From the Ridglea Country Club’s main dining hall emanated the gentle sway of “Moonlight Serenade,” as well-to-do octogenarians slow-danced to the sounds of their youth. In a smaller dining room down the hall a more raucous affair was under way. The average age of those seated at the circular tables on an early October evening was a lot younger: Instead of World War II-era big band standards, the air crackled with magic.

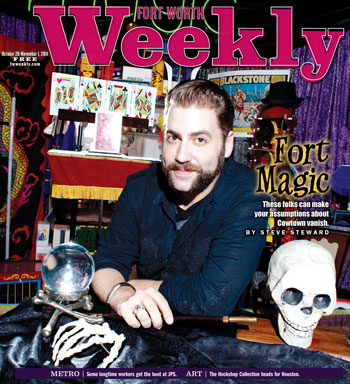

Or at least with anticipation of magic. The Fort Worth Magicians Club, at its annual banquet, was passing the torch from outgoing president Bill Irwin to incoming president Ash Adams. In this case, the proverbial torch was a literal wand, a beautiful stick of gold-tipped hardwood.

Or at least with anticipation of magic. The Fort Worth Magicians Club, at its annual banquet, was passing the torch from outgoing president Bill Irwin to incoming president Ash Adams. In this case, the proverbial torch was a literal wand, a beautiful stick of gold-tipped hardwood.

Irwin, a business systems analyst at Cook Children’s Hospital, reverently held the wand aloft.

“When it was passed on to me, I was told that the hardest part of the job was putting this somewhere where you’ll remember it the next year,” he said. In the Magicians Club, just about everything they do carries a knowing wink.

Among those in the know, Fort Worth has long had a reputation as a hotbed of magic. Since 1940, the city’s magic enthusiasts have enjoyed membership in one of the oldest and best respected clubs of its kind in Texas.

Its success and longevity are due in part to its association with Magic Etc., a shop that has been a staple among North Texas magicians for some 26 years.

“Brick-and-mortar magic stores are a dying breed, so when you have one that has every trick you could want, it helps a club like ours to really thrive,” Adams said.

The culture of the club emphasizes fun, but members also treat magic as an art form worth preserving and improving. When they’re working on duping one another, there’s not a lot of tomfoolery. Club members love performing for the public, but they also spend long evenings learning from one another and mastering new tricks. And you have to be more than a fan of magic to get in — the application involves showing your stuff to current members, who critique it.

The club’s roster has boasted notable personalities in the history of American magic, like famed apparatus inventor (and metallurgist on the Manhattan project) Wilbur Kattner and popular Las Vegas magician David Hira, as well as local luminaries such as Justin Boot founder John Justin and former Fort Worth Star-Telegram vice-president Luther Adkins. At present, the club roster is populated by everyone from magic shop employees to retired police officers. In short, it’s a veritable rogue’s gallery of quirky people — after all, how many organizations can brag about having a fire-eater for a vice president?

In terms of magic’s history, the Fort Worth club is probably most notable for its founder, Fort Worth oilman and philanthropist A. Renerick “Ren” Clark. Remembered as a sprightly man with a bald pate and a penchant for oriental décor, Ren Clark first became acquainted with the art of magic as a young boy, via a traveling post-vaudeville magic show featuring a famous entertainer named Willard the Wizard.

In terms of magic’s history, the Fort Worth club is probably most notable for its founder, Fort Worth oilman and philanthropist A. Renerick “Ren” Clark. Remembered as a sprightly man with a bald pate and a penchant for oriental décor, Ren Clark first became acquainted with the art of magic as a young boy, via a traveling post-vaudeville magic show featuring a famous entertainer named Willard the Wizard.

Willard, known posthumously as “the last of the big tent show magicians,” traveled in an extensive caravan of trucks, touring small venues and conventions across the Southwest. Clark graduated from Texas A&M University in 1924 with a degree in electrical engineering and went into the oil business, but he never forgot his fascination with Willard’s show.

His career in the oil industry took him to Canada and across the Midwest. While living in Parsons, Kan., in the ’30s, Clark wandered into a magic shop and bought a coin trick. Soon he was skilled in the sort of sleight of hand that had thrilled him as a child. Before long, he had joined the International Brotherhood of Magicians and in 1940 started the Fort Worth club as its 15th chapter. As oil boomed, so did his business, the Double Seal Ring Company. The resulting wealth enabled him to treat his passion as something more than a hobby.

In 1947, the oil magnate-cum-man-o’-magic became president of the brotherhood and immediately began a five-month international jaunt promoting the art of illusion in clubs around the world. As his reputation as an ambassador of magic grew, so did the number of local magicians’ groups. Soon, magic clubs were appearing across the globe like doves out of a hat. Upon word of an upcoming visit by Ren Clark, club leaders would scramble to invite new visitors, hoping that the oilman’s personality and passion would inspire them to become members.

His enthusiasm for magic was at least as ardent at home as it was abroad. According to friend and longtime club member Bob Utter, Clark loved coin tricks. “He’d start with one and then all of the sudden he’d show 10 in his hands,” Utter said.

His enthusiasm for magic was at least as ardent at home as it was abroad. According to friend and longtime club member Bob Utter, Clark loved coin tricks. “He’d start with one and then all of the sudden he’d show 10 in his hands,” Utter said.

Clark was also famed for his Asian-themed productions. “Ren really liked Asian things. A lot of his tricks involved long, flowing Asian silks, umbrellas — he’d make umbrellas appear out of nowhere,” Utter recalled. “He went all out — he would dress in these Chinese costumes, put on the eye makeup, the whole nine yards.”

Clark’s act was more than just small-scale sleight of hand. “His production had all kinds of intricate folding boxes that he’d had made special in Japan, and he used a lot of birds too,” Utter said. Indeed, Clark’s home boasted an aviary, with a motley flock of exotic birds.

As if cockatiels flying out of kimono sleeves weren’t enough, Clark’s penchant for post-war exotica spread to other interests, particularly in the Western Hills Hotel (now long departed) on Camp Bowie, notable for its tiki-themed Polynesian Village restaurant and Sunken Galleon bar and equally famous for its “mermaid,” a woman who swam in costume in a giant aquarium behind the bar. Clark had a stage built in the Galleon, big enough for his elaborate act.

The hotel was a hit among socialites, in part because of its then-trendy design scheme, but also because of Clark’s business partner, none other than Desi Arnaz. In other words, Clark was one of those mischievous grandpas who produces quarters from a kid’s ears, except that he did it in a fantastic tiki room and the kid was Desi Arnaz Jr.

Ren Clark passed away in 1991, leaving a legacy of magic and showmanship that would inspire many, including a Fort Worth kid named Ash Adams. When he was about 13, the budding illusionist got to meet his idol — by doing his act in Clark’s home.

“He asked me to come over and perform at his house,” Adams said. “His house was crazy — he had a stage and all this cool stuff. He was fascinating.”

“He asked me to come over and perform at his house,” Adams said. “His house was crazy — he had a stage and all this cool stuff. He was fascinating.”

Under Clark’s stewardship, the FWMC had grown in popularity, reaching its heyday in the 1970s, during the period when magicians like Doug Henning and charlatan Uri Geller regularly appeared on television.

In the ’50s, local magic fans were delighted by Utter’s televised illusions, under the sobriquet of Mr. Mystic, who hosted a program of the same name on KXAS/Channel 5.

“Mr. Mystic was fun and challenging, because everything was live back then,” Utter said. “Tape just wasn’t really used, so if you had a problem with your trick, you just had to smile and move on.” The program aired after school, five days a week, meaning that Utter had to come up with new tricks every day.

Utter is a tall, convivial, retired PR man partial to multiplying-ball-type tricks. He joined the Fort Worth Magicians Club in 1958. “In those early years, magicians were dedicated to providing shows to the community,” he said. “We would do shows at hospitals and places like that free of charge.”

They also performed for fun. Utter, Clark, and a few other members did magic tricks at places like the former Blackstone Hotel downtown and table tricks at the aforementioned Polynesian Village. “We’d do walk-around table bits,” Utter recalled, “just doing little fun tricks with whatever was on hand — toothpicks, utensils, napkins. It was a lot of fun.”

While magic was popular nationally through the ’60s, Utter said, by the end of the ‘70s, interest in the art began to wane, and the Fort Worth club’s membership dropped off accordingly.

“You used to get a lot of traveling magicians, but after the ’70s, you didn’t get too many of them coming around and doing shows in the cities,” he said. “It was too bad, because that’s where new magicians are born. They see a certain trick, and it makes them say, ‘I want to learn how to do that.’ ”

“You used to get a lot of traveling magicians, but after the ’70s, you didn’t get too many of them coming around and doing shows in the cities,” he said. “It was too bad, because that’s where new magicians are born. They see a certain trick, and it makes them say, ‘I want to learn how to do that.’ ”

The club’s popularity picked up again in the ’80s and ’90s, with membership topping 100 members. In the ’90s, the Fort Worth Magicians Club held annual shows in what used to be Caravan of Dreams, the famous downtown venue whose space is now occupied by the Reata restaurant.

“We would do these giant shows at Caravan,” said Adams. “I was in a bunch of them when I was a teenager. The shows were highly publicized — we’d have radio DJs host them, and we’d hold them over three nights.” The Caravan affairs were more than just card tricks — the club really went all out. “We’d get some big acts from Texas and sometimes even from across the country,” he said. The shows “would be a good mix — you’d have a comedy act; a snappy, kind of Vegas-y manipulation act; a sleight-of-hand guy; usually some kind of novelty act — a great juggler or something like that … . And then we’d close it with a big, full-stage illusionist type guy.”

Adams’ theory is that magic’s currency comes in waves, and when he got back to Fort Worth about five years ago, several years after graduating from Yale University, the magicians’ group was at the bottom of one of those waves. He had spent the intervening years in a magician’s version of the corporate world, living in New York and working as General Motors’ “corporate magician,” appearing at the auto manufacturer’s trade shows and training events.

“When I came back into town, [the club members] were all new people,” Adams said. “They didn’t know how the club used to be, and a lot of the older members had fallen out or disappeared.” He sought to reinvigorate the society. “I came back in with a few of the older members to breathe that life back into [the club] again. It has such a rich history,” he said.

He points out that mainstream stars like Criss Angel and David Blaine have kept the art form in the public’s eye, as well as the odd illusionist on shows like America’s Got Talent.

“Magic’s still hot,” he said.

Adams said the club would like to begin holding big shows again, though it has yet to find an appropriate venue. Currently, the biggest event on local magicians’ horizon is the annual Texas Association of Magicians Convention, scheduled for Fort Worth in 2014.

Public performances aside, however, the club’s main purpose is to develop the talents of its members. “We want to promote and further the art of magic,” said Adams. “I truly believe that magic is one of the great art forms … . It allows you to live in this moment, where for [the audience], the laws of the natural world are flipped upside-down.”

Aspiring members are required to perform a brief routine for the rest of the club, after which the current members critique the act and vote yea or nay on accepting the applicant. Most meetings are partly open to the public and, given the nature of magic, partly held behind closed doors. The inherent secrecy of every illusion’s mechanics is an important element of what makes magic magical. By excluding outsiders, the club offers a gentle reminder that while the art is fun, it’s still performed by devoted artisans, and the tricks of the trade are open only for those who work to uncover them.

These days, the club meets once a month at the Tarrant County College campus downtown, and members often perform at TCC events.

But the club also brings out-of-town magicians here to perform for local practitioners. Houston’s Scott Wells and the world-renowned Arsene Dupin, a French street performer known for studying under Marcel Marceau, have both performed at Magicians Club events.

The club also hosts new product demonstrations at Magic Etc. a couple of Saturdays a month. While the demos are more for magicians than the general public, the store on Forest Park Boulevard opens early, and anyone can buy the new gear at a discounted price.

The club also hosts new product demonstrations at Magic Etc. a couple of Saturdays a month. While the demos are more for magicians than the general public, the store on Forest Park Boulevard opens early, and anyone can buy the new gear at a discounted price.

“Magic-shop demonstration is a culture unto itself,” Adams said, “and it’s integral to getting people interested in it. It’s a different type of performance, and the people who are good at it really have a unique talent.”

The club also offers its members workshops that are a magician’s version of a peer critique: Other members go over an individual’s act with a fine-tooth comb, sort of like the Toastmasters, if a Toastmaster speech ended with a puff of smoke or a lovely assistant getting sawed in half.

Magic has a long way to go before the average Cowtown resident lists sleight of hand as a hometown source of pride and entertainment — it’s not going to replace barbecue or country music any time soon as one of Fort Worth’s salient selling points.

The Fort Worth Magicians Club has produced a number of famous magicians, and Adams, for instance, has performed in Las Vegas casinos like the Tropicana. But no matter how popular a David Blaine or Penn and Teller-type act might be on the national scene, local magic still flies mostly under the radar. And making a living as a magician is about as tough as you’d expect.

For now, the magic “scene” here is limited mostly to the Magicians Club itself, plus the infrequent, heavily promoted shows like the old Caravan of Dreams productions.

Randi Rain, a Fort Worth trick designer, fire-eater, and illusionist who was just inducted as the club’s executive vice-president and program chairman, thinks magic could blossom in Fort Worth if North Texas had a bigger theater culture. Unlike local bands, for whom a bar, club, or coffee house is a suitable venue, magic tends to favor theaters.

“North Texas needs more theaters,” Rain said.

Utter concurred. “There used to be a lot of small theaters, like the Majestic downtown, but now they’re all gone,” he said.

Rain also pointed out that a lot of commercial work for magicians comes from casinos. “If Texas legalized gambling, I think the magic scene would become a lot bigger here,” she said.

Still, Fort Worth does recognize its magical treasures from time to time. On Tuesday, the city council approved a proclamation offered by council member Joel Burns, declaring the last week of October to be “Magic Week,” in honor of the club and the anniversary of Harry Houdini’s death on Halloween in 1926.

At the club’s banquet at the Ridglea earlier this month, council member “Zim” Zimmerman, whose previous association with magic involved helping make the city’s streetcar project disappear, was on hand to recognize Adams as an honorary member of the Fort Worth City Council and to present the club with some items — official gold coins and a deck of cards bearing the city’s brand — that members no doubt could put to use in their tricks.

At the club’s banquet at the Ridglea earlier this month, council member “Zim” Zimmerman, whose previous association with magic involved helping make the city’s streetcar project disappear, was on hand to recognize Adams as an honorary member of the Fort Worth City Council and to present the club with some items — official gold coins and a deck of cards bearing the city’s brand — that members no doubt could put to use in their tricks.

“Magic is ageless,” Zimmerman said, and he talked about how groups like the Magicians Club help nurture kids’ fascination with the art and turn it into a lifelong interest.

As Zimmerman and Adams stepped down from the podium, the genial Bruce Chadwick took the stage. There were indeed a few youngsters seated at tables, eagerly watching the master of sleight of hand set up a trick involving oversized playing cards.

Over the course of his performance, he offered a story about how his own interest in magic developed. He brought out the first trick he’d ever learned, involving a tin can and disappearing water. As he tinkered with it, a fake snake shot out. It was the sort of trick a 14-year-old boy lives for, and indeed, the teenagers in the audience were cracking up. (Fort Worth’s Society of Young Magicians, started by Adams and a few of his peers many years ago, died out but has recently been revived.)

Inspiring kids to take up the wand and make their allowances disappear is one step for furthering Fort Worth magic’s future, but venues are still a big problem. The attacks of 9/11 severely hurt theme parks, which had been bread-and-butter spots for magicians, Adams said.

“Then, when you had people getting interested in magic again because of the David Blaines and Criss Angel types, the recession came along — now people aren’t even going to Vegas that much,” he lamented.

Could magic succeed on a smaller level, without the big spaces needed for complicated acts? “I think magic might take the route of comedy — you find more comedians playing bars and rock clubs rather than traditional comedy venues, and I think that magicians could capitalize on working that smaller side,” Adams said.

At the banquet, renowned cruise ship magician Chip Romero flung steel rings into the air, joining them in his hand as he caught them, spinning them apart and spreading them again in long chains. Across the faces of the audience, you could see other magicians and would-be magicians searching for the seams in his act, trying to figure out how he could appear to defy natural law.

On that evening, in one small room at a country club, it looked like magic could live forever.

“Part of what I love about magic [is that it] makes you question everything around you,” Adams said. “I think that is really important, especially right now.”

You can reach Steve Steward at stevesteward16@gmail.com.