It all happened really fast.

Emma Williams learned that her oldest son, a 20-year-old Black man named Bragg, was accused of killing members of a white family he worked for. Bragg was taken into custody and placed in the Hill County Jail.

The year was 1919. There was no radio and no TV. Many folks didn’t even have phones. Emma and her husband, Giles, lived in the country well outside of Hillsboro. Giles was away working. Bragg was intellectually disabled, and Emma couldn’t get reliable information on his status, the charges, or his case. She had to do something.

Emma, a mother of 15, instructed some of her older kids to watch the younger children and walked to Hillsboro with her youngest, baby Chester, on her hip. The journey was miles and took hours. And when Emma made it to the Hill County Jail, she learned that Bragg had been transferred to the Dallas County Jail until his trial.

No one had bothered to tell Emma, and her son Bragg didn’t even have legal representation yet.

Bragg was burned at the stake on January 20, 1919.

*****

Emma’s oldest granddaughter, Fort Worth resident Letha Young, 84, didn’t learn about the lynching until she was in her early 20s, and the information she received was sparse.

“At the time it happened,” Letha said, “my grandmother didn’t have anybody to really explain to her what occurred. She just got bits and pieces of the story. She never got a chance to speak with Bragg. It was impossible for her to go to Dallas with all the other children she had to take care of, so she never really talked about it. My aunties say my grandmother lived to be 100, but she didn’t really know what happened to Bragg, just that he was lynched.”

To 59-year-old Fort Worth resident Tonya Camel, Letha’s daughter, the story was heartbreaking. “I thought, ‘How could people be this mean and this cruel?’ It was just a whole new level of hatred and injustice. My great-grandmother always had such a loving spirit, loved her family, cracked jokes, made us smile … she was just the sweetest person. But when you think about what she had to endure, how she maintained such a brave face in spite of it all, I can’t image the pain she carried all those years.”

Bragg was the only suspect in the murder of a white woman and her white 5-year-old. In the early afternoon of December 2, 1918, Annie Wells and son Curtis were murdered at their home near Itasca (11 miles north of Hillsboro). The husband and father, George Wells, had gone to Hillsboro, and the older Wells children were in school not far away. Annie and Curtis’ attacker killed them, then carried their bodies into the Wells residence, setting it aflame to presumably destroy any evidence.

Neighbors and the older Wells children, who were on their way home from school, saw smoke in the direction of the home and retrieved the mother and son’s remains.

Described by the Waco News-Tribune as “tall and ungainly, and seemingly of low mentality,” Bragg was taken into custody. Before an official accusation was even made, a group of Hill County citizens attempted to lynch him, and the Hill County sheriff quickly transferred him to the McLennan County Jail, where a “Deputy Sheriff and Notary Public” procured an official confession that Bragg apparently signed an “X” to.

As lynch fever was in the air, Texas Gov. William P. Hobby received an urgent communication from an unidentified official in Hillsboro requesting Texas Rangers to protect Bragg. The January 13, 1919, message said that “the prisoner was in imminent danger of being lynched” and that the Hill County sheriff had stated that not only would he not stop white citizens from lynching Bragg but that he opposed any attempt by the Texas Rangers to protect the suspect. Gov. Hobby sent the Rangers, who transferred Bragg from Waco to Dallas, where he remained until his trial date. District Court Judge H.B. Porter appointed two well-respected Hill County lawyers, Walter Collins and Albion M. Frazier, to serve as Bragg’s defense attorneys. Collins and Frazier did so under expressed protest.

On January 16, 1919, Bragg was escorted back to Hillsboro by the Texas Rangers, and his trial began. Considering the nature of the charges and the atmosphere of the community, Collins and Frazier requested a change of venue for the case, but their request was denied. Then, proving Collins and Frazier’s point, it took days to seat a jury. The weather that January was bad (and coming to town was tough), but the citizenry’s predisposition was worse. When one Abbott citizen was questioned about his position on the case, his answer was succinct. “I’d hang him,” he said, his remark eliciting a round of laughter throughout the courtroom. Judge Porter cautioned the citizens in attendance, but the effect was negligible. An all-white male jury was eventually seated, but Bragg sat in the courtroom under the constant guard of six Texas Rangers.

Collins and Frazier entered a plea of “not guilty” for Bragg by reason of insanity. In terms of this plea, Collins and Frazier specifically noted that “malice aforethought” could not be demonstrated above the threshold of reasonable doubt. They suggested that Bragg’s intellectual capacity made him incapable of murdering someone with a “sedate, deliberate mind” and “pre-formed design” and pointed out that — considering the defendant’s intellectual disability — if Bragg had, as accused, slain Mrs. Wells, it could have been due only to a perceived threat as interpreted from his limited, cognitive perspective. This technically qualified the acts Bragg was accused of as self-defense. In fact, an identical narrative was conveyed in a mid-January edition of the Hillsboro Mirror:

Along the latter part of November, the Wells family was preparing to use their automobile, and a negro [Bragg Williams] working for them was starting the car, when he [accused] Mr. Well’s [sic] little boy with stopping the engine and the boy kicked him. The negro kicked him back and was discharged. On the second of December, while Mr. Wells was in Hillsboro the negro returned to the Wels [sic] home, and, according to the negro’s story, Mrs. Wells asked him what he wanted and he told her work. She asked him why he kicked her son and began abusing him and struck him in the head with a broom she held in her hand. He grabbed the broom and she reached for a gun standing on the gallery. The negro beat her over the head, knocking her down and then hit her over the head twice more. Mrs. Wells [sic] little four-year-old son then started for the school house which was only a few hundred yards away, and the negro started after him … hitting him over the head with the gun.

The Hillsboro Mirror’s account basically states that Mrs. Wells attacked Bragg with a broom, which, in a cognitively impaired person’s mind, may have constituted an imminent threat or have compelled a defensive response.

County Attorney Earl E. Carter and Assistant County Attorney H.P. Shead, however, were well aware of Bragg’s “low mentality” and prepared a professional refutation in advance to address the defense team’s plea. They brought in a Fort Worth alienist (the term for a psychiatrist or psychologist in those days) named W.L. Allison, and he undermined the defense team’s insanity plea.

Williams never testified in court, but a considerable cross-section of the community was aware of his reported confession. The prosecution subsequently produced two white witnesses who said they saw a Black man heading in the direction of the Wells residence before the murder and a young Black girl, Smithy McDuffy, who testified that she saw a Black man running from the direction of the residence after she heard the screams of Annie Wells. In the end, the verdict was a foregone conclusion.

On Friday, Jan. 17, Bragg was convicted of murder, and the Texas Rangers were abruptly and surprisingly instructed to depart. Bragg — arguably because he did not fully grasp the implication or gravity of the court’s verdict or sentence — laughed. The defense team’s argument that Bragg was intellectually disabled was perhaps nowhere better illustrated than with his awkward laugh. The white-owned, white-run, and white-staffed newspapers at the time would have pounced on Bragg’s laugh if it had been in any way malicious, ill-intended, or otherwise contemptuous or defiant, but no such reporting exists.

On the morning of Monday, Jan. 20, the court reconvened for sentencing, and Judge Porter condemned Bragg to be hanged on Feb. 21.

What happened next was unexpected.

Collins and Frazier had defended Bragg under protest, and his guilty verdict was popular. But once it was handed down and the death sentence imposed, the two attorneys deemed it unjust due to the defendant’s limited intellectual capacity and promptly requested a retrial. And when their petition for a new trial was denied, they immediately filed a notice of appeal to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

At approximately 11:45 a.m., a mob — upset by the appeal request and no longer in the mood for due process — assembled at the Hill County Jail and demanded Bragg be handed over. The jailers refused to give him up, so the mob battered the jail door down with a telephone pole, stormed the jail, and seized Bragg from his cell. The mob then dragged him to a concrete “safety first” post at the intersection of Elm and Covington streets on the southwest corner of the courthouse square and bound him securely.

A number of vigilantes quickly collected hay, wood, and coal and piled them around Bragg, dousing the combustibles in coal oil. A match was then applied, and the conflagration killed Bragg in a matter of minutes. Though he put up no resistance, he cried for help three times before the flames consumed him. Bragg’s body was left in the embers of the fire for hours. Photographs were taken of the atrocity (and one Hill County lawyer is said to have kept one of the images framed in his office for decades).

On January 21, Gov. Hobby denounced the lynching and initiated steps to investigate it. The next day, he sent a message to the Texas Legislature requesting a law that would put an end to mob violence and correct the assumption that members of white lynch mobs are not prosecutable. Hobby’s request was echoed by the NAACP, which sent a telegram to Hillsboro officials demanding punitive measures against participants in lynch mob.

On the same day, the San Antonio Express published a condemnation of the Hill County court’s decision to dismiss the Texas Rangers after the conviction. “If ever there was a fatal error of official judgment — whoever was responsible therefore — it was in this case. If ever there was a warning of lynching attempts, it was in this case.”

On January 23, Hobby instructed the Texas attorney general’s office to initiate an investigation into Bragg’s lynching. A Hill County grand jury subsequently examined charges against members of the lynch mob but adjourned without returning bills of indictment. Consequently, the attorney general’s office filed a motion to cite 12 members of the lynch mob (Jud Rufus Beavers, Will Browning, Joe Ferguson, Cole Hammer, Earl Hobbs, Jim Hobbs, William Pinckney Hightower, E.L. Stroud, George Wells, William R. Wells, Poly Wilson, and Wiley Wilson) for contempt of court in regard to the Court of Criminal Appeals motion, because the vigilantes had lynched Bragg after his appeal had been filed and was technically pending.

It was a well-conceived attempt to prosecute members of the lynch mob in a higher court, especially as it was obvious that they would not face prosecution in Hill County. The motion was described as the first of its kind in Texas, but it, too, fell short. No action was taken on the motion in March or April, and the attempt quickly faded into obscurity.

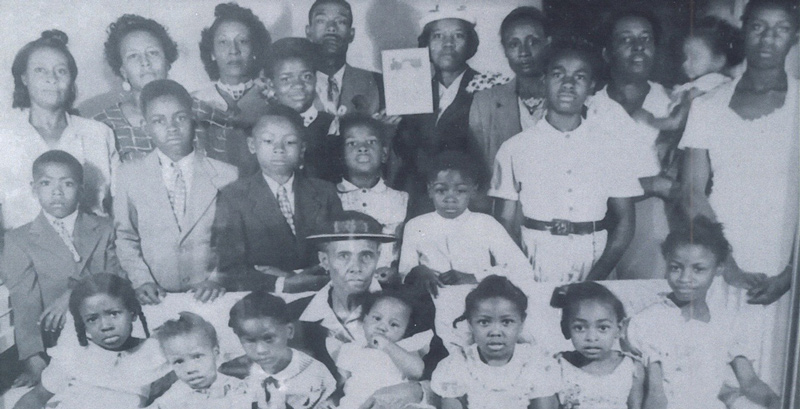

Courtesy of the Williams family

*****

As I’d written about Bragg Williams’ lynching in the past, I began working with Bragg’s family to pursue a historical marker acknowledging his horrific fate. Letha Young perhaps expressed the family’s thoughts best at the time. “We don’t know what happened or whether Bragg was guilty or not. The whole thing makes me think of Hang ’Em High with Clint Eastwood. He gets hung by some vigilantes for something he didn’t do, but the sheriff comes along and cuts the hanging rope loose before Eastwood’s character dies. Where was the sheriff or the police when Bragg was being burned alive on the courthouse square?”

“We needed to do something,” added her daughter, Tonya, “because justice was never done and Uncle Bragg never received due process — and nobody had to answer for it.”

On March 8, 2022, several of us — Letha, Tonya, Letha’s then-68-year-old sister Crady Johnson (also a Fort Worth resident), and I — approached the Hill County Commissioners Court regarding our intentions, and though not enthusiastic, they didn’t seem hostile to our effort. County Judge Justin Lewis came over and talked to Letha, Crady, Tonya, and me and admitted that a cruel injustice was committed in Hill County after Bragg’s trial and that he didn’t think we would have any problems procuring a marker. We were skeptical, but Lewis seemed forthright and honest, and we were cautiously optimistic.

On April 5, we submitted the marker application (with Crady listed as the primary sponsor), and on April 18, the Hill County Marker Chair, Jana Burch, informed us that the marker narrative was: 1.) missing a context section, 2.) that there was no evidence that Williams was intellectually disabled, and that 3.) the application needed to be better documented. It frustrated us, but we dug deeper, went to some lengths to substantiate claims of Williams’ cognitive impairment, and addressed the documentation issues. The marker application increased from 10 to 21 pages, and we resubmitted it.

*****

Things happened really fast, again — and again without Bragg’s family’s knowledge.

Months passed, and we heard no word. On November 2, 2022, I sent an email to the Texas Historical Commission attempting to confirm that our marker application had been passed along and that everything was in order. I received a disturbing email in response to my query two days later:

The application for the Bragg Williams Lynching was received, however the application was canceled on October 10, 2022 due to the marker fee not being paid. We encourage you to re-apply next spring when our application period opens from March 1-May 15.

I was distraught. The marker application had been approved, and no one let us know (or made sure we knew).

I immediately phoned Crady and asked her if she’d received news of the application and she informed me she had not. I told her to check her email and contacted the Texas Historical Commission. They confirmed the email had been sent, and I told them we’d received no word and that the marker sponsor may have missed the email.

Crady called me back, letting me know that she had unwittingly received the email but missed it because she only checked her emails on her phone. She forwarded the notice to me:

Congratulations! The THC Commissioners have reviewed your application and staff will now be proceeding to the inscription. The marker fee is now due, payable and received in our office by 5pm CDT on Friday, September 16, 2022 — THC Marker Staff

Crady and I were shocked and wildly dismayed.

The Texas Historical Commission representative was sympathetic but didn’t know what could be done.

Crady and I were both frustrated beyond words. The marker application process had been tedious and frustrating, and we didn’t want to have to refile. The announcement of the marker application’s approval — which should have been a joyous occasion — was now a nightmare.

At this point, I sent a barrage of emails to the Texas Historical Commission and the Hill County Historical Commission. I wondered if it didn’t fall under the Hill County Historical Commission’s purview to make sure marker applicants were informed of the marker application decisions and particularly if they had been approved. The Hill County Historical Commission chair and the Hill County marker chair both informed us that they never received the email communicating the Bragg Williams Lynching marker application approval.

On November 7, we reached out to the THC expressing our concerns and imploring them to allow us to pay the marker fee and bring the arduous undertaking to fruition.

Thankfully, on Monday, Nov. 14, 2022, the Texas Historical Commission re-sent the marker payment request, and remuneration was made immediately. A receipt of the payment’s processing was conveyed to us by email on November 15.

*****

The Bragg Williams Lynching historical marker was delivered to Hill County on October 23, 2024, and it will be placed on the southwest corner of the courthouse lawn in Hillsboro. The marker is set to be dedicated on MLK Day, January 20, 2025. The dedication ceremony will start at 12:30 p.m. and end at 1:30 p.m. On that day and during that time, Bragg’s family and others will commemorate the atrocity he was a victim of and celebrate the strength and courage of his mother, Emma Williams. Though she never got to see justice done, she was the glue that held the entire family together.

“After Bragg was lynched,” Crady said, “my grandmother picked up and moved. She was determined to get her family to safety. Sometimes the trees we plant … we never get to enjoy their shade, but I think she would be very pleased by this historical marker.”

Letha agreed. “I feel like my grandmother has gotten some of the justice she never got when it happened, that someone has finally recognized that she and Bragg were human beings. I don’t know the full story, but my grandmother was never told the whole story. It was bad, and she lost her oldest son. She did the best she could with what she knew.”

When I asked Letha how she felt about other Texans not wanting this type of history discussed or recorded in history books, she was frank. “I’m quite sure there’s a lot of people that feel this type of history should stay buried, but it seems to me that this is God’s way of making some right of this wrong.”

Crady concurred. “This year, MLK Day falls on the same day as the 106th anniversary of my grand-uncle Bragg’s lynching. I think it’s fate. Fate has a way of bringing things together. Dr. King’s message was one of peace and the will to bring us all together. Who would have thought? It had to have been part of God’s plan.”

Photo by E.R. Bills

*****

Was Bragg Williams guilty or innocent?

Was Bragg not guilty by reason of insanity? His well-respected and undoubtedly qualified local attorneys believed so, but Collins and Frazier were ignored and Bragg was denied due process, so we’ll probably never know. A January 24, 1919, editorial in the Vernon Record, however, sounds eerily contemporary:

The law’s delay is responsible for most of this. New trials, secured as a result of a maize [sic] of technicalities which the legal fraternity has woven, appeals and reversals without regard to the guilt or innocence of the prisoner or whether an error committed had anything to do with the meeting [sic] out of justice — these things have given birth to a disrespect for law — and impatience of even necessary delays — that, unchecked, threaten imminently the perpetuity of free institutions.

“Due process of law” has ridden roughshod [over] justice and decency.

It’s easy to forget or misremember today that the cruelties and injustices endured by the forebears of our Black friends and neighbors were uncountable and limitless. Ultimately, they are now unknowable, and, finally, they are no longer prosecutable. But does our well-being today really require they be ignored and forgotten?

While recently discussing this issue with a Black friend of mine, someone I hold dear, they shared something no one had ever said to me before. “Black people know what’s been done to them. You don’t have to tell us. We know.”

It stung me.

Especially as a white person. A white man.

I sensed it before, but no one had ever just come out and said it to me. And, in that moment, I knew it in no uncertain terms. Black people know. Black people know it bone deep. My friend was essentially expressing the concept of generational trauma without polish or platitude.

Which raises an unavoidable question.

If Black people know what’s been done to them, why are we so insistent upon ignoring what was done to them?

Don’t bristle.

Don’t recoil contemptuously.

Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech was delivered on August 28, 1963, to more than 250,000 civil rights supporters from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. — 62 years ago, in fact, and most of us, even if we don’t remember much else of what he said or what he stood for, do remember the name of that speech. We even admire him for it, even if we can’t recall the content or context. We simply remember that he had a better vision for America, a vision where people from all races and creeds and walks of life lived together in greater harmony.

So, let’s be honest.

Are we anywhere close to Dr. King’s dream or vision?

Letha’s view on the subject is astute. “I think Dr. King was way ahead of his time. His speeches still address what’s going on in the world today.”

Crady’s opinion is one of obvious concern. “We have made some progress, but I think Dr. King would be disillusioned with us as a nation. Younger people are not being taught what he was trying to tell us. We can’t change the past, but we can change the future. His message is being lost across the board on both sides.”

During his campaign, President-elect Donald Trump promised to kill federal spending on diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, reversing former President Joe Biden’s practices and vowing also to eliminate DEI government employees and “direct the Department of Justice to pursue federal civil rights cases against schools that continue to engage in racial discrimination.” Trump also proclaimed that universities would be held accountable for their persistence “in explicit unlawful discrimination under the guise of equity.” Vice President-elect JD Vance was one of the sponsors of the Dismantle DEI Act in the Senate last summer, which mandates the elimination of all DEI programs and funding for “federal agencies, contractors that receive federal funding, organizations that receive federal grants, and educational accreditation agencies.”

Our own governor, Greg Abbott, tap-danced and stomped on programs that might have promoted Dr. King’s dream three and a half years ago, when he signed House Bill 3079 into law. HR 3079 bans honest conversations about race, censors how teachers teach current events, and bans students from receiving credit for participating in civic and/or civil rights activities.

Does anybody really think this is what MLK’s dream was about?

There’s no reason to mince words.

Too many white male politicians know Black people know what was done to them. They just don’t want their own kids or grandkids to know about it. They don’t care that Black men like Bragg Williams didn’t receive due process, and they don’t care about the pain Emma Williams carried until her death.

But why should it matter to them?

Americans from every color and creed and walk of life continue to elect or reelect politicians who prohibit a full embrace of Dr. King’s dream. Americans don’t even believe in America anymore. Why should their political representatives?

*****

Some members of the Williams family have expressed concerns about attending the dedication ceremony, especially in the age of MAGA hatemongering, but Tonya’s faith is inviolate. “If God brought us through this and made the marker happen for Bragg and my great-grandmother, he’s gonna take us the rest of the way. They want us to be in fear, but the purpose of this marker is not to stir up any ill will. My grand-uncle has been dead for over 100 years. What’s done is done, but acknowledging the injustice that he was a victim of matters.”

And when I ask members of the Williams family about any advice they might have for citizens like them in towns and cities where other Black men were burned at the stake — Belton, Temple, Waxahachie, Tyler, Sherman, Paris, Rockwall, Greenville, Sulphur Springs, Kountze, and others — they are unequivocal.

“People do better when they know better,” Letha said.

“It may be a real fight,” Crady warned, “so anticipate setbacks. We were blessed. The Hill County Commissioners were on board. It won’t be the same everywhere.”

Tonya advised, “Have faith and press forward.”

Contrary to what too many white Americans and white Texans believe, historical acknowledgment of the atrocities Black Americans have suffered for most of their existence in this country is not about guilt-tripping whites or Black bragging rights. It is simply about human rights.

Bragg’s rights.

Fort Worth native E.R. Bills is the author of The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas and Tell-Tale Texas: Investigations in Infamous History.