Bullets sliced into Tim and Becky Morton’s east Fort Worth home after a drive-by shooting in 2009. It was a terrifyingly close call — police dug bullets from the walls in the children’s room afterward. No arrest was ever made.

The Mortons have long enjoyed living on the East Side. Tim is past president of the East Fort Worth Business Association, and he and Becky own and operate a pet clinic near I-30 and East Loop 820. Tim is also a business law attorney. He figures a courtroom clash might have angered somebody with a violent streak.

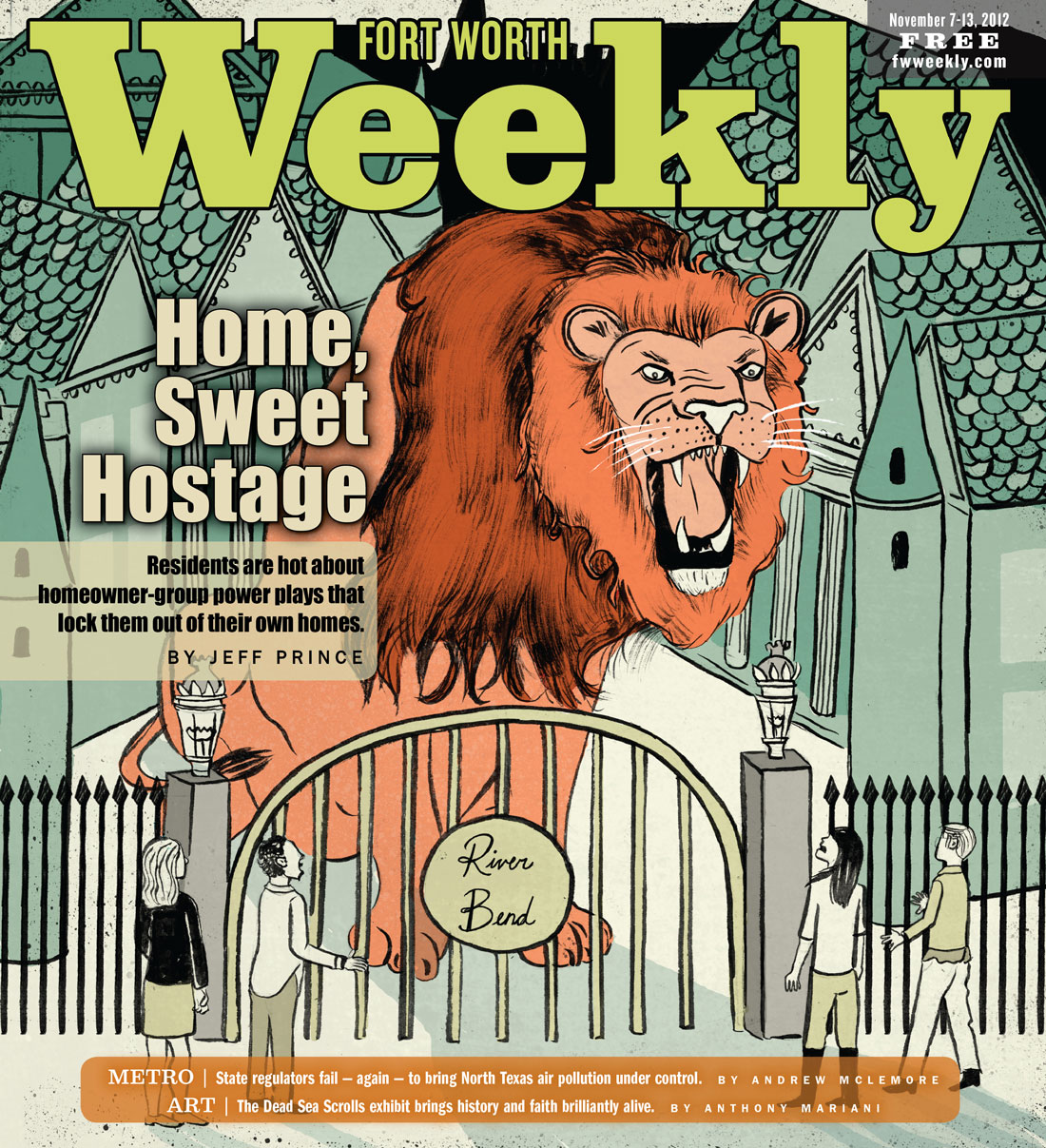

After the shooting, looking for more security, the couple and their two kids moved to a gated community on Randol Mill Road near East Loop 820 in the Woodhaven area. Their 3,500-square-foot home in the exclusive RiverBend Estates felt like a warm glove. A long, winding, masonry fence with sculpted bas-relief panels surrounds the 200-acre neighborhood. Canals, fountains, big trees, a private lake, ornate streetlights, and a 24-7 guard at a gated entrance provide a cozy backdrop to the homes that range in price from several hundred thousand to several million dollars.

And yet the Mortons soon felt threatened again. The new attack didn’t involve bullets. None were needed. Homeowner associations use fines, liens, and lawyers.

“A lot of homeowners associations have strict rules, and that’s why a lot of people are attracted to them,” RiverBend attorney Joe Tolbert said. “City ordinances fall short for many homeowners. They want more stringent ordinances, and they choose to move into [gated] subdivisions that have more restrictions than city ordinances require.”

Homeowner-elected board members are “just volunteers doing the best they can,” he said.

It can be a thankless job. Board members become de facto referees when two neighbors cross swords and can’t work out their own problems.

On the other hand, power can corrupt. Piss off the wrong board member, and you might face a stacked deck. Rules can be creatively interpreted. The board has the final say (short of a lawsuit). Boards use membership dues to fund their legal battles. Residents who take on these groups are, in effect, financing both sides. RiverBend’s 200-plus homeowners pay $150 a month for dues for an estimated $360,000 a year. Some residents have complained about legal expenses from recent court battles that have approached $100,000.

Meanwhile, RiverBend is using a controversial weapon — lockouts — to fight their own residents. The board tells gate attendants to refuse entrance to family members and friends trying to visit residents at odds with the homeowners association. According to rules at RiverBend, the board can refuse to allow residents or their guests to use common areas if a resident doesn’t pay dues, fines, or penalties on time. But common areas in homeowners associations are typically considered amenities such as swimming pools, picnic areas, and golf courses, but not streets. A legal precedent has yet to be established.

“It is so bad; I don’t want you to think I’m spinning you a tall tale,” Tim Morton said as he began to explain how his family’s alleged infraction of a RiverBend rule led to months of debate, letter exchanges, lawsuits, and spiraling legal costs. The Mortons eventually listed their house for sale and moved. They found no buyers, so they took the house off the market and leased it to a tenant.

“We think RiverBend is unique in how bad and egregious they are, but it’s a problem all over Texas,” Morton said. “[Homeowner associations] can do anything they want until somebody stops them.”

Restrictive covenants, or deed restrictions, were used to establish racially segregated neighborhoods during much of the 20th century. Fair-housing laws curbed the practice in the latter part of the century. These days, homeowners associations use strict covenants to limit certain types of architecture and to ensure that residents maintain their houses, lawns, and vehicles.

Over the years, residents across the country have complained of homeowners association boards that meet in secret, maintain shoddy records, and have access to large amounts of money with lax oversight. Headlines have reported many cases of fraud and embezzlement.

Regulation typically has been spotty in Texas. Homebuilders who establish controlled-access subdivisions have contributed many millions of dollars to political candidates to prevent or stymie reform efforts in the past decade. However, the 2011 Texas Legislature initiated laws that require open meetings, give resident access to records, limit non-judicial foreclosures on property, and give residents more time to pay off debts to their associations.

Not everyone’s happy. There remains relatively little oversight of boards. The occasional power-mad board members can run amok, penalize residents whether the rules allow it or not, pile on additional penalties, and file liens on homes. Don’t like it? See you in court — on your dime.

“The laws are in favor of the homeowners association industry,” said Beanie Adolph, reform project director at Texas Housing Justice League, a group formed to address abusive rules, improper eminent domain efforts, and other housing problems.

Still, she and most others agree the laws are a step in the right direction to provide residents with protections when covenants are wielded like battering rams.

********

An estimated 5 million Texans live in 30,000 neighborhoods governed by homeowners associations these days. That’s about one Texan in six. (Figuring out the exact numbers is difficult due to the lack of regulation.) The concept taps into a survivalist mentality that stretches back through the ages. Like-minded people want to live near one another, establish rules to protect the whole, and share the responsibility for common areas and amenities such as swimming pools, gyms, and clubhouses. The bottom line, for many, is the bottom line: keeping property values high.

They want beefed-up deed restrictions, rules on property use and appearance, and enforcement. Real estate developers seeing the demand establish homeowners associations as a selling point. Many surround their developments with large fences to define their boundaries.

Fail to mow your lawn — you’re fined up to $250 a day. Speed through the neighborhood — fined. Car on blocks, noisy dog, grass growing through cracks in the driveway, wrong paint color, whatever — fined. Don’t pay, you’re fined some more. Still don’t pay, and the board can put a lien on your house. Dig in your heels further, and the board can foreclose on your home to force payment of past dues, fines, and attorney fees that can quickly grow into the thousands of dollars. Still don’t pay, and you can lose your home on the courthouse steps.

It might sound heavy-handed, but people pay dearly for that supervision. An estimated one of four homes built in Texas during the past decade was in a neighborhood with a homeowners association. Monthly dues create a pool of money to pay for security staff, landscaping in common areas, amenities such as swimming pools and golf courses, and street construction (streets inside gated communities are often maintained by associations rather than their cities). RiverBend’s approximately $30,000 a month covers security, landscaping, lake maintenance, and streets. There is no public pool or golf course.

That money can also pay for attorneys.

The Mortons welcomed the deed restrictions and protections when they arrived. The neighborhood was serene. Yards were tidy. The Morton home was just a few years old, comfortable and pretty, with a three-car garage and large driveway. The county appraised its value at $300,000. Life was good.

“Since HOAs are very local and small, participants are often neighbors and hence have incentive to settle disagreements in a civil manner.”

– “Free Market Alternatives To Zoning”

The Independence Institute (Denver, Colorado)

February 28, 2009

http://old.i2i.org/main/article.php?article_id=1702

This story seems one sided. The author lost credibility with the personal attack of the HOA President. Why bring the man’s company, charitable works and religious beliefs into this? Seems the disgruntled homeowners are using this to settle a personal vendetta against the HOA President.

If you had even read the article, personal attacks are absolutely appropriate. This especially pertains to tort, such as in this case. Learn to think…

I find it hard to believe that this HOA President made all of these choices by himself. The entire board would have to vote and approve each rule and enforcement. You failed to mention that a local Judge sits on that board or the name of the big law firm the lawyer works for….but you had no problem attacking a local businessman, his religion and his character. I thought the FW Weekly was above this type of Journalism?

“I thought FW Weekly was above this type of journalism” Oh Dear, I guess you missed the one sided hatchet job FWW did on the FW church on I-35 around Labor Day.

“WE BUILD THE PRISONS WE LIVE IN.” Red Desert Penitentiary

Looks like you got yourself some republican resistance here, Jeff.

A hack story produced by a hack “journalist,” published by a hack rag. Poorly written, error-prone, rambling, and with a decidedly one-sided agenda.