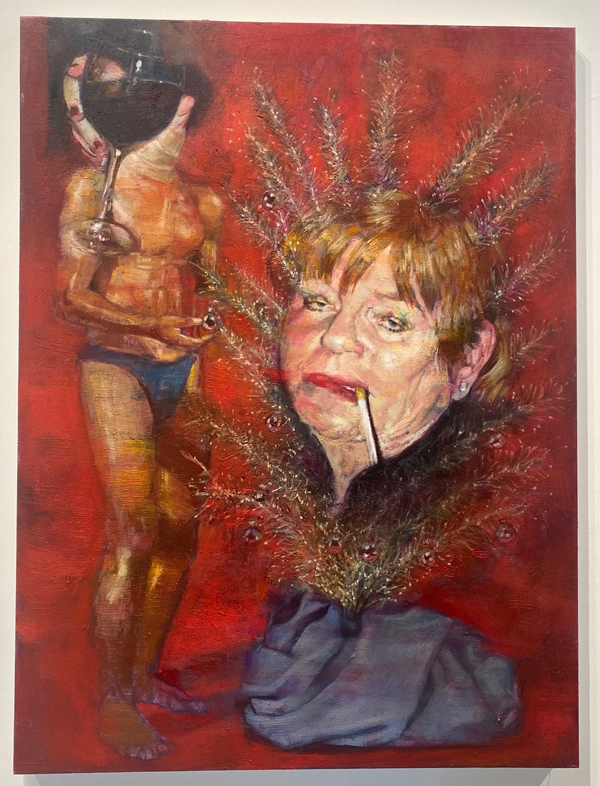

As soon as I saw her, I LOL’d. A cigarette dangling precariously from the side of her mouth, her tangled strawberry-blonde hair matted against her sagging white skin, her dark eyes drooping, she was not what you’d expect to see in a painting in an established gallery. Maybe the wine was to blame. The face of a slender bronze man wearing only blue briefs hid behind a full glass of red as the haggard woman’s visage obscured an anemic-looking tinsel tree. “Paulo & Paula” really spoke to me. What did it say? “Let’s party,” obviously, but also WTF?

Photo by Anthony Mariani

And I mean that in the nicest, most flattering way. A couple years ago, I interviewed the artist, Jay Wilkinson, for a story I was writing about his work or art in general or Fort Worth or something, and we started talking about photorealism today. Essentially, the Fort Worth painter said (and I’m paraphrasing here), his pieces demand a figment of the surreal to separate them from photography and just to keep his canvases engaging and viewers thinking. With paintings like “Paulo & Paula,” you see what Wilkinson’s brand of contemporary photorealism can achieve: prolonged dialogue. Are Paulo and Paula a couple? Is he with her just for her money? Is she with him just for his virility? The deep, rich red background gives the mise en scène a theatrical feel. Is the curtain going up or down on their bad romance?

Sparking the cultural conversation while simultaneously documenting it, a lot of the work I came across last Saturday around town as part of Fall Gallery Night seemed like a lively bar at happy hour. Lots of points of departure into big ideas. Lots of bugged eyes. Creased foreheads. Smiles. And some gratis beverages. *bows*

*****

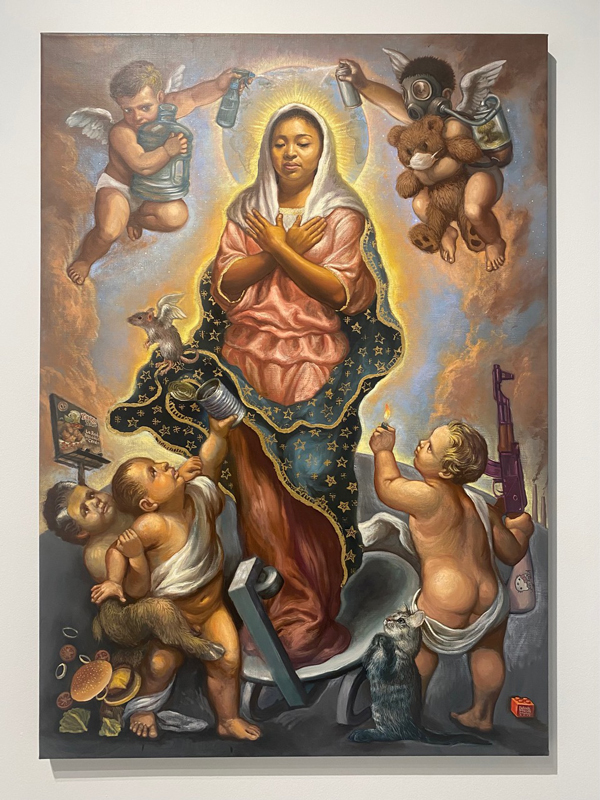

I must have stood and stared at “Mariamundi” for 10 minutes straight. In the Latin-forward group show at 400H Gallery in Sundance Square, Patrick McGrath Muñiz brings the Virgin Mary to the barrio. Cherubs pay homage. As two create the brown-skinned saint’s halo by spraying her with water and an aerosol can (spray paint? hairspray? Off?), three clamor for her attention from below, one extending a lit lighter toward her while clasping a rifle with Hello Kitty painted on the handle. The cryptic references jump all over the place. Following them leads nowhere. What matters is the vibe. “Mariamundi” is a vibey painting, and what it broadcasts is humor, satire, and irony. It also may also have you questioning the artist’s motives. Is the Latina Mary Muñiz’s wife? His mother? A complete stranger? What does he think of her? Probably not anything too great, but it’s not all bad, either. Just like family.

Photo by Anthony Mariani

Self-mythology works just as well as any pastoral landscape or tables of fruit for inspiration. You can tell that Jesus Treviño plucked the leisurely characters in his “Beyond the Border Chisme,” also at 400H, from real life — the crude black-and-white sketches on paper suggest he penciled them one afternoon en plein air or from a nonchalant pic. The beauty comes from their framing. They sit behind black, faux-wrought-iron fencing like the kind found on houses and storefronts in poor communities. Instantly, even non-Latinos can connect to this common Latino decorative element. The prolonged dialogue that results isolates our feelings about barrio life. At once dangerously foreign and as close as our family, friends, and neighbors, this is art at its simplest yet most powerful peak.

I don’t know about the art world at large. I only skim Artforum and haven’t left Fort Worth to visit another big city in years. What I can say with some confidence is that Fall Gallery Night proves the lockdown and post-pandemic explosion in sequestering and scrolling seem to have brought artists’ personal lives to the fore. This is not necessarily a bad thing. We crave prolonged dialogue especially if initiated by talented artists with something new to say or a novel way to depict handy references or rhetorical/philosophical cliches (corporations = bad, environment = good, herd mentality = bad, diversity = good, for example).

Longtime favorite Clay Stinnett serves up two huge, mesmerically colorful canvases straight from the groovy 1970s. Hanging at Fort Works Art, his massive pieces consist of dozens of small, mostly square, sometimes text-heavy vignettes, each its own mini-painting. Euro Jesus above the words “Forgiveness Stops,” Spider-Man, “Doom Scrolling,” E.T., a “Cobra Chopper” motorcycle, a skull, zombies, Satan, everything rendered in the local painter’s signature nervous style — I’m not going to ascribe any deep meaning to them. Let me just say that as a collector of vintage Uncanny X-Men and The Incredible Hulk, Stinnett’s tableaux hark directly to the pages of ’70s-/’80s-era comic books. Even non-nerds can feel older generations’ curdled sentiment in his patently cheesy imagery. Just try not to smile.

Nearby, Kristen Moore’s locally famous “Waffle House (Late Night)” (which sold for $10,000) also goes down smooth like a cup of black java placed lovingly on some Formica. The painting is so popular because it amplifies the power in perfect, hypernatural color combinations and nonserious or nonacademic subject matter. Plus, that sunset is delicious.

Erika Duque Scully’s tasteful floral paintings in the room next door provided a contrapuntal tonic, which was welcome. And it’s nice knowing that a progressive venue like Fort Works Art recognizes and supports serious, academic art.

Photo by Anthony Mariani

*****

The Westside spot was the second stop on our Fall Gallery Night shenanigans. My wife and I left long before future-pop gal-and-guy duo Yokyo performed on the rooftop and the market in the alleyway behind the Westside gallery opened. I hated missing it. Not only should more bands be performing on rooftops above adoring masses and art markets, but what a wonderful way to bring non-artists into the fold. We need more of this. Every month. If not at Fort Works Art, then somewhere equally funky.

Our first stop of the day was William Campbell Gallery’s Arlington Heights location. Restrained, quiet, Scully-esque art for us as opposed to art for the artist, John Fraser’s Fragmented Serenity sneakily blended into the walls. The late Illinois native’s palette of beiges and browns with nothing much going on between them reminded me of a hanging deconstructed cardboard six-pack case I fell in love with decades ago at some art space in New York City. The craft matters. The organization matters. The details matter. Every line of Fragmented Serenity is precisely rough, every muted square, rectangle, or found object sublime, every right angle exaggeratedly measured. Taking it all in, you knew you were in the hands of a master. The exhibit could not have been more different from all the muscular, referential, colorful work hanging at all the other galleries we visited. Again, I had to applaud Fort Worth’s diversity of thought and approach.

In any scene, there’s always art for us and art for the artist. Art for us is approachable, collectible, good for hanging over the fireplace, often nonrepresentational (unless we’re talking landscapes or still lifes), and often pricey. Art for the artist is hermetic, which doesn’t mean it can’t be fantastic (see: Muñiz, Stinnett, Wilkinson, et al.). As social media proves every second of every day, we love peeking into others’ lives, and when these others have engaging things to say and an artful way to say them, looking away impoverishes our eyeballs. I’d even argue that a canvas can reveal 10 times more about the human condition than some literalness-loving screen. A truism: Art for us and art for the artist embolden each other. There’s room for everything. And everyone. (Except a lot of women, apparently. Picking mostly at random, most of what my wife and I saw was male-heavy.)

Photo by Anthony Mariani

*****

There were two other interesting shows we came across. Both by names. Both representational. Both pretty serious. Adam Fung drew inspiration from his 2023 artist residency in the Arctic Circle for his solo show at J. Peeler Howell Fine Art. Is there cell reception up there? Could any of us normies go even two hours without any bars? Two minutes? Did the TCU art prof care either way? All we know for sure is that he spent a lot of time documenting his environment. Comprising nearly two dozen oil/wax paintings on linen, mystic sea revolves around the ocean.

“In suggesting an oracle-like quality to the landscape,” Fung says in his artist’s statement, “I want to pause and ask: Do we look for, listen [to], or heed what the natural world foretells? Shifting to the sea as a site — that is literally connecting the entire globe through its fluid, shifting state — allowed me to expand the focus outside of the polar regions to our everyday experience.”

I’d like to think of these pieces as simple surrealism. Not “simplistic,” because they’re definitely not that. They’re just unbusy, delightfully so. Small waves ripple throughout every piece. The accents, natural and otherwise, manifest the surrealism. In “the vigil,” long and thin twin candles — one extinguished, the other burning — frame the craggy face of a massive, blueish glacier. The unnaturally, outlandishly large moon in “the quiet” precedes a partially bright sky, while in “the reminder,” a rückenfigur skeleton wades through the frigid shallows. There’s not a lot going on except up close. The brushstrokes nicely request your investment in them and pay huge dividends.

At Artspace111, the brushstrokes are equally masterful. A love letter to his deceased best friend and older brother, who both died from cancer recently, local legend Dennis Blagg doesn’t get all tangled up in details. His mostly large-scale pieces also bow to the almighty vibe, and that vibe emanates from the mournful, quiet Big Bend landscape at night. Incredibly natural-seeming blues and browns rule here, engendering solemnity, reverence, peace.

*****

Most of what my wife and I came across last Saturday was representational but nontraditional. Or boring. It was new and fantastical. It was art for and of the moment, when broad, loud strokes (TikTok, pulpy murder mysteries, sci-fi, rap/metal/bro-country, sloganeering presidential candidates) and IP drive the culture at large. The content may not always be serious, or heavy, or academic, but you cannot deny its form — the sweat equity muscles its way off the canvases, a rhinestoned pro wrestler breaking through a drippy Jackson Pollock beneath a disco ball as big as Jupiter.

Is this worth complaining about, this lack of seriousness? To the old-heads, who live to whine, probably. To those of us alive now, in this fucked-up world, no matter our age, I can’t imagine how.

Or why, and “why” only leads to more questions. I asked myself “why?” a lot Saturday. “Why this reference?” “Why this subject matter?” “Why this color?” And the first answer to come to me was, “Because we’re all a little crazy.”

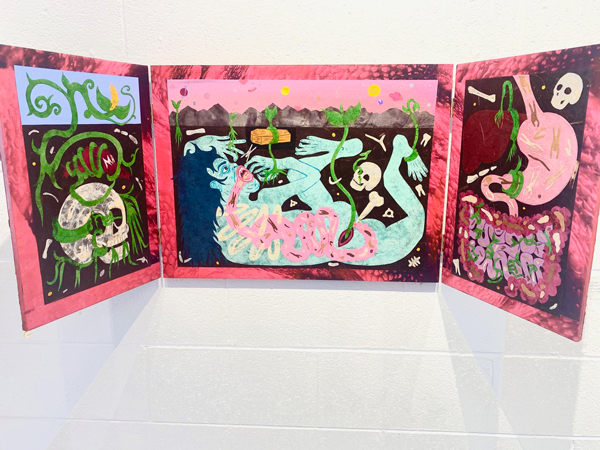

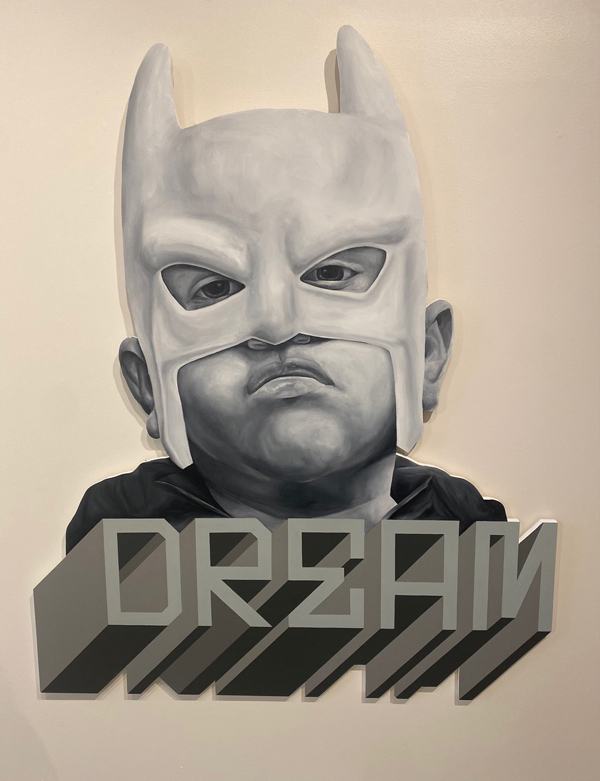

Artists and viewers alike. I’m still thinking about the pair of red-toenailed female feet traipsing through Franceska Alvarado’s “Is the Grass Really Greener on the Other Side?,” through the green grass, yes, and also past … a flower with what looks like a set of human eyes? Also taking in Carlos Donjuan’s bold, logo-like paintings and Jaylen Pigford’s cartoons gone wild, I couldn’t help but think that we are all a little cray and that the lockdown and living on the edge of democracy have only amped up our abject nuttiness. At Fort Works Art, one of Julia Curran’s two spooky hanging sculptures, the wonderfully titled “Momento Mori Evil Men (One Day You Too Will Die, Then She Will Eat You and Shit Out Your Bones),” manages a tightrope between purely scatological and almost primitively beautiful — a supine serpentine she-demon underground simultaneously gorges on tiny silhouettes while excreting skulls and femurs. Whatever your gender, Curran is clearly the kind of people you want around you.

I don’t know where she’s from or where most of the other exhibiting artists call home, and I’m not going to Google them because A.) who has time for that? and B.) when we really think about it, the fact that they’re showing in Fort Worth makes them local enough to discuss in this hyper-local rag and among you hyper-local people. Of the names I recognized last Saturday during Fall Gallery Night, most of them delivered refined traditionalism, art for us, essentially. Everyone else, the purveyors of art for artists, gave me hope. Maybe there’s more to this 11th-most populous American city with the annoying smalltown attitude than we thought.

Photo by Anthony Mariani

Photo by Anthony Mariani