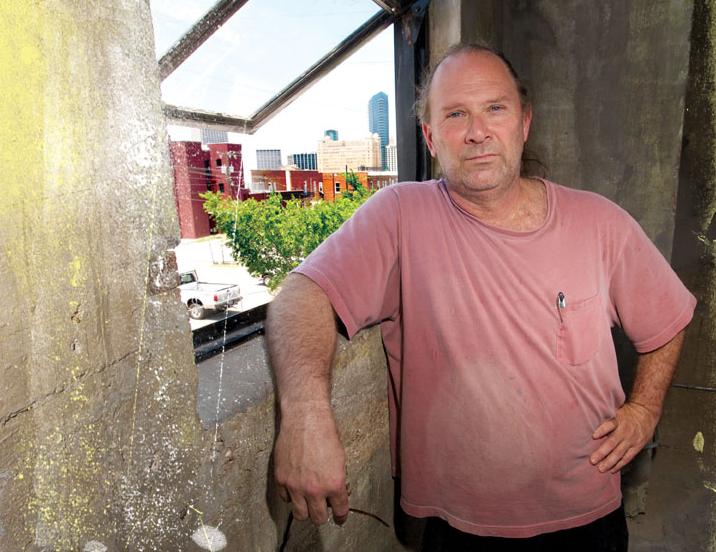

Sitting in the foyer of Fort Worth architect Bob Kelly’s office, Eddie Vanston doesn’t look like a big-time real estate developer. He’s slumped in a chair, dressed in bulky gray sweat shorts, a well-worn “Kinky Friedman for governor” t-shirt, and old work boots that look like they’ve slogged+ through years of construction sites.

The only sign that he might be involved in anything having to do with the top side of real estate development is a tape measure clipped to his waistline of his shorts. But that just makes him look like one of the guys who hangs drywall. At 53, his dishwater-blond hair is fading in the front, gathered in a long ponytail in back.

It’s not the look of a Columbia University grad who once taught English at a ritzy New York private high school. He’s meeting at the South Main Street office of Kelly, his partner in some projects on the Near Southside, because he doesn’t have his own office down there. His office is actually his car, the front passenger seat piled high with paperwork, the back seat awash with his kids’ toys.

It’s not the look of a Columbia University grad who once taught English at a ritzy New York private high school. He’s meeting at the South Main Street office of Kelly, his partner in some projects on the Near Southside, because he doesn’t have his own office down there. His office is actually his car, the front passenger seat piled high with paperwork, the back seat awash with his kids’ toys.

The unconventional look is likely a product of his unconventional approach to his business. The Dallas native (he still lives there) has been redeveloping run-down historic structures on Fort Worth’s Near Southside for more than 10 years now. Plenty of Dallas developers were lured to Cowtown’s high-end condo market in the years before the housing bust, but Vanston was here long before most of them, always working in the world of market-rate rentals.

He started by redoing the Markeen Apartments, built in 1910. Since then he has also restored the Leuda-May and LaSalle apartments, both built in the 1920s. All three were originally apartments when they opened in the early 20th century, but they had deteriorated with time.

Two of his recently completed projects can be seen through the window behind him. The Sawyer Grocery Store, built in 1909, and a former hotel (the Joyslin Building) built in 1911 have been transformed into a total of 14 apartment units. Rents range from $625 to $1,200 a month.

“I like old buildings, because the quality of the workmanship is just so much better than the new buildings we construct today,” Vanston said. “There are risks sometimes. With new construction you know what you are getting into, but in the old buildings, when you peel back the paint and get inside the walls, you often find the unexpected.

“But after all is said and done, doing the older properties at market rates is good business and good for the community,” he said. “[The Near Southside] is becoming the hottest place in Dallas-Fort Worth to do these projects. People in this area like to live in older structures that are done well, and there is a change in how folks are viewing urban living. Over time, I think this part of Fort Worth will develop into a unique community.”

Doing historic restoration in this part of town is tricky for reasons beyond what’s inside the walls. Banks are leery about providing financing, a tendency that has only been exacerbated by the recent credit crunch. And the restored buildings are often islands in a sea of vacant lots and decaying warehouses.

Then there is the perception that the urban cores of big cities are high-crime areas full of homeless people. Vanston says that’s less of a problem in this part of Fort Worth than many folks believe. As he talks, a few street people amble past the window behind him. Many of the Fort Worth homeless community gather on the corner of South Main Street and East Vickery Boulevard for day-labor jobs. Some are pushing everything they own in grocery carts.

“I’ve gotten to know some of the so-called street people, and they just are who they are,” Vanston said. “They’re not robbing and mugging people as most people think, just trying to make it in the world. They can be strange, but when you are down here all the time, like I am, or live down here, they just are part of the neighborhood.

“One of the biggest misperceptions … is that low-density neighborhoods are safer than high-density ones,” he said. “But the more people you have living in a neighborhood, the safer it is. People watch out for each other.”

Just then, Kelly Poulos, an insurance saleswoman, comes into the office to say hi to Vanston. She lived downtown for three years before moving into the Sawyer Grocery building last November.

“Oh, there are times I can look out my window, see the new Omni Hotel in the city skyline, and there might be a guy in the vacant lot across the street pissing on a wall,” Poulos said. “But we walk our dog late at night sometimes, and we have never had any trouble. I like being close to work downtown, but I also like being in a neighborhood. And that’s what [the Near Southside] is turning into, a unique place to live that is very different from the rest of Fort Worth.”

About that time, Vanston’s real estate developer spiel gets interrupted by his landlord role. A tenant from across the street comes in to tell Eddie that the coin-operated washing machine at the Joyslin Building is broken. Vanston shakes his head and gets on the phone to get a repairman out to fix it.

“This is the shit that you don’t get if you just rehab the building and sell it off to someone else,” Vanston said. “When I got into this business in Dallas, I would just fix things up, sell them, fix up another, then sell that.” But in Fort Worth, “I decided that I wanted to own stuf f. I wanted to own unique older buildings.”

f. I wanted to own unique older buildings.”

So he spends his days supervising the stripping of old wooden window frames and the buffing of hardwood floors, creating loft apartments in a 1911 warehouse with 16-foot-high ceilings and concrete walls and floors. And getting the washing machines fixed. And, in the process, helping rejuvenate a neighborhood that has been dormant for decades.

Around the corner from Vanston’s Sawyer and Joyslin buildings (Vanston swears the latter, like seemingly half the historic buildings in Fort Worth, was at one time a brothel) is a vacant building that shows how tricky the historic renovation business can be. The city built the Fort Worth Recreation Center in 1927 as a gymnasium and auditorium. After the city sold it in 1955, the building, which looks like an old airplane hangar, was converted into a factory and warehouse. An automotive parts distributor was the last to use it, moving out in the late ’90s.

Developer Tom Reynolds bought it in 1998. Reynolds’ background is also an odd mix: He is a cattle rancher and serves on the Fort Worth Stock Show board, he is a jazz guitarist performing in the Tom Reynolds Trio, and he does real estate development work, including historic renovations on the Near Southside. Reynolds wants to turn the rec center into a concert and special-events venue, going after local meeting groups and conventioneers who want catered affairs inside a unique place. Vanston and architect Kelly are interested in joining the project, though they haven’t formally partnered with Reynolds yet.

There’s nearly 17,000 square feet of open space inside under a metal-truss roof, with few interior walls carving it up. There is space for a stage in the back, and the plans might include a restaurant and balcony-level seating for good views of the stage, maybe a beer garden outside on the vacant lots next door that Reynolds also owns.

While the building is structurally sound, according to Reynolds, a lot of work would be needed to make the building functional. Much of the wooden roof decking has fallen in, street-level windows have been bricked up, and a lot of the upper-level windows are broken. Most of the original wooden flooring is long gone, and the concrete sub-flooring is damaged and pockmarked. Debris is everywhere. Historic Fort Worth Inc. has placed the rec center on its endangered places list.

Kelly, like Vanston, is a fan of preserving old buildings but also a realist. He doesn’t know whether the rec center can be saved. His firm has done some historic restoration projects, including the Ashton Hotel and Ashton Depot downtown, and he serves as chairman of the city’s urban design commission. He is also active in the South Main Property Owners Association.

“The biggest problem with historic preservation in [the Near Southside] is that [the longer] a building has stood empty, the more deterioration it has,” Kelly said. Eventually, he said, it reaches a point where “it doesn’t make any sense to throw any money into it. The rec center is getting pretty close to that. It might be structurally sound on most levels, but the cost to replace the roof and floors and windows might just be too much.”

Reynolds and Vanston think the building’s location – between the Lancaster corridor downtown and the recent developments on the Near Southside – is ideal for drawing music fans from throughout North Texas. There’s plenty of parking across the street, where the Trinity Railway Express makes its westernmost stop, at the T&P Building.

They think such a venue could keep money in Fort Worth that now heads to Dallas or to Nokia Theater in Grand Prairie every week with young concertgoers. The two men also think the renovated recreation center could accommodate big private parties for business associations. “With this incredible location, the uniqueness of this historic structure, and the hole in the Fort Worth market for large venues like this, we see this as a project that will save a historic building and provide an economic development engine in a part of the city that has great growth potential,” Reynolds said.

The problem, of course, is funding. An estimated million-dollar price tag on renovations for an uncertain business plan scares away a lot of investors.

Fort Worth does provide some property tax relief for historically designated structures, freezing taxes at pre-rehab levels for up to 10 years. But other taxing entities such as the public hospital district, Tarrant County College, and the school district don’t make similar promises, so property taxes inevitably rise as the value of the property goes up.

The federal government also offers tax breaks to repay developers for rehabilitating historic properties, but the path to that designation and therefore that funding can be long.

The first step is to get a local historic designation. Local designations don’t automatically mean that a property is added to the National Register of Historic Places, but most are, if owners request it. That national listing qualifies the restoration project for the federal historic tax credit, which repays owners for 20 percent of their restoration costs. The rules say that to qualify, the restorer must hold on to the property for five years, and owner-occupied housing doesn’t qualify. That’s part of the reason Vanston has focused on rental development.

The federal funds are administered by the National Parks Service and funneled through state agencies – in this case, the Texas Historical Commission. Last year, $91.7 million of renovation work went on in Texas, bringing in about $20 million in federal tax credits.

The city has three types of historic designations: Historic and Cultural Landmark (HCL), Highly Significant Endangered (HSE), and Demolition Delay (DD). HCL and HSE designations make it somewhat difficult to tear down a structure, though there are plenty of exceptions (for instance, when a building owner proves to the city that restoration is not financially viable). The DD designation is rather toothless. The owner of a DD building must wait 180 days after applying to the city to demolish the structure and meet with interested parties during that time span. But the meeting could take place on day 179, and if no compromise can be reached that day, demolition could begin the following day.

No properties within tax increment financing districts (TIFs) can get historic-designation tax breaks, however. TIF districts set a base level for assessments, and as values rise, the resulting additional tax dollars stay within the district to pay for infrastructure projects. But those rules may change. The legislature this year passed a bill by Fort Worth’s rookie state senator, Wendy Davis, to allow tax breaks for historic properties within TIFs. The bill will become effective in September if not vetoed by Gov. Rick Perry.

No properties within tax increment financing districts (TIFs) can get historic-designation tax breaks, however. TIF districts set a base level for assessments, and as values rise, the resulting additional tax dollars stay within the district to pay for infrastructure projects. But those rules may change. The legislature this year passed a bill by Fort Worth’s rookie state senator, Wendy Davis, to allow tax breaks for historic properties within TIFs. The bill will become effective in September if not vetoed by Gov. Rick Perry.

Fort Worth South Inc. is the nonprofit that administers the Southside TIF and promotes business in the area. Their TIF has gotten around some of the tax-break regulations by carving out some historic properties, including the rec center, from the district.

“It is part of the funding process, and when we get approved for the National Register of Historic Places and qualify for the federal tax credit, I can go to banks and show them the real numbers of how the investment will work,” Vanston said.

The Fort Worth Recreation Center has been designated as a DD by the city. So if Vanston and Reynolds come up with a restoration plan, the federal agency will probably back it with 20 percent of the cost. The developers have also had preliminary discussions with the city about getting local grant money, but the city’s $60 million budget shortfall makes it a tough sell.

“I don’t know if we can make it work without city investment, but we are exploring our options,” Reynolds said. “I am getting a little braver about this project all the time, and I think something will be happening within the next few years.”

The city is open for discussion on the matter. “If we can see how this project would affect economic development in this growing area, we will look at all the options,” said Dana Burghdoff, deputy director of the city’s Planning and Development Department. “Because when you redo historic buildings, there has to be a combination of public and private funding. But at this point we haven’t seen any finalized plans.”

The urban village concept that Fort Worth has applied in the Near Southside is based on mixing residential and retail buildings so that folks who live there can park their cars and walk to shops, cafes, and entertainment spots. But carrying out that idea involves its own challenges.

“The ultimate goal is to create a mixed-use area, where new bars and restaurants and retail will want to relocate,” Kelly said. “You can see how that is working on Magnolia Avenue, and we think it can spread as you move closer to downtown. But we have to redesign some streets and get more parking available as more people move in.”

Magnolia has become a hopping locale for restaurants and bars, and, to a lesser extent, retail shops, mostly locally owned mom-and-pop businesses in old buildings. The burgeoning Fairmount historic neighborhood just to the south of Magnolia, along with small-scale condo developments just to the north, and renovation projects like Vanston’s provide a healthy supply of customers for these businesses.

There is the problem, common in many inner-city neighborhoods in Fort Worth, of figuring out how to create parking for new residents, who usually don’t want to park on the street. Though there might be vacant lots nearby, many of those property owners don’t want to sell or pave and are just sitting on the property to see how the Near Southside revitalization plays out.

There is the problem, common in many inner-city neighborhoods in Fort Worth, of figuring out how to create parking for new residents, who usually don’t want to park on the street. Though there might be vacant lots nearby, many of those property owners don’t want to sell or pave and are just sitting on the property to see how the Near Southside revitalization plays out.

Though retail and business relocation to the area has been slow thus far, many observers expect the pace to pick up as more housing and more people arrive. Linda McHale spent $100,000 three years ago restoring a 1904-vintage house that is now the Hattie May Inn bed and breakfast. “There is a sense of community in this little pocket of Fort Worth, and as more people are living down here, families of those visiting their relatives often stay here,” McHale said.

Nelson Claytor, president of Fresnel Technologies, which makes special lenses used by surgeons, has had locations on the Near Southside for 20 years to be close to the hospitals. But in 1998 the company increased its investment in the area: It bought and restored a 1948 building on South Main Street. “We didn’t know how neat it was when we bought it,” Claytor said. “We found a tile façade under paint and kept the old tiles and replaced the broken ones with new tiles to make it match. There are problems sometimes. Dealing with utility infrastructure can be difficult. But I just like old buildings like this. The newest house I’ve ever owned was built in 1936.”

Historic renovation in the Near Southside is tougher than in some areas because of the changes the neighborhood has gone through in the past century, during which many industries moved in.

“Retail and residential buildings turned into industrial stuff,” Kelly said. “Many of those industrial companies are still here, and they are not going anywhere.” Not everyone wants to live next door to a bottling plant or a printing company. And even when the industry has moved on, it often leaves problems behind.

The Sawyer Grocery building, for instance, originally had the store downstairs and living spaces for the family upstairs. But the ground floor was eventually turned into a machine shop – a background that means it took a lot more work to bring it up to the level of comfort needed for retail businesses or offices.

Carlo Galotto likes old buildings as well, and he wanted to join that Magnolia Avenue business group. He was planning to open an Italian brew pub and restaurant this year in a building that had housed Gunn Cleaners for most of the 20th century. He planned to invest about $350,000 to start the business, but there were problems from the beginning.

A fire had gutted the 1920-built structure in January 2007, and the roof had to be replaced. Galotto bought the building in October 2008, but a contractor he hired for the renovation found problems with the new roof. It was not properly connected to the walls, and an engineer who was called in told Galotto there was a risk of roof collapse.

The city has now ruled that the building is not up to code. Galotto said that the previous owner had never filed a permit application for the roof replacement job, nor was the new roof ever inspected. Galotto is now contemplating suing the former owners, but that process could be long and expensive. “By the end of the month the city says I must begin new construction on the roof, or the building will be shut down,” Galotto said. “The city says I am responsible for everything, but they cannot explain why the construction was never permitted or inspected, and I have had a hard time getting answers or paperwork from the code compliance department.”

An engineering firm is now doing a study (which itself will cost Galotto about $6,000) of the problem. Preliminary estimates are that roof repairs could cost as much as $100,000, according to Galotto.

Code compliance officials are now investigating the permit and inspection process at the building, located at Magnolia and College avenues. In a memo sent out this week, city staffers said they were looking into Galotto’s allegations that the roof repairs caused other damage to the building and that “inspections that may have been made by the City … might have missed the poor work on the roof.”

“I love this area and would love to open this business here,” Galotto said. “I was going to use my life savings to get this started, but I don’t know if I can afford the roof costs. I don’t think the city did what they were supposed to do on this case.”

The neighborhood that started the overall Southside revitalization trend sits just south of Magnolia. The Fairmount neighborhood is now a designated historic district with very strict guidelines for restoration of homes and businesses.

Fort Worth South Inc. and Fairmount overlap by about three blocks. The larger nonprofit group has its own renovation guidelines, but in that overlap area, the more restrictive Fairmount guidelines hold sway.

But the two areas are intricately intertwined by more than those three blocks. Fairmount historic regulations have drawn a younger and more wealthy homeowner than most urban core neighborhoods, which has helped drive more businesses to Magnolia Avenue. “There are tons more restaurants and businesses now, and I would think that our designation as a historic district with strict guidelines has had a lot to do with that,” said Sue McLean, historic preservation officer with the Fairmount Neighborhood Association.

Robb See, a broker for JJ Robb Real Estate Co., which focuses primarily on housing in the Near Southside, is watching curiously to see how it all plays out. “The thing I see down here is an interesting local entrepreneurial spirit, especially on Magnolia,” he said. “But as any place becomes more popular, the prices get driven up. The small local companies get driven out sometimes.”

See said one of the problems he finds is that many homebuyers in the Fairmount neighborhood don’t stay very long. “Three to five years is about average,” See said. “Most of them are young singles and young marrieds, and when they get older and want to start a family, they might think of moving to Southlake.”

Beyond that, “Owning an old house is a lot of work, and some aren’t used to that,” he said. “It is a grim awakening when they want to put modern windows in to save on energy and find out the [historic] restrictions  say they can’t.

say they can’t.

“But it is also such a different world now than when we started our business 15 years ago,” See said. “People said we were crazy, that no one would want to live in an area like this. Now we are the hottest area of the city, because of location [close] to downtown and affordability. But if the prices for residential get out of control, the sustainable growth will taper off.”

Kevin Buchanan, a Fairmount resident and blogger on real estate development trends (forthworthology.com), sees those same trends but thinks the conflicts can be solved. “The Near Southside now has conflicting trends,” Buchanan said. “The medical community needs more office space, which drives prices up. The residents nearby want more restaurants and bars. Sometimes the needs of the residents are at odds with the medical community.”

The success on Magnolia has helped developers promote the areas farther north and east, toward downtown. Several projects are being planned by developers on or near South Main Street.

Townsite Company is planning a mixed-use development on the 10-acre site of the former Motheral printing plant and wants to restore the old Coca-Cola bottling plant as an office building. There have been environmental problems (toxins in the soil) with the old printing site, but the developers are negotiating with the city to share cleanup costs. The property was bought a few years ago by the Fort Worth school district, which later was lambasted by critics for its plans to build a school on a contaminated site.

Robert McKenzie Smith and Ken Schaumburg have done condo developments. Michael Barnard is restoring an old factory and union hall into living spaces and studios for artists. Barnard may even turn part of one building into art galleries, with space for a high-end food court or farmers’ market. Vanston is close to finishing out 15 loft apartments in the old Miller Manufacturing Building on Bryan Street.

“Magnolia is becoming a great mix of independent businesses and indie culture,” Buchanan said. “But what is crucial is to get South Main growing as a second major corridor. And what Vanston and the others are doing can make that happen.”

Buchanan has referred to Eddie Vanston as a “real estate rock star” on his blog (The two even collaborated on an April Fool’s prank this year, announcing Vanston’s intention to do a nudist housing project on the Near Southside called “Bareview,” causing numerous media inquiries.) Vanston, Buchanan said, “is one of the rare examples of someone who understands the full business experience of historic preservation. He understands how to change plumbing and air conditioning systems to modern standards. He does market-rate apartments and fills them up quickly. Eddie is proof that there is a solid business model for historic preservation.”

Paul Paine, director of Fort Worth South, also sees the development of a second corridor as crucial. He points out that the city’s plan to run a modern streetcar line down South Main Street and down Magnolia Avenue would link the two areas and promote “urban village” growth. “I think what started with the historic neighborhoods just south of us has pushed into the Magnolia area,” Paine said. “When more historic buildings get revived, I expect a lot of those vacant lots to be developed as new businesses.”

“When I started here four years ago, Magnolia was a wannabe,” Paine said. “Now we hear from people from Dallas that this is what Deep Ellum wished it could have been. We still have a lot of challenges left, but we feel we have turned the corner.”

“When I started here four years ago, Magnolia was a wannabe,” Paine said. “Now we hear from people from Dallas that this is what Deep Ellum wished it could have been. We still have a lot of challenges left, but we feel we have turned the corner.”

One of the strategies Paine and his group have used is to get as many properties as possible onto the city’s historic designation list so that developers like Vanston can take advantage of the federal tax credit. This year, Fort Worth South has asked for 60 properties to be given the DD designation, most of them private residences.

And Paine said he will be lobbying hard for the city to participate in the Fort Worth Recreation Center special-events and music venue project. “Hands down, it will be a win-win because of its location near downtown and Interstate 30,” Paine said. “It will draw people from Fort Worth but also from all over North Texas. And when we get more people coming to this area, more businesses will pop up, and more people will want to live here.”

Eddie Vanston likes to walk. Part of the reason he concentrates his redevelopment projects on the South Main corridor is that he likes to hop from building to building on foot. He is even thinking of moving his wife and two kids into the neighborhood. “I have to drive in from Dallas every day,” he said. “I don’t like cars very much.”

On a tour of his renovated buildings, we pass what was supposed to be an earlier traffic generator on the Near Southside. Its owners opened the Axis Club about five years ago on South Main near Vickery Boulevard with hopes of making it a destination music venue. But that never happened. After several changes of ownership, the club is closed. Glass from broken windows covers the sidewalk in front.

“There is a lot of uncertainty in trying to redo a part of town like this,” Vanston said. “Axis was supposed to help jump-start things. Maybe the timing wasn’t right. Maybe it was the management. We still think the rec [center] will work. But maybe us old guys are just trying to relive our youth.”

Construction dirt is flying over at the Miller Manufacturing Building, just east of South Main. Vanston is investing $1.6 million in the project, and he already has the 20 percent federal tax credit approved. “The tax credit was crucial, because I was able to go to the bank and lay this out for them, and they could see how much I was bringing to the table,” he said.

Inside, workers have completed the walls delineating 15 loft apartment units and are busy installing the modern plumbing and heating/air conditioning systems in the two-story 1910 building. The window frames are originals and have been restored, but most of the glass is new. The old window glass was frosted and full of wire mesh; replacing it will give tenants great views.

Some of the new units are true open-space lofts, while others are divided into rooms. The question for Vanston is whether Fort Worthians are ready for a living space where the kitchen and bedroom furniture are in the same room. “From the people I am showing these to, the reaction I am getting is that they like that arrangement,” Vanston said. “I tell them they can put the bed wherever they want to. Maybe string a curtain for privacy. Do whatever you want.”

He lets loose with some of his pet peeves about Fort Worth and his business. The Stockyards should be bulldozed. “This city has nothing to do with the meat-packing business any more, and everything down there is just the same old crap,” he said.

He doesn’t like the guidelines for restoring historic structures. “I know the rules, and I live with them,” he said. “But I’m not in favor of telling any property owner what they should do with their buildings. Plus, these guidelines make everything the same, and you get a very homogenized neighborhood. If you want that, go to a gated community out in the suburbs.”

And he gets a little pissed at the old guard who are holding onto vacant lots waiting to see how everything plays out. “People always make lots of excuses,” he said, “blaming the economy and the market and everything else they can think of [for not developing their real estate]. But they have been holding on to these properties for decades. We’ve proven that this part of town is doable. So these old-money people should just do it. Or sell their property to someone who will.”

Would that be you, Eddie? “No, like I’ve said, I don’t want to build anything new. Other people can do that. I just like old buildings.”

And with that he’s off to the Joyslin Building to let in a worker to fix the washing machine – another part of the Southside economic picture.

“I’ll probably have to give that guy the quarters he lost,” Vanston jokes of his tenant. “No tax credit involved in that transaction.”

I would love to talk with Mr Reynolds about the Fort Worth Recreation Building could anyone give me a contact for him

Thanks

Rick