This happened the other day. Tham, the adventuring party’s blue-skinned, ram’s-horned tiefling rogue, succeeded, against all odds, in two consecutive, improbable feats. Despite his slender build and lack of physical strength, Tham managed to pick up his companion — a halfling rogue named Lord Claxton, nimble and stealthy but about the size and shape of a beer keg — and heave him in the direction of his other companion, a diminutive gnome wizard named Wendell, who was currently plunging from 30 feet above toward the tangle of spiderwebs that spanned the width of the cavern, woven beneath the crumbling stone bridge they’d been crossing.

Moments before, a rubbery, rope-like appendage snaked down from the shadows of the cavern’s ceiling, grabbed Wendell around the waist, and reeled him toward the latest monster trying to eat him. What had previously looked like a large stalactite now bristled with six 50-foot tendrils. It had already caught Garrekh (of a species of underground-dwelling dwarves called duergar, whom Tham, Wendell, Claxton, and their vainglorious warlock comrade Barry “Handsome” Daytona were escorting to the Undermountain town of Skullport), taking a bite out of Garrekh but dropping him when he fought back. Garrekh had been saved from his fall when he was caught in the arms of a frog-like monster known as a “slaad,” conjured and controlled by Barry. But Wendell was beyond the slaad’s reach. The stalactite creature’s tendrils whipped about frantically, and it drew Wendell nearer to stare at him with its single, bulbous, crimson eye. The eye’s pupil narrowed, and the thing drew Wendell toward the gnashing, slathering maw below its eye, a horrible gaping frown full of fleshy, bulging gums and yellow, jagged teeth as big as broadswords.

Photo by Steve Steward.

Wendell uttered an incantation and flailed his hands at the thing’s huge eye, and a pulse of necromantic energy coursed forth from his palms. The thing’s stony skin nictated over its eye, and it roared in rage. But other than making the monster mad, the spell had no effect. Wendell, formerly a cleric, uttered a prayer to Ogma and squeezed his eyes shut, awaiting his fate.

Claxton, who’d just extricated himself from a glob of webbing blasted on him by a mastiff-sized spider, saw Wendell get yanked up from the bridge, ran within throwing range, and expertly chucked a dagger at the tendril clutching Wendell. The stalactite monster brayed a hideous scream and snatched its tendril back, and Wendell tumbled into empty space. Claxton heard Tham call his name, saw Tham nod at him, and was clueless until he saw that Tham held the end of a rope, the same rope he’d tied around Claxton’s waist in the dungeon chamber that contained a gigantic, room-sized ooze.

“Shit,” Claxton said. Tham grabbed him, spun him, and threw him, grabbed the end of the rope, and dug in his heels as the rope fed out. Claxton sailed up toward Wendell and caught him midair, amazed that it all worked out, so amazed that he hardly noticed when he and Wendell swung around the bottom of the bridge and back over the other side. Garrekh, who had used his innate duergar magic to double his size, casually turned and caught them as they roped through the air, and the stalactite creature scuttled away from them across the ceiling.

*****

Photo by Steve Steward.

If you can imagine the X-Men’s Nightcrawler with horns curving back from his forehead, a couple of gold teeth, and an unhealthy paranoia about shapechangers, this is who Tham is. He’s the creation of my friend Kolin Jardine, who, along with Sam Anderson (Lord Claxton), Jordan Dyer (Wendell Longnose), and Christian Carvajal (Barry “Handsome” Daytona), has been playing in a weekly Dungeons & Dragons campaign with me that’s been going on for over two years. They are the Player Characters, whereas my role is the Dungeon Master, or “DM,” who portrays the monsters and other characters with whom the players interact. I am also a referee, who decides, per the game’s official rules, what the characters get away with. Other players have moved in and out of the group — shoutout to Shannon Wiley and her aquatic bard Kleio, as well as Ross Van Gorder and his half-orc barbarian Roscoe Fockshite — and this week, Garrekh, normally a non-playable character (NPC) the other guys have to keep from getting killed, was played by Jordan Richardson, who had played only one other time and wanted an uncomplicated character to learn the rules with.

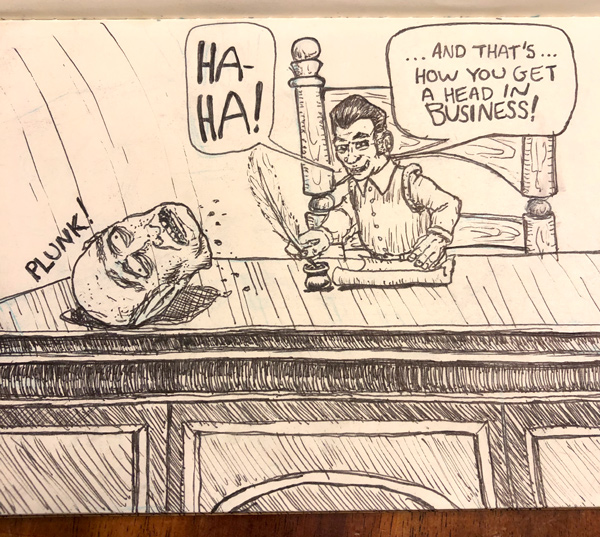

When not engaged in the game, we are just grown-ass people with jobs and such, fortunate enough that we are all off on the same day during the week to sit around, eat snacks, drink beer, and pretend to cast spells and throw daggers. I don’t want to speak for the other people in our group, but Monday afternoon is pretty much my favorite part of the week. For three to five hours, we get to escape whatever hassles or stressors are crowding our respective mental spaces, filling them instead with the details of a long-running, slaphappy adventure story in which a hero might use a conjured spectral hand to pants a city guard, and powersliding a horse-drawn wagon through an oil fire is possible. Our game’s vibe is like if Adam Sandler or Judd Apatow were the showrunners of Game of Thrones, or if Willow were R-rated and written by Chuck Jones.

Photo by Steve Steward.

D&D is a collaborative effort in storytelling. The DM — me, in this case — narrates the setting, describes encounters, and referees the players’ reactions to and interactions with the world. There’s a jazz-like rhythm in a gaming group that, once uncovered, makes game sessions as memorable as playing a concert to a room full of friends. Like playing an instrument, there are rules and conventions and mechanics (all of which are built atop an underlying foundation of math that you either understand or get by without) and mistakes and flubs that can be just as entertaining as a perfect performance. As a group, you celebrate the triumphs and bemoan the defeats, lauding the fallen while elevating those who survive to level up their skills. It’s an emotional ride, as silly as it sounds, and that’s also a thing that I love about it. The excitement and delight in succeeding is practically electric, as evidenced in Tham’s heroic move.

What made Tham’s Amazing Claxton Toss improbable relates to the basic mechanic of D&D, which involves rolling a 20-sided die, known in game parlance as a d20, and comparing the result to an arbitrary “difficulty class” number — an easy task is a 5, a challenging task is 15, and something that is nigh impossible is a 30. Each character has various “modifiers,” which are bonus numbers that can increase the likelihood of success. As an example, let’s say Sam wanted Claxton to pick a lock on a treasure chest. The lock, per DM fiat, has a difficulty class (abbreviated as “DC”) of 17 (maybe because it’s made by some ancient elves known for making unpickable locks). When it comes to lock picking and other “sleight of hand” activities, Claxton has a modifier of +5, which he adds to the number Sam rolls on the d20.

Sam rolls a 13, which with the addition of the +5 makes 18, which is enough to beat the DC. Claxton picks the lock, opens the chest, and gets sprayed with a magic poison that makes him age into an 80-year-old, and then he spends the next few sessions acting like Jerry Stiller on King of Queens until he finds a way to fix it.

Photo by Steve Steward.

In the case of Tham’s Improbable Claxton Toss, Kolin articulated what his idea to save Wendell was, and I made a ruling: Because Claxton is stout, and Tham isn’t strong, but Kolin’s idea was funny, I decided there would be two DCs to beat: a DC 13 Strength check to grab Claxton and throw him and a DC 18 Dexterity check to “lead the pass” at catching Wendell. Kolin rolled a 14 on his Strength check. Then came his roll for Dexterity. Kolin jostled the die in his palm, hyped himself up like he was at a roulette table, and dropped it into the top of his dice-rolling tower. It clattered to a stop at the bottom. Kolin looked down, paused, and announced, “Nat 20.”

The table erupted in cheers, because a roll of 20 on the d20 (known as a “natural” or “nat 20”) guarantees automatic success on whatever your character is attempting to do. We ended the session with the characters escaping death and exiting the cavern to whatever fate I come up for them next time.

*****

Sounds fun, right? Unfortunately, all that fun comes with a bit of patience, because D&D is full of rules that the participants all have to be mostly familiar with. To the uninitiated, all those numbers and the seven different polyhedral dice might seem impenetrably complex. And some of it is. I’ve been playing for four years now, and I still have to look up lots of rules. But in my experience, that’s what lends itself to the style of play in my group. I probably should’ve set the DC’s for Tham’s Claxton Toss at 14 and 20, because of how the rules of a characters’ attributes play out, but it was way more fun to invite his success at such a wacky attempt at heroics. For new players and the DMs trying to kill their characters, here’s some advice I’ve stolen: As long as you all agree and are consistent with how you apply them, then use the rules you like, and ignore the ones you don’t.

In fact, that advice is especially relevant now, because D&D’s parent company, Wizards of the Coast (itself owned by toy company Hasbro), just released an updated, revised edition of one of the game’s core rulebooks, the Fifth Edition Player’s Handbook. The 2024 version updates various rules and options from the most recent updated edition in 2014, known colloquially as “5e,” and if you go on YouTube, Reddit, X, or any other social media channel you can think of, you can learn about what all those updates are and whether they are cool or not.

Photo by Steve Steward.

I have watched very little of this content because I find the discussion about “old thing versus new thing” exhausting. For new players and DMs, though, a lot of these videos are useful. I was once one of those, and I have seen hours of that stuff. But the best way to learn the game is to play it, and if you can’t find a group, it’s still pretty fun to learn the rules and make a character, and in those two endeavors, I think the new Player’s Handbook is very useful. Primarily, I think it offers enough new ideas and a more streamlined, explicative process for character creation to make it worth the purchase, especially for new players. And if some of the 2024 updates have nerfed a character class or spell or whatever, so what? It’s your game. Un-nerf it to your heart’s content.

Personally, I prefer the physical books to their online counterparts, though D&D’s online presence, DnDBeyond.com, has everything you need to start playing, even without a subscription, and making a character on that site is way easier and faster than doing it the old-fashioned way using pencil and paper. Richardson, along with his wife Mallorie, my partner Hayley, and our friend Jana, recently built characters with me using the 2014 Player’s Handbook. The process ended up taking a couple hours because no one except Hayley had played before, and I got tripped up trying to figure out some of the math behind their various abilities. In hindsight, I would’ve had premade character sheets or had them log on to the website. We still had fun, and Hayley’s character almost died in the short combat encounter we had time for, laughing that her half-orc fighter nearly got felled by a single goblin arrow.

Commiserating over imaginary failures and successes is but one joy to be found in playing D&D. I began playing in an online game during the 2020 COVID lockdown, one of the many neophytes whose introduction to the game came via Zoom windows across various online table-top apps. In March 2021, CNBC said 2020 proved to be Dungeons & Dragons’ biggest year ever, with sales jumping 33%. D&D became mainstream that year, and, suddenly, that old joke about “Jesus saves, everyone else takes damage” made sense to more people than ever before.

Photo by Steve Steward.

Then came the Chris Pine-led Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves, which turned out to be a pretty good theatrical adaptation of the brand and spirit of the game. There is the Dallas-based promoter High Fantasy Events, which throws regular D&D-themed dance parties throughout Texas, where costumes are highly encouraged. In Denton on the Square sits the d20 Tavern, a growler and boardgame bar with regular D&D events, and The Cicada has recently started a D&D happy hour from 4pm to 7pm on Thursdays. Dungeons & Dragons is pretty much culture canon now.

Though I didn’t start playing until the wizened old age of 41, I was certainly aware of and captivated by the brand as far back as I can remember. First there was the Saturday morning cartoon, launched on CBS in 1983. I was 5, and my parents, newly born-again Christians, were not thrilled about it, so my memories of it are dim. When I got into comic books in the late ’80s, it was the D&D advertisements that filled my brain with wonder, none more than the Larry Elmore cover to the Basic Rules. The look of sadistic rage on that red dragon’s face, talons spread in a gesture of outrage as it loomed over a couple acres of glittering treasure somewhere deep within a ruined temple, is seared into my brain. That fighter in the foreground, for all his glowing sword and scale-mail armor, didn’t stand a chance, I just knew it.

More than anything in the dizzying blocks of text, it was the artwork in the D&D books that fired my imagination. There was this guy in my 10th grade AP European History class who first showed me the fabled Monster Manual. I understood none of the stats and rules, but I drank up the art like a wounded wizard in dire need of a health potion. That Larry Elmore Basic Rules cover, the cover of the Fiend Folio, emblazoned with what looks like a mummified vampire covered in jewels and armed with a huge golden sword — these and the other iconic D&D books from the ’80s and ’90s stared at me for years from the shelves of B. Dalton and Waldenbooks, Barnes & Noble, and the back part of every comic shop I ever set foot in.

Nowadays, the D&D stuff is usually near the front of the comic book shop or at least it is at Y2K Comics in Wedgwood, my usual source for D&D minis, the little plastic monsters and adventurers my group uses on a dry-erasable battlemap gridded in 1-inch squares. I’m sure my mini habit is not as pronounced as others, but — wow — have I acquired a lot of them. Does a D&D session need two dozen skeleton minis? You just never know.

Photo by Steve Steward.

*****

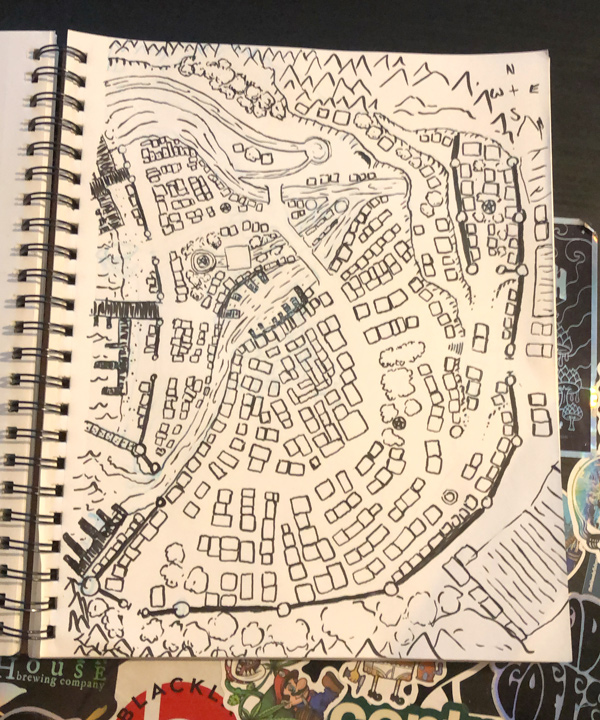

I never thought I’d be interested in the minis and maps that in-person, table-top games often feature, but here I am, crossing my eyes with a thin paintbrush in my hand, trying to paint the eyes on bugbear chieftain, who, after my treatment, ended up looking cross-eyed himself.

Going deep into the peripheral parts of D&D — painting minis, buying supplementary books and other material, getting a monthly dice subscription — all of that is fun, but most of it is kind of pricey. Luckily, none of those accouterments are necessary. I’d argue that D&D played within the “theater of the mind” is the best kind because it requires participants to focus their attention on one another. It’s a lot of active listening and spatial abstraction — imagining the distance between your character and the troll stomping over to claw him to death is more mental exercise than staring at a screen (or even a map full of minis) and tapping a “roll dice” icon. Empty beer cans, stacks of poker chips, and squiggles drawn on paper are just as representative of topography as the highly detailed 3D-printed map terrain sold in Etsy stores. All the online and offline pieces that make D&D arguably easier — the website and the virtual table-tops and their endless supply of digital tokens, maps, and other enhancements available for purchase — I am wary of these things because they make you look at a phone or a monitor instead of relying solely on your imagination. For me, the point of playing this game every week is so that I don’t have to glance at those things for a few hours. But I have also had a ton of fun running and playing in online games, even when my overloaded maps crashed or somebody’s internet connection was wonky. D&D is about telling a collaborative story, but more importantly, it’s about hanging out with your friends.

Photo by Steve Steward.

Above all, that’s what I love about this game. More than once have I seen some article in my feed about how difficult it is for adults to make new friends or do things with the ones they have. D&D is probably not a great “game night” kind of game, as character creation and rules-setting usually require a separate “zero session” that takes as long as a normal session might, which, if everyone is having a good time and the dice are hot, might last a few hours. But it’s worth getting together with people and at least trying to figure it out. If nothing else, you had some beers at your friend’s house while trying to play the dice game with the little plastic monster guys and the grid, like the kids on Stranger Things.

I don’t think it’s a game for everyone, either. The rules are clear and comprehensible, but the learning curve can seem a little steep — there’s a lot of jargon and a few abstract concepts that might take a while to wrap your head around. Some people might find it boring, which I also totally get. Even when you play regularly, like almost every week for months and months in the same campaign with the same characters, some sessions are less thrilling than others, and sometimes a session can be downright stale. A puzzle might be too abstract or the DM might be under-prepared or it’s hot in your buddy’s dining room where you’re playing and half the group is hungover. These things make D&D a little bit of a drag. Emotions can get a little frayed, too, like when a player gets frustrated with their DM’s rulings or when the DM gets frustrated with their players’ misunderstanding of the rules. In that regard, the saying that “no D&D is better than bad D&D” is one to live by. If you’re not feeling up to playing for a few hours — and with the state of the world as it is, pretending to be a wizard or whatever around other people can be a lot harder than you think — do your friends a favor and sit that session out.

But for all the potential for burnout, the camaraderie and memories you make from a fun D&D session are worth the occasional slog through another dimly lit passage, getting changed by the same pair of carrion crawlers again. Hanging out for a few hours with your friends is what D&D is for, no matter what you roll on the dice — after all, getting some adults together for a few hours is successfully completing an improbable task on its own, but when one of you rolls a nat 20, that’s something you end up talking about for a long time.

Photo by Steve Steward.