The gray-haired woman drifts in and out of reality. One moment, her mind seems sharp. “Isn’t that a perfect tree?” she says, rolling in her wheelchair through the parking lot at the nursing home where she lives. Bradford pear trees flank the pavement.

A moment later, she is beaming, telling a visitor how her mother and father are still alive and well. But they’re not. Her parents are dead. Her husband too. She has no family. If not for the volunteer guardian pushing her wheelchair, the old woman wouldn’t have much of anybody to look out for her.

A moment later, she is beaming, telling a visitor how her mother and father are still alive and well. But they’re not. Her parents are dead. Her husband too. She has no family. If not for the volunteer guardian pushing her wheelchair, the old woman wouldn’t have much of anybody to look out for her.

Volunteer guardian Sara Lee has looked after her for seven years, visiting the nursing home at least once a week and on holidays, serving as an advocate, sounding board, and friend.

“I watch very closely what’s going on with her,” Lee said. “I check her charts. I make sure she gets the care she needs. I keep an eye on her — and they know it.”

Lee volunteers at Guardianship Services Inc., a Fort Worth-based nonprofit group that represents vulnerable residents in Tarrant County to ensure they receive social services, medical care, and financial management. The nonprofit, celebrating its 25th anniversary, is legal guardian for 425 people and money manager for 245. Those numbers have been steadily increasing. More than 100 volunteers such as Lee have stepped in to help the elderly or otherwise incapacitated clients who become GSI’s legal wards.

Putting legal power over a person into a stranger’s hands is supposedly considered a last resort by the court system. On its web site, GSI says it gets involved only when “all other alternatives have been tried” and “no family member or friend is willing, able, or suitable to serve in that capacity.”

But several local families say that what began as a volunteer program to help the old and vulnerable has evolved into a close-knit alliance of probate judges, attorneys, care providers, and quasi-governmental nonprofit employees. These factions, while doing good in many cases, sometimes rip families apart without giving relatives so much as the courtesy of being present at the hearings where such decisions are made.

“The system is rigged, and the family has nowhere to turn,” said Kathie Seidel, one of a handful of local residents who accuse the probate court and GSI of removing loved ones from their homes unnecessarily.

The residents describe being replaced as guardians in court hearings without being given a chance to defend themselves — and then being required to put up $10,000 bonds in order to be allowed to appeal the decision. Overturning a court’s decision on guardianship can become a maze of dead ends. Families don’t know where to turn, other than to legislators who might change the laws — and that’s been a slow-moving ship.

“It is true there is no statewide agency with oversight over guardianship programs,” said Lesley Ondrechen, director of the Texas Guardianship Certification program. “They are accountable to the court that appointed them.”

“It is true there is no statewide agency with oversight over guardianship programs,” said Lesley Ondrechen, director of the Texas Guardianship Certification program. “They are accountable to the court that appointed them.”

The families believe the system involves too-cozy relationships between judges, attorneys, caseworkers, and others and is rife with intimidation and retaliatory behavior designed to shut out families that might get in the way.

Attorneys donate money to the election campaigns of probate judges who assign those same attorneys to guardianship cases. Attorneys also donate money to GSI, which in turn shepherds clients to nursing homes and other facilities that want to keep their beds filled. The nonprofit’s funding is based on its number of clients. Its board of directors is mostly composed of attorneys and has included nursing home representatives in the past.

“Guardianship Services is supposed to be a service,” said Debby Valdez, a San Antonio-based activist who is helping families fight back through legislative action. “When it becomes a business, it’s no longer about the ward, it’s about the money.”

Those who take part in the system say it runs well and provides valuable assistance. “This is not a perfect world, but we do guardianship as well as anybody, better than anybody, and we want people to know we do it right, and we do it according to the law,” GSI marketing director Marnie Stites said.

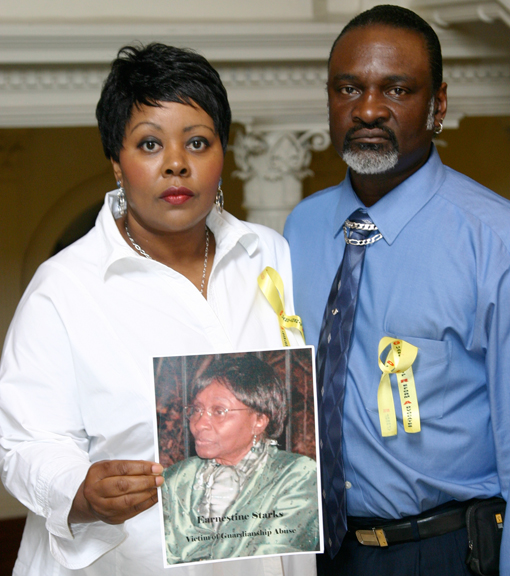

Efforts to expose the system’s flaws and build support for reforms fell on deaf ears in the past, but that might be changing. Four North Texas families traveled to Austin last week to testify at a Texas Senate interim hearing along with other families from around the state. They told their stories to a committee led by Sen. Jane Nelson of Flower Mound, describing secret hearings and retaliation from court-appointed guardians using family members as pawns in power struggles. They lamented an overall lack of regulation.

Senators appeared surprised and concerned about what’s happening in some guardianship cases.

“It’s not making sense,” said Dallas’ Sen. Royce West.

Earnestine Starks was independent most of her life, working two and sometimes three jobs at a time as a single mom raising five children in Fort Worth. After her kids were grown, Starks continued living alone well into old age, even after she began suffering delusions. Medication helped, but she didn’t think she needed it and sometimes refused to take it. An anonymous caller notified Adult Protective Services about Starks. The agency, part of the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, evaluated her and determined she needed an assisted-living situation.

Her daughter, Sharon Richardson, became her legal guardian, and Starks settled into a facility. But Richardson began questioning the quality of care her mother was receiving. A struggle of wills among Richardson and nursing staff and caseworkers ensued.

“Before I started complaining about the nursing home, the court investigator thought I was fully qualified to be my mother’s guardian,” she said.

In summer 2009, Richardson signed out her mother for an eight-hour release one day and took her to a relative’s funeral. When they returned, Richardson said, Starks resisted going back into the nursing home and began slapping at her daughter. Richardson said she tried to restrain her raging mother, and they both toppled over in front of several nursing home staffers.

Richardson considered it an unfortunate incident, a grieving mother lashing out at the world. The nursing staff saw it differently.

Within a couple of hours, the Fort Worth probate court that oversees the guardianship program sprang to action. Judge Pat Ferchill removed Richardson as legal guardian without consulting her or hearing her side. GSI was appointed as her mother’s new caretaker. The document granting the change in guardianship noted that family members did not contest the decision but didn’t mention they weren’t given an opportunity to do so.

“I wanted to testify and dispute that,” Richardson said. “She’s my mother, I love her, and I wanted to be her guardian. My father was killed when I was 5. My mother raised her kids as a widow and always took care of us. She was there for us. I owe it to her to be there for her.”

A year later, Richardson and her brothers and sisters are still battling a guardianship system that leaves little room for second-guessing. Nursing home staff threatened them with arrest for trespassing during one of their visits. They say they’ve been treated like annoyances by the judge, court investigators, court-appointed attorneys, and GSI caseworkers. When they fight back, it makes things worse.

“It gives you an ill feeling,” said Starks’ son, Gerald Banks. “It’s frustrating to try to hold it all in.”

The low point came when their mother was moved to a different facility without their knowledge.

“They kept my mom for a week and refused to tell us where she was,” Richardson said. “They told us if we undermine them in any way or do anything they didn’t like they would prevent us from seeing our mother. They would not tell us where she was until we agreed to those terms.”

Richardson’s attempts to talk to the judge went nowhere — Ferchill wouldn’t return her calls, and when she went to visit him in person, he wouldn’t see her, she said. Her siblings became split — some wanted to follow GSI’s directions and toe the line. Others wanted to fight to get their mother back.

Richardson’s attempts to talk to the judge went nowhere — Ferchill wouldn’t return her calls, and when she went to visit him in person, he wouldn’t see her, she said. Her siblings became split — some wanted to follow GSI’s directions and toe the line. Others wanted to fight to get their mother back.

“I’ve been overwhelmed trying to figure out what’s the right thing to do,” Richardson said. “I don’t want anything worse to happen to her.”

A staffer in Ferchill’s court, who asked for anonymity, said the court lost confidence in Richardson as a guardian after the scrap with her mother. Also, she wasn’t providing information needed to get her mother qualified for Medicaid and was insisting on moving her mother out of the facility against her doctor’s recommendations.

Richardson could have contacted the court and possibly worked within the system to re-establish her guardianship, the source said. Otherwise, she could appeal the court’s decision.

Several local families have complained of being removed as guardians in ex-parte hearings — that is, hearings where not all interested parties are in attendance. The families call them “secret hearings” because the judge makes a decision without listening to their side of the story. The senators in Austin appeared to be most appalled at the idea of families being shut out of such hearings.

In Richardson’s case, however, an ex-parte hearing wasn’t used. Ferchill merely rescinded his previous order designating Richardson as guardian. “It’s a fine sort of legal distinction, but within 30 days any judge can rescind an order and say there’s been a mistake,” the source said.

Ex-parte hearings have been used in questionable situations in other parts of the state, the source said, but Tarrant County’s probate courts use them in a tiny fraction of cases — only a handful of times in 30 years. In the Starks case, guardianship was changed quietly and without Richardson’s involvement because the judge worried she might whisk away her mother if she knew.

Richardson’s ordeal is reminiscent of one previously covered by Fort Worth Weekly (“Saving Katia,” July 2, 2008). Kathie Seidel adopted a Russian orphan in 1993, and 4-year-old Greg lit up the house. Wanting Greg to have a sibling, Seidel adopted another Russian orphan, this time a girl named Katia.

Katia spent her first eight years living in a Russian orphanage. She arrived in Fort Worth with a host of problems, including autism and mild brain damage. And she was explosive, diagnosed with attachment disorder, a behavioral difficulty common among neglected and abused infants. Such children can swing back and forth between kindness and sometimes-dangerous cruelty.

Seidel was prepared. She had taught emotionally disturbed students for years and earned a master’s degree in special education. “Katia came to the right place when she came to me,” she said.

The ensuing years were a roller coaster. Seidel spent her savings on assorted treatments for Katia and noticed marked improvement. Katia took nutrition supplements under a doctor’s guidance and participated in a program at the Texas Christian University Institute of Child Development.

Her rages tapered off. She was maturing. But in September 2006, Katia erupted at home, threatened her mother and brother, and was taken to a local hospital for examination, medicine, and, Seidel assumed, a quick release.

Katia, however, was upset and told hospital staff she argued frequently with her mother. She admitted she might physically harm her family, and she said she wanted to live somewhere else. Those comments prompted a discussion among hospital staffers and representatives of the probate court and Mental Health and Mental Retardation of Tarrant County.

Ferchill assigned a court investigator to study the situation. Afterward, the court removed Seidel as Katia’s guardian without inviting her to the hearing.

Patti Gearhart Turner is a former court investigator and guardianship attorney in Ferchill’s court and a former GSI board member. Now an assistant dean of student affairs at Texas Wesleyan University School of Law, Turner said ex-parte hearings are allowable in certain situations under the probate code.

“If you need to remove a guardian who is perceived to have placed the ward in eminent harm, there are provisions in the code that allow you to act quickly,” she said.

Ex-parte hearings are used sparingly and only in emergencies, she said. She recalled a past situation where someone needed emergency medical care and the guardian couldn’t be found, so an ex-parte hearing was held to name a new guardian.

“In a situation like that the court needs to act very quickly … and get treatment for the ward,” she said.

The Texas probate code empowers judges to remove guardians for any number of reasons and without notice. None of the reasons appeared to apply to Seidel. But the judge appointed Fort Worth attorney Robert Gieb to represent Katia temporarily until the court could determine what to do with her.

Seidel supplied the court with documents and expert testimony describing how Katia’s condition had improved with treatments. Attachment disorder specialist Karyn Purvis, who had worked with Katia, sent a letter to Gieb explaining the girl’s condition and how damaging it could be to remove Katia from her family and put her in an institution.

Gieb didn’t respond. A court investigator advised the court to remove the girl from her home. Gieb agreed. The judge assigned GSI as the new guardian. And Katia was enrolled at Cimarron, a Lewisville institution with a poor record for treating clients.

More than three years later, Seidel is still battling the court and GSI over her daughter’s welfare. She feels like she’s up against a system that doesn’t appreciate squeaky wheels, a system that has the law on its side. Seidel is allowed to see her daughter once a month for a short, supervised visit. A court staffer said Katia is improved, happy, well-adjusted, working, and independent. Seidel, however, has received numerous letters from Katia saying she misses her family and wants to come home.

“Everything Katia is doing now, she did while she was at home with me,” Seidel said.

GSI and the courts won’t discuss specific clients or guardianship cases, citing confidentiality requirements. But GSI Executive Director Colleen Colton touts the Tarrant County system as a solid, efficient method of protecting the elderly and vulnerable from harm or exploitation. Family members’ wishes are considered, but the clients’ needs come first, she said.

“The judges in Tarrant County have set up kind of a unique system,” she said. “Theoretically, there are court-initiated guardianships all over the state of Texas. But in Tarrant County they’ve taken that seriously to the point that they’ve hired court investigators, assistant court investigators, and court visitors that go out to the house.”

“The judges in Tarrant County have set up kind of a unique system,” she said. “Theoretically, there are court-initiated guardianships all over the state of Texas. But in Tarrant County they’ve taken that seriously to the point that they’ve hired court investigators, assistant court investigators, and court visitors that go out to the house.”

The law requires ad litem attorneys to be appointed to represent clients.

Donors to Ferchill’s election campaign are almost exclusively attorneys — and that’s the case with many judges. Some of these attorneys are given ad litem appointments. Meanwhile, GSI’s private donors include both judges and attorneys.

Seidel views this mutual back-scratching as unethical and proof of collusion.

Both Colton and Turner pointed out that family members can appeal any court decision.

But appeals are expensive, and many families can’t afford them. Seidel found out just how expensive when she filed a motion in Ferchill’s court and was told to provide a $10,000 security bond to cover probable court costs.

“It was effective — it kept us out of court,” she said.

An Arlington couple who tried to challenge Ferchill’s decision to remove them as their child’s guardian ran into the same requirement for a $10,000 security bond. The couple asked for anonymity for fear they’ll make their situation worse by speaking publicly. “My wife and I have been living a nightmare,” the child’s father said.

The Ferchill staffer said judges don’t “sell their soul” for contributions. Acknowledging that some contributors do get ad litem appointments, the staffer said that happens because the attorneys are experienced in guardianship matters.

Katia remained at Cimarron for 10 months before being moved to a group home. Later, when the Weekly asked her ad litem attorney to explain why Katia was sent to the facility despite its low ratings and despite her doctors’ wishes, the attorney said Katia “wasn’t there that long.”

Court investigators and GSI caseworkers are certified by the state. Anyone who disagrees with their actions can complain, Colton said.

“If they think that we’re abusing our certification, they can go to the Guardian Certification Board,” she said. “There are several different parties that can investigate. It’s not a closed system. It’s all public record.”

Seidel tried that method as well. She’d never been told about the certification board, but once she discovered it she filed a complaint against GSI caseworkers assigned to Katia, saying they were not caring for her properly.

The Texas Guardianship Certification Program was created in 2006 to make sure court-appointed guardians are competent and qualified. The program currently oversees 327 licensed guardians. But few family members are aware of the certification board. GSI doesn’t tell them, and the certification board doesn’t advertise itself. Since its creation, the board has received only two complaints from family members. One was dismissed because the board didn’t have jurisdiction. The other came from Seidel.

Ondrechen, the director, said complainants are allowed to speak to the board members during the complaint process. Members then make a decision. Colton said both sides get a fair hearing, and the board rules without bias.

“We had to go down there and appear, and the complainant filed a stack that big, and we hired an attorney and filed a stack that big, and they took hours and hours going over the case and interviewing the people complaining,” Colton said.

Seidel recalled things differently. Prior to the scheduled hearing, she was recuperating from knee replacement surgery and asked to reschedule. The board denied her request. Seidel asked to be allowed to participate by phone and was again denied. So, despite Seidel’s physical problems, her son, Greg, drove her to Austin.

“We sat and waited a long time in the lobby, which was hard for me to do because of my surgery,” Seidel said. “Then we went into a room where Lesley Ondrechen and other people were talking. I was told the complaint was dismissed. I did not get to talk to that board at all.”

Some board members participated by phone, even though Seidel had been denied the same opportunity. Ondrechen said the committee met in closed session because of the confidential nature of the case. After the closed session, the committee moved to an open meeting, and Seidel was given an opportunity to speak. Then the committee “recommended that the complaint be dismissed,” Ondrechen said.

Seidel was so upset she left.

“It’s rigged,” she said. “Family guardians have no place to turn.”

Colton said the board ruled against Seidel because “it was not a valid complaint.”

Several local families saw an opportunity to grab attention for their cause when a state Senate committee met in Austin last week to discuss guardianship issues. Instances of guardianship abuse are common across the country. Critics lament unethical attorneys and court investigators who are supposed to protect vulnerable residents but, on occasion, exploit them instead.

The hearing was supposed to focus on guardianship programs overseen by state agencies. Sen. Nelson made it clear beforehand that guest speakers were to stay on subject.

Tarrant County’s guardian system, overseen by the courts, didn’t really match the topic, so the families knew they might make the drive to Austin for the 9 a.m. workday session and still not be heard. At best, they expected to get three minutes each to talk. Tired of being blocked at every turn by judges, caseworkers, and professional guardians, they figured it was worth the gamble.

To the families’ relief, the senators listened. Most were given far longer than three minutes. Afterward, the senators continued talking to them for more than an hour.

“Rest assured, I know we have some real concerns that need to be fixed,” Nelson said.

She encouraged the families to keep working within the system for reform.

After hearing Richardson’s story, Sen. Bob Deuell of Greenville said the committee should consider legislation that requires family members to be present in hearings that strip them of guardianship.

“She should have had the opportunity …” he began.

“… to have her day in court,” Nelson chimed in, finishing her colleague’s sentence.

Pushing for similar reforms nationwide is the National Association to Stop Guardianship Abuse (NASGA), an Indiana-based nonprofit group working to get a federal response to guardianship problems caused by self-policing courts and programs.

Pushing for similar reforms nationwide is the National Association to Stop Guardianship Abuse (NASGA), an Indiana-based nonprofit group working to get a federal response to guardianship problems caused by self-policing courts and programs.

“Each state is different, and each county has their own procedure, so the only answer is federal,” said Sylvia Rudek, a NASGA board member. “There is no due process. They have ex-parte hearings. There are no civil rights — that’s what makes it federal.”

Richardson, Seidel, and the other families who made the long haul to Austin were thrilled when they left the Senate chambers.

“That was better than anything that’s ever happened,” Seidel said, beaming. “I can’t understand why it’s taken so long for Sen. Nelson and the others to be aware of this, because we’ve been notifying them for years.”

Judge Steve M. King, one of two probate judges in Tarrant County, said the guardianship program contains checks and balances. Disgruntled family members can file motions for new hearings or appeal court decisions, he said, but some choose to seek redress by lobbying lawmakers.

“We’ve got legislative committees that are amenable to these one-sided complaints,” he said. “The judges can’t be advocates.”

King serves on a national association of probate judges and has seen abuses in the system. He sees people living longer while also owning more property and money — and who thus are more apt to be taken advantage of by others.

“This is why the courts are tasked with monitoring guardianships,” he said.

Counties establish their own guardianship programs, and Fort Worth’s is considered a model because of its investigators and social workers trained in guardianship issues and its zeal in monitoring cases, according to many within the local and statewide guardianship systems.

King said that, nationally, when courts are struggling under heavy caseloads and insufficient funding, poor decisions can result. But he said the local system is among the best in the country.

“Texas is way ahead of many other states in their ability to monitor and their actual monitoring,” he said.

Colton, GSI’s longtime leader, said she understands that family members sometimes feel they have been unjustly removed as guardians. She has plenty of faith in Tarrant County’s probate judges and their methods but acknowledged that some cases are difficult and require judgment calls that can be controversial.

She is considering establishing an outreach program to help families understand how to deal with the system. She recalled instances in the past when families have volunteered with GSI, completed training courses, and re-established themselves as legal guardians, she said.

The people who have the most problems are those who clash with caseworkers, nursing staff, and seemingly everyone else involved in the system, rather than working to establish a rapport, she said.

“They don’t understand the way we operate,” Colton said. “You just need to kind of show us you are on the same page and you are not trying to cause trouble at the nursing home.”

Volunteer guardians are trained to deal with nursing staff, follow protocol, approach the right people for the right solutions, and fight for their clients in a manner that, in GSI’s opinion, ultimately works out best for the ward.

“I’d like to provide support for family members serving as guardians,” she said. “Sometimes the family members may be removed even though they’re trying hard — they just don’t understand how it works. A lot of it is learning how to do things — not just pitching a hissy fit but to know the ropes.”

Family members say they’ve tried that route unsuccessfully. But it’s tough to be cooperative with a program that removes them as guardians in secret hearings, and it’s hard not to pitch fits when someone they love is being taken from them by strangers who don’t seem interested in hearing their side of the story.

“We’re going to come up with ways to put transparency in this system,” Seidel said.

Key word……Organized Crime…. don’t trust especially any and all of Tarrant County….go outside of the state….. it will take the good Lord to clean house….

they said it couldn’t be done….and THAT being the matter of people against CPS a very similar ABOMINATION to these kangaroo courts known as the probate court.

They are suing them and winning and it all starts with the 14th amendment as in “due process”.

Then from there it progresses to false witness,which translates into LYING then to perjury etc.

Then we have the matter of the STATE INTERFERING etc etc-

and some are going it all alone pro se as well and that’s due to the nationwide SHORTAGE OF ATTYS willing to go and play on the federal level which is where the action MUST TAKE PLACE as these court appointees and others have no immunity.

it will end when THEY suffer finacial loss and HOPEFULLY financial ruin.

Key word……Organized Crime…. don’t trust especially any and all of this county….go outside of the state….. it will take the good Lord to clean house….

Key word……Organized Crime…. don’t trust especially any and all of this county….go outside of the state….. it will take the good Lord to clean house.

Key word……Organized Crime…. don’t trust especially any and all ….go outside of the state….. it will take the good Lord to clean house.

and will somebody make the move on WHY do we have a Constitution WHEN WE CANNOT ACCESS THE COURTS when rights are violated ?

costs and fees,complexity of rules and regulations–WHY IS THIS ?

OUR federal system should be as accessible as traffic court and OPEN TO ALL without begging attornys for help. “THEY” do not want cases on the federal level DUE TO FEES AND COST and TIME LOST from other quick cases.

absolutely NO ONE IS CONCERNED with the outright and easily verifiable violation of the 14th amendment via these probate courts and their hearings,never mind this secret stuff–how many backroom deals go on anyway PLACING our handicapped adults wherever THEY WANT like they were a commodity or baggage to be warehoused ?

and you don’t/didn’t KNOW A THING until AFTER THE FACT as in when YOU went to your esteemed “hearing”–that’s HOW i found out and then going through court’s record came across the aaction of the AAL GAL faxing to MY ATTY,the judge and THE SOCIAL WORKER of the facility HER answerDENIAL–WEEKS BEFORE THE HEARING…

and the OUTRIGHT LIBEL she spewed at the hearing and my then atty DOING NOTHING ?? gee,think something went on prior to the hearing ???

PEOPLE ! WAKE UP AND REFUSE TO TOLERATE THIS ANYMORE.

removing our adult aged handicapped children WITHOUT due process IS and always WAS A VIOLATION of your rights.

removing our adult aged handicapped children BASED ON SCATOLOGY and outright LIES and again without due process id a violation of OUR RIGHTS,

become familair with the slow but steady progression of successful cases AGAINST CPS which uses the EXACT SAME UNCONSTITUTIONAL FORMAT and remain optimistic.

SOMEONE in TX will step out and start the ball rolling against these unlawful probate courts and their unlawful HABITUAL PRACTICES.

I have read all kinds of stories on the probate courts of Tarrant county taking loved ones away, and not taking care of ,but just for the money. I don’t need any more stories’ I need help.

My wife of 20 yrs has been taking by the court of King. And her court appointed lawyer is on the side of APS .

We go to court 1-15-2015 or they go its a closed court, no one but judge and attorney’s.

Help me bring my wife back home.