Rick Wilkins stood staring at the dozens of pieces of the Scopitone, a massively tall coin-operated musical video machine from the 1950s that he had dismantled to repair.

To get to the circuit board and other failing components, he had removed the pieces and laid them out systematically by category on the floor. He had even taken photos of the wiring to make sure he could put it back right. He had stuff on little work tables and had rigged spotlights to help him see what he was doing. Now he lay down to pull out the film carousel, projecting unit, and the complete visual part of the mechanism from the entire cabinet, raised on large wooden beams for him to be able to access the mechanism’s bottom mounting bolts.

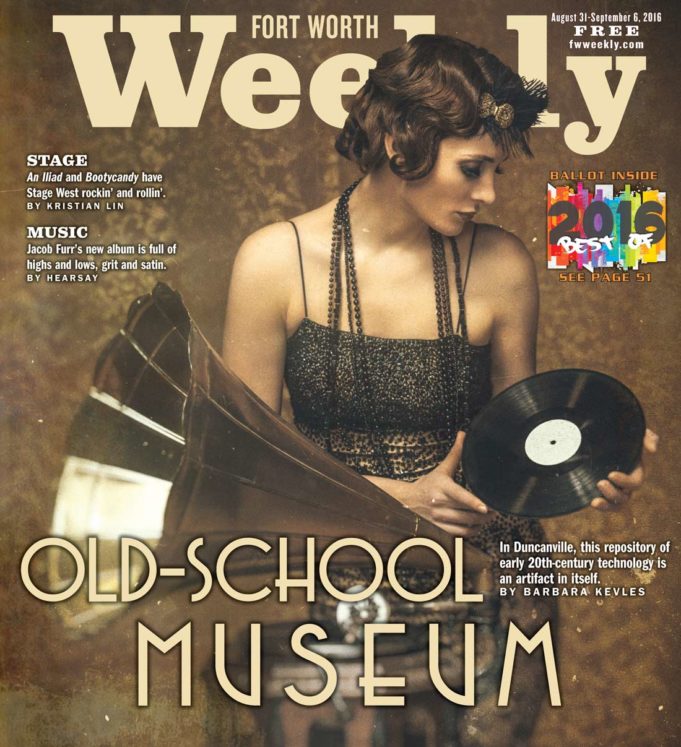

Wilkins is on a tight deadline. His boss, 94-year-old Homer DeFord, a lumber magnate who bought the Scopitone for an undisclosed sum in 1977, wants it working soon for future tours of the Olden Year Musical Museum. Founded in 1977 by DeFord out of his love of vintage technology and deep admiration for Thomas Edison, the museum is built on a family-owned city block near other family businesses in Duncanville, about a half hour drive east of Fort Worth.

The Scopitone is a tour highlight. Back in the day, bar patrons could watch their favorite bands and artists perform in color film shorts on the large screen by sliding a quarter into the coin slot. Like every other artifact in the Olden Year’s massive collection, the Scopitone still works.

Though the museum is primarily known for its hundreds of antique devices such as music boxes and hurdy-gurdys, the 16,000-square-foot red brick-and-sheet-metal cultural destination also has an enviable early 20th-century technology collection. Until now, the Olden Year’s 200 pioneer phonographs, hand-blown light bulbs, groundbreaking radios, jukeboxes, early silent and sound film machines, and post-World War II color TVs have been overlooked because of lack of museum promotion and advertisement.

Yet the museum is unique among its peers. Jim Sargent, president of the DFW Vintage Radio and Phonograph Society, a club dedicated to the preservation and restoration of antique radios and phonographs, thinks there’s nothing like it in Texas. Or anywhere else.

“The early 20th-century technology out on display at the Duncanville Museum not only rivals but surpasses the vintage machines on exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum and Smithsonian National Museum of American History.”

But given the insecure, unstable world in which we live, the museum faces new challenges.

*****

I appreciate the article by Barbara Kevles in this recent Fort Worth Weekly magazine entitled “Old School Museum”. Ms Kevles did an outstanding job of capturing the essence of a museum sitting near the center of the DFW Metroplex, a museum that is so incredible in it’s humble beginnings, and yet so carefully put together as to rival the finest museums in this country. So many historical artifacts are sitting in Duncanville that it is a shame more folks do not know of it’s existence. Hopefully Ms Kevles’ article will awaken the citizens of this part of Texas and encourage a resurgence in the historical study of these technological dinosaurs whose current versions play such a large part in our daily lives.

Jim Sargent, President Vintage Radio & Phonograph Society