You might find it unsettling if a cop pulled you over for speeding and said, “May I see your driver’s license and registration, and may we go to your house so I can snoop around in your bathroom medicine cabinet and see which pharmaceutical medicines your doctor has prescribed to you?”

Police officers don’t need permission to peek into to your medicine cabinet. Texas law allows cops to access an online database that contains everyone’s prescription medicine history. The law has been on the books since 1983.

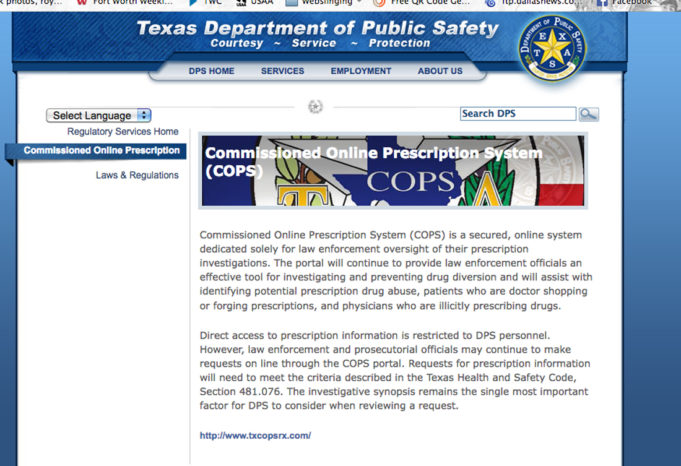

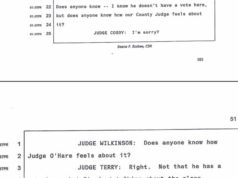

A local attorney called the Weekly office recently to express dismay about the Commissioned Online Prescription System (COPS), a database available to police officers investigating cases of prescription abuse and fraud. David Sloane, a former cop turned lawyer in 1996, said he is representing a client who had his prescription history tapped into by a cop investigating an unrelated case. Sloane had never heard of the database.

“This is the first time I’ve seen it,” Sloane said. “I was shocked. I talked to several other lawyers, and they were shocked.”

So what’s the big deal about a cop seeing someone’s prescription history? If you don’t have anything to hide, why worry?

Well, there’s a little thing called privacy. If a cop looks at your prescription history and sees that you are taking medicine for AIDS, mental illness, testosterone, herpes, depression, pain, or any number of things, the officer might make judgments about you, Sloane said.

“You can determine a lot about somebody by looking at their medicine chest,” he added. “It violates a person’s privacy. Medical records are supposed to be private.”

Law enforcement agencies are typically required to get a subpoena when searching or accessing someone’s private information or property in a criminal investigation. Supposedly, the Texas Department of Public Safety releases information from the online database only to cops who are investigating prescription drug cases that meet the criteria spelled out in the Texas Health and Safety Code. The criteria includes a vague statement that the database director can release info if “proper need has been shown to the director.”

That makes it sound like the director can release info whenever he wishes and to whomever he wants. We called the COPS director to find out how many requests for info are submitted each year, and how many times the director releases the info. But the director told us to call another guy, who told us to submit our questions in writing so that he could forward them to another guy. We submitted the questions on February 3. We’re still waiting for answers. We doubt cops have to wait two weeks to get a response when they want to know whether you are popping Xanax for breakfast.

Before you head to Austin to protest this assault on personal privacy, keep in mind that nearly every state in the country has a program almost identical to COPS. And DPS isn’t the only one overseeing the data. In September, additional oversight was given to the Texas State Board of Pharmacy. Gay Dodson, the agency’s executive director, said the goal is to promote, preserve, and protect public health and safety.

“It is a really good clinical tool for physicians, prescribers, and dispensers to be able to make a better judgment on whether this prescription should be dispensed or not,” he said.

Info is released only in certain situations, he said. If a police officer asks for someone’s prescription history, DPS should monitor the requests so that “it is not a witch hunt” and if “there is a real reason to do it,” Dodson said, adding that he is not aware of any cases when the system has been abused by police.

“I think I would have heard about it,” he said.

That’s nice. Still, we would like for DPS to answer our questions.