The piercing ding of my iPhone at 6:13 a.m. on June 1 barely registered while I sleepwalked through my weekday routine before work. I glanced at the screen with bleary eyes to see who was texting me at this ridiculous hour, saw it was my best friend Kyle Trentham, and thumb-scanned my way to Messages.

“Wow,” he wrote. “Rainbow literally up in flames.”

And then a few seconds later, with that same slightly inappropriate, grim tinge of humor that had cemented our friendship all those years ago when we first met at the Rainbow Lounge, the place to which he was referring, a single word appeared.

“Finally?”

My brain was stuck in a buffering loop at that hour, so I reached for my laptop and did what any logical human being would do when faced with unthinkably impossible news: I opened Facebook. And right there, at the top of my news feed, in a shared tweet from earlier that morning, was video footage of the Rainbow Lounge, Fort Worth’s legendary Near Southside gay nightspot and lightning rod for political controversy, engulfed in a blazing fireball while the shaky-handed bystander filming the inferno on his smartphone sputtered expletives of disbelief.

I sputtered a few of my own.

A few hours later when I was standing outside the smoking wreckage of this once-famous (or infamous, depending on whom you asked) LGBT watering hole – the acrid smell of scorched wood burning my nostrils; the constant drip, drip, drip off crumbling, water-drenched brick filling my ears – the reality of what had happened began to sink in. Oddly, my reaction was more subdued than I expected.

*****

The previous few weeks had already been a dizzying nightmare. My husband and I had just returned from a bloodwork appointment down the street. More than two weeks earlier, Doug had received a liver transplant, so this sudden intrusion of flaming reality was a seismic surprise after the exhausting monotony of hospital visits, medication scheduling, and sleep deprivation. It dawned on us only while we were picking up a chunk of masonry as a souvenir that our 24th anniversary was the next day.

Time creeps up on you like that. I’m sure that the patrons who, just the night before, had guzzled drinks, laughed at off-color jokes, and danced to pounding pop music at this place where they’d shared many nights of their young lives – a group oasis – did not consider it might not be there for them the next evening.

My own perspective had been severely challenged weeks earlier. I sat alone in a hospital room in Dallas terrified and choking back sobs while worrying that the person with whom I had spent most of my adult life – my personal oasis – might not be there for me the next evening. Perhaps that emotional test had inoculated me for this shock.

How could the loss of a building compare to that, right?

As the day wore on, the historical resonance of the tragedy began to drip, drip, drip into my thoughts, distracting me from work and drawing me back to a former preoccupation, bordering on obsession, with the history of Fort Worth’s gay nightlife.

Did you know that since the late ’60s, Fort Worth was home to more than 70 LGBT clubs, nearly 90 if you include all of Tarrant County? I did, because I spent months counting every damned one of them.

But I knew one place better than any of them. I had spent more nights there than I can count and even more than I can remember. I watched it go through multiple owners and three names. It was my home away from home, where I met some of my greatest friends, both long-term and sometimes only for a single night. It was a tobacco- and cologne-scented Neverland where free-flowing booze fueled some of my greatest memories … and also one of my worst. And now, that place was gone.

That morning, I had witnessed this mythical, self-conflated Shangri-La reduced to a giant, brick-walled ashtray and more than 30 years in the word business suddenly left me without access to a single one.

“Finally?” the text had said.

To provide some perspective on where this place fits in our collective history – and I’m speaking in the gay “we” voice now – I turned to The Files. One thing about being an anal-retentive archivist is that you’re never happier than when doing research. I live to create timelines, alphabetize materials, and, most importantly, put scraps of paper ephemera into acid-free plastic sheet protectors. I had assembled a biblically thick dossier on the city’s nearly 50 years of open, gay nightlife, so here beginneth the lesson.

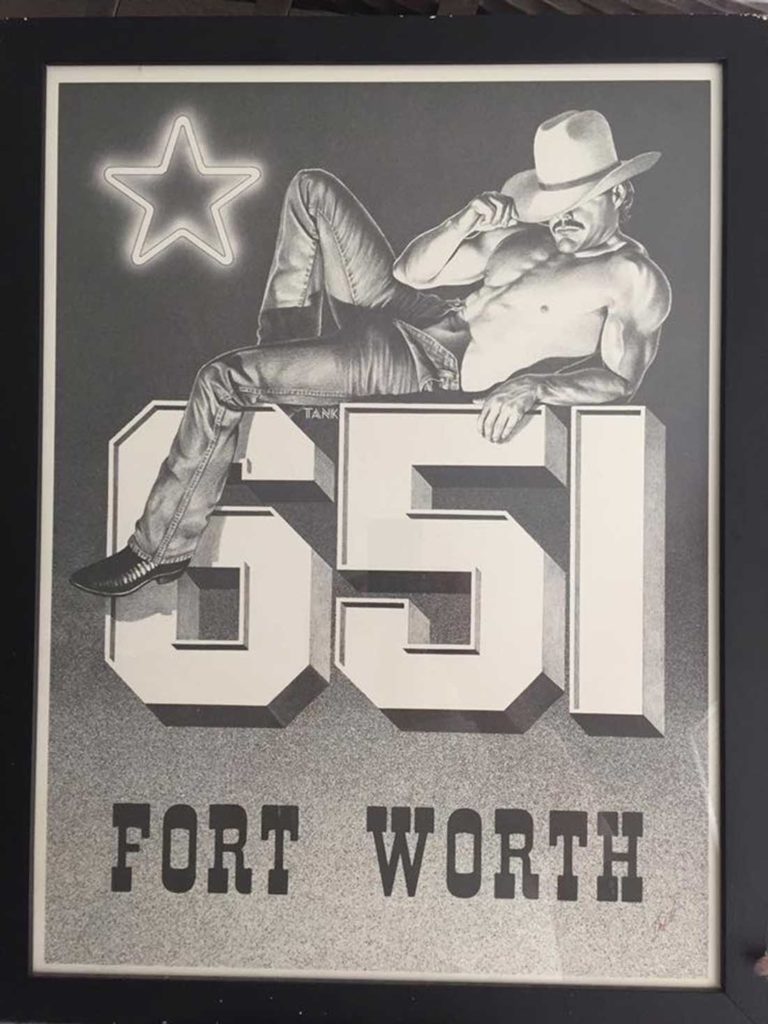

Long before the Rainbow Lounge dropped its first beat, there was the 651 Club (named for its street address), which opened in February 1969. A few months later that year, in a gay nightclub called the Stonewall Inn in New York City’s far-from-gentrified Greenwich Village neighborhood, the patrons – a motley crew of drag queens, transgender folks, rent boys, and other outcasts – were still in mourning over the loss of gay icon Judy Garland. When police tried to raid the bar for the umpteenth time on the night of June 28, 1969 (the night of my third birthday, by the way), this urban isle of misfit ladyboys fought back, and the ensuing series of riots over the next few days would give birth to the modern gay rights movement.

Not that those melees meant much to the still-closeted queens in Cowtown. The folks at the 651 that same summer night in Fort Worth probably had no idea what their Yankee brothers and sisters were starting several thousand miles away. Though 40 years later, the folks in a new bar, with a new name but in the same old building, would get a small taste of it themselves. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The lot at the corner of South Jennings Avenue and West Hattie Street already had a history. In the late ’10s and ’20s, it was home to a two-story boarding house and in the years to come would play host to everything from a barber shop to a television repair business. In the mid ’60s, the building was split in half –– on one side, the Jennings Avenue Washamatic and the other, a short-lived dive called The Sportsman Lounge. In 1967, a classified ad in the Star-Telegram hawked several lounges for rent, including one at 651 S. Jennings Ave.

Late-’60s gay nightlife in Fort Worth was practically nonexistent. For those unwilling to drive all the way to Dallas, your options were limited to making the trek up Jacksboro Highway to the tiny town of Sansom Park. Just across the road from the popular Williams Ranch House steak and barbecue place was a signless lounge known as El Toga, an almost invisible beer joint physically hiding behind a mainstream beer joint.

Doorman Jerry “Big Mama” Cassidy, who would go on to become one of the most familiar faces in gay bardom, would then welcome you to a magical world where even the heady, forbidden thrills of drag performances or occasional live music couldn’t compare with the simple ecstasy of a few hours of just being yourself.

Dancing was encouraged as long as you quickly grabbed a partner of the opposite sex if Mama flashed the lights, alerting everyone that a police raid was imminent.

By the time the 651 pulled its inaugural beer in the winter of ’69, it may not have been the first place of its kind, but unlike so many bars that were to follow, it was there to stay. Of course, the original club looked very little like the crowded, warehouse-sized dancenasium most people remember from its heyday in the early 2000s.

One early patron described the 651 as a “bitty old hole in the wall that smelled like piss,” another as “a dark, dingy, ramshackle shitbox that always had a moldy, mildewy smell.” They were unanimous on an odor but also allowed that at least it was theirs. And for the majority of those early regulars at “The Six,” as it would come to be known colloquially, that was enough.

The quiet success of the 651 inspired other bars to open their doors as well. By the mid ’70s, as disco fever was beginning to infect clubs all over America, Cowtown had gay bars popping up all over the city, including the 500 Club on West Magnolia Avenue, The Come Along Inn just north of the 651 on Jennings (currently the 515 Club), The Other Place on Seventh Street, Bailey Street Wherehouse on Bailey Avenue in the Cultural District, The Regency on South Hemphill Street, and D.J.’s Bar & Restaurant, near Rosedale, the city’s first establishment that catered to lesbians.

Despite the spirit of cooperation among gay and lesbians today, the gender gap in those days was seemingly unbridgeable, almost into the ’90s. Female bargoers are still bitter about the 651 managers who deliberately left doors off the bathroom stalls in the ladies’ room to discourage women from visiting. D.J.’s, opened by longtime partners Darlene Smith and Josie Gallegos (“D” and “J,” get it?), was also the city’s first gay restaurant and became a launching pad for many a drag performer. Lesbians would finally receive the respect they deserved when they acted as caregivers during the coming plague. Again, I’m getting ahead of myself.

More success and visibility in the early ’70s also invited problems. Gay bars were usually located in decidedly sketchy parts of town, as even we perceived ourselves to be decidedly sketchy in those days. Many early partakers in Fort Worth’s lavender lounge scene recalled mostly being left alone. Others told of regular visits by cops who would barge in, randomly select three or four patrons, and arrest them for “public intoxication.” No one dared dispute the charge.

In 1974, when the inaugural Texas Gay Conference was held in Fort Worth, attracting a number of LGBT organizations from across the state, local police staked out the event and wrote down the license plate numbers of attendees, in some cases following them to gay nightclubs where more plates were taken down.

When Ken Cyr, director of the local group AURA (Awareness, Unity & Research Association), confronted police officials, he was dismissed and told it was standard procedure mostly done for their protection. Really? Was that the reason they also made those plate numbers available to media outlets? Which they did.

Thankfully, Cyr was undeterred and filed a civil suit the next year that included among the plaintiffs patrons of area gay bars, specifically the Bailey Street Wherehouse, the 500 Club, the Other Place, and, of course, the 651. They were the only of the seven or eight purported clubs in business at the time willing to step up for the cause.

By early 1978, the court had ordered that Fort Worth police destroy all records of license plates, names, and other personal data collected regarding area homosexuals. Cowtown gays had won their first victory in the fight against oppression, and the 651 and other clubs had proven they had their patrons’ backs when it mattered most.

With the 1980s came a surge in new clubs. Among the many that opened that decade were the Vickery Station, Across the Street, The Corral, Ashburn’s, The Copa, The Lumber Company, The Office, Sir Bud’s, Partners, and Twilight. In 1981, Fort Worth also held its first Gay Pride event, and eight years later, Pride hosted its first parade, with floats rolling down Jennings from Magnolia Avenue, right in front of the doors of the 651.

By late 1985 and ’86, the 651 had officially outgrown its digs. The bar owners had taken over the Laundromat next door years earlier, putting in pool tables and a dance floor for two-stepping to country music, which was a staple at the Six until the early 2000s. They also added a large patio in the back.

“They kept adding more crap to it every time you came ’til the damned thing was like a labyrinth,” recalls Jimmy Hutcheson, owner of Changes on East Lancaster Avenue. “But with its sagging ceilings and general disrepair, we always wondered how in the hell it could ever pass any inspection.”

There’s no telling what finally prompted the property’s owners to allow the bar to fully renovate. Some said it was a fire. Others surmise it might have been a partial collapse. That’s the most delightful part of pulling together a history of bars: Most of the people who were in the best position to remember anything were usually there drinking to forget.

A major renovation took place nonetheless, with much (but not all) of the old club torn down and a new, bigger one built in its place. During construction, most of the staff and bar regulars were welcomed at The Lumber Company (known as the “TLC”), which was across the street (hence its later name change to “Across the Street”). To make everyone feel welcome, Hutcheson remembers that little wooden table toppers appeared with the name “TL6” on them.

When the bar celebrated its grand reopening in a two-page ad in the 1987 Gay Pride Book, it was billed as “The New 651 Club, Fort Worth’s Oldest and Texas’ Newest.” Regulars immediately recognized the original bar and a thin faux wall between the bar and the dance floor, exactly where the original wall separated the lounge from the old Laundromat.

Amid the celebration and renewal, however, an even greater challenge was waiting to savage the community. On both coasts, a new disease dubbed GRID (gay-related immune deficiency) had begun spreading throughout communities of gay men in larger cities. More accurately renamed AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) in 1982, the disease didn’t make its way to Tarrant County until 1985, with 69 confirmed cases and 30 deaths by November of that year.

The newfound sense of pride and celebration had suddenly given way to fear and sorrow as the bars became unlikely hosts for memorials, where longtime familiar faces, community leaders, and popular performers were eulogized far too soon and too often. The Six was home to the playfully named W.A.D.S., or the Wednesday Afternoon Drinking Society, that, like so many other organizations, found itself repurposed to raise much-needed funds for AIDS charities.

In 1989, transsexual stage legend Rhonda Mae Cox, known simply as Rhonda Mae to friends and fans, began collecting money and canned goods for local food pantries beginning at The Office/Breakroom bars on Highway 377 on the city’s west side and eventually making its way through almost every other bar in town at some point, including the 651. Her efforts helped provide tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of food over the next few decades.

The arrival of the 1990s brought little good news for the community as AIDS cases began to skyrocket nationwide while viable treatment methods continued to elude exasperated doctors. The bars took on new roles as centers for fundraising and education in addition to escapism, and more venues opened their doors. Clubs like Cowgirls Oasis, Kings Cross, the Lancaster Beach Club, Crossroads Lounge, and Magnolia Station catered to a younger and increasingly more ethnically diverse clientele.

This, of course, is when things really started to get interesting, because that’s when I showed up – a terrified, newly out twentysomething newspaper writer who made his gay-bar debut on the opening night of Magnolia Station in October 1992.

As a newbie, the bar scene was fresh and frightening, especially whenever I dared to venture beyond the walls of Maggie’s (as we regulars had dubbed Magnolia Station back in the day). The first time I walked into the 651, the sight of cowboys two-stepping with one another was a shock to my still-delicate sensibilities. However, hanging out in a honky-tonk, even one where the boys in boots were into each other, still gave me flashbacks to a childhood spent in smoky beer joints scored by Tammy Wynette crooning about standing by her man or Kenny Rogers knowing when to hold ’em or to fold ’em.

No one was more shocked than I that less than a year later, in June 1993 at Magnolia Station, I would meet the man I would later marry in a state where I never dreamed marriage would be legal. Being partnered up hardly ended my tenure in bars, though.

By the mid ’90s, the dark cloud hovering over the gay community nationwide began to slowly break up as a new combination treatment known as the “AIDS Cocktail” emerged, offering real hope for people living with the disease.

In February 1997, the 651 celebrated its 28th anniversary by hosting a weeklong party and that spring, they opened a 3,500-square-foot patio with its own bar and barbecue area.

With the arrival of the new millennium came big changes. The Fort Worth gay community started to find its voice with the emergence of more gay organizations, churches, AIDS services organizations, and visibility than ever before.

More new bars arrived, including Best Friends Club, Changes, Club Konection, Neon Nights, and Vivid.

Then in 2005, for the first time in more than 35 years, the 651 closed its doors. It was reopened as Hot Shots under new managers and chugged along for a couple of years before the manager skipped town, leaving behind disappointed regulars and a lot of unpaid debt, according to several folks still miffed about getting stiffed. James Allen, owner of Stampede (formerly known as The Corral), tried to make a go of the place for a couple of months in 2006, reopening as The New 651, though reported disputes with the property owners prompted him to give it up. The 651 name would be no more.

In 2009, the building reopened for its final act as the Rainbow Lounge. The club welcomed record crowds, younger faces, and a new vitality that attracted gays and straights alike. Then just a little over a week after its opening, a group of perceptibly angry Fort Worth police officers and TABC agents marched into the bar on the night of the 40th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

Officers manhandled patrons, informed them they were under arrest for public intoxication (shades of transgressions past), placed them in zip ties, and perp-marched them out the front door to waiting paddy wagons. One young man was thrown to the ground so roughly, he was later sent to the hospital with a head injury and bleeding on the brain.

Was the irony of the night chosen to carry out this debacle lost on the officers? Almost definitely. The irony was not lost on me or a number of my friends in attendance that night. It was my 43rd birthday. (I still didn’t look a day over 31. Ask anyone.)

Shocked and angered by what we saw, we gathered at my place after skulking away from the bar in stunned disbelief. We immediately took to the socials, and our early-morning efforts helped the story make national headlines by daybreak. A protest on the steps of the Tarrant County Courthouse the next day attracted hundreds, followed by many more protests, meetings, candlelight vigils, the birth of a new activist organization called Fairness Fort Worth, and the start of a new era of change and improvement in the lives of local LGBT people.

So many good things came from such a truly awful evening: changes to the city’s anti-discrimination policies; diversity training for all city officials, including police and fire; a place at the table with the clout to make a real difference for our community. We had contacted Dallas filmmaker Robert Camina, who began filming the next morning what would eventually become a documentary about that evening. Watching Raid of the Rainbow Lounge today still effectively taps into the raw emotions we all felt after that experience.

The reverberations of that night extended far beyond North Texas and were felt across the country as other city officials reached out for advice on making change in their own communities.

The newfound fame of the Rainbow Lounge led to more growth for the business, augmented by the opening of a new bar down the street, Percussions; a gay-owned restaurant next door, Randy Beez; and the purchase by Rainbow’s owners of Best Friends on East Lancaster. Healthy crowds also led to the opening of another club, Reflection, across the street, capturing Fort Worth’s closest attempt to successfully creating its own “gaybourhood.”

Unfortunately, the attention came at a cost. Many of the biggest voices behind the improvements were burned by the spotlight and began to step back, some moving to Dallas, others retiring or simply walking away. Tom Anable, a vocal and tireless spokesman for post-raid change and one of the movement’s most charismatic leaders, took his own life while his work as president of Fairness Fort Worth was at its busiest.

Tom’s suicide was shattering, and while the work continued and the bars flourished, for many of us, his memorial at Rainbow Lounge was a sign that the time had arrived to leave the bars to the next generation.

Kyle and I used to argue about the relevance of gay bars and whether they were even necessary anymore. I postulated that as long as the coming-out process was painful and frightening to people, regardless of their age, the necessity of places you could escape to and feel accepted and safe would always be necessary. He countered that today’s LGBT youth feel comfortable in almost any bar in Fort Worth. Our debates on the subject, usually held at the front corner of the main bar at Rainbow, the exact spot we’d met years earlier, would often appear to bystanders as if we were about to come to blows. That’s just how we talked.

I’m not admitting that he’s right, mind you, but hell, I spend most of my nights out at the Chat Room Pub on Magnolia, a gay-friendly – well, everyone-friendly neighborhood bar that sure feels like home to me. Perhaps the gay community’s long battle for acceptance was too successful. Gay bars around the country are shutting their doors for good, some with legacies older than Rainbow’s/651’s nearly 50 years.

I look around this invisible graveyard of secret lounges long gone and can’t help but wonder what they must have been like. Many sites have been torn down. Others have left behind architectural hints of former glory. Still others have taken on unlikely new lives – the old home of El Toga is now an Ace Hardware, Bailey Street Wherehouse’s location is home to the Junior League of Fort Worth, and Magnolia Station, where I met the man I get to spend many more years with thanks to modern medicine, is now the Mother’s Milk Bank of North Texas.

When the ashes of Rainbow Lounge are bulldozed and replaced with high-priced apartments most likely – it’s what happened to its former sister bar, Percussions, just up the street – who will remember what came before?

A conversation with one of the current Rainbow owners, Tom McAvoy, confirmed that the Rainbow Lounge will rise from the ashes in a new, yet-unnamed location as soon as Sept. 1.

“We had to rebuild that bar, not for us, but for the community,” he told me. “We just didn’t want it to die.”

There’s still no denying that a piece of gay history perished in the flames early that June morning. And when LGBT patrons and the people who love them step into a new Rainbow Lounge later this year, or wherever they feel comfortable being themselves in a world that’s not nearly as intimidating or dangerous as the one in which the original 651 opened its doors, maybe those decades of police intimidation, violence, stale cigarettes, mildew, hangovers, zip ties, and the ghosts of so, so many amazing people can rest in peace.

Finally.

Co-founder of QCinema (Fort Worth’s Gay and Lesbian International Film Festival) and Fairness Fort Worth, Todd Camp is a recovering former Star-Telegram writer currently working on a book about Chase Court, his nearly 130-year-old neighborhood on the city’s Near Southside, as well as a project about the history of Fort Worth’s gay nightlife. You can reach him at todd@qcinema.org.

I will admit that this article left me a little misty-eyed. I came out late in life and met my husband at Hot Shots (nee 651, after, the Rainbow Lounge). Reading this, I can hear the music, smell the stale cigarette smoke, and feel the laughter and joy of being somewhere that I could be COMPLETELY myself. And that’s the whole point of the thing, isn’t it? My friend Todd Camp is brilliant and he is our memory.

Thank you so much, sweet man! I’ll always be grateful for Magnolia Station bringing you into my life.

This was a great article. As an out bi woman, I often wondered where Ft Worth’s gayborhood is. I live in Arlington but go to Sue Ellen’s in Dallas as well as some of the wine bars on Oak Lawn. Someone told me that Ft Worth was more diverse and accepting, so the need for the neighborhood never really existed. Is that true? … or, do I need to get out more?

Hey Beth, I guess the answer depends on your perspective. The closest thing Cowtown has to a “gayborhood” at the moment is the South Jennings Avenue/Pennsylvania intersection, which is now home to two bars (Reflection and 515 Club, and formerly Rainbow Lounge). There are also two clubs on the east side near Lancaster and Beach, The Urban Cowboy Saloon and Changes). The truth is, you can go out to almost any bar on any given night and find LGBT people, it all depends on your comfort and confidence level. But apart from a short window where South Jennings was home to four bars and gay-owned restaurant, the notion of a centralized gayborhood was never fully realized. I always encourage folks to patronize gay-owned businesses whenever you can in the hopes that they may flourish. Best of luck!

So many memories come back looking at this. Miss you Todd

Miss you, too, buddy.

Thanks Todd, didn’t know the history behind 651 club. The first bar u bese worked at. It will be miss. An empty space in my heart. Alot of good thoughts go to that bar. It was a true icon to alot of people.

Good riddance. Maybe the fire cleanses some of the pathogens from the place.

Hi Todd, regarding the “OP”, Other Place, I don’t recall it being on 7th st, but around 1979 or 80, it was located first on Jacksboro Hwy, near University Dr, next to what I vaguely remember was a old hub cap business. The OP was small but with a outside patio.

I was just out of high school when, as I entered my first gay bar when legal drinking age was still 18, Mama welcomed this nervous young man. Many good times, indeed, followed at that location until around 1982 they moved to a warehouse off White Settlement road, not far from Angelos BBQ. The new location was bigger with a ‘quiet’ bar, a booming dance floor, and about a year later a restaurant in the back. Mama was always there and I got to know the owner TJ, who like that the Other Place was popular among younger new wave and preppy types alike. By then I was going to TCU and the OP became quite a festive place for about 2 more years, until eventually the crowds began to thin out to the point it closed altogether.

By that time around mid 80’s Vickery Station had opened and for a few years more and became the place to dance, in fact I remember one super fun night dancing while Helen Reddy actually performed live !

While I did venture to Jennings area a few times where there was 651 and Corral, and one other bar on the corner and across the street which I can’t recall the name, however the crowd was mostly cowboy or older types and because none of them were known for good dance music. By the end of the 80’s I moved out of state and didn’t get to enjoy the times that surely followed in the later years.

I’m do have many good memories of these Ft W bars and a several others during the 80’s.

Hey Pete, thanks so much for your response. I’m sorry for the delayed reply. I’ve had a personal tragedy that took me out of commission, but I’m eager to talk with you about some of the memories you have regarding the local nightlife scene. Please feel free to reach out to me at todd@qcinema.org and I’ll share some information about an upcoming event to collect stories about the place. Look forward to talking with you!

Hi Todd, thanks for this good article and historical references.

I lived in Ft W during the 80’s and spent many a good nights at a few of the places mentioned. Around 1980 when the Other Place was located just past University on Jacksboro Hwy – back when drinking age was still 18 – the OP was my first visit to a gay bar just after my senior year in high school when “Mama” greeted me at the door and make me feel at ease.

A couple of years later the owner TJ moved the OP off White Settlement road in an old warehouse near Angelo’s BBQ, and for about 2 years the OP was the place to go dancing during my TCU years and it was always packed until the Vickery Station opened around mid-decade. Mama was still greeting customers which by then attracted new wavers & preppy types both gay and straight during these festive hey days. Both OP and Vickery played good 80’s dance music though eventually OP lost their crowds and they opened a restaurant in the section past the dance floor but it did not do well.

When the Vickery Station became popular around ’86 one especially memorable night Helen Reddy performed live to a packed dance floor to a mixed crowd of gay and straight having a blast. A few times we stopped by the 651 and the other 2 bars nearby (the Corral on Cannon and Hemphill and the other one directly caddy corner on Jennings and Cannon) though sparse crowd seemed subdued to those seeking a more festive atmosphere. Overall by the end of the decade there seemed to be a lack of good music and dance bars in Ft W.

Though I moved out of state and still visit occasionally, I’ve heard Rainbow is planning a reopening near the old Vickery Station in late summer so here’s hoping that good sparks might fly once again.

Thank you, Todd, for a beautiful review of the bars in my home town! We’ve been away from TX since 2002, but we will always remember the Friday evenings I spent two-stepping with the most beautiful girl in the world and the role that played in her eventually becoming my wife. We were blessed to share a tiny slice of that history.

Is there any place a bi curious man can go to meet people that isnt a bar??

I remember Aub’s, which was a steakhouse and drag bar. It was owned by a man named Aub. Josie and Darlene ran it. They bought him out around 1980, and it became D.J.s. straight older couples from the area sometimes dined and stayed for the shows. I started going there in 1976 when I was 18 and could legally drink. Still Facebook friends with Jamie Fox. Pretty much all the others have passed away.

Wonderful and memorable events have come to mind. Thank you for posting all the events that have happened leading up to today’s gay world. Much luck with you articles. Thanks again for all the research that you have done because as I read this article, I know you are much too young to have lived through it all, unlike myself and so many people I know. Great memories come back and sad memories but all good memories that have lead to where, we as a gay society have reached at this day and time. I look forward to you continued writing, best of luck in the future.

As Bob Hope would always say, THANKS FOR THE MEMORIES. You can’t have good memories without wither bad. All memories are good because we are still alive and so many of my friends and so many people that I knew of are not around to remember. Thanks again. Look forward to future articles.

One place I notice you did not mention in Fort Worth was, THE TENDER TRAP, located at the corner of East Lancaster and Riverside Dr. it was a sleazy little bar that not only would gay people visit, they had a older crowd of hard working men that would frequent the bar after work. Everyone seemed to get along but I and my first partner at the time only went there to rendezvous there then go out to dinner. It ni linger is in existence but I though you might like to add it to your list of gay bars in the 80’s that was in Fort Worth.