In his nicotine-addled, sleep-deprived state, his real life and his fantasies start to blur, and the various women in his life – including his wife (Marion Cotillard), mistress (Penélope Cruz), lead actress (Nicole Kidman), longtime costume designer (Judi Dench), a fashion reporter who wants to sleep with him (Kate Hudson), and even his deceased mother (Sophia Loren) – appear to him in hallucinatory musical numbers. Since the numbers are the fantasies of a controlling egomaniac, many of the songs have the women singing Guido’s name repeatedly.

The film is directed by Rob Marshall, who brought Chicago to the screen. Marshall’s background is in theater, and he’s still figuring out the possibilities of the cinematic medium. Fellini is an obvious source for references, as some of the sequences here are shot-for-shot replicas of sequences from 8½. Composer Andrea Guerra does his best impression of Nino Rota, and Kidman is made up to look like Anita Ekberg.

The numbers remain mostly stagebound despite Marshall’s efforts to give each one its own character. He shows improvement from Chicago when it comes to integrating the numbers into the setting: “Cinema Italiano” is shot like a fashion show, with Hudson dancing on a runway with a bunch of male models. Marshall choreographs the dance numbers along with John DeLuca, and they do an innovative job of staging “Be Italian,” with dancers holding tambourines and kicking up sand. Marshall directs with a great deal of energy and flair as usual, yet he never finds a way to build momentum within the numbers (the score doesn’t help him), which is why none of them really soars.

Fortunately, he’s chosen his performers well, and they often ride to the rescue. Day-Lewis is a natural fit for the tormented Guido, and his raw nervous energy is bracing in these plush surroundings. His two songs (“Guido’s Song” and “I Can’t Make This Movie”) don’t make extensive musical demands on him – they’re basically angst-ridden dramatic monologues that can be half-spoken – and he works himself into a nice lather with them. No dancer, he nevertheless gets to clamber around on scaffolding during “Guido’s Song,” reminding us how well he moves. This is the best showcase for Day-Lewis’ physical skills since The Last of the Mohicans.

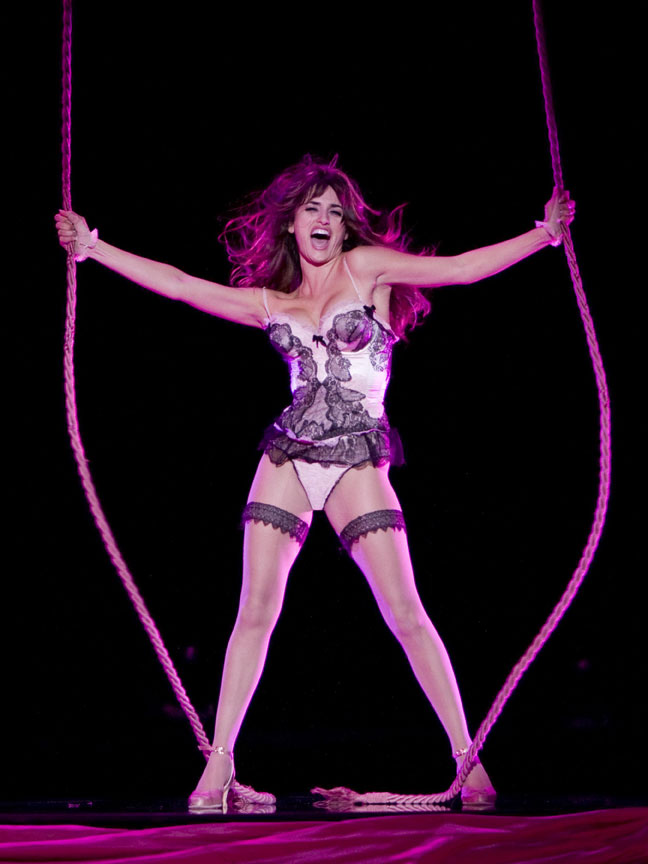

Day-Lewis notwithstanding, this show belongs to the women around him, and Marshall trots them all out in the opening number, “Overture delle Donne.” (When your movie has this much star power, why be shy about it?) The best singing comes from Black Eyed Peas lead singer Fergie as Saraghina, the coarse seaside prostitute who gives young Guido his first taste of sex. Fergie not only looks like she stepped out of a Fellini film but also drops the Black Eyed Peas stylings as she sings “Be Italian” in the Broadway style. Cruz dances around with ropes while wearing a bustier in her number, “A Call From the Vatican,” and for those few minutes you can’t look anywhere else. She burns up the screen, yet the acting honors are stolen away by Cotillard as Guido’s former leading lady, now reduced to being his cheated-on stay-at-home wife. The dramatic high point here is when she sings “My Husband Makes Movies,” a piercing, clear-eyed account of what it’s cost her to live with this unfaithful, self-absorbed genius. The Oscar-winning Cotillard delivers her greatest performance to date here.

If the film feels less than the sum of its parts, that’s probably because of Maury Yeston’s songs, which are mostly from the Broadway show, though “Cinema Italiano” and “Take It All” are new. None of them are terribly inspired musically, the lyrics are riddled with clichés (“Be a singer! Be a lover! / Pick the flower now before the chance is past”), and at least two songs (“Cinema Italiano” and Dench’s number, “Folies Bergère”) are pure filler, failing to advance the plot or reveal character. This musical ends quietly instead of with a conventional high-energy, showstopping finale. The gambit doesn’t pay off, as courageous as it is.

In the end, the performances and the intelligent script by Michael Tolkin and the late Anthony Minghella (Marshall does pick strong scriptwriters) prove to be enough to buoy this film. Nine isn’t the musical equivalent of Fellini’s masterpiece, but it’s a nice piece of holiday entertainment. More than that, it’s as good a movie and maybe even a better one than the Broadway show deserved.