New York and Los Angeles are convenient home bases for actors seeking work, but hardly the perfect fit for a West Texas fellow with a fondness for horses, cowboy hats, and cold beers shared with plainspoken, friendly folks.

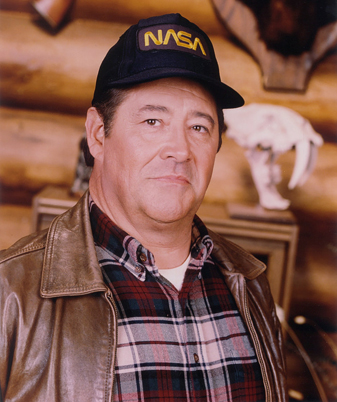

Actor Barry Corbin spent years in both of those imposing cities during his well-traveled life. In 1990, however, he got a call that brought him to North Texas, where he’s put down some of the deepest roots he’s ever planted.

Actor Barry Corbin spent years in both of those imposing cities during his well-traveled life. In 1990, however, he got a call that brought him to North Texas, where he’s put down some of the deepest roots he’s ever planted.

The call came from a grown daughter he’d never known he had. He met her, got to know her and her children, and eventually bought all of them a 14-acre property near I-30 and Eastchase Parkway. Fort Worth has been home ever since — the longest he’s ever lived in one house. With his 70th birthday approaching, he’s content to grow old here — especially since, with a major international airport nearby, he can still jet away to movie sets in far corners of the world, when work calls.

But time keeps changing, and Corbin, who has always rolled with the punches of his uncertain profession, is weaving and bobbing again. The actor known for his roles in Lonesome Dove, Northern Exposure, Dallas, WarGames, and, more recently, No Country For Old Men, has found there aren’t as many calls as there used to be for his considerable skills, meaty face, and Texas drawl. Money’s tight, his grandkids are grown, and he can no longer afford an 8,000-square-foot house and acreage. It’s been on the market for a while with no takers.

This year, with debts mounting, he declared bankruptcy, mostly to buy time while he tries to recoup his investment on the land. And he and his daughter and grandkids are in the process of moving into much more modest digs, a row of three small homes his daughter owns in Handley. It will be another family compound, with room for a couple of horses — but no swimming pool, no guest house, no private screening rooms.

Corbin’s not worried though. He’s lived an actor’s vagabond and topsy-turvy existence ever since he put Lubbock in his rearview mirror as a young man and headed to New York to become a stage actor. He’s been in hit movies; he’s acted in stinkers. He’s been flush; he’s been broke. He doesn’t expect or even seek firm footing. He rides waves. Ride one a while, he said, and jump to the next. His cowboy philosophy doesn’t lend itself to huge emotional highs or devastating lows. Problems work themselves out. Or they don’t.

“I never did care anything about money,” he said. “I told my kids, money is the least important thing in the world unless you don’t have enough or you have too much. If you get too much, you start worrying about it. If you don’t have enough, it’s hard to keep the basic necessities. In the middle, money’s not important. That’s the way I’ve always felt, which is probably why I’m in the shape I am today. But I don’t regret it.”

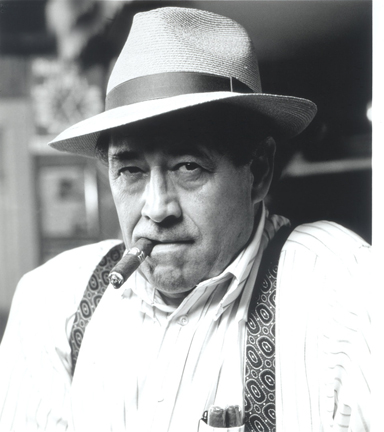

Sitting down to discuss money issues is about as appealing to Corbin as raking a rusty spur across both shins. It took finagling (read: pleading, through his attorney) to get the actor to invite a Fort Worth Weekly reporter to his home on a recent afternoon. At the designated hour, I showed up expecting a cursory interview with a begrudging profile subject. Instead, the interview included feeding horses Smitty and Odie, watching two of Corbin’s recent movies, ordering pizza, and then adjourning to a nearby bar where he hangs out on evenings when he’s in town. When I left at midnight, he was still knocking back a curious combination of cranberry juice, water, and Shiner Bock drafts, chatting up employees, and playing video poker.

Sitting down to discuss money issues is about as appealing to Corbin as raking a rusty spur across both shins. It took finagling (read: pleading, through his attorney) to get the actor to invite a Fort Worth Weekly reporter to his home on a recent afternoon. At the designated hour, I showed up expecting a cursory interview with a begrudging profile subject. Instead, the interview included feeding horses Smitty and Odie, watching two of Corbin’s recent movies, ordering pizza, and then adjourning to a nearby bar where he hangs out on evenings when he’s in town. When I left at midnight, he was still knocking back a curious combination of cranberry juice, water, and Shiner Bock drafts, chatting up employees, and playing video poker.

Born in Lamesa near Lubbock, Corbin loved horses and the rural life like many kids his age. He was fascinated with Hollywood cowboys at Saturday movie matinees, but equally struck by the works of Shakespeare. By first grade, he’d already decided his life’s path: He would be an actor.

West Texas in the 1940s was isolated. Corbin spent summers on his grandfather’s farm and developed a love of horses. At the same time, he lost himself in books. His mother was a schoolteacher; his father’s career included being a lawyer, state senator, judge, and school principal with an appreciation of Shakespeare.

“I read the plays, and the language was fascinating to me,” Corbin said. “Same with the King James Bible. I’m not a religious person, but it’s a great collection of literature. I’ve always had an affinity for those things. I can’t explain it.”

Reading didn’t make him a sterling student. Corbin disliked regimentation and eschewed studies that held no interest for him. When a person plans his career by age 7, his focus of study narrows. Corbin didn’t care about math or science but would spend hours poring over the works of Constantin Stanislavski and Anton Chekhov to absorb theories on acting and playwriting.

As a kid he wrote and produced no-budget neighborhood plays. In high school, he joined a theater group — and the Future Farmers of America. In his spare time, he hung around older kids in the theater department at Texas Tech University and watched rehearsals for fun.

“I was an odd kid,” he said. “I’m an odd old man.”

In the decades since then, he’s figured out that those quirks made him fit right in with his profession.

“All the good actors I know don’t have a choice,” he said. “They have a calling. That’s how it was with me. My mother discouraged me. My father discouraged me. My college professor said, ‘You’ve got to have something to fall back on.’ I said, ‘If I have something to fall back on, then I’ll fall back. If I don’t have anything, then I’ve got to do it.’ ”

After high school he dabbled in higher education at Texas Tech but wasn’t interested in much beyond acting, horses, girls, and cold beverages. At Tech he sometimes napped in a particularly fetching spot. A dumpster behind a greenhouse was often stuffed with discarded flowers, making a soft, aromatic mattress for catnaps — at least until a garbage truck came by and emptied the load with Corbin inside. The incident secured his campus reputation as an entertaining sort.

For spending money, Corbin chopped cotton and roughnecked on oil rigs during school breaks. A Lubbock oilman imported a ballet master from Lithuania because he had a daughter who wanted to learn ballet. Corbin joined the class, learned to pirouette, and eventually played the Prince in Swan Lake — probably the only male teenager in Lubbock at the time willing to don tights for a ballet recital.

In 1960, when he was 21, Corbin left college and joined the Marines.

“I got my draft notice because my grades weren’t so good,” he said. “I didn’t want to go into the Army. I thought about the Navy, but you had to join for four years.”

The Marine Corps won out because they offered a two-year stint. Still, two years at Camp Pendleton in California seemed like a lifetime to Corbin. The military wasn’t a good fit for a rangy, pirouetting, theatrical, Shakespearean, dumpster-sleeping cowboy.

The Marine Corps won out because they offered a two-year stint. Still, two years at Camp Pendleton in California seemed like a lifetime to Corbin. The military wasn’t a good fit for a rangy, pirouetting, theatrical, Shakespearean, dumpster-sleeping cowboy.

“I was not very good at it,” he said. “I’m a team player up to a point, but mainly I want to make my own decisions. What they try to do in basic training is break you down to your essence and then build a Marine. With me it didn’t work. I became more and more of a pacifist and got out as quick as I could.”

Corbin returned to Texas, acted in regional theater, then moved to Boulder, Colo., to act in a Shakespeare festival. After the summer run ended, he decided either to try New York and the stage or head to Hollywood and the movies. He flipped a coin; New York won.

But it took a while to get there. Broke, he lived for a time in Chicago doing manual labor and acting in community theater at night. He made it to New York a few years later and stayed at the YMCA for the first three weeks. Acting gigs were hard to find.

“People didn’t know what to think of it,” Corbin said. “My dad said, ‘That’s a good hobby, but you can’t make a living doing that.’ When I went to New York, I think he thought I was holding up 7-Elevens.”

The Big Apple became home base. He got married, had a son, settled down. But working typically meant traveling to smaller cities to perform in dinner theaters and summer stock. Lots of times he slept in his station wagon. His first marriage floundered in 1970. He married again in 1976.

For a fearless guy with a desire to roam, the life wasn’t bad. Still isn’t.

“I’m a gypsy,” he said. “I always have a bag packed. If they call me and say I’ve got to be in New Zealand tomorrow, I grab my bag and go. It drives some people crazy. It’s probably why I haven’t been able to stay married.”

A blackout during the sweltering summer of 1977 in New York prompted his next adventure.

“It was miserable,” he said. “Garbage piled up. Just awful. I told my wife at the time, ‘Pack up, we’re going to California.’ ”

He had no regrets.

“I didn’t work Broadway very much, and the only way to make money in theater is on Broadway,” he said. “But [acting] is very satisfying. It’s a lot of fun. By this time I was 37 years old, and I thought it was time to go to California and see if I really had the goods.”

“I didn’t work Broadway very much, and the only way to make money in theater is on Broadway,” he said. “But [acting] is very satisfying. It’s a lot of fun. By this time I was 37 years old, and I thought it was time to go to California and see if I really had the goods.”

Hollywood greeted him with a huge yawn.

Corbin had no screen experience and no agent. In Hollywood in 1977, Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind were the big movies. At the time, Corbin was a stage actor who felt at home in Shakespearean costumes and fake mustaches.

“It was a rude awakening,” he said. “Nobody wanted to talk to me.”

A New York acquaintance recommended an agent. Corbin visited the agency, but the staff “didn’t see the possibility of me doing anything.”

So he spent the next two years writing plays for National Public Radio. He expanded one of those radio plays into a full-length stage play, which debuted at a Los Angeles theater and stirred up interest from Universal Studios. In 1979, he found an agent, who went to see the play. Corbin had given himself a role, and the agent liked his acting more than his playwriting. A few weeks later, the agent sent him to audition for Urban Cowboy. Corbin wore his typical Texas garb — boots, jeans, cowboy hat.

“I went in and read a couple of scenes,” he said. “My agent called after a week and a half and said, ‘They made an offer.’ He told me what [amount] it was and I said, ‘Is that good?’ And he said, ‘No, but it’s good enough for the first one.’ I said OK.”

Before the part was his, however, he had to meet John Travolta. Corbin recognized the actor’s name from his Welcome Back, Kotter TV show and the recent hit Saturday Night Fever. Corbin was being considered for the role of Uncle Bob. It was a substantial part in a movie with a rising star. It sounded too good to be true.

“I met John, and he said, ‘We’re going to have a lot of fun with this.’ I said, ‘I guess we are,’ but I still didn’t know if I had the part for sure,” Corbin said. “I didn’t really know anything about making movies. They flew me to Houston for rehearsals and handed me money. Cash. I thought that was my pay. It was just per diem.”

Corbin spent three months in Houston, living in an apartment near Gilley’s nightclub with his wife and newborn son. “Uncle Bob” led to other juicy parts in 1979. Corbin did a hilarious turn as a rich gambler in the Clint Eastwood flick Any Which Way You Can, and portrayed a warden in Stir Crazy with Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder. All three movies came out in 1980 and were moneymakers. Corbin was suddenly a hot commodity.

In his first scene filmed for the Eastwood movie, Corbin’s character, Zack, drives a car following the Eastwood character, Philo Beddoe, as he jogs along a road. The script called for Beddoe to run toward the car while a frightened Zack locks the door. Beddoe would then smash the car window with his fist and yank Zack out of the driver’s seat. But Corbin, who had barely met Eastwood, was so startled to see such a big movie star that he forgot to lock the door.

“He came running up and did this” — Corbin curled his lip in a typical Clint Eastwood sneer. “I thought, man, that’s Clint Eastwood. I started to open the door.”

“He came running up and did this” — Corbin curled his lip in a typical Clint Eastwood sneer. “I thought, man, that’s Clint Eastwood. I started to open the door.”

Eastwood smashed the window. Corbin, worried that he had temporarily gone out of character, insisted they reshoot the scene. He was unaware of Eastwood’s penchant for quick moviemaking.

“I said, ‘We got to retake that, we got to redo it, you have to put the window back because I was not “in the moment,” ’ ” Corbin recalled, laughing. “Clint said, ‘It’ll be fine.’ They used that first take.”

Eastwood is unlike most of the characters he has portrayed in films, Corbin said. He recalled the star as being consistently easygoing and down to earth.

Pryor was different. Stir Crazy was shot at a maximum-security prison, and Corbin remembered Pryor as being quiet and isolated.

“Gene Wilder would go out and play basketball with killers and robbers and shove them out of the way while playing,” Corbin said. “But Richard didn’t want anything to do with them. He was afraid of them, which probably showed good judgment on his part.”

Corbin feared being pigeonholed and sought a variety of roles and media. He played a sheriff on the TV series Dallas from 1979 to 1984. During that time he also acted in another Eastwood picture (Honkytonk Man), two Burt Reynolds movies (The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas and The Man Who Loved Women), and a cutting-edge flick about computer hacking (WarGames). He found lucrative jobs throughout the 1980s, culminating in one of his favorite movie experiences — the TV miniseries Lonesome Dove in 1989. It was his first real Western. Producers cast him as dim-bulb deputy Roscoe Brown. The drawl came naturally.

He followed that with another TV series in 1990, portraying former astronaut Maurice Minnifield in Northern Exposure. The show lasted five years and earned Corbin an Emmy nomination in 1993. After a career of small stage appearances and supporting roles, he’d finally found a leading role on a hit show and was riding high. Little did he know he was about to rush headlong into a human drama far more riveting than his TV role.

During his seasons of Northern Exposure fame, Corbin got word that a woman in Texas was claiming to be his daughter.

His agent called, freaked out. “A woman called from Texas and — you don’t have to call her back — I’m just passing the message on, but she says she’s your daughter,” Corbin recalled the agent saying.

He thought back to his college years and to a young woman, an actress at Texas Tech, with whom he’d had a fling. One day she told him she was pregnant, and Corbin told her he’d marry her. But a week later she said she’d been mistaken — she wasn’t pregnant. In actuality, the young actress’ father, a rich oil executive, sent her to San Antonio to complete her pregnancy and put the baby up for adoption.

He thought back to his college years and to a young woman, an actress at Texas Tech, with whom he’d had a fling. One day she told him she was pregnant, and Corbin told her he’d marry her. But a week later she said she’d been mistaken — she wasn’t pregnant. In actuality, the young actress’ father, a rich oil executive, sent her to San Antonio to complete her pregnancy and put the baby up for adoption.

Corbin thought about that timeline and the pregnancy scare. “You know, the interesting thing about this is, it’s probably true — give me her phone number,” he told his agent. “I called her and talked to her for about an hour. We’ve talked every day since.

“She came out to visit [in Seattle, where Northern Exposure was filmed] and we pretty much hit it off,” he said. “We went roping together.”

His daughter is Shannon Ross. She’d been adopted 26 years earlier and grew up in Arlington. In 1990, she was married with two children, including Jordan, a toddler who battled cerebral palsy and other ailments. Wondering if genetics played a part in Jordan’s condition, she hired a detective to track down her birth mother. The mother agreed to talk and delivered a bombshell: Ross’ birth father was Corbin, the famous actor — and he wasn’t even aware of her existence.

“She said they were in a play together, and it was the 1960s, and it was one of the first times they ever went out,” Ross said.

As it turned out, finding her birth parents didn’t provide Ross with any clues about Jordan’s health problems. But it did end up changing her life, and Corbin’s.

At the time, Corbin was getting divorced from his second wife. His wife got the couple’s California home. Corbin ended up with a pickup, a trailer, four horses, joint custody of their two sons, and not much else other than a solid acting resumé. He was thrilled to discover he had a daughter and grandkids.

Ross was pregnant and also splitting up with her spouse. Corbin was recovering from a serious injury — Smitty had fallen on him during cutting practice and broken his foot, ankle, and leg.

So Corbin came up with an idea. He would buy a house with land near Arlington, and Shannon and her children could live with him.

“I came here and looked at several houses and settled on this one because of the location,” Corbin said. “It’s centrally located between Fort Worth and Dallas. Jordan used to go to Scottish Rite Hospital in Dallas and [Cook] Children’s Hospital in Fort Worth. He had to be close to both places.” Corbin bought the land in 1994 from former Texas Rangers manager Bobby Valentine.

The property was also close to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport with its nonstop flights to Los Angeles, New York, and anywhere else that might lure a gypsy actor. Ross helped look after the livestock when Corbin was gone.

The first time they had talked on the phone, Corbin told Ross he was branding cattle. She was thrilled. “I thought, ‘Oh, you ride horses!’ ” she remembered. “I thought it was just pretend, that he did it in the movies. I didn’t know he did it for real.”

Her adoptive parents didn’t care much for horses, but Ross kept one stabled near her Arlington home for years. Likewise, her parents weren’t thrilled about Ross moving in with her birth father.

“My mom had a hard time, but she came around when she realized that, had it not been for my dad, I couldn’t have been able to be home with my kids while they grew up,” Ross said. “At first she was real leery, thought he was some Hollywood guy coming in trying to get publicity. You’ve only got to know him for a minute to know he’s not like that at all.”

Best of all, the arrangement allowed Ross to spend time with Jordan, who manages his physical problems well.

“Jordan practically lived at Cook’s and Scottish Rite all his life until they kicked him out a couple of years ago when he turned 18,” Ross said. With some of the financial pressure taken off her by Corbin’s offer of a home, “I could sit there with him and do stuff that a lot of people don’t have an opportunity to do.”

In recent years, however, roles have grown sparse for Corbin, and the financial high from his Northern Exposure days is long gone. The grandchildren are grown, and the big house is more than Corbin and Ross need or want.

They decided to sell his property and move into the rent houses that Ross had bought in Handley.

“It’s not only the mortgage and the taxes, it’s also the maintenance of the place,” he said. “If I were making the money I used to make, it wouldn’t be a problem. But I’m not making it now.

Corbin’s bankruptcy attorney, St. Clair Newbern III, said Corbin and Ross have been good for each other.

“We all need somebody in our lives to be there when we need them, and since she showed up in Barry’s life, she has been that person for him,” Newbern said. “She strikes me as somebody who is genuinely interested in taking care of her daddy.”

Corbin said he’s looking forward to moving to more modest digs. The three adjoining houses in Handley have a combined three acres, providing open space for the horses but close proximity for the tight-knit family. The third house will be occupied by Ross’ two youngest children, including Jordan, who are now grown.

“As long as we’re together, it’s OK,” Ross said. “The houses are not as big, which is good. We don’t need that. What I was worried about is [that] we would be spread out all over the place. We do stuff together every day.”

Corbin is sitting by a fire in his living room when Ross comes downstairs on her way to run errands. She lives in the main part of the house, while Corbin and his girlfriend, Barbara, live in a guesthouse.

Father and daughter exchange “I love you’s” as she leaves. Corbin loads a dip of Copenhagen in his lip, zips up his jacket, and heads out back into a cold and windy drizzle to feed his horses. He’s as gentle and caring with them as he is with his daughter. He leans in close and whispers something to Smitty. The cutting horse is now 25 and gets special food because of his bad teeth.

Corbin no longer keeps cattle and bison as he once did. He donated his favorite longhorn, Sam Houston, to the Fort Worth Herd several years ago. And at the encouragement of the late Sue McCafferty, founder of the North Fort Worth Historical Society, Corbin offered his services free to narrate Wall Street of the West, a documentary on the Stockyards.

“It was a story that needed to be told,” he said.

Graciousness doesn’t necessarily show up in a bank balance. Corbin stills gets job offers, but mostly from small, independent films.

“I’m working a lot, but they’re not paying what they used to pay,” he said. “The studios are going for these big blockbusters; there’s not much in there for me. I’ve been doing these ultra-low-budget SAG [Screen Actors Guild] pictures. Essentially, they feed you lunch and promise you some money if they make money in the back end.”

But he’s made some fine movies. Last year’s That Evening Sun with Corbin, veteran actor Hal Holbrook, and Mia Wasikowska (Alice in Wonderland) earned high praise from critics and film festivals. Corbin’s part in the Academy Award-winning No Country For Old Men was a plum, but it didn’t pull him out of the financial doldrums.

“I worked a day and a half on that,” he said. “I was paid pretty well for a day and a half, but a day and a half ain’t going to do much.”

Corbin’s career has been unusual, but his money problems are the same as everybody else’s, said Newbern, his attorney. Chapter 13 bankruptcy gives homeowners up to 60 months of protection from creditors, time to sell property and pay off debts without the threat of foreclosure.

“A lot of people are like Barry; they file because somebody is trying to foreclose on their home,” he said. “A great number of the people we represent have issues with their homes.” Corbin’s debts are not huge, Newbern said, and his situation isn’t dire. “He’s going to be fine. He’s got a nice property. He just needs the right buyer.”

Corbin could sell the property, now appraised at about $780,000, in a flash for what he owes on it, but he wants to sell for near market value to realize the equity he’s built over 16 years. The real estate market here has fared better than in other places, but buyers are still looking for fire-sale deals.

“I’m confident that when the trees leaf out in the springtime somebody is going to come along and say, ‘Oh this is just what we’re looking for,’” he said.

Realtor Terry Vernon said the main value of the property is its location. “It’s very central in the Metroplex area and has an excellent horse facility,” he said. “That’s unique inside the Fort Worth city limits.”

Vernon and Corbin have been friends for 15 years, since they met at a charity cutting horse event. Vernon describes him as honest, benevolent, and entertaining. “He’s been very generous with his time, helping to support benefits for autistic children and cancer programs,” Vernon said. “I’m proud to call him a friend.”

Corbin delayed the bankruptcy as long as possible.

“I used to think bankruptcy, the whole idea of it, was people trying to get out of paying debts,” Corbin said. “In most cases I don’t believe that anymore. It’s people trying to get the money paid back.”

Once he sells, Corbin plans to do minor renovations on his new Handley home, move his two horses there, settle down, and continue jetting around the globe to movie locales and TV studios to portray various characters, few of whom are as interesting as he is.

He’s done too much in seven decades to let bankruptcy rattle his confidence. For additional affirmation he looks no further than his grandson, a young man of high spirits despite a lifetime of physical problems. Jordan is following his granddad into acting, and the two are currently working together on an independent movie being filmed in Oklahoma. Jordan is a source of great pride to Corbin.

“He’s got one leg a little shorter than the other but if he concentrates on it you can’t tell,” Corbin said. “He’s the bravest human being I’ve ever seen. I’ve never seen anybody overcome what he’s overcome. It’s a lesson to me and makes me feel kind of humble.”

Want to read more about Barry Corbin, check out Blotch for “Barry Corbin: More For Fans”

[…] Bad; and the inimitable Corbin, who has been in tons of movies and TV shows and was featured in a Fort Worth Weekly cover story in 2010.“The movie is about a broken family that is spiraling out of control and they move to […]