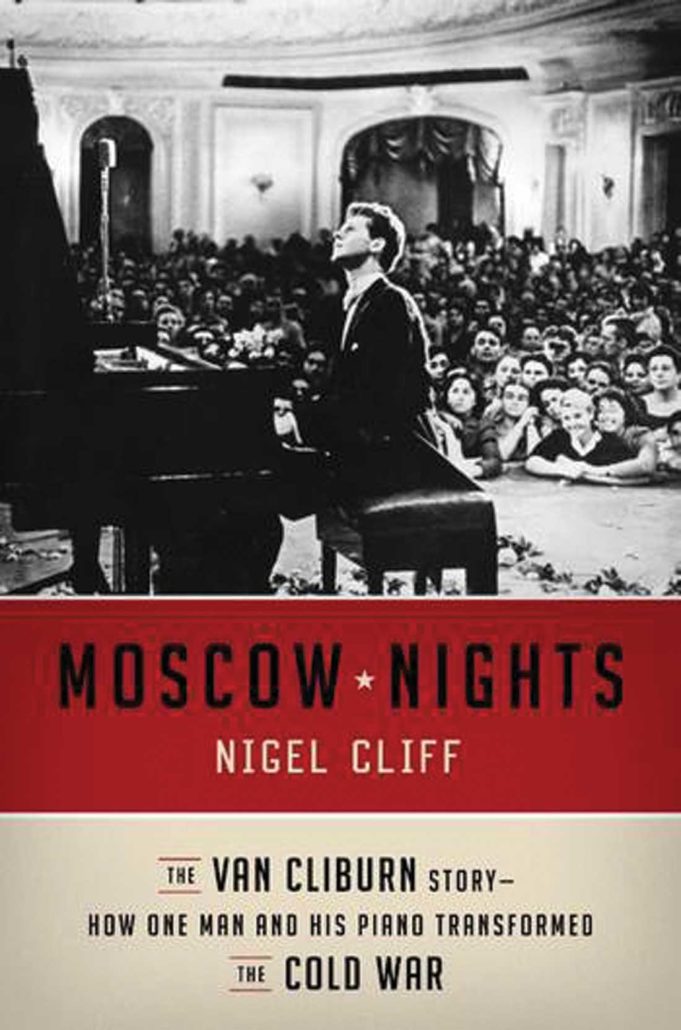

Author Nigel Cliff (The Shakespeare Riots, The Last Crusade: The Epic Voyages of Vasco da Gama) is on well-trod ground here. More than a handful of biographies of Van Cliburn have come out over the past few years, even before the legendary Fort Worth pianist’s 2013 death at the age of 78. Howard Reich’s The Van Cliburn Story from 2008 was optioned for a feature film last year. Early next year, Stuart Isacoff will release When the World Stopped to Listen: Van Cliburn’s Cold War Triumph and Its Aftermath.

Rather than rehash Cliburn’s life, Cliff focuses on the years surrounding the first International Tchaikovsky Competition, the historic moment when a young man from West Texas won the hearts of the Russian people and changed the course of world history.

The book flows chronologically, albeit with divergent paths at times that may leave the reader lost in a sea of obscure references to New York City-based Russian bathhouses or renderings of histrionic conversations between Tchaikovsky and pianist Anton Rubinstein. Appearing in the opening chapter, “Prelude in Two Parts,” the dialogue acts as a reminder that Cliburn’s 1958 victory in Moscow was possible only because of very real Russian influence. Russian composers, conductors, and pianists began reaching American shores around the turn of the 20th century, leaving an indelible impression on the New World’s audiences.

Cliff doesn’t stray far off course. The second chapter, “The Prodigy,” succinctly sums up Cliburn’s childhood while peppering the retellings with images of life in Kilgore, Texas. Music and religion were the “twin themes” of Cliburn’s childhood, Cliff writes.

Easily the most entertaining chapter, “The Successor,” follows soon after. The date is March 1, 1953, and Soviet Union leader Josef Stalin is in the throes of death. It’s clear that Stalin’s comrades, including then-Deputy Premier Nikita Khrushchev and former foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov (namesake of the Molotov cocktail), are eager to be rid of the tyrant. But unsure of his demise, they dutifully call in a doctor. Dark humor ensues. As Stalin’s pulse halts, a medic begins to pound on the dying dictator’s chest.

“Please stop that,” Khrushchev says. “What do you want, to bring him back to life?”

The bulk of the biography’s pages are saved for the days leading up to, the days during, and the ones immediately following the Tchaikovsky competition. Cliff lays out the historical tidbits in a tapestry of lively prose that infuses life into the characters, most of whom are now long dead. Among the personalities in Moscow at the time, Paul Moor, a journalist from El Paso who studied at Juilliard, was a welcome reminder of home to the young piano competitor while Premier Khrushchev is described comically as he jumps to kiss Cliburn’s cheeks. In later conversations with Cliburn, the Soviet premier can’t recall in which month his son was born.

As Cliff writes in the final chapters, the tall, lanky virtuoso was largely unprepared for the sensational response from the media and public upon his return. A Time magazine cover story surprised Cliburn and his family with scandalous depictions of his family’s financial problems (largely overblown) and hints that the shy pianist was “queer.”

Moscow Nights is not as much a story about Cliburn as it is one of his family, friends, and the events that lay on the periphery of the pianist’s life while he was alive. For Fort Worthians curious about his later years in North Texas, this book doesn’t offer much. Cliff only hints at that time. As an account of the political climate and cultural events that the genius musician found himself in as a young man, Moscow Nights may long stand as an enthralling resource for historians, audiophiles, and the general public alike.

Moscow Nights,

by Nigel Cliff

HarperCollins Publishers

452 pps.

$28.99