We’re talking genuine sublimity here, art by three bravehearts and current college profs who’ve obviously developed their distinct voices sketch by painstaking sketch, year by painstaking year. Wood’s signature style involves amoeba shapes in charcoal and pastel on paper and also colorful capsule-shaped mounted sculptures. Powell is known for his hyper-Minimalist containers (bottles, jars, cups), and Spaulding is perhaps the most adventuresome of them all: He can make metal look like cloth, stone, or liquid. The trio’s show isn’t indicative of any trend or reacting to anything. Translation: It’s truly hip and must-see viewing for every aspiring artist.

Though not a collaboration, Material/Object is the neat sum of three parts. The show’s palette consists mostly of variations on white and gray spackled with bursts of bright primaries applied neatly, almost mechanically. What unites everything is each artist’s singular vision.

All of the work has an everyday, gently bourgeois quality — you may mistake some of Powell’s white, pockmarked “cups” for Styrofoam versions of the same, and, though indistinct, Wood’s colorful capsules will be familiar to anyone who’s ever downed a Tylenol. The world outside intrudes no further on the triumvirate’s handiwork. Material/Object‘s hermetic nature is winning, offering viewers unfiltered insights into the artists’ personalities. If all art is basically communication, then Powell, Spaulding, and Wood’s exhibit is essentially a fireside chat.

For a piece of art to qualify as transcendent, a few criteria must be met: The art must resist easy description; it must appeal to both the esthete and the plebe; and, maybe most significantly, it must be timeless. All three of the artists have pieces here that measure up.

Each contribution to Material/Object exists outside of Modernism. “Capsule #30 (AM),” one of Wood’s mounted sculptures of acrylic on wood, could have been made as early as circa 1940 or as recently as yesterday. (For the record, the piece is dated 2009.) Similarly enduring is Powell’s “Still Life with Carrot” (2008): the actual carcass of a small fish mounted on a square of white paper propped up on a narrow shelf and guarded on both sides by two “Styrofoam cups.” Here’s another criterion for you: Transcendent art must acknowledge but not imitate its observable lodestars.

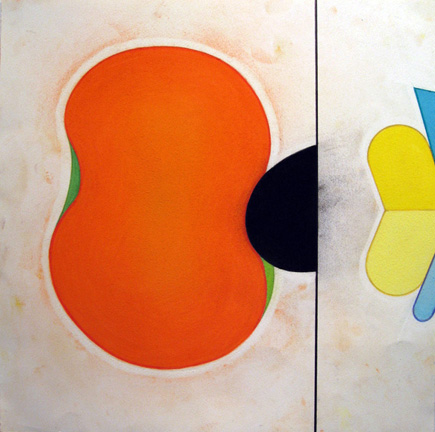

Walking into the quartered exhibition space, you are greeted by a lot of empty space — the gallery nearest to the entrance is given over to Wood’s medium-sized drawings. The pieces demand close inspection, even when you’re only a couple of inches away. Studying Wood’s admittedly simple, groovy designs — a lot of capsules, amoebae, and curving, bending blocks of inky black — you can see pencil tracings and smudge marks. Deliberate? Unprofessional? Doesn’t matter. What’s important is the perfection with which he blends colors and shades, as if he merely cut out pieces of construction paper and glued them in place. Even more charming are the borders of clean white paper that outline some of his ’70s-ish designs. He either taped off the areas or carefully “erased” them into being. Idiosyncratic? Yes. Important? Absolutely. Sweat equity doesn’t always translate into great art, but it does here.

Walking into the quartered exhibition space, you are greeted by a lot of empty space — the gallery nearest to the entrance is given over to Wood’s medium-sized drawings. The pieces demand close inspection, even when you’re only a couple of inches away. Studying Wood’s admittedly simple, groovy designs — a lot of capsules, amoebae, and curving, bending blocks of inky black — you can see pencil tracings and smudge marks. Deliberate? Unprofessional? Doesn’t matter. What’s important is the perfection with which he blends colors and shades, as if he merely cut out pieces of construction paper and glued them in place. Even more charming are the borders of clean white paper that outline some of his ’70s-ish designs. He either taped off the areas or carefully “erased” them into being. Idiosyncratic? Yes. Important? Absolutely. Sweat equity doesn’t always translate into great art, but it does here.

In the tiny side gallery, Powell’s endearing, plainspoken sculptures stand and hang like totems to anti-totemic domesticity. “cups, caps, and funnels” is a series of, well, small ruddy objects that look like cups, caps, and funnels — and also sexy parts of the human anatomy — affixed to the wall at chest-height. In the middle is a lean table atop which one of his “Styrofoam” cups stands rather majestically, calling to mind Tom Friedman, who creates regal figurative sculptures out of material as humdrum as lint, dust, and aspirin.

To get to the gallery in the rear, the viewer must traverse Spaulding’s “Text Bubbles,” several fluid floor sculptures laid side by side to resemble a powwow among spills. If you look closely enough, you’ll notice familiar shapes — an oilcan, a computer mouse, a light switch, a hubcap — below the surface.

Towering over everything in the rear gallery, figuratively and literally, is Spaulding’s imposing “Loops.” Imagine the Iron Giant’s large intestine shaped into an average-sized Christmas tree and decorated by casts of a severed workboot, an intact TV remote, half of a QWERTY computer keyboard, and other everyday objects. Spellbinding.

Material/Object is a slow but rewarding burn.

Arts Notes: Scandals and Sandals

For fans of story ballets, Texas Ballet Theater’s revival of Ben Stevenson’s Cleopatra last weekend in Bass Performance Hall was made to order. The saga of the Egyptian Queen and her Roman lovers, Caesar and Marc Antony, unfolds in 12 scenes over two acts, covering a lot of territory, perhaps too much at times, and hits most of the highlights of that remarkable life. There was plenty of gore and dramatic sweep to the evening, as well as two first-rate love duets.

Leticia Oliveira was the opening-night Cleopatra: regal, aloof, technically brilliant, a woman totally in control and intent on surviving her intrigue-ridden court. Her Caesar was Carl Coomer, a no-nonsense general whose solo work was impressive, although he faltered a bit in the twisting lifts of the duet, which left his partner draped across his shoulders on her back. Lucas Priolo danced Marc Antony with solid assurance, the same characteristic he brought to the role of Caesar the next night. His Cleopatra was Carolyn Judson, an open, more approachable monarch, whose heart seemed genuinely engaged when she danced with that night’s Marc Antony, Andre Silva. With his lack of height, Silva doesn’t always look the part of a hero when he comes on stage, but the energy and passion he brings to his dancing, the blazing technique he throws himself into with abandon, convince the audience and usually win him an ovation. (Unfortunately, this is his last appearance with the company. He joins the Great Canadian Ballet of Montreal next season.)

Stevenson set the ballet to music of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, including the rousing “Entrance of the Nobles” from his opera/ballet Mlada, for Marc Antony’s arrival at Cleopatra’s barge, one of many scenic wonders in the production. The music was taped, performed by the National Ballet of China Orchestra for a TBT tour of China that never materialized.

The Fort Worth Musician’s Union was outside picketing the programs, although what it hoped to achieve isn’t clear. TBT would jump at the chance for a live orchestra if it had the money. Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra musicians aren’t out anything. They have 52-week contracts and get paid if they play or not. (The dancers’ season has been cut from 38 to 35 weeks. The dancers nevertheless have managed to raise nearly $300,000 on their own for the company.) In a recent talk, FWSO president Ann Koonsman expressed sympathy for TBT’s plight and said she looks forward to working with the company again when it can afford live music, which looks like the season after next. — Leonard Eureka

Main Street … and You

Fort Worth’s annual Main Street Arts Festival has been criticized for its less than hospitable relationship with local artists and craftspeople. Perhaps to silence the rumblings, the festival has created an “emerging artists” category. Most of the 2009 participants are Fort Worth-local, including figurative sculptors Victor Manuel and Diana Geniz, photogs Alex Braverman and Craig Walker, jewelry designer Cheryl Campbell, tapestry artist Sherri Coffey, dollmaker Michelle Lord, sculptor Stormie Parker, and sculptors Mary Phillips and Eddie Phillips. — A.M.

Contact Kultur at kultur@fwweekly.com.