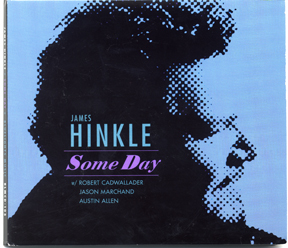

Maybe it’s not a ringing endorsement in the steely eyes of blues enthusiasts, but bluesman James “Gut-tar” Hinkle’s new album, Some Day, has crossover appeal. For non-blues lovers, people whose idea of burning in hell involves being trapped in a smoky dive surrounded by the over-40 set and being regaled by white-boy blues, the Fort Worthian’s collection of 13 originals might be far from offensive.

Along with longtime collaborator and veteran pianist Robert Cadwallader, Hinkle is backed here by the barely-old-enough-to-drink-legally rhythm section of drummer Austin Allen and bassist Jason Marchand, both Baton Rouge natives swept into North Texas by Hurricane Katrina. Shuffle, waltz, rock, stomp, march, jumping up and down and waving their hands – you name it, Allen, Marchand, and Cadwallader can do it.

So can Hinkle, whose ax contains a half-century’s worth of American music. Former slinger for hell-raising pianist and singer-songwriter Marcia Ball and bluesman Johnny Mack, among many others, Hinkle grew up here and in Austin happily trapped in smoky dive bars surrounded by the over-40 set and being regaled by — not blues-rock (thank goodness) — just the blues, purveyed by legends such as U.P. Wilson, Fort Worth’s Robert Ealey and the Bruton brothers, Buddy Guy, and “Pinetop” Perkins. Though Hinkle’s last album, Blues Now, Jazz Later, had a lot going on guitar-wise, Some Day seems to have stretched his repertoire even further and not directly because of the rock and funk brought by the youthful duo of Allen and Marchand – Hinkle’s been there, done that. No, as the young’uns, with Cadwallader at their back, push the album toward rocking, funking, and decidedly non-bluesy terrain, Hinkle reaches even deeper into the unadorned past, retrieving handfuls of bluegrass and folk, which results in a surprisingly welcome contemporary-vintage fusion. Or maybe he just wanted to say, “You boys are hot, but school’s now in session.”

So can Hinkle, whose ax contains a half-century’s worth of American music. Former slinger for hell-raising pianist and singer-songwriter Marcia Ball and bluesman Johnny Mack, among many others, Hinkle grew up here and in Austin happily trapped in smoky dive bars surrounded by the over-40 set and being regaled by — not blues-rock (thank goodness) — just the blues, purveyed by legends such as U.P. Wilson, Fort Worth’s Robert Ealey and the Bruton brothers, Buddy Guy, and “Pinetop” Perkins. Though Hinkle’s last album, Blues Now, Jazz Later, had a lot going on guitar-wise, Some Day seems to have stretched his repertoire even further and not directly because of the rock and funk brought by the youthful duo of Allen and Marchand – Hinkle’s been there, done that. No, as the young’uns, with Cadwallader at their back, push the album toward rocking, funking, and decidedly non-bluesy terrain, Hinkle reaches even deeper into the unadorned past, retrieving handfuls of bluegrass and folk, which results in a surprisingly welcome contemporary-vintage fusion. Or maybe he just wanted to say, “You boys are hot, but school’s now in session.”

Actually, one of the album’s most lustrous tracks is a bluegrass-y solo-acoustic instrumental, “Three-Legged Alligator,” a soundtrack of sorts to a-goin’ fishin’ on a blindingly sunny day. “I Have No Idea,” another instrumental but one in which Hinkle is accompanied by Cadwallader’s 88’s, is equally fantastic. Over a simple rollicking riff, the piano and guitar bounce along hand in hand. The scratchy, tinny timbre of Hinkle’s plucking and sliding licks might have been achieved by recording them in an empty malt liquor can.

Hinkle is a master of subtlety. The leadoff track, “Ball and Chain,” could have been just another Stevie Ray Vaughan rave-up if not for the individually plucked guitar notes that echo during the verses, each one a split-second behind the beat but, as the old saying goes, right on time. Though bombastic, the song, as you can imagine, is very intimate – a fan might wonder if all of that tasteful restraint will resonate onstage or even be performed live at all.

Another track that breathes down your neck as intensely as any Radiohead studio ballad, “Some Day” boils down to a tambourine and bright, tiny riffage to whose calls Cadwallader’s piano responds sympathetically. “Fall of a Lifetime” lets Hinkle twirl his strings like a Delta-born Mark Knopfler and also give a strong, sincere vocal performance. That mischievous, smoky, Loozianin drawl that he sometimes trots out to excite some of his hopping numbers is shelved for North Texan simplicity, because it’s what the song needs.

Produced by Lost Country’s Jim Colegrove, Some Day, though, is far from headphones-listening music. An earsplitting false crescendo kicks off one of a couple of songs that could be Steely Dan classics. “I Know What You’re Looking For” has a snappy beat and a vocal melody that glides along, stops, bunches up, and gets gliding again. In between, Hinkle and his guitar channel Larry Carlton, playing effervescent, supremely elegant tones that meld jazz and blues and that would qualify as elevator music in any other context, a testament to Hinkle and company’s hep-cat edge.

The other Steely Dan-ish number, “Got Some Making Up to Do,” emulates Donald Fagen and Walter Brecker at their most bluesy and Gaucho-ish. With Cadwallader’s organ buzzing dramatically in the background, Hinkle and company float around the crackling beat, sneaking up on it here, confronting it there. The main riff finds Hinkle calling and responding with himself, chopping at a chord, then adding a little solo touch, then chopping at the chord again, then adding another little solo touch, a combination that moves the song along, building a melodious rhythm that’s not just kind of smooove but is straight out of George Benson’s bag o’ tricks.

Lyrically, Hinkle hews to tradition, contemplating love, loss, and loves lost in a variety of witty turns of phrase. The most barroom blues-y song, “Bitch on Wheels,” is a statement that won’t bend for any quick and easy rhymes: “We used to go together / Like red beans and rice / And you say I’m laid back / But I ain’t layin’ down … You prove you’re a bitch on wheels, honey / Ah, but I’m drivin’ the car.”

The sonic expansiveness here isn’t just limited to jazz- or blues-rock. The countrified Allman Brothers pop up here and there, there are a few crunchy ZZ Top flourishes in effect, and one song, “Mardi Gras Girl” – “Doin’ her thang for a handful of beads” – is about as close to zydeco as a non-zydeco song can be.

Blues music for blues haters? Don’t say we said it, but we did.