On July 29 114 years ago, a white-hot rage seized a large number of folks of the Caucasian persuasion in East Texas. It didn’t take much.

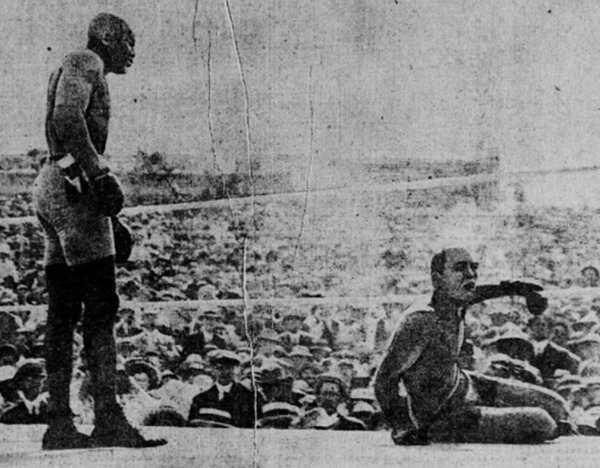

A few weeks earlier, Galveston native Jack Johnson, a descendant of American slaves, had crushed Great White Hope Jim Jeffries in “The Fight of the Century.” Black folks around the country were walking with a little more steam in their stride and probably even feeling a little pride, but many whites called it uppity behavior. In East Texas, they considered it a lynching offense.

Also problematic was Black progress in the region. American slaves and their descendants were working hard and making their way. They had property and began establishing their own businesses. They were embarking on something folks used to call the American Dream. Their enslavement was over, and they thought they might be able to carve out their own piece of it.

Many of their white neighbors weren’t having it.

On July 29, 1910, mobs of white men descended on southeastern Anderson County and northeastern Houston County and began killing Black Texans (especially Black men) on sight. Anderson County Sheriff William Black dubbed it a “potshot” occasion and claimed that there were so many Black bodies lying around that the buzzards would get to most of them first. The Abilene News Reporter expressed it in the standard white vernacular of the day, simply commenting in a front-page blurb that “Whites Gathered Arms and Went Coon Hunting.”

By the morning of August 1, 1910, hundreds of Black Texans were missing or dead, but the authorities had recovered only eight bodies. A group of Texas Rangers and state militia arrived to stop the bloodshed, but the white murderers were already covering their tracks. An untold number of Black victims had been dumped in mass graves. Many members of the white mobs fled to escape prosecution. A local judge tried to prosecute some of the known perpetrators, but his efforts went nowhere.

Most of the surviving Blacks left the area, and the remaining white population “acquired” their lands and possessions. Then, the story of the entire pogrom — which came to be known as the Slocum Massacre — was erased from local memory and never addressed in Lone Star textbooks.

Courtesy of Public Domain

*****

I stumbled onto this forgotten chapter in Texas history in early 2013. I was shocked and appalled. I knew about the Tulsa Race Massacre in Oklahoma and the Rosewood Massacre in Florida. I never imagined anything like that had ever happened here. It stung me and stayed with me.

In February 2013, I wrote a feature story about the Slocum Massacre for the Austin American-Statesman. Many folks were as shocked as I was. A descendant of one of the perpetrators of the 1910 bloodshed reached out and explained how much it had haunted him and his family. Descendants of victims of the Rosewood Massacre read my article and contacted me, asking if I was interested in writing about the Rosewood incident. It was a lot to take in.

Then, I was contacted by The History Press. The commissioning editor had seen the feature I’d written in the Statesman and approached me about a book on the subject. It was another shock. I wasn’t sure I was capable of writing a book, and I know I wasn’t ready. I countered with a multi-subject title on “Texas curiosities” that would include a chapter on the Slocum Massacre, agreeing to write a single-subject title on Slocum afterward.

I didn’t exactly know what I was doing or what it would mean. And I wondered if I wouldn’t fall flat on my face, but a combination of naivete, general cluelessness, and surprising gall kept me oblivious to the possibility. I wasn’t sure I was the right person to tell the story, but I knew it needed to be told. I just went to work.

The “Texas curiosities” book became Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional and Nefarious, and it was published on October 29, 2013. And since I didn’t know any better, I was working on the Slocum Massacre at the same time. The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas wound up being published seven and a half months later.

I’ve published several books since but none as disturbing as the one on the Slocum Massacre, and if it weren’t for cooler heads (not mine), the book might have not been published at all.

*****

Courtesy The History Press.

Last year, as I was collecting email correspondence and interviews for the E.R. Bills Collection at TCU (now part of the Archives and Special Collections of the Mary Couts Burnett Library), I was surprised by what that mixture of naivete, general cluelessness, and surprising gall had led to. A writer becoming an author. A journalist coming to be called a historian. Neither almost-imperceptible shift had occurred to me during my research or collation of information regarding the subject matter. They just happened along the way.

It’s particularly evident in The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas. And though in the intervening decade it had slipped my mind, my relationship with my publisher had been quite contentious, and my commissioning editor and I went back and forth for months on what would become the title of the book. I was surprised I didn’t remember.

On September 10, 2013, my commissioning editor informed me that the publisher had decided that the title would be The 1910 Slocum Massacre in East Texas. I agreed, initially, but was privately noncommittal. I was still just doing the work. But in an email sent at noon on November 14, 2013 — after a few phone conversations with my commissioning editor — I officially stated, “I’d like the title revisited. I have uncovered 2-3 times as much material as I had for my original article, and things just get worse and worse. In my opinion, the title should be something like: East Texas Genocide: Uncovering the Slocum Massacre.”

Forty-six minutes later, my commissioning editor responded cordially and pragmatically. “I don’t think they’ll go for something as strong as ‘genocide’ in the main, but I’ll talk it over with them.”

Thirteen minutes afterward, I suggested “The Slocum Massacre: A Genocide in East Texas.”

Today, I marvel at my impudence if not outright impertinence. My first book wasn’t even out yet, and I was already under contract for the Slocum Massacre book. Who exactly did I think I was?

No one, in particular, I assure you.

In fact, when I look back, now, I’m not sure it was me at all. It was simply stumbling onto the shocking narrative itself. The facts. An honest appraisal of the information on hand.

Courtesy E.R. Bills

The truth demanded acknowledgment.

Yes, I was a cub scout about it.

Yes, my naïve stance on the issue probably didn’t serve my personal prospects or my publisher’s bottom line very well, but it wasn’t a fluffy human-interest piece. It was the story of an atrocity. I believed the narrative dictated the branding.

A large number of Black Americans — Black Texans — had been let down by their country and their state. And I felt a compromise on the title of the book would be a betrayal of what they’d endured. And though I didn’t have the experience, the standing, or the contractual edge to mount any serious challenge to the final decision, I became, in retrospect, wildly contrarian. On November 27, 2013, I was anxious and maybe even mildly combative. “Have we got word on the title change yet? Still looking at The Slocum Massacre: A Genocide in East Texas. And the completed chapters already established that it was clearly genocide.”

I didn’t get a response until December 3, 2013. My commissioning editor informed me they’d emailed the publisher about it and when they heard something, they would let me know.

I can’t remember now if I was fit to be tied or if I simply stewed, but I was definitely the former when I finally received a response from my editor on January 2, 2014:

I think we covered everything that needs to happen at this juncture: Complete the attached image list and send it back to me, and I’ll see what I can do.

I’ll talk to the publisher about pushing your deadline a month, but I can’t make any guarantees.

The final title was decided a while back: The 1910 Slocum Massacre in East Texas. I would like to try and not change this right now, since it seems the project is taking its final shape. I do think this title will work, and its direct nature seems to help imply the severity of the subject matter.

I responded a little over an hour later:

We don’t have to change the title right now, but I don’t like it, and I’ve expressed this. There’s no reason to include “1910” in the title because there wasn’t a massacre [in Slocum, Texas] in 1911, 1920, etc. When the Rosewood Massacre is discussed, it is not as the 1923 Rosewood Massacre. Same with the Tulsa Riots. These are singular events that only happened once. And throwing “of East Texas” in just makes it clunky. The Slocum Massacre should be mentioned in the same breath as the Rosewood Massacre or Tulsa Riots [which we now rightfully refer to as the Tulsa Race Massacre], not parsed and stamped with a date. And my book may make it such/so, especially if it’s marketed right. The impulse to shrink down for an especially localized audience is not right for this book, an effort that will be definitive and controversial. … Isn’t the obvious prudent thing to do is postpone the deadline for 30 days? Is the [publisher] more concerned with getting A story or THE story? Again, I’m working on a definitive book.

I did throw in an “apologies for any headaches I cause,” but my impertinence was now bordering on arrogance.

Happily, I was informed that Texas Obscurities, which been on the shelves for only two months, had already sold 1,300 copies — which I didn’t think was too shabby, especially for a debut thrown together in a matter of months.

Thankfully, my commissioning editor tolerated my obstinance and responded 16 minutes later:

For the title: I understand your concerns and will bring them to the publisher. However, I will need some viable replacements. What are you thinking would be better? I have some ideas, but I would like to know what you are thinking first.

I wanted to wait [until] after [January 1] because I did not want to push the project without a concrete idea of when it would be able to be submitted, because otherwise it risks getting continuously pushed in the production schedule. We of course want The story and not just A story, but concrete dates are still needed when rescheduling a project to ensure that it will be given the attention it deserves.

At 8:50 a.m. on January 8, 2014, I, perhaps ill-advisedly, reiterated my stance:

Thought about it and thought about it — researched it. At the time, the Slocum Massacre was called a “Race War.” Except it turned out to be one-sided. It wasn’t simply a killing spree or a collection of homicides. It was a premeditated attempt to kill all the Black people in the Slocum area. It was a genocidal rampage. I know we don’t like the term “genocide.” Or “genocidal.” But that’s what it was: genocidal. And no better word fits. There’s just no way to get around what it really was. It was genocidal. And it was a rampage. So, I think the title should be: The Slocum Massacre: A Genocidal Rampage in East Texas.

Ever tactful, my commissioning editor continued to tolerate my growing and arguably outrageous intractability, getting back with me by 9:44 a.m.:

I’ll see what they say about this, and I’ll include your note on the history. If they think the language is too charged, however, I think a version of this description you have just given me could make a really great component to the cover copy: that way, we get the message out and we are accurate, but are able to appease the cautious side of the publisher. I think that may be the best-case scenario (and perhaps even better — since you are directly justifying the claim as opposed to just stating it as a title) if they do not want to have “genocide” in the title.

Inappreciative and unbowed, I wrote, “OK, but if they flag this, I’d prefer to just go with: The Slocum Massacre,” adding:

But I must say, if we’re looking to avoid controversy or language that is too charged in regards to the title, advertising, reception, etc., there’s no way of marketing this book right. It explores a heinous injustice and indicates willful, arguable criminal negligence on the part of the state and elements in Anderson County. When published, if it doesn’t lead to digs and excavations looking for dozens of bodies and reparations aren’t at least discussed, we didn’t do our job.

At 2:45 p.m. on January 29, 2014 (three weeks later!!!), my editor — whom I truly believe fought the good fight — sent me a short communique: “They want to go with The 1910 Slocum Race Massacre in East Texas. I know your reservations about the time period in the title, but it is something we feel strongly about and will make sure it doesn’t get too cluttered on the cover, which I know is a concern of yours.”

Extreme chutzpah and my cub scout tenacity took over. I stewed and then composed an ultimatum:

That’s not going to work. I don’t and won’t make enough money off this book to put up with much.

No offense, but perhaps [the publisher] and E.R. Bills should part ways on this particular project. I’ll contract for a second Texas Obscurities … [but] I think my Slocum Massacre efforts would be better served by a different publisher.

Less than one hour later, I doubled down: “I would like the title to be The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas. Thanks for your patience. Apologies for my lack thereof.”

Fortunately, dumb luck or cooler heads prevailed.

Photo courtesy of E.R. Bills.

We didn’t extend the deadline, but my final title suggestion stuck.

In the end, I was headstrong to a fault — but deadpan correct about the subject matter. More importantly, the publisher put up with my asininity and produced a title of remarkable note, making the Slocum Massacre part of the national conversation on race. And this was before Black Lives Matter, Critical Race Theory, DEI, and every other manufactured right-wing bogeyman.

The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas — the publication of which lay in question until just three and a half months before its release — went on to sell tens of thousands of copies and galvanized efforts for the first Texas state historical marker specifically acknowledging racial violence against African Americans. And I was honored to work on this monument, the Slocum Massacre marker, with Constance Hollie-Jawaid, a descendant of Slocum Massacre victims and the chief spokesperson for the cause. The book itself was later optioned for feature-film treatment, and Hollie-Jawaid and I co-wrote a screenplay (which was also optioned), but it was never produced.

*****

Photo courtesy of Paul Beatty.

A mistake often cited in journalism since forever and today is to “bury the lede.” And burying the lede is often a rookie faux pas. To me, removing the term “genocide” from the title of my second book would have been akin to burying the lede. After what I’d learned about the Slocum Massacre, I couldn’t in good conscience remove it. I didn’t care about the consequences in terms of profit margin or general marketability. I wanted to do what was right. I was impractical, in some ways incorrigible, and my contrarianism approached belligerence. Now, I’m just thankful my publisher and commissioning editor put up with me. And thrilled with the minor coup we were able to pull off.

But, here, I have to come clean. I made a rookie mistake in this piece.

I buried the lede.

Yes, the back and forth that led to the publication of my book on the Slocum Massacre is interesting. And so is the 10-year anniversary of that publication. But the Slocum Massacre marker effort that followed the publication was grueling, and, once the marker was placed, Texas folks went back to forgetting.

This profoundly demonstrates what a cub scout I was on January 9, 2014, when I suggested that when the book was published “if it doesn’t lead to digs and excavations looking for dozens of bodies and reparations aren’t at least discussed, we didn’t do our job.”

We didn’t do our job.

Yes, I’m proud of the book. Yes, I’m proud of the historical marker. And, yes, I’m honored to have my papers and research on the Slocum Massacre housed in a collection bearing my name at TCU’s Mary Couts Burnett Library. But dozens of Black Texans are still piled on top of one another like animals in unmarked mass graves in East Texas. Let me repeat: Dozens of Black Texans are still piled on top of one another like animals in unmarked mass graves in East Texas.

The is why my book on the Slocum Massacre is still so disturbing to me.

The mass graves lay ignored. The final truth remains buried.

The state of Florida (under a Bush — Jeb, no less) had enough conscience to get something done. The state of Oklahoma had enough decency and dignity to get something done. Why can’t we?

So, here I have to quote the last two paragraphs of the book that I gave my publisher serious grief about the title of:

This outrage should be shameful to all Texans.

The atrocities committed in the Slocum area in 1910 should give us all pause and spur commitments to definitely establish the truth, fully acknowledge it, and honestly and constructively address it.

We are less as a state and a people until we do.

We are less as a state and a people until we do.

Fort Worth native E.R. Bills is also the author of Tell-Tale Texas: Investigations in Infamous History and Texas Oblivion: Mysterious Disappearances, Escapes and Cover-Ups.

Any future attempts being made to make a movie? Screenplay? Anything ? This story needs to be told!