Moni Washington enlisted in and attended the U.S. Military Prep school in 1986 as a private, and the next year, she was accepted into the United States Military Academy in West Point. She graduated in June 1991 as a second lieutenant, “the bottom-of-the-ladder starting rank for officers,” she said. Washington was one of 16 Black women to be admitted to West Point in 1987. Of those 16, only seven graduated in 1991.

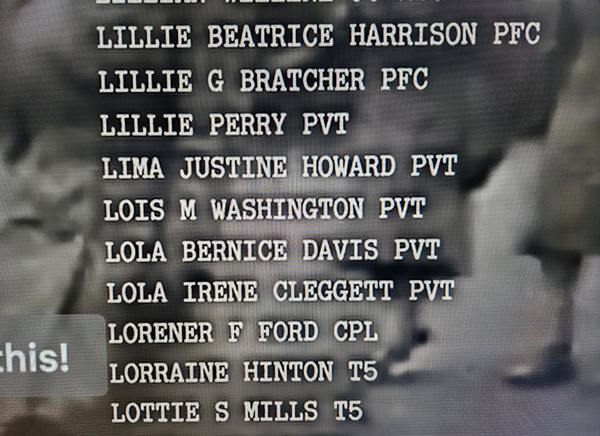

Washington thought she was the second generation in her family to serve in the Army. “It’s the family business,” she said. Both her parents served in the Army immediately before and during the Vietnam era, which officially clocks from 1954 through 1975, although U.S. forces were in the region far earlier. But it wasn’t until after her grandmother’s death in 1999 that she realized Lois M. Washington, her father’s mother, also served in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) during World War II.

Two years after Lois’ death, Washington, the executor of her grandmother’s estate, received a steamer trunk with her grandmother’s belongings. Inside were uniforms and a DD-214 –– the document from the U.S. Department of Defense that formally indicates time of military service, including the where and when. The DD-214 showed that Lois Washington was part of the legendary WAC 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, which served in a combat theater as an integral part of morale and welfare.

Tyler Perry’s World War II historical drama The Six Triple Eight (currently showing on Netflix) dramatizes events around the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, the only Black battalion of the Women’s Army Corps that served overseas in World War II. The 6888th served during combat in England and France, where they sorted thousands of letters neglected and piled up in warehouses because white male soldiers could not be freed up to attend to the sorting and delivery. In addition to overt racism and sexism, the battalion was faced with a seemingly insurmountable pile of years’ worth of both incoming and outgoing mail, much of which did not have proper addresses or even recipient or addressee full names. The group was given six months, and they finished in just 90 days.

Washington’s father, Ralph Washington, enlisted in the Army around 1948 “to get out of Chicago,” Washington said. Ralph was a medic, a licensed practical nurse (LPN) in the Nurse Corps, which was a potentially career-making opportunity for a Black soldier in those days. He served one tour of duty stationed in Korea and two tours in Vietnam before returning stateside.

Washington’s mother, Shirline “Shirley” Fox, was initially stationed at Fort McLellan, Alabama, and she was also an LPN –– the third Black female Nurse in the WAC in the late 1950s. She met Ralph when they were both working at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C. Both parents went on to continue their nursing careers outside of the Army. Shirline left the Army around 1962 due to her newly married status. Ralph remained on active duty and retired in 1981 after more than 35 years of service. Washington joined the Army “out of respect” for her parents.

Photo courtesy of Moni Washington

“They were my biggest cheerleaders,” she said. “I was amazed at their service. I loved watching them put their uniforms on — starched nursing whites. Nursing and the military was the family business.”

Women have volunteered for military service probably since the American Revolutionary War in 1775, although formal documentation of women’s military service dates to the American Civil War. But it was only in the last century that the WAC gave credence, purpose, and organization to their service. Six months before women received formal military status, the first contingents of female soldiers arrived in North Africa and England. After official incorporation, three WAC units joined the British Southeast Asia Command in New Delhi, India, in October 1943. That year, WAC platoons arrived in Italy and Cairo, Egypt. In January 1944, WAC units arrived in New Caledonia and Sydney, Australia. Of course, these were only white women.

The WAC wasn’t even considered an official branch of the U.S. Armed Services until after World War II. The Women’s Armed Services Integration Act in 1948 enabled women to serve as permanent members of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and the newly founded Air Force. However, the Act limited the number of women who could serve to 2% of the forces in each branch. The WAC was eventually folded into all units of the U.S. Army (with the exception of combat forces) in 1972, just after Shirley’s forced retirement from the WAC.

*****

In her mother’s WAC, they had different uniforms because “they weren’t really in the Army,” Washington said. At the time Shirley served, very few women served in the Army, much less Black women.

Washington’s grandmother Lois (Ralph’s mother) was, as far as she knew, a civil servant with a respectable job in a Chicago post office. Washington was born in 1968, and Grandma Lois crocheted a lot of her clothes. Washington remembers taking Lois to the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center in Chicago for medical and hospital services but assumed that Lois was connected to care there because she was the widow of a veteran.

As the executor of Lois’ will, Washington has some family heirlooms, including pottery her grandmother made and an armoire that houses some of Lois’ fancy gold-rimmed China. But it wasn’t until two years after her grandmother’s death that she realized Lois served two tours of duty as a private in the WAC during World War II.

“She never told us anything” about her time in the Army, Washington said. “My brother is 13 years older than me –– someone had to know something.”

Washington recently spoke to her brother, and he had no information about her service, either.

“He said she did not entertain questions at all,” Washington said.

As it turns out, Lois’ story is part of Perry’s The Six Triple Eight, although many of the supporting cast of actresses play amalgamations of different real-life women for brevity and also for continuity and interest in the storyline.

Moni Washington

Grandma Lois was a bit of a mystery. Her race was in dispute –– she called herself Black, but her death certificate lists an Irish-named parent. She was also allegedly part Cherokee, but she didn’t like to talk about that, either.

“When I asked about my heritage in 1984, she said in the 1900s it was worse to be Irish and Cherokee than Black,” Washington said. Lois “spent 50 years changing” her race, and it stuck.

“I am mulatto,” Washington remembers Lois saying. And there was no information superhighway back then to put us on a technological leash. “We can’t doctor anything these days,” Washington said with a laugh.

In the 1940s, she passed for a very light-skinned Black woman. According to Washington, Lois “marked out everything on her birth certificate and wrote ‘Negro.’ ”

Washington’s father Ralph was born in 1930 –– his sister Wanda was born around 1928. At the time, Lois lived in Chicago with the two kids and her itinerant, allegedly abusive longshoreman husband, who travelled for work for months at a time. Around 1942, Lois made a decision to drop Ralph and Wanda with a family named the Butlers in Coffeyville, Kansas. Coffeyville was home to remnants of one of the Osage tribes, but nobody knows if the Butlers were relatives. That part of the family’s history remains shadowy.

“She didn’t talk about that much,” Washington said. “Think about what women had to go through back then and even now. She had so few resources. Her best bet was to leave the kids and join the WAC.”

Lois enlisted circa 1943 out of Chicago. She was sent on a train to bootcamp in Georgia, and after graduation, she was placed in the 6888th Postal Battalion — “we think that was the only place that accepted Black women,” Washington said.

All this tracks with the storyline of Perry’s movie. The 850-member regiment received basic combat and gas mask training at Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia.

Per historical records, the women were transported to Birmingham, England, via Glasgow, Scotland, in 1945. The segregation from Georgia and the American South followed them to Europe –– the American Red Cross allegedly refused hotel rooms to the Black WAC and tried to house these soldiers separately. Then-Major Charity Adams, the first Black woman officer in the WAC, a preacher’s kid, and a well-educated woman, led the 6888th in a boycott of the separate accommodations, and her troops stood behind her –– this is not included in Perry’s movie, although there’s plenty of other historical info there.

After clearing the warehouses in Birmingham, the 6888th transferred to Rouen, France, to sort additional mail and cleared a three-year pile of correspondence in five months. In France, the 6888th were hailed as heroes and took part in parades. By the end of the war in 1946, the unit returned to Fort Dix, New Jersey, where they were disbanded.

*****

Photo courtesy of Moni Washington

And there the story would have ended, except for Perry’s movie and an awards ceremony 80 years later. In 2022, President Joe Biden awarded the 6888th Postal Battalion the Congressional Medal of Honor.

“You know, I found this stuff out four years after she died,” Washington said. “She never volunteered any of it. She came to everything –– when I enlisted, when I was commissioned, and she came to my duty stations, and she never said anything to me.”

Because Lois served two tours of duty in a combat theater, she would be classified as a combat veteran in today’s parlance. Modern-day honorably discharged combat veterans receive honor, recognition, and, more importantly, health care. As it was, the WAC received little appreciation and no medical care after their service as they weren’t formally recognized as Army.

Upon her return stateside in 1946, Lois went to Kansas to retrieve the kids from the Butlers and returned to Chicago. Possibly because of her experience in WAC, she qualified to work at the post office. She eventually remarried.

There’s also a question about Lois’ name: Was it Lois or Delores? “Her death certificate says ‘Lois,’ ” Washington said. “Everyone called her Lois.” It’s possible that when she left her husband and her kids, in addition to changing her race, she changed her name. In The Six Triple Eight, a light-skinned woman who identifies herself as Delores Washington declines to leave the Black women with whom she’d been chatting when the train they’re on crosses into the segregated South and the white women are moved to a different train car. It’s likely that that character is based on Lois Washington.

Washington says that she learned much later that the myth of the Black WAC was that they sent them to the European theater to be concubines for the Black soldiers who could not possibly date the white European ladies.

“They were made to host those Black soldiers,” Washington said.

Perry’s movie shows this, although in his version, the WACs are hosting a dance.

Military sexual trauma is something that the Department of Defense and the Veteran’s Administration started talking about only in the 2010s. “It’s something we just tolerated,” Washington said.

Also, at the time Lois returned, Black soldiers were discouraged from wearing their uniforms on American soil. “I wonder what she thought,” Washington said. Lois was part of the “silent generation.”

Washington’s dad Ralph “never told me [Lois’] stories, only his,” she said. Ralph came back with serious post-traumatic memories from his service, what we now call PTSD. He was reluctant to talk about any of his experiences. Washington remembers a time when she was very young when she slammed a door –– not on purpose –– and the noise sent her dad under the furniture in the kitchen. She called her uncle, who told her to go to her room and lock the door until he could get there to calm her dad and convince him he wasn’t still in Vietnam.

After her commission as a second lieutenant out of West Point, Washington was stationed at Fort Lee, Virginia, and Fort Benning, Georgia, “where I jumped out of planes,” she said. Her uniform has a parachute badge on it. Her terminal rank was lieutenant colonel (LTC). She spent a total of 25 years in the Army, both active duty and in the reserves, then went on to nursing school, continuing in her parents’ footsteps.

There’s a scene in The Six Triple Eight when the women finally arrive in the north of England to find the building they were to be housed in is uninhabitable –– between the elements and the rodents, it probably should have been condemned. The first thing the women of the 6888th had to do was clean the place.

Major Charity Adams’ character, played by Kerry Washington, tells her soldiers, “Your mothers have done worse,” likely referring to the fact that her mother was the great-grandchild or great-great grandchild of an enslaved woman, as well as to the working conditions widely available for American Black women at the time.

“I am so proud of my grandmother,” Washington said. “It was amazing to see this part of her life.”

While she was watching The Six Triple Eight this year, she said, “I lost my voice from screaming and cheering for those ladies. I resonated with the challenges faced by Charity Adams as I recalled my own experiences. I am a legacy!”

Photo courtesy of Moni Washington

Photo by Laurie James

Read about Cisgender women joining the fight for transgender liberation in Stronger Together in Metro.