Wednesday, March 17, 10 a.m.: In the basement of Van Cliburn Hall downtown, musicians from the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra are chatting with one another and practicing scales or snatches of music. Only woodwind, brass, and timpani players, are here, since this is a sectional rehearsal. The facility’s handsome rehearsal space is brilliantly lit to compensate for the overcast skies outside.

At 10, dressed in a casual shirt and slacks, Maestro Miguel Harth-Bedoya, as expected, strides into the hall. But surprisingly, he has the principal string players with him. They’re here because Harth-Bedoya wants to talk about the way the orchestra tunes its instruments.

At 10, dressed in a casual shirt and slacks, Maestro Miguel Harth-Bedoya, as expected, strides into the hall. But surprisingly, he has the principal string players with him. They’re here because Harth-Bedoya wants to talk about the way the orchestra tunes its instruments.

You know the drill: The oboist plays the note A above middle C, and the rest of the musicians use that note to make sure their instruments are properly pitched. It goes on several times in any concert, though few audience members give it a thought, whether they’re casual fans or die-hard classical music lovers.

I’m spending the next few days here with the orchestra, and I was expecting some revelatory introductory remarks from Harth-Bedoya about the piece that they’re here to rehearse, Sibelius’ Fifth Symphony, a work he has never performed with FWSO. Instead, he spends the next 45 minutes discussing tuning-related issues with the musicians.

Of course, I find this stuff fascinating, but I’m more of a music geek than the average person, and even I wonder if this is a bit excessive. How many As should the oboe give for tuning? Should there be fewer As during the shorter Friday concerts? One musician asks whether the conductor is doing this because he’s heard the orchestra going off-pitch. Harth-Bedoya says no, they just need to set procedures because the different sections of the orchestra aren’t in tune with each other.

“It’s a work in progress,” he says.

Eventually, the assembled musicians decide that the oboe will give three As to tune the orchestra: the first to tune the stringed instruments exclusively, the second to tune the brass, and the last one for the woodwinds. The maestro also advises the musicians not to talk while others are tuning. Only after this is resolved does Harth-Bedoya, at last, pick up his baton and start up with Sibelius.

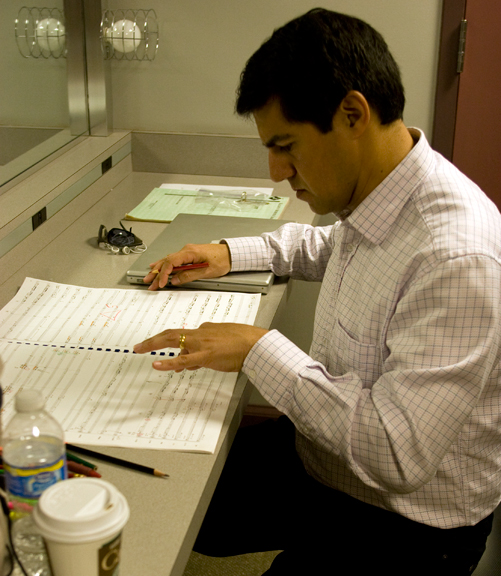

The episode is typical of Harth-Bedoya’s extremely detail-oriented approach to leading the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, something he’s done for almost 10 years. There are many different ways to conduct an orchestra rehearsal, and this is Harth-Bedoya’s way: no joking, no flowery metaphors to describe what kinds of musical effects he wants to achieve, no grand sweeping statements about what the music is supposed to mean.

He runs through the Sibelius without stopping, and while some conductors spend rehearsals constantly shouting out instructions to their musicians while they’re playing, Harth-Bedoya keeps that to a minimum. When it’s over, his instructions are highly technical in nature, much of it pertaining to how loud the orchestra should be at a given moment. “Sibelius isn’t like Mahler, where every dynamic detail is written out,” he tells the musicians. “We have to work this out.”

During his tenure as music director (a job with duties well beyond simply leading the orchestra’s performances), FWSO has reached unprecedented levels of success, putting out its own recordings for the first time, presenting works by contemporary composers to audiences who’ve never heard their music, and playing a 2008 concert at New York’s Carnegie Hall to appreciative reviews. (In The New York Times, Anthony Tommasini hailed their “assured, rich-hued, impassioned” performance of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony.) Even Harth-Bedoya’s fiercest critics freely acknowledge that he has greatly raised the orchestra’s technical standards since taking over. So what happens now?

The Peruvian conductor was hired in 2000 as the replacement for John Giordano, who had served as Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra’s music director for 27 years. Despite his youth, Harth-Bedoya offered considerable experience as a music director, having worked five years in that capacity at Oregon’s Eugene Symphony. He also had experience with a major orchestra, as the assistant conductor (and later in the more prestigious rank of associate conductor) at the resurgent Los Angeles Philharmonic.

His appointment was greeted with great fanfare, though also some skepticism from this publication. In a Fort Worth Weekly cover story (“Maestro Lite,” March 30, 2000), Leonard Eureka compared Harth-Bedoya’s previous stint as FWSO guest conductor unfavorably with those of the other maestros who had auditioned for the job, calling his Mozart “thickly textured, with neither wit nor sparkle” and his Beethoven “lacking any sense of drama or interconnectedness.” Eureka found much more to praise in the conductor’s performances of Richard Strauss, yet found him an unexpectedly awkward interview.

Yet Harth-Bedoya’s technical and musical gifts soon convinced newcomers and experts alike. In 2002 he won the Seaver/National Endowment for the Arts Conductors Award for young conductors. (Previous winners include David Robertson, who’s now the music director of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, and Alan Gilbert, current music director of the New York Philharmonic.)

Three years after his cover story, Eureka cheerfully admitted to underestimating Harth-Bedoya, hailing him as a “whiz-bang orchestra builder.” A rapturous performance of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony at FWSO’s 2004 summer festival led to curtain calls. In The Dallas Morning News, longtime classical music critic Scott Cantrell reported in 2008, “The transformation of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra continues to amaze,” and called the orchestra “worthy of its Dallas counterpart,” no small praise in light of DSO’s superior budget and fan base.

Off the podium, Harth-Bedoya is a laid-back, engaging personality. He looks scarcely older than he did 10 years ago, though now he occasionally wears glasses to read scores. He has recently taken up running for exercise. (“Always outside, never on a treadmill. Last month I was in Finland, and it was 15 degrees below zero. I still went. Running is great, because I’m alone. When I sit down, that’s when people come to me with business.”) When not attending family-related art classes and soccer games, he likes to read the poetry of Jorge Luis Borges and the novels of José Saramago, though he shows no guilt in admitting he devoured Dan Brown’s The Lost Symbol on a lengthy flight from Paris. A bit of a foodie, Harth-Bedoya often compares his work to that of a restaurant chef’s. At one point during the week he extols the taste and character of grass-fed beef and idly asks the staffers if they know where it can be bought in North Texas.

Wednesday, 2 p.m.

The afternoon rehearsal includes the string section, and the musicians are told about the new system of tuning. One of the string players applauds by tapping a bow. The full orchestra then plays the Sibelius work through.

If you’ve ever watched actors at their first reading of a new script or dancers at their first rehearsal of a work that’s unfamiliar to them, you may well be amazed at how close to performance-ready this initial run-through sounds. Of course, musicians are given their parts several weeks in advance, but an untrained ear might easily mistake this first rehearsal for a concert performance. “As a professional, you want to show up to work prepared,” says Michael Shih, the orchestra’s energetic Taiwanese-born concertmaster (a position always held by the principal first violinist, who works with the conductor to help the string section play the way the conductor wants). “You never want to be the one who inconveniences your colleagues.”

If you’ve ever watched actors at their first reading of a new script or dancers at their first rehearsal of a work that’s unfamiliar to them, you may well be amazed at how close to performance-ready this initial run-through sounds. Of course, musicians are given their parts several weeks in advance, but an untrained ear might easily mistake this first rehearsal for a concert performance. “As a professional, you want to show up to work prepared,” says Michael Shih, the orchestra’s energetic Taiwanese-born concertmaster (a position always held by the principal first violinist, who works with the conductor to help the string section play the way the conductor wants). “You never want to be the one who inconveniences your colleagues.”

After they’re done, the conversation turns to the particulars of the string parts. At one point in the second movement, Harth-Bedoya notes that the violas are too loud. “You don’t need a crescendo,” he says. “If you don’t do anything [in this part], it’ll still sound louder because the notes are going up.”

Thursday, March 18, 10 a.m.

The full orchestra moves to Bass Hall for the morning rehearsal. The Sibelius symphony is noticeably clearer and more focused than it was yesterday, but things take a radically different turn when the musicians start on one of their other pieces for this week, Jennifer Higdon’s Loco. The forbiddingly serious Sibelius work makes a huge contrast with Higdon’s antic, high-energy, brightly colored 2004 item.

Harth-Bedoya runs the orchestra all the way through it before telling them that it’s too loud, that the score is in fact dominated by dynamic markings of mezzo piano (medium soft) and mezzo forte (medium loud). The piece calls for a huge percussion section full of odd instruments, and the orchestra has to engage three extra percussionists. One of them is called on to rub two hardware-store hand sanders together starting at measure 40. Harth-Bedoya tells him to rub them louder (after ascertaining that such a thing is indeed possible), and the other musicians to line themselves up with the rhythm of the sandpaper. This is not an instruction that most orchestras hear every week.

Harth-Bedoya runs the orchestra all the way through it before telling them that it’s too loud, that the score is in fact dominated by dynamic markings of mezzo piano (medium soft) and mezzo forte (medium loud). The piece calls for a huge percussion section full of odd instruments, and the orchestra has to engage three extra percussionists. One of them is called on to rub two hardware-store hand sanders together starting at measure 40. Harth-Bedoya tells him to rub them louder (after ascertaining that such a thing is indeed possible), and the other musicians to line themselves up with the rhythm of the sandpaper. This is not an instruction that most orchestras hear every week.

One of the keys to Harth-Bedoya’s revitalization of FWSO has been his emphasis on programming music by living composers. The music director is a passionate advocate for their cause: “Beethoven was once outrageously new,” he says. “Without composers, [the orchestra] has nothing to play. We have to keep in touch with what’s going on. Without [continuity], music ceases to live.” To that end, Harth-Bedoya spends much of his time listening to CDs of new works and reading scores, as well as scouring performance programs from music schools for pieces that he doesn’t know, to follow up on later.

Higdon is the latest to take part in FWSO’s composer-in-residence program, following the likes of Behzad Ranjbaran, Kevin Puts, and Gabriela Frank. (A few weeks after this concert, Higdon will be named as the winner of the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for music.) Loco’s presence on the program is part of a deliberate strategy adopted by the music director and the orchestra to sell the public on new works by pairing them with established staples of the repertoire. The contemporary music isn’t merely of academic interest. I remember a 2005 concert of some beautiful, shiver-inducing works by Argentinian composer Osvaldo Golijov that made me feel privileged that this city was home to an orchestra willing to play this music and able to play it so well.

The rehearsal is interrupted briefly when Higdon, 48, walks in, to the musicians’ applause (expressed by stamping their feet, since their hands are busy with their instruments). A brisk presence in a conservative pantsuit, Higdon’s unforced good cheer brightens the hall. She sits in the orchestra seats to listen to the rehearsal, offering advice only when Harth-Bedoya asks for it, as in an instance when there’s some confusion over when the timpani are supposed to make an entrance. She’s evidently pleased by the overall performance; as the rehearsal ends, her brassy voice booms across the auditorium: “Fantastic!”

She and Harth-Bedoya go back some years. They both studied at the distinguished Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where she played flute in a student orchestra that he conducted in 1989. “It’s been amazing watching his career grow,” she says. Now a professor at Curtis, she spends a significant amount of time traveling around the country to advise ensembles that are performing her music. She’s full of praise for the acoustics at Bass Hall (“I hear a lot of halls. This one is first-rate.”) as well as Harth-Bedoya.

“He knows what’s out there in the music world,” she says of his advocacy of contemporary music. “Not all conductors are like that.” She’s no less impressed with his feel for her music in particular. “It’s like he’s reading my mind. I don’t have to say very much.”

Thursday, 2 p.m.

Ye Sijing, a 17-year-old Chinese pianist taking part in a Juilliard School pre-college program, is the soloist for Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1. A first-prize winner at the 2008 Gina Bachauer Youth Competition, she’s here through Harth-Bedoya’s connections — yet another testament to the music director’s networking skills. She runs through the piece this afternoon with little inspiration, but during the performances, she’ll play with fire and character. Even in the run-throughs, her technique is formidable. “Oh, my, she’s going fast,” I think during the work’s frenetic climax. The orchestra musicians are impressed, too — more stamping of feet.

The afternoon rehearsal also takes up Higdon’s blue cathedral, a celebrated piece with a more serious intent than Loco’s. It was composed for a commencement ceremony at Curtis, and while such works tend to be festive and boisterous, hers is reflective and ethereal. Harth-Bedoya informs the orchestra that blue cathedral was written partly in memory of the composer’s brother, a clarinetist who died young, which is why much of the piece can be understood as a dialogue between the prominent clarinet part and the other instruments. It’s the only time this week that Harth-Bedoya mentions the composer’s intentions.

The afternoon rehearsal also takes up Higdon’s blue cathedral, a celebrated piece with a more serious intent than Loco’s. It was composed for a commencement ceremony at Curtis, and while such works tend to be festive and boisterous, hers is reflective and ethereal. Harth-Bedoya informs the orchestra that blue cathedral was written partly in memory of the composer’s brother, a clarinetist who died young, which is why much of the piece can be understood as a dialogue between the prominent clarinet part and the other instruments. It’s the only time this week that Harth-Bedoya mentions the composer’s intentions.

The mood in rehearsal lightens quickly when orchestra librarian Douglas Adams arrives to demonstrate how the musicians should play the Chinese reflex bells, which provide a gently shimmering backdrop during the latter half of the piece. The instruments, which look like metallic balls, are played by holding them in the palm of one’s hand and shaking them from side to side. The musicians can’t help but notice that the hand motion looks incredibly masturbatory. Adams seems to realize this as he counsels them to maintain a firm grip: “You don’t want your little balls falling out and rolling around on the floor.” The laughter crescendos.

Friday, March 19, 8:30 a.m.

Financially, orchestras are essentially 19th-century institutions trying to survive in an age when music of all kinds is more widely available than ever. The great orchestras of Europe tend to be heavily government- subsidized, but public money is much scarcer in America. Here an orchestra must raise funds through subscriptions, donations, and ticket sales. A music director who focuses solely on music while ignoring fund-raising and public relations will have a hard time. It’s better if he can present a friendly face to his audience.

Financially, orchestras are essentially 19th-century institutions trying to survive in an age when music of all kinds is more widely available than ever. The great orchestras of Europe tend to be heavily government- subsidized, but public money is much scarcer in America. Here an orchestra must raise funds through subscriptions, donations, and ticket sales. A music director who focuses solely on music while ignoring fund-raising and public relations will have a hard time. It’s better if he can present a friendly face to his audience.

That’s why Harth-Bedoya is in the green room this morning at Bass Hall entertaining the symphony’s donors. They’ll be in the gallery to hear the morning rehearsal, but first they meet Higdon and hear from Harth-Bedoya about highlights of the upcoming 2010-2011 season. These longtime supporters make for a friendly audience. Terry Ryan, a 25-year season ticket holder, hails the music director for having “brought the orchestra to greatness.”

Robin Millman is newer to the club, having recently moved to Fort Worth from Boston, where she regularly heard the legendary Boston Symphony Orchestra. “You never know what you’re going to get when you move to a new town,” she says. “I was so happy to find this amazing orchestra.”

Like many nonprofit organizations, the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra has had to adjust to the adverse economic climate. A few weeks after this session with the donors, I asked the symphony board’s president/CEO Ann Koonsman how she’s coping with the downturn.

“Valium,” she joked.

She didn’t sugarcoat the symphony’s financial situation, calling the previous two quarters among the toughest she’s ever seen. After several years of budget surpluses in the mid-2000s, the orchestra ran up a deficit of $372,000 last year. To make up the shortfall, the orchestra had to spend its entire contingency fund, built from the previous years’ surpluses. The orchestra also had to call off its planned performances of Mahler symphonies this summer, since those complex works require expensive additional musicians and rehearsals. Instead, FWSO will play Baroque music at their festival, which calls for smaller numbers of musicians and can be done relatively cheaply.

Koonsman showed me sales figures: Single ticket sales are up $78,000, but subscription sales are down by $129,000. “People have less leisure time, and more of them are attending concerts on the spur of the moment,” she noted. “What that means for us is that we have to sell events rather than the season. That requires a bigger marketing budget.”

Back in the green room, Harth-Bedoya exudes an easy charm as he answers the donors’ questions about the music they’re going to hear. He excels in this relaxed, informal setting. When Higdon admits that she doesn’t hear the notes of her compositions in her head and needs a piano to work them out, Harth-Bedoya draws a laugh from the donors by breaking out his iPhone and showing an app with a small keyboard on it. Tap one of the keys, and the phone sounds the corresponding note. (There’s also a metronome built in.) “I don’t have perfect pitch,” he admits. “This comes in very handy.”

Monday, April 5, 2 p.m.

“If you play the way you’re supposed to play, it doesn’t matter if you’re happy or unhappy,” says Harth-Bedoya, responding to questions about morale among the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra musicians.

It’s impossible to gauge job satisfaction at FWSO without polling every single musician, and the orchestra’s board doesn’t ask the musicians for feedback. (“We tend to think that [the musicians] are here because they want to be here,” said Koonsman.)

Some of the musicians I spoke to were indeed delighted with Harth-Bedoya’s leadership. Timpanist Edward Stephan, who’s leaving for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra next season, praised the music director’s energy and reliability. “There’s an enthusiasm here that’s unique to orchestras. Miguel lets us play the way we know how,” he said.

Some of the musicians I spoke to were indeed delighted with Harth-Bedoya’s leadership. Timpanist Edward Stephan, who’s leaving for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra next season, praised the music director’s energy and reliability. “There’s an enthusiasm here that’s unique to orchestras. Miguel lets us play the way we know how,” he said.

Principal clarinetist Ana Victoria Luperi had the same orchestra teacher as Harth-Bedoya at the Curtis Institute. “The reason any musician joins an orchestra is the music director,” she said, citing Harth-Bedoya as a major factor in her decision to come to Fort Worth. (She also cited the climate, her last job being with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra.) “This orchestra is getting better with him,” she said.

Still, a number of musicians raised complaints about Harth-Bedoya’s leadership and his relations with them. For excellent reasons, most of them did not want me to use their names. A music director can ask that a musician be removed entirely from the orchestra or demoted from principal to section musician. (When an orchestral composition calls for a solo part for any instrument, it’s the principal of that instrument section who plays the solo. Demotion to section player would represent a significant financial hit for a musician, though some would feel more pain over the loss of opportunity to play solos.) There is an appeals process, but many musicians would rather spare themselves the stress.

Principal trumpeter Steve Weger was willing to undergo that process and also to let me use his name. The 28-year veteran of the orchestra was surprised in August 2008 to receive an official letter from Harth-Bedoya citing problems with Weger’s pitch and intonation. This was the first step in the process of terminating his employment.

“I’m 66 years old,” said Weger. “I thought, ‘Why do I want to fight?’ But eventually I thought this was so wrong that I had to stand up.” In a further blow to his pride, the letter arrived shortly before the orchestra was to perform Stravinsky’s Petrouchka, a ballet that features the trumpet prominently. Weger had reason to think that the issue at hand wasn’t his pitch or intonation, since he had played eight years under Harth-Bedoya’s baton with no indications of any problems. However, he is at a loss to explain why he was targeted.

Essentially, Weger had to audition for his job all over again. He received a second letter of warning, then a third, which triggered the appeals process. Nine of his fellow FWSO musicians formed a peer review committee, Harth-Bedoya chose a list of works that the orchestra had played recently, and Weger was allowed to play the trumpet parts from his choice of the works on the list. Saving his job required affirmative votes from seven of the nine committee members. Earlier this year, the committee decided to retain him.

It didn’t end there, though. Rather than congratulate Weger on winning his appeal, the music director instead used a subsequent rehearsal as the forum to deliver a prepared statement declaring his unwillingness to continue as music director for an orchestra that didn’t agree with him. Some orchestra members briefly thought that he had resigned.

I didn’t have a chance to ask Harth-Bedoya about the specifics of the process, but he framed the rehearsal incident in this way: “Let’s say I want you to write something for me, but I have to take your computer away. You still have to do your work. How do you do that? You have to allow everybody to do what they do. I had to remind [the orchestra] of that.”

Weger, meanwhile, is planning to retire on his own terms. He wishes that it had all been handled differently. Harth-Bedoya, he said, “could have talked to me. He could have asked, ‘When are you thinking of leaving?’ ”

Another allegation about Harth-Bedoya that’s on the record is an article from the October 2005 newsletter of the Dallas-Fort Worth Professional Musicians Association, in which union president Ray Hair stated that when the union was considering rejecting a new contract that had been offered by orchestra management, Harth-Bedoya used a rehearsal to try to pressure the musicians into accepting the deal by waving an unsigned, undated letter of resignation. (“What a power trip,” Hair editorialized at the time.) The union eventually voted to reject that contract and negotiated one with terms they viewed as more favorable.

Hair refused to comment for this article, citing the union’s upcoming negotiations for a new contract to replace the expiring one that was signed in 2005. Harth-Bedoya flatly denies ever threatening to resign, and when I ask why he didn’t take legal action over such a wild allegation if it were false, he says, “It’s a waste of time. What does legal action have to do with music making?” He calls this story “third-hand information … written by people who were not at those events.” However, multiple orchestra musicians who were present in 2005 confirmed Hair’s story.

I ask Harth-Bedoya how he deals with musicians who, rightly or wrongly, aren’t happy with their job, and he sternly quotes the first part of the orchestra’s mission statement (“to provide symphonic performances at the highest level of artistic excellence”). With sarcasm creeping into his voice, he says, “Some orchestras may have as their mission, ‘We are here to come together in great friendship and be happy and play as best we can.’ That’s fine, but that’s not our mission.”

Friday, March 19, 8 p.m.

Before his performances of each piece on the program, Harth-Bedoya addresses the audience via microphone. Some conductors prefer to preserve their mystique as silent vessels for the music, but Harth-Bedoya would rather help the crowd understand what they’re about to hear. He brings Higdon up on stage to talk about her works. He describes the landscape of Finland in the early spring, with its barren expanses and sudden glimmers of light, as something for the audience to imagine while listening to the Sibelius symphony. He has not communicated a similar sentiment to his musicians. (When a snowstorm blows into Fort Worth on Saturday, he’ll tell the audience that night that it fits with the mood of the piece.)

Composed between 1914 and 1916, Sibelius’ Fifth is unusual both in structure and texture. The Finnish composer’s popularity crested in the decades before his death in 1957, but since then his fame has receded somewhat. This is perhaps why Bass Hall is only about two-thirds full; a few weeks later, a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony will sell out.

The crowd that does turn up hears an intelligent, purposeful performance, though it’s not overwhelming or transcendent. The playing is technically masterful, notably in a passage in the first movement with a bassoon solo (strongly played by principal bassoonist Kevin Hall) over a lengthy passage of soft but lightning-quick sixteenth notes played by the strings. This passage has received special attention during the week, and the strings carry it off without any smudging or smearing, despite the fact that the musicians are spread from one wing of the stage to the other. Shih had told me earlier, “It always amazes me that these musicians can sit at opposite ends of the stage and still play in perfect unison.”

The crowd that does turn up hears an intelligent, purposeful performance, though it’s not overwhelming or transcendent. The playing is technically masterful, notably in a passage in the first movement with a bassoon solo (strongly played by principal bassoonist Kevin Hall) over a lengthy passage of soft but lightning-quick sixteenth notes played by the strings. This passage has received special attention during the week, and the strings carry it off without any smudging or smearing, despite the fact that the musicians are spread from one wing of the stage to the other. Shih had told me earlier, “It always amazes me that these musicians can sit at opposite ends of the stage and still play in perfect unison.”

The orchestra takes a back seat to Ye Sijing in the Liszt concerto, accompanying her dutifully. (FWSO tends to expend less energy on concertos, even under the baton of guest conductors.) Higdon’s Loco charms the audience, but it’s blue cathedral that receives the evening’s best performance, achieving the reverent yet colorful hush that the piece calls for.

Afterward, Harth-Bedoya says he thinks the Higdon performances went very well, while allowing that the Sibelius could have gone better. Pressed for specifics, he says, “You can’t think of that. It’s like playing a game and thinking, ‘I should have scored.’ ” Whether it’s due to his temperament or his busy work schedule, he doesn’t do postmortems, and he probably won’t revisit this performance until the next time he conducts Sibelius’ Fifth. “Performances come out of a particular time, where you are physically and mentally,” he says. “You can’t duplicate it.”

When I ask what he wants to accomplish in the next five years or so, Harth-Bedoya talks mostly about promoting the orchestra’s work in the community and online. As far as improving the orchestra musically, all he says is, “We have to play better. It’s simple.”

Of course, he was similarly vague when Leonard Eureka asked him the same question 10 years ago. The vagueness fooled Eureka into underestimating the new music director (as Eureka himself later admitted), but it didn’t prevent FWSO from reaching the rarefied heights of Carnegie Hall.

Many acclaimed performing artists find that it suits them to keep doing whatever they’ve been doing rather than thinking too deeply about the reasons for their success. Still, it’s curious that when I ask Harth-Bedoya about what he’d do if he left the FWSO post, his answers are much clearer.

The need for stability for his family is his first concern, he says. Beyond that, he muses, “Not being the music director of an orchestra might be a nice change. I’ve been doing this for almost 25 years, so why not?” He also describes going full time into academia as a possibility; he already teaches classes on conducting at TCU.

All in all, Harth-Bedoya doesn’t talk about his feelings very much. He agrees quickly when I ask him whether the Carnegie Hall concert was the proudest achievement of his Fort Worth tenure, but just as quickly he moves on to another subject.

He talks about music in a matter-of-fact way, never evincing strong likes or dislikes for individual pieces or composers. One of his signature achievements is the Caminos del Inka series of concerts, promoting both historical and contemporary South American music. (It’s now a foundation, with other orchestras performing this body of music, led by Harth-Bedoya as well as other conductors.) Clearly he cares a great deal about this, yet my question about his reaction to being a Spanish-speaking conductor in a city with such a heavy Latino population doesn’t seem to interest him. “It may make a difference in terms of marketing or positioning, but music is a universal language,” he says.

All this testifies to qualities that both his supporters and detractors see in him: the desire for caution and control — a valuable trait in a conductor, but one that, like most other things, can be taken too far.

At 41, Harth-Bedoya is still a young man by the standards of the conducting world. There seems little doubt that the orchestra’s board of directors will work to extend his contract, which runs out in July 2011. Koonsman doesn’t stint on praising him as a musician, calling him one of the world’s great conductors and saying she has “immense confidence in his ability to grow.”

The danger, however, is something that Cantrell picked up on in a recent article. He applauded Harth-Bedoya’s track record of working “miracles,” then wrote, “[Harth-Bedoya] now rarely plumbs beneath the surface of mainstream repertory. He’s in danger of becoming the Andrew Litton of Fort Worth: the gifted, mediagenic conductor who comes in with great promise but doesn’t grow.” It would be a sad fate if FWSO were to turn into one of those orchestras that offers up technically perfect but emotionally sterile music.

Ultimately, no one knows whether Harth-Bedoya’s extraordinary talents will help take Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra to even greater heights or whether the same qualities that made him successful to this point will prevent him from achieving more. The only answers we’ll get are in the performances at Bass Hall over the next few years.