Though he was still a teenager, Six2 had already experienced how high life could take him and how quickly it could try to erase him. As he stood on a Hemphill Street corner looking to peddle a pocketful of crack one day in 1996, he reflected on all that had happened in the previous month. In a 30-day period, the tall, quiet rapper had been arrested for possession with intent to deliver crack cocaine, had escaped a gun pointed at his forehead, and was relatively homeless, bouncing from one unwelcoming house to another.

Six2 and another rapper, El Dog, were performing as the duo Gena Cide and had seen their Dirty South anthem, “Da Citi,” receive major airplay on K-104 (KKDA/104-FM), the broadcast epicenter of North Texas rap. Six2 was a junior when he dropped out of high school, believing he was on his way to great wealth and fame, but the streets had other plans for him.

Six2 and another rapper, El Dog, were performing as the duo Gena Cide and had seen their Dirty South anthem, “Da Citi,” receive major airplay on K-104 (KKDA/104-FM), the broadcast epicenter of North Texas rap. Six2 was a junior when he dropped out of high school, believing he was on his way to great wealth and fame, but the streets had other plans for him.

Six2 recorded the song “Deeply Thinkin” out of frustration at feeling forced to be a gangsta. The song reached the ears of rap icon Dr. Dre, who invited Six2 out to Dre’s homebase of Los Angeles to lay down some tracks on a Dre album in progress. Six2 thought he would be a success story out of his Stop Six neighborhood, one of the poorest in North Texas, but he mainly ended up seeing the ugly side of the business. He has been used, ripped off, lied to, and left to wither on the side of the fast lane to success.

But he’s not done yet. You could even argue that he’s never been better.

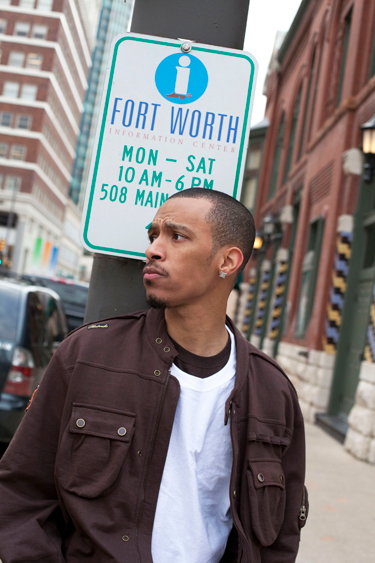

As Six2 was fleeing Texas to join forces with the who’s who of hip-hop back in ’96, 13-year-old Lorenzo Zenteno received his first computer, a gift from his mother. The teenager had been fiddling around with hip-hop rhymes in his Northside barrio but didn’t have much of a musical product to promote. Undeterred, he started building the Smoothvega brand, even shaving his new alias into his head. Now, after years of relentless self-promotion, he has taken over as one of the main faces of Fort Worth hip-hop.

To date, Smoothvega has organized 15 hip-hop events, each under the banner of Total Pandemonium. He uses the opportunity to showcase not only his talent but also that of other local hip-hop artists, national hip-hop artists, and teenage dance teams. He has broken attendance records for Fort Worth music events by appealing to younger audiences, for whom he wants to serve as a role model.

These days, Smoothvega may have some competition. Andrew McCollough, who goes by Dru B Shinin’, left his career as a stockbroker to pursue music full time. He and his two bandmates, EyeJay and The Shark, recently released Dirty Money Painting, which may be the new benchmark for what is possible (and expected) in local hip-hop.

Big and musical, the album appeals to fans of many genres. Over EyeJay’s fat beats and swelling atmospherics, Dru raps about the totality of his experience. For a TCU-educated son of a minister, he has walked down some dark alleys. Though he released two albums in 2010, Dru is only beginning to make a dent in the big plans that he has for both his career and the Fort Worth rap scene that he is helping build.

All the trails that have been blazed are a boon for the newest crop of Fort Worth hip-hop artists. Someone like Ron Brown, who goes by Rkade, can focus solely on the message in his music while others worry about a business model.

After years of struggle and hard lessons learned, 817 hip-hop artists have finally broken free of the need to be part of some larger machine or some materialistic thug image. Rap acquired a bad reputation thanks to gangsters who associated violence, misogyny, and expensive car collections with hip-hop music — lyrical and promotional motifs that are largely absent in Fort Worth hip-hop.

Fort Worth hip-hop artists are vastly different people coming from a variety of backgrounds, but they are unified by one musical element: They portray life as it really is. Here there are no fictional personae or invented rifts between rival artists.

Rap, unlike loud, distorted rock ’n’ roll, offers no place to hide. The truth is right there, front and center, constantly adapting as the beats beneath it bounce and push. Lyrical authenticity is a hard thing to fake, but, opposed to a catchy style or sound, it may be what defines Fort Worth rap music.

When Six2 was a kid in the ’80s, he would sneak into his brother’s car to listen to gangsta rap’s pioneers. N.W.A.’s “Gangsta Gangsta” inspired him to write songs of his own. He’d count out a meter for the verses and invent a catchy chorus. The talent to create a hook, and his heady mathematic cadences, set Six2 apart from the other early local rappers.

At first, he did it to be like the older guys who would rap and breakdance outside of the dollar movie theater in the ’hood. By the ninth grade, he and a few friends had a gangster rap group they called HHAN (Hard Headed Ass Niggaz). “We were the teenagers that went against the grain: smokin’ weed, getting drunk, skipping school, shootouts,” he said about the inspiration for the group’s material.

By 1994, Six2 and El Dog had splintered off into Gena Cide and released an album, Waste Uva Color. After K-104 started spinning “Da Citi,” Six2 and El Dog felt they had found their calling and had no need to keep attending Eastern Hills High School. “I thought we were going to be rich,” Six2 said.

In addition to Six2 and El Dog, local rapper Twisted Black was concurrently putting Fort Worth on the map. In 1995, the now-incarcerated 34-year-old sold 10,000 copies of his album One Gud Cide: Look What the Streets Made in 30 days.

In 1996, Six2 befriended Dallas rapper/producer Erotic D, who was working in Los Angeles with the D.O.C., a man partially responsible for the early success of icons Eazy E and N.W.A. Erotic D gave a copy of “Deeply Thinkin” to the D.O.C., who, in turn, gave it to industry pioneer Dr. Dre, who paid the D.O.C. to travel to Fort Worth and find the kid responsible for the powerful lyrics. “Nowadays, I ain’t happy to see the sun rise,” Six2 raps in a mellow, smoked-out cadence. “Where do ghetto children go when they close they eyes? I done seen so many lost souls, it’s hard to stomach / It’s like a jungle out there / Makes you wonder how I keep from going under,” referencing one of rap’s earliest hits, Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message.”

At first, Six2 didn’t believe his luck had changed so quickly. He laughed off a friend’s initial report that the D.O.C. was in town looking for him. When Erotic D met Six2 at the downtown Dickies factory with a contract containing the signatures of both Dr. Dre and the D.O.C., the young upstart turned into a believer.

Although he wasn’t supposed to leave the state because of pending felony charges, Six2 couldn’t say no to a veritable hip-hop apotheosis. So he signed and immediately left for Los Angeles.

Over the next few years, Six2 developed his solo album while writing material for Dr. Dre, who was working on a follow-up to his 1992 groundbreaking triple-platinum hit album, The Chronic. Six2 had much better quality of life in L.A., hobnobbing with famous rap artists and generally enjoying high times, but he had yet to find any personal riches.

In 2000, Six2 hit the road for the Up in Smoke tour with Ice Cube, Eminem, Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre, Kurupt, and others who now sit in the pantheon of hip-hop. Six2’s album was finished, but his associates kept pushing back the release date because “It wasn’t the right time,” he said.

After the tour, Six2 surrendered back in Texas to settle the old possession-with-intent charge from his street life days. He didn’t want the police to storm the stage while he was performing. After his six-month incarceration, he expected to pick up where he’d left off. He had penned two songs, “Xxplosive” and “Bitch Niggaz,” on Dr. Dre’s newest multiplatinum hit album, The Chronic 2001, and his debut solo album was ready and waiting to hit stereos around the world. “When I got out of jail, I thought a helicopter was going to pick me up,” he said.

Instead, shortly after his release, he discovered that the D.O.C. had co-opted his record, put his own face on the cover, kept the vocals that Six2 had recorded, called it The Deuce, and cut Six2 out of the profits. Worst of all, thanks to that lengthy contract he had signed at the Dickies factory in 1996, Six2 had no recourse.

Today the 6-foot-2-inch rapper hangs his head and sighs about what happened. “It depressed me,” he said.

When he finally washed his hands of his association with the D.O.C in 2005, rap and R&B crossover artist Timbaland called and wanted to collaborate. Thinking this was his opportunity to right the wrongs and re-join the high life, Six2 headed to Miami to work with Timbaland and start anew on a solo album.

During that time, he wrote or co-wrote the songs “Board Meeting,” “Wait a Minute,” “Mean Walk,” and “Release,” but he now gets full credit only for his own Six2 single, “Mean Walk.” His work from that period ended up on other artists’ albums. Without telling him, Timbaland sold the ironically labeled “Wait a Minute” to the Pussycat Dolls for their PCD album. Six2 didn’t know what had happened until the Dolls were already shooting the video.

During that time, he wrote or co-wrote the songs “Board Meeting,” “Wait a Minute,” “Mean Walk,” and “Release,” but he now gets full credit only for his own Six2 single, “Mean Walk.” His work from that period ended up on other artists’ albums. Without telling him, Timbaland sold the ironically labeled “Wait a Minute” to the Pussycat Dolls for their PCD album. Six2 didn’t know what had happened until the Dolls were already shooting the video.

He eventually sued the group, and a judge awarded him credit for the song and a quarter of a million dollars, most of which was eaten up by lawyers’ fees. Lesson learned, once again.

Hitching his wagon to the big names in the music industry was a mistake in retrospect. “It’s the problem I got with a lot of mainstream dudes,” Six2 said. “They hold people like me back. I couldn’t fight that shit. To this day, I tell people to read your paperwork, get a lawyer.”

Since finally taking his career into his own hands, Six2 has done some of his best work. He and independent Houston artist Big Mike worked together on an innovative blues guitar-based rap song “Down Home.” He finally published a solo Six2 album, Affiliated, a record that consists mostly of bits and pieces of unreleased material. Dr. Dre gave him his rightful song credits on The Chronic 2001, and he now lives in an apartment in Arlington off royalty checks, which are growing smaller by the year. “I’m not comfortable by a long shot,” he said, although at least he doesn’t have to sell crack on the street corner anymore.

Being back in Texas has its advantages –– and disadvantages. Escaping from the mass-market rap money machine has given him artistic control and the ability to take full credit for his work, but he’s frustrated at the way local rap fans still cling to the big-name artists on the radio. He feels that many of them got to where they are by “throwing others under the bus,” he said.

In 2010 he tied up his past in an album called Concrete Evidence, which was designed to “let people know where I’ve been,” he said. He and Money Militia are currently promoting a track, “You Girl,” and launching a social media campaign for attention. His hip-hop club/dance track “Monsta” made the rounds last year too.

For all the fun he’s had making music, 2011 is the year for him to get serious. “I’m more focused on me now,” he said. He’s working on his masterpiece, an album called Sincerely Yours, which will drop sometime in the fall. “It’s to everyone I worked with, everyone I plan on working with, people I have problems with, people who have problems with me,” he said.

He has a lot of pent-up emotion about the ups and downs in his career, and he’s about to let loose, which will take him right back to where he started. “It’s my heart waiting to get out,” he said.

Around the time Six2 was waging a court battle over “Wait a Minute,” Smoothvega was growing concerned about the content of the musical artform that he loved so much. In 2007, he told the Weekly, “So many artists are about image –– not real life –– and that’s what I can’t relate to in rap music right now.”

While national rappers were more concerned with champagne-popping and sex than ever before, Smoothvega kept his nose to the grindstone. When he dropped the song “Apology Letter” in 2008, he didn’t know how much his heartfelt statement to his parents would end up meaning to him. “Sincerely yours,” the song starts, “I apologize to Mom and Dad for not being the perfect son / I’m sorry, Mom / I know there’s so much more I could have done / You were the loving mother / I was the bad kid / I wish I could take back all the wrong I did back then.” So much for the stereotypes about rappers.

When his parents moved here from Mexico, they were hoping to give their family opportunity. Smoothvega has made the most of the gift even if life hasn’t always been easy. He married his high school girlfriend Angie, and in 2005 he held their infant son Alexander in his arms as the child died from complications from a premature birth. Vega went on to rap about the experience in his album 3.10.85, which is the rapper’s birthdate.

In December 2009, Zenteno’s mother Maria died unexpectedly, which was another huge emotional setback for the then-24-year-old, but he knew his mother would want him to continue with his “Self Made Movement,” a term stamped on all of Vega’s CDs and that will eventually become the name of his record label. “The day after my mom’s funeral,” he said, “I woke up confident and alive. I thought, ‘You know, now is my time.’ ”

A few months after his mother’s passing, Vega’s daughter, also named Maria, was born. Despite his wife’s complicated pregnancy, everything has worked out beautifully. They are now expecting a brother for Maria, so the rapper and promoter wants to kick his already busy and profitable career into overdrive.

Listening to Six2 and other local artists like Twisted Black and Immortal Soldierz convinced a teenage Zenteno that success in local music was possible. He also learned from their mistakes. Smoothvega has never been one to trust anyone else with his finances, so he takes control at every step.

“People make excuses,” he said. “The say they’re not successful because they don’t have the resources, but I have made money doing this. … The marketing element wasn’t part of the Fort Worth hip-hop scene before I came along.”

Before the birth of his daughter, Smoothvega had held only one job, at a Westside fast food restaurant, where he would write the address to his website on the backs of receipts when time permitted.

When not working in the studio, he has spent the last decade on the social networks, constantly connecting with potential fans. “I’m aggressive,” he said. “You have to be as an independent artist.”

By the time Smoothvega’s listeners had expanded into the thousands and his cell phone contained the numbers of widely acclaimed international artists like Chino XL, Lil’ Flip, and Frankie J, he started putting on the Total Pandemonium events. Charging $15 a head, he packed thousands of people, mostly kids and young adults, into Fort Worth venues like Club Chrome and the Ridglea Theater. In the span of 12 months from August 2007 to 2008, his events profited more than $100,000 –– money that he immediately reinvested in himself and his crew of rappers and singers.

Perception, Smoothvega said, is half the battle. “People say to not judge a book by its cover, but they only say it because people really do,” he said. “You better have a pretty cover.”

A quick internet search reveals dozens of high quality Smoothvega videos (one for just about every song he’s ever done) as well as professional electronic press kits for both him and Louie Evol, the singer whom Self Made Movement will be pushing next.

As a result of his visibility, Smoothvega is looked to by aspiring artists for help. Attaching his name to an event gives it legitimacy and guarantees a crowd. “I’m always part of anything that has happened over the last five years,” he said.

People look up to Smoothvega for the way he runs his business and also for the way he lives his life. Some assume that he never drinks and smokes because he wants to take the high road, but sobriety was a business decision. “I didn’t want to create a spending habit outside of music,” he said.

Although the artist’s music catalog is still relatively small, he has already reached enviable heights by doing things his way. He recently landed a deal to do the music for an upcoming documentary about ex-TCU and current New York Jets running back LaDainian Tomlinson, Camp LT.

In the music, however, the rapper prefers just to fit in rather than make any big artistic splashes. The wider the appeal, the better, he believes. “I don’t make rapper’s rap,” he said. “I make music for the people who keep up with me and are already fans of mine.”

In the music, however, the rapper prefers just to fit in rather than make any big artistic splashes. The wider the appeal, the better, he believes. “I don’t make rapper’s rap,” he said. “I make music for the people who keep up with me and are already fans of mine.”

If other local rappers poke fun at Smoothvega’s music because of its mainstream appeal or his limited catalog, he doesn’t care. “I’m not consumed with competition,” he said. “I stay in my lane and do what I do best. You find your identity and go forward with who you are.”

What Smoothvega really wants to be is a leader and a symbol for what is possible. “I am the hope for people that live in the Fort Worth barrios,” he said. By throwing the Total Pandemonium events and actively searching for young Fort Worth artists to share the stage with big national names in hip-hop, he believes that he is “leaving a lasting impact and touching the future,” he said. “I want to utilize my resources and the relationships I have attained over the course of my career and assist artists by giving them opportunities I was never given.”

By shaping things to come in such a proactive way, the solidly built Smoothvega could reach a comfortable stopping point, but he is moving along. In 2011, he will release Exclamation Point, his most ambitious album to date, which includes contributions from Bun-B, the legendary Scarface (from Getto Boys fame), and Louie Evol. He has triumphed over everything life has thrown at him and doesn’t crave attention from outside sources.

“The days of me feeling like I’m going to be a nationally signed recording artist are long gone,” he said. “I’m more about being an independent powerhouse, making a substantial amount of income doing that.”

In many ways, Dru B Shinin’ bucks every stereotype ever leveled against a rapper. Dru was born in Korea and then adopted by a Disciples of Christ minister in Topeka, Kansas. He got a scholarship to TCU and, after he graduated, a job as a stockbroker –– not exactly the thug life.

But to hear either one of his 2010 releases, Admission One and Dirty Money Painting, you might assume that Dru is native to the streets. In songs like “Thank Me,” he urges listeners to “Please take a little time out of your day and thank your local drug dealer / They go through a lot to provide you the product that you so much enjoy.”

But to hear either one of his 2010 releases, Admission One and Dirty Money Painting, you might assume that Dru is native to the streets. In songs like “Thank Me,” he urges listeners to “Please take a little time out of your day and thank your local drug dealer / They go through a lot to provide you the product that you so much enjoy.”

The juxtaposition of the slightly shady with the spiritual is the basis for Dirty Money Painting. It is “beautiful and intellectual, but it’s also a picture of dirty money,” he said. “I’ve made a lot of that, and I want my music to be relatable.”

Dru hits an entirely different note with “Heaven in the Sky,” an emotional musing on how we persevere through unthinkable tragedies. In all of the songs on his album, Dru shows off his penchant for multisyllabic rhymes and unique approaches to vocal rhythms.

Despite his hard-edged songs, the Korean with the mischievous eyebrows and serious eyes treats others with respect and kindness. Instead of putting others down (as some rappers do), Dru adopts a determined tone and describes his commitment to the music. Over soaring, powerful synth chords on “The Promise,” for example, Dru verbalizes his promise to keep the faith in music no matter what aspects of modern life try to get in the way.

Performing with musicians rather than a computer is one thing that sets Dru B Shinin’ apart. And his way was paved in some ways by the first hip-hop group to rock out, so to speak: the Rivercrest Yacht Club. Perennial readers’ choice winners for best hip-hop in the Weekly’s annual Music Awards, the Yacht Club is more of an indie-band but one with a serious rap addiction. Dru B Shinin’ is much more traditional.

When Dru moved to Fort Worth from Topeka, he didn’t see much of a scene. He felt like an “outsider” in the street-centered Eastside world and in Vega’s Northside gatherings. He met other aspiring rappers and shared a frustration about the difficulty of finding local listeners.

“Fort Worth is so hungry to find something to call our own,” he said. Local pop-funk crossover artists Rabbit’s Got the Gun were sharing their stages with freestyle artists Big Cliff and J. Kush, the Yacht Club was gigging with popular indie-rock bands, and LAZËR was mixing live instrumentals with Eurotrash and hip-hop, but, otherwise, hip-hop was taking a back seat.

Dru and his crew initially made inroads into the scene via the Fort Worth Music Co-Op, which booked them a few shows, included them on a compilation CD, and eventually handed them a monthly gig at The Cellar.

Dru used the opportunity to invite as many rappers as he could find to join him for the events. “They came out of the woodwork,” he said. Before Dru’s entry into the scene, many aspiring local rappers made music in their bedrooms and didn’t feel comfortable performing anywhere.

The Dru B Shinin’ events are now banner nights at The Cellar, even if much of the crowd has similar aspirations. “Everyone who likes your stuff is probably also an artist,” said Dru’s manager, Isaac Williams. “If you fall off, they are ready to take your place.”

EyeJay, an alias for producer and multi-instrumentalist Irv Jones, tells the people he works with to remember two things: “I know at least two other rappers on my street” and “Everyone has a cousin who makes beats,” meaning that the hip-hop game is much more crowded than most people realize.

Instead of fending off the competition, Dru finds power in working together. He would like his musical product to reach people far beyond Fort Worth, and he believes that the road to more mainstream success depends on the unification of the artists in the city.

The next step for the scene is to convince listeners that local sounds are as good and as relevant as any of the entries on Billboard’s list of top rap songs. (At the top of the chart as of the time of this writing is the catchy but predictable and essentially meaningless “No Hands” by Waka Flocka Flame.) “The scene becomes strong when people value the music as much as the national CDs they buy,” Dru said. “That comes from confidence.”

Dru and the Sphere Music Group, founded by Jones, Williams, and Dru, aren’t afraid to display a sort of inoffensive bravado or to plan on catering to audiences in the thousands, not the dozens normally in attendance now. Dru and company have made handfuls of videos for Dru’s music to “introduce ourselves to more people,” Williams said.

When making a video, like the latest one, set to “Range” from Dirty Money Painting, “We make it as if a million people will watch it,” Dru said. “We believe in ourselves. It’s all about presentation. We make it bigger than it is.”

Dru is currently working on his next full-length album, The Clean Up, which will be ready in the summer.

As much as Dru and his crew put faith in what they are doing, they also want to help those around them. Someone is always at EyeJay’s South Fort Worth home studio looking for a beat or advice. Jones is currently recording many artists, and he co-writes and produces a weekly collaboration that he calls Westside Wednesdays. In the future, Sphere Music Group wants to set up an official studio and headquarters in West Fort Worth for aspiring rappers to visit, feel supported, and get their creative juices flowing. Belief that a community is only as strong as its weakest member is more than a mantra for Dru B Shinin’ and company. Success is a shared experience.

Ron Brown, a poet and rapper who goes by Rkade, doesn’t really concern himself with the concept of success. “I don’t care about money,” he said. “It’s not my main goal. I always just wanted to help people.”

Ron Brown, a poet and rapper who goes by Rkade, doesn’t really concern himself with the concept of success. “I don’t care about money,” he said. “It’s not my main goal. I always just wanted to help people.”

The overly polite, skinny 26-year-old in jeans and a nice polo-style shirt reads a Forbes magazine with Jay-Z and Warren Buffett on the cover as he calmly explains, “I’m able to express myself and the things I’m going through. It’s become therapeutic.”

As a teen, Rkade bought into the whole rap-to-riches mentality of the popular artists of the ’90s like Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls. “But now that I’m older, I got out of the fantasy world,” he said. “I had a reality check.”

Smoothvega introduced Fort Worth listeners to Rkade by including him on the song “One Hundred,” and Brown used the exposure to advance his career and rethink his message. He is currently working on his debut album, Find’n Me: Road 2 Recovery, which he plans to finish and release in late summer. About the content of the 17 tracks, he said, “There are a lot of things I’ve done that I’m not happy with. I’m going to express them and move past it. I go through a lot of stuff. I’m maturing in the right direction, but I have a long way to go.”

Tupac might roll over in his grave if he could see the newest generation of hip-hop artists, who are distancing themselves from the “Thug Life” image that he created and that has somewhat reigned over the rap mythology since the beginning.

Rkade doesn’t even want to be called a rapper. “I’m a motivational speaker,” he said. “A lot of us are going through the same thing. A lot of people don’t have a voice, but I can be a voice for others.”

The Hurst native works full time doing technical support for a large corporation. He saves the persona also known as “Mr. Fort Worth” for his free time, because as much as he loves music, his total personal evolution is the priority.

Originally, rap music was perceived as the artform of the disaffected poor. It was the voice of those who felt the world had conspired against them. Many rappers and fans feel that as soon as the music money machine figured out that rap could be profitable, the genre lost its spirit. As artist after artist either emulated the pioneers or put energy into the rap mythology, many claimed that hip-hop was dead. With so much invested in the image, the truth got lost.

Fort Worth, as a hip-hop town, sprang to life only when Smoothvega, like a Pied Piper, assembled young adults into large venues by the thousands. Still, when Dru B Shinin’ tried to find a Fort Worth hip-hop scene, he didn’t know where to look.

Thanks to his effort, The Cellar now is a regular mainstay of Fort Worth rap, but the genre is lagging behind rock and electronica as far as how the music is disseminated. Until recently, fans could find local rap albums at places like the Polywreck Shop, but almost all the CD stores have now closed. “Everything is going digital,” Smoothvega said.

Indie-inclined listeners have turned to blogs and internet radio for years to find the latest next big thing, but MTV and FM mega-radio continue to dictate trends in hip-hop. Local hip-hop artists are trying to stake a claim on cyberspace, especially on Twitter, and make money selling music online. The going, though, is rough, and they’re not getting enough help from local media.

People need to “wake up,” Six2 said. “People here aren’t behind the artists. … Clubs don’t support the local artists, and so many people need to be heard.”

He feels that too many fans still find excitement in the mainstream. “They’re waiting on a dude they hear on the radio,” he said.

Rkade has no use for radio. A lot of what he hears on local rap stations is “garbage,” he said, but he is unfazed. “Music is reverting back to the past,” he said. “The game will revert back to the lyrics, and history will repeat itself.”

Although a handful of rappers in the last 15 years have depicted reality, the “Deeply Thinkin” songs of the world largely gave way to songs about loads of cash, fast cars, and faster women.

Interested parties have a wealth of local hip-hop artists to choose from who have a social conscience and a true message, including RLCthaRod, who is working on a doctorate in theology at TCU; Alan Royal, an articulate former teacher who is about to write his master’s dissertation for an advanced education degree; Snow Tha Product, an unshakable and bold young voice; Birds Eye Blues, a group that waxes about the social consequences of poverty; Twisted Black, who has continued to make albums in prison by rapping over the telephone; JaNo, a former military man who has an audacious, street-style lyrical technique; Royal $outh, a rapper whose “White and Purple” remix of a Wiz Khalifa song is making the rounds in local clubs; Playa Rabbit; Bone; Killa MC; J. Quest; Wrex Washington; and many more.

Better yet, at long last, hip-hop artists from all over the city are finally starting to work together in a unified manner. The same thing happened a few years ago in Houston, and many artists benefitted as a result. Houston rapper Chamillionaire will be one of the featured speakers at this year’s SXSW Music Festival and Conference. Five years ago, he was a relative unknown.

Could the same thing happen to Fort Worth? The quality is absolutely here, so it all depends on how well rap lovers will support their local artists. Dru B Shinin’ is staying positive. “Hopefully, more listeners will start priding themselves on finding their own unique taste,” he said.

Rkade is calmly certain that Fort Worth will “blow up” as a rap scene. “The good outweighs the bad, so I’m optimistic,” he said. “When you speak, words are creators, so you just speak it into existence.”

Hey, I’m kandace and I’m 23 years-old. I live in fort worth on berry.I ‘m looking for local rappers because I want to be a video model/ video dancer for music videos.If you are a rapper and you need a chick for the video let me asap.I want to start off local first.So if you are a local rapper in the area I live in let me know.I’m a songwriter too.Thanks !!

call or text me. serious only…

469-671-4508 or kandacethomas474@gmail.com