorry that there are so many people who don’t remember when the Star-Telegram was the best damn newspaper in Texas.”

By the time Love joined the staff at the Press in 1970, just 21 and freshly matriculated from Texas Tech, the greats from the ’50s were long gone. Jim Browder was the sports editor, Delbert Willis was the editor, Mike Shropshire was the star sports writer (“Maybe the funniest writer I’ve ever read,” Love said), and the damn building still wasn’t air-conditioned.

*****

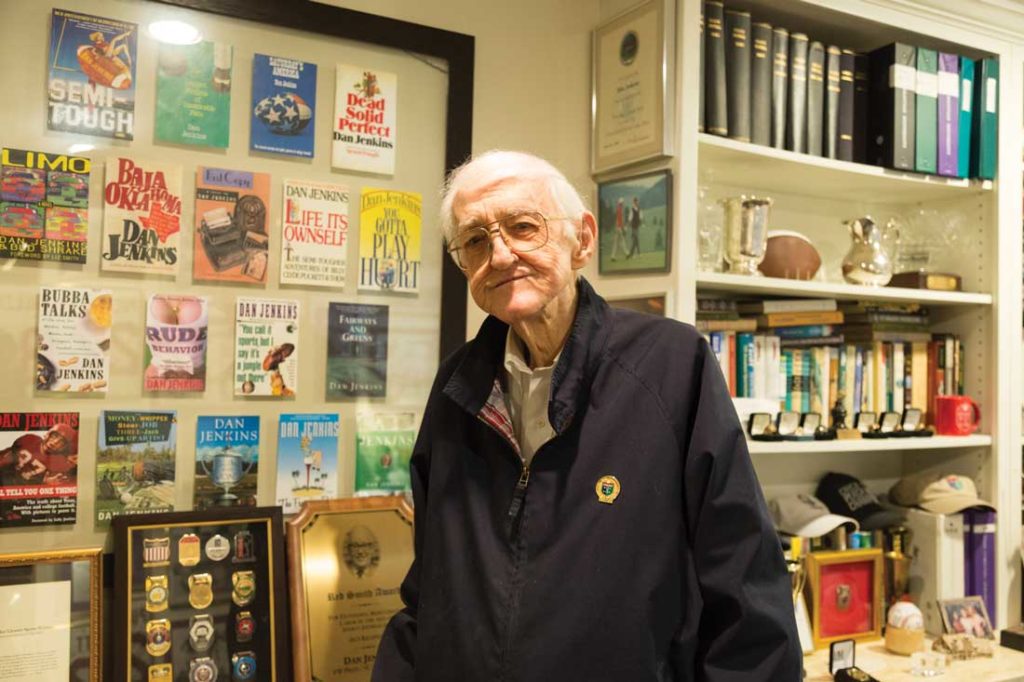

Earlier this year, the Moody College of Communication Texas Program in Sports and Media at the University of Texas announced the creation of the Dan Jenkins Medal for Excellence in Sportswriting, an award that will be given annually to two honorees.

At the October ceremony, a career achievement medal was given posthumously to Frank Deford, a Sports Illustrated writer and longtime NPR sports commentator who died in May. Wright Thompson was recognized for his 2016 ESPN The Magazine piece “The Secret History of Tiger Woods.”

A third medal was presented during that inaugural ceremony, and it went to the award’s namesake. Sally Jenkins, a sports columnist for The Washington Post and co-chair of the medal committee, presented the medal to her father.

Though he has worked for seven decades and is closing in on 90, Jenkins is still writing. He continues to cover the PGA’s major championships for Golf Digest, and his 24th book, a sports/humor collection, is scheduled for publication next year.

From the get-go, it seems, Jenkins was destined for success.

His first novel, Semi-Tough, published in 1972, was a bestseller. The story about a love triangle involving two professional football players was made into a movie featuring big-name stars from that era –– Burt Reynolds, Kris Kristofferson, Jill Clayburgh, Burt Convy, and Brian Dennehy.

Jenkins went to work for the Press in the summer of 1948, right after graduating from Paschal and before starting his freshman year at TCU, where he would play varsity golf. He landed the gig, which paid $25 per week, without having to sweat through an interview with the intimidating Sherrod. The crusty editor offered him a position after seeing a humorous piece he had written for the Paschal Pantherette.

“I entered TCU with a byline,” Jenkins said. “As I’ve said, that might make some young man arrogant if he hadn’t received proper training in the home.”

When Shrake graduated from Paschal a year after he did, Jenkins helped him get a job at the Press. He did the same for Todd in 1952 when Todd was attending TCU.

In an article for the December 1975 issue of Texas Monthly about Blackie Sherrod, “The Best Sportswriter in Texas,” Larry L. King wrote, “Sherrod still considers Todd the big one that got away. ‘He might have been better than any of us if a living wage hadn’t been so dad-gummed important to him.’ ”

Todd said that, even though he “loved every day” at the Press and “hated to go home,” he quit because of a new invention: color TV. “I had to have one, and I could never afford one working there,” he said.

Todd left the newspaper in 1959 to take a job in public relations, ultimately starting his own business. The Arlington-based Todd Company is now run by his son, Britt Todd.

It has been 65 years, but Todd still remembers the day he met up with Jenkins at the Press for his big interview with Sherrod. At that time, the newspaper needed a baseball writer.

“We were standing at the top of the stairs of that little square building that was built in 1920 or 1930,” Todd said. “I asked Dan Jenkins, ‘Which one’s Blackie?’ Then I take off running from that upstairs entry across the city room, into the sports department, and I did a hook slide into Blackie’s feet, like I was sliding into second or third base. He looked down at me and said, ‘Hired.’ ”

Todd covered baseball, but wrote about other things, too –– all while juggling classes and contributing to TCU’s student newspaper.

“We had some real characters on our sports staff,” he said.

One of them was a man named Puss Ervin, the bowling writer. Ervin, Todd said, had a habit of stripping down to his underwear to write his stories because the newsroom was so hot and humid. Cartwright described that scene in his obituary of the Press for Texas Monthly. “Puss,” he wrote, “had removed his shirt and was sitting in some BVDs that looked as though they’d been washed either two or three times since the New Deal.”

Jenkins graduated from TCU in ’53 “with a degree in either journalism or English, I’ve forgotten which.” It took him five years because of the work he was doing for the Press.

After Sherrod left in ’58 to write a column for The Dallas Times Herald and serve as sports editor there, Jenkins took over as sports editor at the Press. In 1961, he followed Sherrod to The Herald, where he took on sports editor duties and served as a “second columnist” so that Sherrod could concentrate on his own column and his new duties as assistant managing editor. Jenkins’ stint at the now-defunct Dallas paper was short-lived. He left in ’62 after being offered a job at Sports Illustrated.

“It was my ambition to make it to New York as a sportswriter,” he said.

Jenkins worked for SI for a quarter century, taking early retirement in 1985 and taking on two new gigs: writing a monthly sports column for Playboy and writing a golf column and features for Golf Digest. The Playboy job lasted five years.

“I’ve enjoyed every day of my life because I chose a profession I love,” he said. “The most fun was newspapers, but Sports Illustrated in those glory days of the magazine was a great 25 years. It was a swell calling card. It sent me all over the world, let me cover my two favorite sports, golf and football. What’s not to like? Manhattan was great then, too.”

As Todd was thriving in PR and Jenkins was enjoying his success in the sportswriting profession, Shrake and Cartwright were becoming known as two of the best writers in Texas. For a time in the early 1960s, they shared an apartment in Dallas. Frequent late-night visitors were nightclub owner Jack Ruby and one of his top strippers, Jada, whom Shrake dated. Cartwright wrote in Confessions of a Washed-up Sportswriter that on the morning of President Kennedy’s assassination, Ruby phoned the apartment to ask whether the two sportswriters happened to know of Jada’s whereabouts.

Two days later, Ruby shot and killed Kennedy’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald.

Ruby frequently appeared in Cartwright’s literary works. He once wrote of the nightclub owner, “If there is a tear left, shed it for Jack Ruby. He didn’t make history; he only stepped in front of it. When he emerged from obscurity into that inextricable freezeframe that joins all of our minds to Dallas, Jack Ruby, a baldheaded little man who wanted above all else to make it big, had his back to the camera.”

Shrake would later spend 17 years as the companion of Texas Gov. Ann Richards until her death from esophageal cancer in 2006. He escorted her to her inaugural ball and presided over card games inside the governor’s mansion.

During the 1980s, he wrote as-told-to biographies of Willie Nelson and Barry Switzer. He wrote four books with golf professional and coach Harvey Penick, who died in 1995, and 10 novels. His screenplay credits include Tom Horn, a Western starring Steve McQueen and written in collaboration with Thomas McGuane in 1980. He played a bit role in 1991’s made-for-TV movie Another Pair of Aces, which he co-wrote with Cartwright, and appeared as “Sodbuster Two” in Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove.

Jenkins and Shrake co-wrote Beverly Hills Cop II and Jenkins’ Baja Oklahoma was Julia Roberts’ first role.

Referring to Shrake, he said, “We both wrote several screenplays that never got made. That’s Hollywood, but I enjoyed becoming friends with James Garner, Jack Lemmon, Burt Reynolds, and so on. Too many to count.”

In 1998, the boundary-pushing, hard-living Cartwright wrote a memoir titled HeartWiseGuy about a life-changing heart attack. In 2015, he published another memoir, The Best I Recall.

A story in The New York Times about Cartwright’s death quoted Joe Holley, a columnist and editorial writer for The Houston Chronicle. He said that Cartwright and other Texas writers with whom Cartwright had been associated “lived hard,” were good writers, and “seemed to be intensely alive.

“What we didn’t realize until later,” Holley told The Times, “when the heart attacks began and when they started writing confessional memoirs, was that hard living exacted a price.”

Heavy drinking, smoking, and, at least in Shrake’s case, the use at times of illicit drugs are part of the story where the old Fort Worth Press gang is concerned, though Jenkins disavows it for himself.

“All that boozy living is bullshit where I was concerned,” he said. “I never drank at home in the daytime or while writing. I only drank socially or, as they say, to make other people interesting.”

Cartwright was 82 when he died earlier this year at Seton Medical Center Austin after falling inside his Austin home. His granddaughter told The Dallas Morning News that he had spent four days on the floor before being found by a neighbor.

Shrake’s death, too, on May 8, 2009, occurred in Austin. He was 77 and had spent several years battling prostate cancer and lung cancer.

Todd said that in the weeks before his death, Shrake stayed with him and Melba at their Arlington home after having surgery at a Fort Worth hospital. He said that during other stays there, when Ann Richards was still alive, she would phone the house to talk with her close longtime friend.

“I recall the phone would ring every other day, and this husky voice would be on the other end of the phone,” Todd said. “She’d say, ‘This is Ann. Is Bud there?’ That always touched me.”

As for Sherrod, the cab took its time coming. He suffered from dementia for 10 years before dying at his Dallas home on April 28, 2016. He was 96.

*****

Todd said he was both surprised and not surprised when the Press closed its doors.

“I thought there’d always be a Press,” he said, even though the persistent rumors that the corporate office was going to pull the plug never went away.

“We’d been hearing that the Fort Worth Press was a tax write-off for Scripps-Howard,” he said. “I don’t know how true that story was, but that had been circling around for a long time.”

Not only was the Press an afterthought for Scripps-Howard, it was as well for the city of Fort Worth, in Tommy Love’s opinion. He retired in the summer of 2016 as TCU’s assistant athletic director for business and finance.

“At the time, I doubt that Fort Worth realized what they had when they had Blackie and Dan and Bud Shrake and that whole group,” he said. “You know, the circulation was never that high. I just don’t think, at the time, the people in Fort Worth realized what a special time in sports history that was. It wasn’t until years later, when Blackie had been at The Dallas Times Herald for 30 years or whatever and was considered one of the greatest writers in sports writing and Dan was writing books and Bud Shrake was writing books and Gary Cartwright was writing books. It was an unbelievable time. And, yes, I realized the history of that department, and I was still seeing it with writers like Shropshire and Jim Browder. But it definitely didn’t reach the zenith of that ’50s era.”

Todd said he was at his office, which at that time was in Fort Worth, when he heard that the Fort Worth Press was publishing its final issue. Editor Delbert Willis’ 72-point headline at the top of Page 1 read, “Farewell, Fort Worth.”

“I went to the corner of Throckmorton and 7th streets and picked up a Fort Worth Press rack that they put papers in,” he said. “Just took it. Kept it for years. I put it outside my garage door for 15 years. Every once in a while, a sucker would come up and drop a dime in, trying to get a paper out.”

Both Todd and Jenkins are sad, of course, about the deaths of their friends. But they are also sorrowful over the passing of the Fort Worth Press and other newspapers.

“It was a wonderful institution,” Todd said of the Press, “and it will never be replaced in Fort Worth.”

Jenkins said, “I’m sad to watch my kind of journalism slowly dying and daily papers along with it. I loathe and despise fake news and social media and young people who care nothing about history.”

Cartwright summed up the important role the Fort Worth Press played in his life in one succinct sentence in Confessions of a Washed-up Sportswriter.

“Almost every important thing I learned,” he wrote, “I learned at the Press.” l

Amen to Jenkins comment about fake news and the young having no regard for history.

I appreciate ths remarkable review of obviously smart and hardworking writers. i lived with my Uncle Fred Fletchner in Dallas when he worked

for the Dallas Morning News as a cub reporter in the early 1930s.. I understand, with a childs mind, those times that were filled with more leisure activities in families. Listening to baseball over the radio as the strikes and balls were announced For the minor league games of six teams. I have appreciated knowing Jerre Tod as a friend and his sons Brooks and Britt and wife Melba. An association that included going each Sunday to an Adult Forum Bible Study. It has hurt watching many good people go home to our Lord.. My wife and I are in our early nineties. God Bless. John Adam – author Flechtner on Facebook.

Maybe the best article ever published in the Weekly. Great job, Kathy.

What a fantastic story, well done

Thanks for a great article! I am proud to say that my first job as a kid was being a paperboy for the Fort Worth Press, and my first job out of college was working for Jerre Todd himself.

A transplanted Okie, I first crossed paths with several of these men nearly 40 years ago. I’m definitely richer for knowing them.

And one night in 1993 at Elaine’s Restaurant in New York City with Dan and Bud stands out as a surreal experience I’ll never forget: Dan introducing me to his friends Leslie Nielsen, George Plimpton, and many other luminaries, and the proprietress treating our party like royalty.

Kathy – You captured your subjects. Well written.

Upon graduating Paschal H.S. in 1966, I went to work for Jerre R. Todd, hisself. Worked for Todd & Assoc. As an intern while studying journalism at UT Austin for five years ( also mastered shuffleboard and Budweiser 301). With Todd as headmaster, I received the benefits of association and education from the best – Jenkins, Shrake, Cartwright, with Elston Brooks, Mike Cockran thrown in for good measure. I always appreciated these gentleman, for they taught me “how to and how not to”. The Best of All Time.

Thank you for your article.

Reading old issues on microfilm is a delight. Dan Jenkins sports writing was colorful, alliterative and fun.

Talk about headlines in the Press, I remember when President Kennedy was shot and killed in Dallas, one of the headlines in the Fort Worth Press a couple of days later was “TCU – Rice Owls game has been postponed (maybe cancelled) because of Out of Season Shooting in Dallas!”

Never will forget reading that as I was in my sophmore year at TCU!! Great article on these great writers !!! Thanks for sharing!!!

Kathy Cruz:

I was a reporter/feature writer at the Fort Worth Press during the later 1950’s. I began as the police reporter in 1954 after being graduated from TCU. Willis was city editor and an amazing one who lost a leg in WWII but scooted about the newsroom on a castered stool propelled by one of his crutches. As good as he was, he was often up staged by his assistant city editor Mary Crutcher, my immediate boss and re-write specialist. I learned more journalism from her than I had in four years of college. Anyway, I know and partied with all the sportswriters you mentioned. They were as good as you got but most of the paper’s writers were exceptional because we became masters of the “second day lede” usually forced to follow the staid old morning Star Telegram. BTW, I was the staffer picked too report on the hunt for Pete the Python and was pictured in a canoe under a pith helmet scouring the brambles along the Trenity River. Great memories.

Clyde J. Moore

I remember Blacky Sherrod when he was writing for the Dallas Times Herold. His column was the first article that I looked for in that newspaper. He was such a great writer.

Loved the memories this story evoked. My late husband, Jim Marrs, worked at the Star Telegram and was friends with all the Press reporters. He worked for Jerre Todd’s Advertising Agency after we moved to Wise County in the ‘80s because we couldn’t afford our mortgage payment on his reporter salary. I’ll always be grateful to Jerre for hiring Jim and giving us the opportunity to get out of the city.

It is a tragedy that this generation will never read print the quality created by these people. Wall Street has killed Broad Street and we are poorer for it. Wonderful article about some people who brought sports (and life) alive.